- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

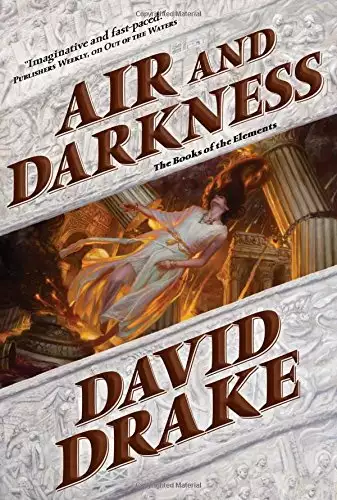

Air and Darkness, an intriguing and fantastic adventure, is both an independent novel and the gripping conclusion of the Books of the Elements, a four-volume set of fantasies set in Carce, an analog of ancient Rome by David Drake.

Here the stakes are raised from the previous novels in an ultimate conflict between the forces of logic and reason and the forces of magic and the supernatural. During the extraordinary time in which this story is set, the supernatural is dominant. The story is an immensely complex journey of adventure through real and magical places.

Corylus, a soldier, emerges as one of the most compelling heroic figures in contemporary fantasy. Battling magicians, spirits, gods, and forces from supernatural realities, Corylus and his companions from the family of the nobleman Saxa-especially Saxa's impressive wife Hedia, and his friend (and Saxa's son) Varus-must face constant deadly and soul-destroying dangers, climaxing in a final battle not between good and evil but in defense of logic and reality.

At the Publisher's request, this title is being sold without Digital Rights Management Software (DRM) applied.

Release date: November 3, 2015

Publisher: Tom Doherty Associates

Print pages: 336

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Air and Darkness

David Drake

“Help us, Mother Matuta,” chanted Hedia as she danced sunwise in a circle with eleven women of the district. The priest Doclianus stood beside the altar in the center. It was of black local stones, crudely squared and laid without mortar—what you’d expect, forty miles from Carce and in the middle of nowhere.

“Help us, bringer of brightness! Help us, bringer of warmth!”

Hedia sniffed. Though the pre-dawn sky was light, it certainly hadn’t brought warmth.

The dance required that she turn around as she circled. Her long tunic was cinched up to free her legs, and she was barefoot.

She felt like a complete and utter fool. The way the woman immediately following in the circle—the wife of an estate manager—kept stepping on her with feet as horny as horse hooves tipped Hedia’s embarrassment very close to fury.

“Let no harm or danger, Mother, menace our people!”

The things I do to be a good mother, Hedia thought. Not that she’d had any children herself—she had much better uses for her body than to ruin it with childbirth!—but her current husband, Gaius Alphenus Saxa, had a seventeen-year-old son, Gaius Alphenus Varus, and a daughter, Alphena, a year younger.

A daughter that age would have been a trial for any mother, let alone a stepmother of twenty-three like Hedia. Alphena was a tomboy who had been allowed to dictate to the rest of the household until Saxa married his young third wife.

Nobody dictated to Hedia, and certainly not a slip of a girl who liked to dress up in gladiator’s armor and whack at a post with a weighted sword. There had been some heated exchanges between mother and daughter before Alphena learned that she wasn’t going to win by screaming threats anymore. Hedia was just as willing as her daughter to have a scene, and she’d been threatened too often by furious male lovers to worry about a girl with a taste for drama.

“Be satisfied with us, Mother of Brightness!” Hedia chanted, and the stupid cow stepped on her foot again.

A sudden memory flashed before Hedia and dissolved her anger so thoroughly that she would have burst out laughing if she hadn’t caught herself. Laughter would have disrupted the ceremony as badly as if she had turned and slapped her clumsy neighbor.

I’ve been in similar circumstances while wearing a lot less, Hedia thought. But I’d been drinking and the men were drunk, so until the next morning none of us really noticed how many bruises we were accumulating.

Hedia wasn’t sure that she’d do it all again; the three years since that party hadn’t turned her into a Vestal Virgin, but she’d learned discrimination. Still, she was very glad for the memory on this chill June morning.

“Help us, Mother Matuta! Help us! Help us!”

After the third “Help us,” Hedia faced the altar and jumped in the air as the priest had told her to do. The other dancers carried out some variation of that. Some jumped sooner, some leaped forward instead of remaining in place as they were supposed to, and the estate manager’s wife outdid herself by tripping and pitching headfirst toward the altar.

It would serve her right if she knocked her few brains out! Hedia thought; but that wasn’t true. Being clumsy and stupid wasn’t really worthy of execution. Not quite.

