The Most Beautiful of All Possible Worlds

Don’t tell me life is short. With the benefit of my considerable experience, or should I say in spite of it, I’m still willing to buy that life is beautiful if you dress it up right, that people are basically good, or that love can save you. I still want to believe. Tell me that life is meaningful, and you’ve got my ear. Tell me that life is a journey, and I’ll nod in agreement. But try convincing me that said journey is short, and you’ve lost me; that’s one cliché I can’t abide. If you think life is short, just wait. One of these days it might not end for you; it’ll just keep going and going and you’ll see that life is not a breathless sprint to the grave, gone in a heartbeat, but an odyssey that stretches on and on into eternity. Once it starts, it never ends, not even if you want it to. I should know.

I have gone by other names: Euric, Pietro, Kiri, Amura, York, and Whiskers. Currently I answer to the name of Eugene, though the attendants here at Desert Greens call me Mr. Miles. In August, I turn 106 years old. Wow, you’ll say, what a full life! Impressive! What’s your secret? But the fact is, I’m ready to die. There is nothing holding me here. I only hope that I am not born again, for I don’t think I could endure another loveless existence.

As far as I know, I first came to live on the Iberian Peninsula in the town of Seville, or Ishbiliyah as it was then known, during the golden age of Abd al-Rahman III in al-Andalus. If you’ve read your history, you probably know something about Spain under the Moors: how it was a global seat of wisdom, a paradise for scholars and poets and artists, philosophers, historians, and musicians, how Arabic was the language of science—mathematics, astronomy, and medicine. You’ve likely heard about the wondrous architecture of the mosques with their flowing arabesques and honeycombed vaults, their domed tops echoing the hypnotic suras of the Quran. You’ve probably heard about the great walled alcazabas, and the splendor of the riads and gardens. That is where the story of Euric and Gaya begins.

Of all my lives, this has been the longest, at turns the most rewarding and the most fruitless, the most satisfying and the most trying, and, accounting for the enduring awareness and attendant weight of all my previous follies and failures, the most exhausting. So don’t tell me life is short.

But I digress.

Now I live here at Desert Greens, an eldercare facility in Lucerne Valley. I’ve been here for twelve years. It’s a nice enough place, I suppose, though there exist no actual “greens” on the premises, unless you count the blighted buffalo grass on the west end of the facility. There are a few picnic tables—four, to be exact—out there amidst the thirsty palms, which, depending on the direction you choose to face, confer views of the Ord, Granite, or San Bernardino Mountains, the craggy Ords and Granites brown most of the year. It’s a stark landscape, yes, but a beautiful one; timeless, like me.

I still get around well enough. I can go to the bathroom on my own, or walk down the corridor to the common area, or the cafeteria, or the aforementioned “greens,” where a more sociable soul than myself might find a game of dominoes, or even chess, if he were so inclined. Were it my wish to learn to paint landscapes, or achieve computer competency, I could do that, too, here at Desert Greens. But I don’t.

Though there is no denying a slight antiseptic air here at the Greens, don’t imagine it as a hospital or an institution exactly. I have my own quarters, albeit small, populated with my own things, though if eleven centuries have taught me anything it’s how to travel light. Thus, I possess comparatively little next to most of the tenants: two shelves’ worth of cherished books, from Virgil to Proust to O’Connor, and of course my dear Oscar; a few dozen history texts, ranging from the Greeks to the Romans to the Moors to the Americans; and an old Gideons Bible swiped decades before from the Oviatt Hotel in downtown Los Angeles (not by any means to be confused with the lavish Oviatt Building on Olive Street), along with a dozen jigsaw puzzles at any given time and a shoebox half-full of keepsakes, including my tags and medals from the war, a typed letter from one of my high school history students twenty years after I taught her, and the bone-handled jackknife my war buddy Johnny Brooks gave me. Then there’s my paperweight on the dresser, a walnut-sized spherical rock I found along the Oregon coast on my honeymoon with Gladys. Oh, what a beautiful wedding it was! Oh, what a lovely time we had in Cannon Beach!

Evenly spaced atop the dresser I keep three framed photographs of my beloved Gladys (or Gaya, if you will), gone these eight years. Still not a day goes by that I do not gaze at these photographs and think of her. In the first picture, a black and white portrait, Gladys is but a young woman of nineteen or twenty, many years before I’d found my way back to her. She looks at once delicate and formidable with her dark, intelligent eyes and her generous lips. She’s not smiling in the photo; rather her face is at rest for the occasion, her hands folded neatly in her lap.

In the second photograph, Gladys is in the prime of her life, 1948, flanked by her two girls, Donna and Nancy, six and eight years old respectively, the three of them clad in bathing suits and floppy sun hats, waving at the camera from Pismo Beach or some other California seaside retreat. I didn’t know Gladys then, either. Our fateful reunion was still twenty years in the future. Had I known it was coming, I might have done more with my life. If you look close enough at the photo, you’ll see that Gladys is still wearing the wedding ring from her first husband, Richard, who lost his life at Guadalcanal years before the photo was taken.

The final photograph depicts Gladys and me in midlife. It would have been the late-1970s, not long after we bought the house in Hesperia. There’s nothing particularly memorable about this instant frozen in perpetuity, no special occasion or importance attached to it. The photo was snapped by a busboy upon my request. Gladys and I are sitting at a table at King George’s Smorgasbord, wineglasses half-full, our dinner plates clean, both of us smiling, although Gladys cannot disguise a bit of a deer-in-the-headlights look, as though she wasn’t expecting the photograph. God, we were happy; for the whole of our thirty-five years together it seemed we were happy every step of the way; through every peak and valley our love abided surely and steadily. And why not? Our reunion was, after all, eleven hundred years in coming. And never once did we take it for granted.

But again, I digress.

The attendants here at Desert Greens are invariably cheerful, though most of them speak to me with that cloying condescension of the sort one might employ with a toddler or a puppy. I play along with them to some degree, though despite my vintage I am still “quite sharp,” an observation staff members share with me weekly. They are all very professional, which is to say attentive, even-tempered, if not consistently measured in their distance. While the others are fastidiously unyielding in their professionalism, which is fine by me, the one called Marguerite has been known to harmlessly flirt with me on occasion, a kindness I oblige as if it flatters me, though in truth nothing could arouse my ardor at this point, not with Gladys dead and gone. Aside from Marguerite’s occasional playful antics, the rest of the staff here at Desert Greens maintain a polite deference and patient disposition that never quite achieves warmth.

When Gladys died, there was nothing left for me to lose. Had I believed for one minute that it would’ve relieved my suffering, I would have taken my own life without question. But I knew that any such merciful conclusion was beyond my reach. Chances were, I would only be reborn one step further removed from Gladys, one more lifetime distant from Gaya.

After the memorial service, my slide into decrepitude was sudden and sweeping. It seemed I aged twenty years in a matter of weeks. The dishes piled up. The phone went unanswered. I stopped eating beyond the bare minimum, stopped bathing, and I hardly got out of bed. The mail piled up and the bills went unpaid. Neighbors’ casseroles were left untouched, until they eventually stopped coming around. Gladys’s daughters dropped by on occasion, invariably attempting to roust me out of my isolation for a meal in town or a walk in the park, but even Donna and Nancy gave up eventually. I was unreachable. A normal person would have given up the will to live and followed Gladys to her grave, but I was a preternaturally hearty physical specimen for any age, and besides, I knew that such a notion was futile. I’d been lucky enough to find my true love twice, but surely lightning would not strike thrice.

And so, I languished, holed up in my house, resigned to my isolation. To be honest, it was only the grubby state of the house, and the constant upkeep required to render it barely habitable, that finally drove me to Desert Greens.

While it is true that in my tenure here at Desert Greens I have been far from a gadabout, and for the most part a certifiable recluse, I am not unacquainted with my fellow denizens. Namely, there is Irma McCleary across the hall, who smells of wilting gardenias and the inside of pill bottles. I would put Irma’s years somewhere between eighty-five and ninety, although decorum necessitates that I never solicit a woman’s age. An interesting fact about Irma: Her hair is quite literally blue, and I don’t mean grayish blue, rather somewhere between baby blue and cornflower blue. Only recently did I discover that this fact is not owing to some unfortunate mishap involving off-brand hair dye, or an unforeseen chemical reaction, but instead to personal preference. As it turns out, Irma willfully cultivates her azure hair for reasons I’m not given to understand. Unerring in her politeness, though she’s been calling me Benson for nearly a decade now, Irma is quick with a compliment, as recently as last week commending my choice of moccasin-style slippers.