The flutist who had been blowing time for the dance on a double pipe halted. He bowed to the crowd as though he were performing in the theater, as he generally did. Normally the timekeeper would have been a rustic clapping sticks together or perhaps blowing a panpipe. Hedia had hired Daphnis, the current toast of Carce, for the task.

Daphnis had agreed to perform because Hedia was the wife of a senator and the current Governor of Lusitania—where his duties were being carried out by a competent administrator who needed the money and didn’t mind traveling to the Atlantic edge of Iberia. Saxa, though one of the richest men in the Republic, was completely disinterested in the power his wealth might have given him. His wife, however, had a reputation for expecting people to do as she asked and for punishing those who chose to do otherwise.

The priest Doclianus, a former slave, dropped a pinch of frankincense into the fire on the altar. “Accept this gift from Lady Hedia and your other worshipers, Mother Matuta,” he said, speaking clearly but with a Celtic accent. “Bless us and our crops for the coming year.”

“Bless us, Mother!” the crowd mumbled, closing the ceremony.

Hedia let out her breath. Syra, her chief maid, ran to her ahead of a pair of male servants holding their mistress’ shoes. “Lean on me, Your Ladyship!” Syra said, stepping close. Hedia put an arm around her shoulders and lifted one foot at a time.

The men wiped Hedia’s feet with silken cloths before slipping the shoes on expertly. They were body servants brought to Polymartium for this purpose, not the sturdier men who escorted Lady Hedia through the streets of Carce as well as outside the city, lest any common person touch her.

The whole purpose of Hedia’s present visit to the country was to demonstrate that she was part of the ancient rustic religion of Carce. The things I do as a mother’s duty! she repeated silently.

Varus joined her, slipping his bronze stylus away into its loop on the notebook of waxed boards on which he had been jotting notes. He seemed an ordinary young man, handsome enough—Hedia always noticed a man’s looks—not an athlete, but not soft, either. A glance didn’t suggest how extremely learned Varus was despite his youth, nor that he was extremely intelligent.

“The reference to me,” Hedia said, “wasn’t part of the ceremony as Doclianus had explained it. I suppose he added it on the spur of the moment.”

“I’ve already made a note of the usage,” Varus said, tapping his notebook in acknowledgment. “From my reading, it appears that a blood sacrifice—a pigeon or a kid—would have been made in former times, but of course imported incense would have been impossibly expensive for rural districts like this. I don’t think the form of the offering matters in a rite of this sort, do you? As it might if the ceremony was for Mars as god of war.”

“I’ll bow to your expertise,” Hedia said drily. There were scholars who were qualified to discuss questions of that sort with Varus—his teacher, Pandareus of Athens, and his friend, Publius Corylus, among them; but as best Hedia could see, even they seemed to defer to her son when he spoke on a subject he had studied.

When she married Saxa, Hedia had expected trouble with the daughter. It was a surprise that both the children’s mother and Saxa’s second wife, the mother’s sister, had ignored their responsibilities so completely—letting a noblewoman play at being a gladiator!—but it was nothing Hedia couldn’t handle.

Varus, however, had been completely outside Hedia’s experience. The boy wasn’t a drunk, a rake, or a mincing aesthete as so many of his age and station were. Hedia’s first husband, Gaius Calpurnius Latus, had been all three of those things and a nasty piece of work besides.

Whereas Varus was a philosopher, a pleasant enough fellow who preferred books to people. That was almost as unseemly for the son of a wealthy senator as Alphena’s sword fighting was. Philosophy tended to make people question the legitimacy of the government. The Emperor, who was that government, had every intention of dying in bed, because all those who had questioned his right to rule had been executed in prison.

Even worse, Varus had set his heart on becoming a great poet. Hedia was no judge of poetry—Homer and Vergil were simply names to her—but Varus himself was a very good judge, and he had embarrassed himself horribly with the disaster of his own public reading. Indeed, Hedia would have been worried that embarrassment might have led to suicide—Varus was a very serious youth—had not a magic disrupted the reading and the world itself.

In the aftermath, Varus had given up composing poetry and was instead compiling information on the ancient religion of Carce, an equally pointless exercise, in Hedia’s mind, but one he appeared to have a talent for. This shrine was on the land from which the Hedia family had sprung, and they had been the ceremony’s patron for centuries. Her only personal acquaintance with the rite had come when an aunt had brought her here as an eight-year-old.

Hedia had volunteered to bring Varus to the ceremony from a sense of duty. His enthusiastic thanks had shown her that she had done the right thing. Doing your duty was always the right thing.

“Oh, Your Ladyship!” cried a stocky woman rushing toward them. Minimus, a big Galatian in Hedia’s escort, moved to block her, but the woman evaded him by throwing herself prostrate at Hedia’s feet. “It was such an honor to dance with you. You dance like a butterfly, like gossamer in the sunshine!”

Light dawned: the estate manager’s wife. The heavy-footed cow.

“Arise, my good woman,” Hedia said, sounding as though she meant it. She had learned sincerity by telling men what wonderful lovers they were. “It was a pleasure for me to join my sisters here in Polymartium in greeting the goddess on her feast day.”

The matron rose, red faced and puffing with emotion. She moved with a sort of animal grace that no one would have guessed she had from her awkward trampling as she danced in the company of a noblewoman.

“Thank you, Your Ladyship,” she wheezed. “I could die now, I’m so happy!”

Hedia nodded graciously and turned to Varus, putting her back to the local woman without being directly insulting. Minimus ushered the local out of the way with at least an attempt to be polite.

“Did you get what you needed, my son?” Hedia asked. If he hasn’t, I’ve bruised my feet for nothing, she thought bitterly. Heels and insteps both, thanks to the matron.

“This was wonderful, Mother!” Varus said with the sort of enthusiasm he’d never directed toward her in the past. She’d seen him transfigured like this in the past, but that was when he was discussing some oddity of literature or history with his teacher or Corylus. “Do you know anything about the group on the other side of the altar? They’re from India, I believe, or some of them are. Are they part of the ceremony usually?”

How on earth would I know? Hedia thought, but aloud she said, “Not that I remember from when I was eight, dear boy, but I’ll ask.”

She turned to the understeward who was in charge of her personal servants—as opposed to the toughs of her escort. “Manetho,” she said. “A word, please. Who are the people at the lower end of the swale from us? Some of them look foreign.”

“Those are a delegation from Govinda, a king in India,” said Manetho. “They’re accompanied by members of the household of Senator Sentius, who is a guest-friend of their master. The senator has interests in fabrics shipped from Barygaza.”

Manetho was Egyptian by birth and familiar with the Indian cargoes that came up the Red Sea and down the Nile to be shipped to Carce. A less sophisticated servant might have called Govinda “the King of India,” which was one of the reasons Hedia generally chose Manetho to manage her entourage when she went outside the city.

She cared nothing about politics or power for their own sakes, but the wife of a wealthy senator had to be familiar with the political currents running beneath the surface of the Republic. That was particularly true of the wife of the unworldly Gaius Alphenus Saxa, who was so innocent that he might easily do or say something that an ordinary citizen would see as rankest treason.

The Emperor was notoriously more suspicious than an ordinary citizen.

“What are they doing here, Manetho?” Varus said. He added in a hopeful tone, “Are they scholars studying our religion? I know very little about Indian religion, and I’d be delighted to trade information with them.”

Manetho cleared his throat. “I believe they’re priests, Your Lordship,” he said. “The old one and the woman, that is; the others are officials. They’re here to plant a vine.”

Hedia followed the understeward’s eyes. Two dark-skinned men with bronze spades had begun digging a hole near the base of an ilex oak; in a basket beside them waited a vine shoot that was already beginning to leaf out. The men wore cotton tunics, but their red silk sashes marked them as something more than mere menials.

Hedia thought of Corylus, who had considerable skill in gardening. He was the son of Publius Cispius, a soldier who served twenty-five years on the Rhine and Danube. That service had gained Cispius a knighthood and enough wealth to buy a perfume factory on the Bay of Puteoli on retirement.

Nothing in that background suggested that his son would be anything more than a knuckle-dragging brute who drank, knocked around prostitutes, and gravitated to a junior command on the frontiers similar to that of his father. In fact, Corylus—Publius Cispius Corylus, in full—was scholar enough to gain Varus’ respect and was handsome enough to attract the attention of any woman.

Furthermore, Corylus demonstrated good judgment. One way in which he had shown that good judgment was—Hedia smiled ruefully—by politely ignoring the pointed invitations to make much closer acquaintance of his friend’s attractive stepmother.

“Do you suppose they’d mind if I talked to them?” Varus said, his eyes on the Indian delegation. The priests—the old man and the woman—oversaw the work, while the remaining Indians remained at a distance, looking uneasy.

The woman’s tunic was brilliantly white with no adornment. Hedia wondered about the fabric. It didn’t have the sheen of silk and, though opaque, it moved as freely as gossamer.

“If them barbs bloody mind,” said Minimus, “I guess there’s a few of us here who’ll sort them out about how to be polite to a noble of Carce.”

“I scarcely think that will be necessary, Minimus,” Hedia said, trying to hide her smile. “A courteous question should bring a courteous response.”

Minimus had been brought to Carce as a slave five years ago. His Latin was bad and even his Greek had a thick Asian accent. For all that, he thought of himself as a member of Senator Saxa’s household and therefore the superior of anybody who was not a member. Freeborn citizens of Carce were included in Minimus’ list of inferiors, though he understood his duty well enough to conceal his feelings from Saxa’s friends and hangers-on.

Varus wandered away, also smiling. He was an easygoing young man, quite different from his sister in that respect. When Hedia arrived in the household, it had seemed to her that Varus’ servants were taking advantage of his good nature. Before she decided to take a hand in the business, Varus had solved the problem in his own way: by suggesting that particularly lax or insolent members of his staff might do better in Alphena’s section of the household.

Doclianus had waited until Hedia had finished talking with her son, but he came over now and bowed deeply. For a moment she even wondered if the priest was going to abase himself as the heavy-footed matron had done, but he straightened again. The bow was apparently what a Gaul from the Po Valley thought was the respect due to his noble patron.

“Allow me to thank you on behalf of the goddess, Your Ladyship,” Doclianus said. “I hope everything met with your approval?”

There were a number of possible responses to that, but Hedia had come to please her son and Varus was clearly pleased. “Yes, my good man,” Hedia said. “You can expect a suitable recognition when my gracious husband distributes gifts to his clients during the Saturnalia festival.”

The priest didn’t look quite as pleased as he might have done; he had probably been hoping for a tip sooner than the end of the year. Hedia was confident that her earlier grant of expenses for this year’s festival had more than defrayed the special preparations, including the cost of frankincense. Hedia wasn’t cheap, and her husband could easily have afforded to keep an army in the field; but neither was she willing to be taken for a fool.

“Who are the Indians?” Hedia said, changing the subject. She was willing to be as direct as necessary if the priest insisted on discussing fees, but she preferred to avoid unpleasantness. Hedia was not cruel, though she knew that those who observed her ruthlessness often mistook it for cruelty.

“Oh, I hope that’s not a problem, Your Ladyship,” said Doclianus, following her eyes. “Senator Sentius requested that a delegation from the King of India—”

Hedia’s lips quirked.

“—be permitted to offer to Mother Matuta a shoot of the grapevine which sprang up where the god Bacchus first set foot on Indian soil during his conquest of the region.”

He cleared his throat and added, “Perhaps your husband knows Sentius?”

“Perhaps he does,” Hedia said, her tone too neutral to be taken for agreement. “I don’t see why the Mother should be particularly connected with grapes, though.”

In fact, Hedia recalled that Sentius had visited Saxa recently to look over his collections. That was the sort of thing that took place frequently and gave her husband a great deal of harmless pleasure.

With the best will in the world, Hedia herself had to fight to keep from yawning when Saxa showed her the latest treasure that some charlatan had convinced him to buy. He owned the Sword of Agamemnon, the cup from which Camillus drank before he went to greet the senators announcing his appointment as dictator, and Hedia couldn’t remember what other trash.

That was unfair. Some of the objects were probably real, though that didn’t make them any more interesting to her.

“That puzzled me also,” Doclianus said. “The man in blue, Arpat—”

A man of forty or so. Arpat wore a curved sword, but its jeweled sheath and hilt looked more for show than for use.

“—told me that according to their priests, these woods have great spiritual power, and Mother Matuta, as goddess of the dawn, links them with the East.”

Hedia nodded. For the first time Doclianus spoke in a natural tone without the archness that had made his voice so irritating. The priest had obviously been trying to seem cultured to his noble patron, but he didn’t know what culture meant in Hedia’s terms.

“I see,” she said. “Well, I’ll wait here and meditate until my son returns from his discussions.”

Varus was having an animated conversation with the priest in the ragged tunic. Hedia wondered what language they were speaking in. It wouldn’t have amazed her if Varus spoke Indian—his erudition was remarkable—but it seemed more likely that the Indians knew Greek.

Doclianus accepted his dismissal without showing disappointment. Hedia watched him returning to the cluster of women who had taken part in the ceremony. There were a hundred or so local spectators besides. Hedia wondered if they had come to see the nobles from Carce.

She considered the ceremony. Though Hedia observed the customary forms, she didn’t believe—and never had believed—in gods. On the other hand, she hadn’t believed in demons or magic, either, but she had recently seen ample proof that both were real. And beyond that—

Varus and the Indian priest were examining the successfully planted vine.

My son is a great scholar, Hedia mused. I’ve never had much to do with scholars.

But Varus had shown himself to be a great magician also, and that was even more surprising.

* * *

“GOOD HEALTH TO YOU, Master Corylus!” called the woman at the counter of the bronze goods shop. “When you have a moment, I’d like to show you a drinking horn that we got in trade.”

“Not today, Blaesa,” Corylus said, forcing a smile for her. He was tense, but not too tense for courtesy. “I’ll try to drop by soon, though.”

The smith himself in the back of the shop was Syrian, but Blaesa, his wife, was an Allobrogian Gaul from close to where Corylus had been born. She liked to chatter with him in her birth tongue, and an occasional reminder of childhood was a pleasure to Corylus also.

He and Marcus Pulto, his servant, had come down this narrow street scores of times to visit the Saxa town house. They were as much part of the neighborhood as the merchants who rented space on the ground floor of the wealthy residences.

Pulto exchanged nods with the retired gladiator who was working as doorman of the jewelry shop across the way. Although the mutual acknowledgment was friendly enough, Corylus knew that at the back of his mind each man was considering how to take the other if push came to shove. That didn’t mean there was going to be a problem: it was just the way men of a certain type related to each other.

Corylus’ father was the third son of a farmer. He had joined the army and had risen through a combination of skill, courage, and intelligence to become the leading centurion of a legion on the Rhine: the 5th Alaudae. After twenty years’ service, Cispius was promoted again, becoming tribune in command of a squadron of Batavian cavalry on the Danube; he was made a Knight of Carce when he retired.

The other factor in Cispius’ success in the army was luck: all the intelligence and skill in the world couldn’t always keep a soldier alive, and courage was a negative survival factor. Choosing Pulto as his servant and bodyguard might have been the luckiest choice Cispius had made in his military career.

Cispius had led his troops from the front. Pulto was always there, anticipating dangers and putting himself between them and the Old Man. On one memorable afternoon Pulto had thrown himself over his master, unconscious on the frozen Danube, while Sarmatians thrust lances at him.

When Corylus went to Carce to finish his education with the finest rhetoric teachers in the empire, Cispius had sent Pulto with him. The dangers of a large city are less predictable than those of the frontier, and in many ways they are greater for a young man who has grown up in the structure of military service. Pulto would look out for the Young Master, just as he had for the father.

Corylus hadn’t thought he needed a minder, and perhaps he hadn’t: he was an active young man who avoided giving offense but who could take care of himself if he had to. In the army, though, you were never really alone, even when you were—unofficially—on the east side of the Danube with the Batavian Scouts.

Early in his classes with Pandareus of Athens, Corylus had intervened when Piso, a senator’s son, and several cronies had started bullying a youth who was both smaller and obviously smarter. Corylus could have handled Piso and his friends easily enough, but he hadn’t thought about the retinue of servants accompanying the bullies.

The servants hadn’t gotten involved, because Pulto stood between them and the trouble with his hand lifted just enough to show the hilt of the sword he wore under his tunic. The weapon was completely illegal within the boundaries of Carce, but nobody made a fuss about it, since the youth being bullied was the son of Senator Gaius Alphenus Saxa. Saxa’s influence couldn’t have saved his son from a beating, but it had been more than sufficient to prevent retribution on those who had stopped the beating.

Varus had been appreciative. He had as few friends in Carce as Corylus did, though in Varus’ case that was because he didn’t have any use for hangers-on or any interest in the drunken parties that were the usual pastime for youths of his class. Corylus was scholar enough to discuss the literature and history that mattered to Varus; and because Varus gave his new friend use of the gymnasium that was part of the Alphenus town house, Varus started exercising also.

The sauce on the mullet was that the household’s private trainer, a veteran named Marcus Lenatus, was a friend of Pulto from when they both served with the Alaudae. Quite apart from the good that exercise did Varus, Pulto had had a word with his army buddy. Varus never again left the house without an escort who were willing to mix it with three times their number of thugs, if that was what it took to keep their master from a beating. The youth himself was probably oblivious of the difference.

“I should have worn a toga,” Pulto muttered harshly. “I don’t care what you say, I should’ve worn one!”

“Absolutely not,” Corylus said firmly. “The senator won’t set eyes on you, and you’re not here to impress the staff by wearing a tent. Besides, they know who you are.”

In Corylus’ heart he wondered if Pulto might not be right, though. It was too late to change now.

The toga had been normal wear in ancient Carce, but now the heavy square of wool was worn only on formal occasions. Corylus wore a toga in class, because Pandareus was teaching them to speak in court, where it was the uniform of the day. Even when Corylus came straight from class to the town house, he doffed the toga inside before he went back to the gymnasium or upstairs with Varus to his suite of rooms.

Today Varus was with his mother forty miles north in Polymartium; Corylus had been summoned to the town house by Saxa himself. There were any number of reasons the senator might have sent for him, but none of them seemed probable and some of the possibilities were very bad indeed.

He can’t possibly think that I’ve been trifling with his daughter. Can he?

Realistically, Saxa wouldn’t be talking with Corylus about his dealings with Alphena. Saxa’s wife would have taken care of that.

Corylus thought Hedia liked and respected him; they’d been through hard places together and with Alphena as well. But if Hedia thought Corylus was jeopardizing Alphena’s chances of a proper—virgin—marriage with another noble, she would have him killed without hesitation. Once Alphena was married, she became the responsibility of her husband. Until then her purity was the duty of her parents, and Hedia took family duties very seriously.

But if not Alphena, why?

Saxa’s doorman saw them approaching and bellowed, “The honorable Publius Cispius Corylus and Marcus Pulto!”

The blond doorman still had a Suebian accent, but it wasn’t nearly as pronounced as it had been the first time he had been on duty when Corylus arrived at the town house. Besides taking elocution lessons, the doorman had learned manners and no longer treated free citizens of Carce as trash trying to blow into Saxa’s house from the street. That was particularly important when dealing with a veteran like Pulto or with the frontier-raised son of an officer.

Corylus nodded in acknowledgment, as he had seen his father do a thousand times to the guards when he entered headquarters. Nobody saluted on active service, but courtesy was proper anywhere—and courtesy toward the men you expected to follow you into battle was also plain good sense.

In the past when Corylus visited the Alphenus residence, the entrance hall had usually been crowded with Saxa’s clients and with people simply trying to cadge a favor or a handout. Today the staff had crowded the visitors into the side rooms where ordinarily servants slept. Three understewards—the fourth must be with Hedia and Varus—in embrodiered tunics stood to the left of the pool that fed rainwater from the roof into cisterns. Agrippinus, the majordomo, waited at the back of the hall at the entrance to Saxa’s office.

“Welcome, Publius Corylus!” Agrippinus said. Nothing in his accent suggested that twenty years before he had come to Carce as a slave from Central Spain. “I greet you in the name of Gaius Alphenus Saxa, Governor of Lusitania, former consul, and senator of the Republic of Carce!”

Saxa came out of the office, beaming and holding out his hands. “Thank you so much for coming, Publius Corylus,” he said. “Come into the office, if you will. I have a business on which I hope you can help me.”

Varus’ father was a pudgy man of fifty who was starting to go bald at the top of his head. He sometimes looked kindly, as he did now, or worried, or startled, and often completely dumbfounded. Saxa had never displayed harshness or anger that Corylus knew of.

“Guess we were wrong to worry,” Pulto murmured in a voice as low as he would have used at night on the east side—the German side—of the Rhine. “I’ll look Lenatus up in the gym.”

“I was honored by your summons, Your Lordship,” Corylus said, walking forward with his own hands out. “I will of course do anything I can to aid Your Lordship.”

This was even more surprising than it would have been to find the public executioner waiting for him. Better, of course, but still not a comfortable experience. Corylus had grown up in the Zone of the Frontier, where “unexpected” was too often a synonym for “fatal.”

Corylus touched Saxa’s hands, but he was too unsure of himself to grip them as he would have done with Varus under the same circumstances. What is going on?

“Well, I certainly hope so, my boy,” said Saxa, drawing Corylus into the office. Agrippinus closed the door behind them.

* * *

ALPHENA BACKED AND SIDESTEPPED LEFT as the trainer came on at a rush. Marcus Lenatus was using his weight. He kept his infantry shield advanced, a battering ram that would have knocked her over if she had waited to meet it.

Lenatus turned to keep facing her, but the weight of his heavy shield slowed him. Alphena thrus

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...