Two doors down from me resides Herman Billet. Herman is an unnaturally lean, bullet-headed old buzzard who is about as hale and hearty as a paper bag full of cobwebs. The next stiff breeze could be the end of Herman. While Herman might appear to be even more decrepit than yours truly, I have it on good authority that the man has not yet lived to see his ninetieth birthday. Mr. Billet is just a babe still, though you wouldn’t know it to see him wandering the hallways, stooped and listless, Danish crumbs ringing his slackened jaw. My exchanges with Herman have been limited mostly to assisting him in locating the commissary or helping him find his way back to his quarters from said commissary. More than once he has mistaken me for his son, and once for a former business partner, a certain Phil Jacoby, who, I’ve come to learn, died an untimely death some forty-odd years ago.

In the next corridor over resides Bud Brewster, he of the ceaseless fly-fishing adventures and intolerant politics, who calls himself a patriot and claims to have fought in the 478th Infantry Division, though no such outfit ever existed. Despite my own service, I have no interest in exposing Bud Brewster as a fraud, and even less interest in talking to him.

Across the hall from Bud Brewster resides Iris Pearlman, a charming if not overly talkative woman, who has cultivated an unimaginably large family and likes nothing more than to inform people on the particulars of their existence. To wit, there is daughter Judith in Fort Worth, a retired school administrator. Judith’s husband, Mac, a retired oil executive, converted to Judaism thirty-seven years ago. Great-grandson Levi was just accepted at Brown University. His mother, Barbara, a former Ms. Schenectady, is over the moon about this acceptance. Then there’s Iris’s son, Adam, a playwright allegedly of some renown, and his wife, Natalie, and their three sons and two daughters: Todd, Mira, David, Hannah, and Caleb, in descending order. We are only grazing the surface here, but I’m sure you get the idea. In the sum of my exchanges with Iris, which total four, I have contributed all of twelve words.

But at least Iris Pearlman is not nosy like Mrs. Messinger, who sees fit to entrust me with any and every shred of gossip she can amass, a litany of dubious particulars comprising sexual innuendo, marital complications, deaths, near deaths, projected deaths, alleged UTIs, and colorectal surgeries. As an intensely personal sort, I could never abide gossip. I find Mrs. Messinger to be, in a word, odious, and to be avoided even more emphatically than Mrs. Pearlman, who means no harm.

There are dozens of others here at Desert Greens, too many to catalog, thus I’ll spare you a further inventory. Apologies if these assessments of my peers seem unkind. I harbor for these venerable souls no grudge whatsoever. Like me, many of my elderly neighbors live in relative isolation, receiving infrequent visitors. Their lives have become very small. I feel for them, I do. But not even one of them carries a light in their eyes that suggests they have ever lived before and remember it. Some of them can hardly remember their own names. I want to pity them. But the truth is I envy them, because most of them will probably win the death lottery. A few more years of habitually eating their big meal early in the day, collecting newspaper clippings for the sons and daughters who never call on them, and watching the five o’clock news, and the six o’clock news, and the seven o’clock news. Most of them will likely enjoy the opportunity to call it quits, while it seems that I am destined to go on living again and again.

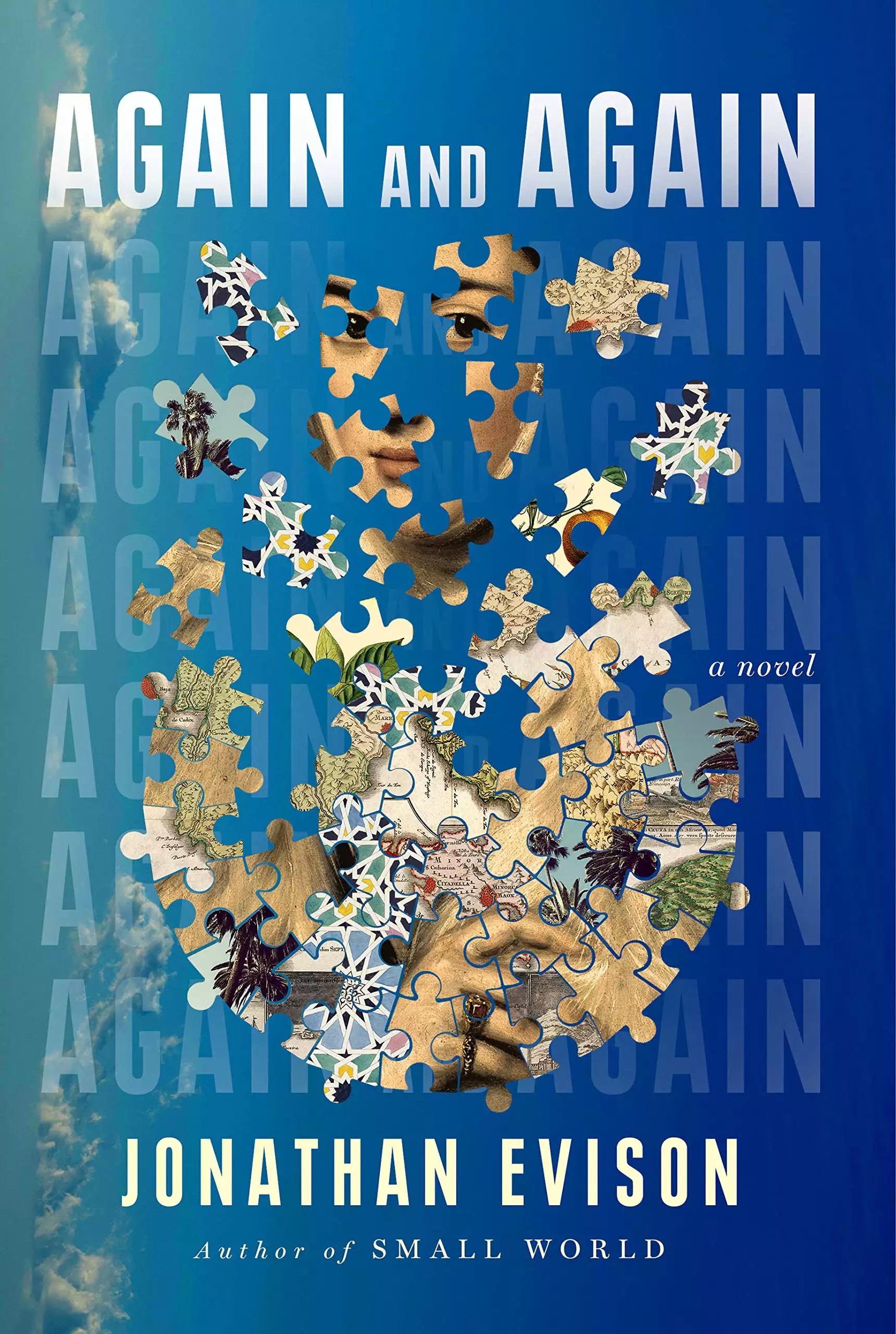

I’ve not received a visitor in eight years. Such is my desire for isolation at this point that I have zero interest in talking to anyone beyond my perfunctory exchanges with the staff. Instead, I keep to myself, confounding my meaningless but endlessly stubborn life force. I soothe my restlessness with jigsaw puzzles depicting cats sprawled on bookshelves, lighted cityscapes, national parks, famous book covers, and locales familiar to me, most of them five to fifteen hundred pieces. It’s not that I take any joy in jigsaw puzzles beyond the small satisfaction attending their completion, it is simply that they keep me occupied and focused, anchored to the one existence I hope to be my last.

Understand, I am not depressed, merely resigned to my isolation because it takes the least amount of effort. All my life I’ve tried to connect, and most of my life I’ve failed. My lone aspiration now is to ride this life out, and it seems that the less connecting I do, the less I reach out to the world, the less I’m inviting future probabilities.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved