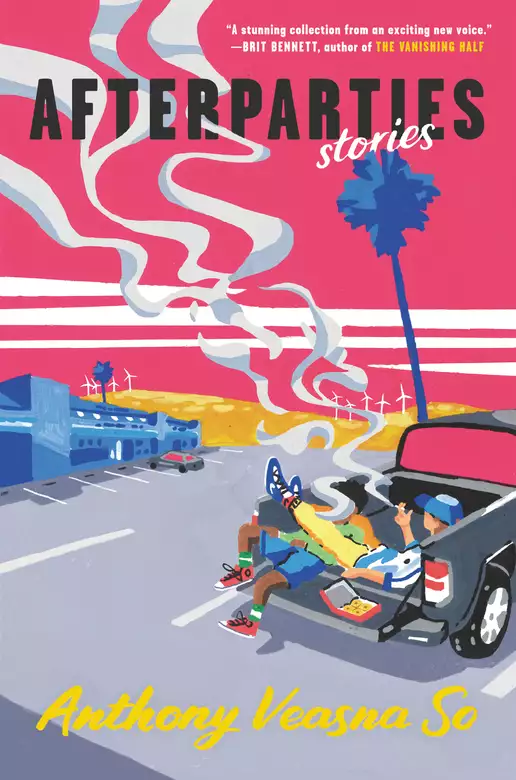

Afterparties

- eBook

- Paperback

- Audiobook

- Hardcover

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Seamlessly transitioning between the absurd and the tender-hearted, balancing acerbic humour with sharp emotional depth, Afterparties offers an expansive portrait of the lives of Cambodian-Americans. As the children of refugees carve out radical new paths for themselves in California, they shoulder the inherited weight of the Khmer Rouge genocide and grapple with the complexities of race, sexuality, friendship and family.

A high school badminton coach and failing grocery store owner tries to relive his glory days by beating a rising star teenage player. Two drunken brothers attend a wedding afterparty and hatch a plan to expose their shady uncle's snubbing of the bride and groom. A queer love affair sparks between an older tech entrepreneur trying to launch a 'safe space' app and a disillusioned young teacher obsessed with Moby-Dick. And in the sweeping final story, a nine-year-old child learns that his mother survived a racist school shooter.

With nuanced emotional precision, gritty humour and compassionate insight into the intimacy of queer and immigrant communities, the stories in Afterparties deliver an explosive introduction to the work of Anthony Veasna So.

“A stunning collection from an exciting new voice.” BRIT BENNETT, author of The Vanishing Half

“A bright and fearless debut, full of heart, joy and unforgettable characters.” DOUGLAS STUART

“I was in awe through the entire collection - and you will be, too. Afterparties is an actual marvel. “BRYAN WASHINGTON, author of Lot and Memorial

“A wildly energetic, heartfelt, original debut by a young writer of exceptional promise. These stories, powered by So's skill with the telling detail, are like beams of wry, affectionate light, falling from different directions on a complicated, struggling, beloved American community.” GEORGE SAUNDERS

“The mind-frying hilarity of Anthony Veasna So's first book of fiction settles him as the genius of social satire our age needs now more than ever. Few writers can handle firm plot action and wrenching pathos in such elegant prose. This unforgettable new voice is at once poetic and laugh-out-loud funny. “ MARY KARR, author of The Liars' Club

“Anthony Veasna So is a terrific writer. These wild, complex and funny stories are brilliant in every way. One of the most exciting debuts of the past decade.” DANA SPIOTTA, author of Innocents and Others

“Karen Russell, Carmen Maria Machado, Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah - you can count on one hand the authors of this century whose debut short-story collections are as prodigious and career-making as Afterparties.” Jonathan Dee, author of The Privileges

Release date: August 15, 2021

Publisher: Ecco

Print pages: 256

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Afterparties

Anthony Veasna So

The first night the man orders an apple fritter, it is three in the morning, the streetlamp is broken, and California Delta mist obscures the waterfront’s run-down buildings, except for Chuck’s Donuts, with its cool fluorescent glow. “Isn’t it a bit early for an apple fritter?” the owner’s twelve-year-old daughter, Kayley, deadpans from behind the counter, and Tevy, four years older, rolls her eyes and says to her sister, “You watch too much TV.”

The man ignores them both, sits down at a booth, and proceeds to stare out the window, at the busted potential of this small city’s downtown. Kayley studies the man’s reflection in the window. He’s older but not old, younger than her parents, and his wiry mustache seems misplaced, from a different decade. His face wears an expression full of those mixed-up emotions that only adults must feel, like plaintive, say, or wretched. His light-gray suit is disheveled, his tie undone.

An hour passes. Kayley whispers to Tevy, “It looks like he’s just staring at his own face,” to which Tevy says, “I’m trying to study.”

The man finally leaves. His apple fritter remains untouched on the table.

“What a trip,” Kayley says. “Wonder if he’s Cambodian.”

“Not every Asian person in this city is Cambodian,” Tevy says.

Approaching the empty booth, Kayley examines the apple fritter more closely. “Why would you come in here, sit for an hour, and not eat?”

Tevy stays focused on the open book resting on the laminate countertop.

Their mom walks in from the kitchen, holding a tray of glazed donuts. She is the owner, though she isn’t named Chuck—her name is Sothy—and she’s never met a Chuck in her life; she simply thought the name was American enough to draw customers. She slides the tray into a cooling rack, then scans the room to make sure her daughters have not let another homeless man inside.

“How can the streetlamp be out?” Sothy exclaims. “Again!” She approaches the windows and tries to look outside but sees mostly her own reflection—stubby limbs sprouting from a grease-stained apron, a plump face topped by a cheap hairnet. This is a needlessly harsh view of herself, but Sothy’s perception of the world becomes distorted when she stays in the kitchen too long, kneading dough until time itself seems measured in the number of donuts produced. “We will lose customers if this keeps happening.”

“It’s fine,” Tevy says, not looking up from her book. “A customer just came in.”

“Yeah, this weird man sat here for, like, an hour,” Kayley says.

“How many donuts did he buy?” Sothy asks.

“Just that,” Kayley says, pointing at the apple fritter still sitting on the table.

Sothy sighs. “Tevy, call PG&E.”

Tevy looks up from her book. “They aren’t gonna answer.”

“Leave a message,” Sothy says, glaring at her older daughter.

“I bet we can resell this apple fritter,” Kayley says. “I swear, he didn’t touch it. I watched him the whole time.”

“Kayley, don’t stare at customers,” Sothy says, before returning to the kitchen, where she starts prepping more dough, wondering yet again how practical it is to drag her daughters here every night. Maybe Chuck’s Donuts should be open during normal times only, not for twenty-four hours each day, and maybe her daughters should go live with their father, at least some of the time, even if he can hardly be trusted after what he pulled.

She contemplates her hands, the skin discolored and rough, at once wrinkled and sinewy. They are the hands of her mother, who fried homemade cha quai in the markets of Battambang until she grew old and tired and the markets disappeared and her hands went from twisting dough to picking rice in order to serve the Communist ideals of a genocidal regime. How funny, Sothy thinks, that decades after the camps, she lives here in Central California, as a business owner, with her American-born Cambodian daughters who have grown healthy and stubborn, and still, in this new life she has created, her hands have aged into her mother’s.

WEEKS AGO, Sothy’s only nighttime employee quit. Tired, he said, of her limited kitchen, of his warped sleeping schedule, of how his dreams had slipped into a deranged place. And so a deal was struck for the summer: Sothy would refrain from hiring a new employee until September, and Tevy and Kayley would work alongside their mother, with the money saved going directly into their college funds. Inverting their lives, Tevy and Kayley would sleep during the hot, oppressive days, manning the cash register at night.

Despite some initial indignation, Tevy and Kayley of course agreed. The first two years after it opened—when Kayley was eight, Tevy not yet stricken by teenage resentment, and Sothy still married—Chuck’s Donuts seemed blessed with good business. Imagine the downtown streets before the housing crisis, before the city declared bankruptcy and became the foreclosure capital of America. Imagine Chuck’s Donuts surrounded by bustling bars and restaurants and a new IMAX movie theater, all filled with people still in denial about their impossible mortgages. Consider Tevy and Kayley at Chuck’s Donuts after school each day—how they developed inside jokes with their mother, how they sold donuts so fast they felt like athletes, and how they looked out the store windows and saw a whirl of energy circling them.

Now consider how, in the wake of learning about their father’s second family, in the next town over, Tevy and Kayley cling to their memories of Chuck’s Donuts. Even with the recession wiping out almost every downtown business, and driving away their nighttime customers, save for the odd worn-out worker from the nearby hospital, consider these summer nights, endless under the fluorescent lights, the family’s last pillars of support. Imagine Chuck’s Donuts a mausoleum to their glorious past.

THE SECOND NIGHT THE MAN orders an apple fritter, he sits in the same booth. It is one in the morning, though the streetlamp still emits a dark nothing. He stares out the window all the same, and once more leaves his apple fritter untouched. Three days have passed since his first visit. Kayley crouches down, hiding behind the counter, as she watches the man through the donut display case. He wears a medium-gray suit, she notes, instead of the light-gray one, and his hair seems greasier.

“Isn’t it weird that his hair is greasier than last time even though it’s earlier in the night?” she asks Tevy, to which Tevy, deep in her book, answers, “That’s a false causality, to assume that his hair grease is a direct result of time passing.”

And Kayley responds, “Well, doesn’t your hair get greasier throughout the day?”

And Tevy says, “You can’t assume that all hair gets greasy. Like, we know your hair gets gross in the summer.”

And Sothy, walking in, says, “Her hair wouldn’t be greasy if she washed it.” She wraps her arm around Kayley, pulls her close, and sniffs her head. “You smell bad, oun. How did I raise such a dirty daughter?” she says loudly.

“Like mother, like daughter,” Tevy says, and Sothy whacks her head.

“Isn’t that a false causality?” Kayley asks. “Assuming I’m like Mom just because I’m her daughter.” She points at her sister’s book. “Whoever wrote that would be ashamed of you.”

Tevy closes her book and slams it into Kayley’s side, whereupon Kayley digs her ragged nails into Tevy’s arm, all of which prompts Sothy to grab them both by their wrists as she dresses them down in Khmer. As her mother’s grip tightens around her wrist, Kayley sees, from the corner of her eye, that the man has turned away from the window and is looking directly at them, all three of them “acting like hotheads,” as her father used to say. The man’s face seems flush with disapproval, and, in this moment, she wishes she were invisible.

Still gripping her daughters’ wrists, Sothy starts pulling them toward the kitchen’s swinging doors. “Help me glaze the donuts!” she commands. “I’m tired of doing everything!”

“We can’t just leave this man in the seating area,” Kayley protests, through clenched teeth.

Sothy glances at the man. “He’s fine,” she says. “He’s Khmer.”

“You don’t need to drag me,” Tevy says, breaking free from her mother’s grip, but it’s too late, and they are in the kitchen, overdosing on the smell of yeast and burning air from the ovens.

Sothy, Tevy, and Kayley gather around the kitchen island. Trays of freshly fried dough, golden and bare, sit next to a bath of glaze. Sothy picks up a naked donut and dips it into the glaze. When she lifts the donut back into the air, trails of white goo trickle off it.

Kayley looks at the kitchen doors. “What if this entire time that man hasn’t been staring out the window?” she asks Tevy. “What if he’s been watching us in the reflection?”

“It’s kind of impossible not to do both at the same time,” Tevy answers, and she dunks two donuts into the glaze, one in each hand.

“That’s just so creepy,” Kayley says, an exhilaration blooming within her.

“Get to work,” Sothy snaps.

Kayley sighs and picks up a donut.

ANNOYED AS SHE IS by Kayley’s whims, Tevy cannot deny being intrigued by the man as well. Who is he, anyway? Is he so rich he can buy apple fritters only to let them sit uneaten? By his fifth visit, his fifth untouched apple fritter, his fifth decision to sit in the same booth, Tevy finds the man worthy of observation, inquiry, and analysis—a subject she might even write about for her philosophy paper.

The summer class she’s taking, at the community college next to the abandoned mall, is called “Knowing.” Surely writing about this man, and the questions that arise when confronting him as a philosophical subject, could earn Tevy an A in her class, which would impress college admissions committees next year. Maybe it would even win her a fancy scholarship, allow her to escape this depressed city.

“Knowing” initially caught Tevy’s eye because it didn’t require any prior math classes; the coursework involved only reading, writing a fifteen-page paper, and attending morning lectures, which she could do before going home to sleep in the afternoon. Tevy doesn’t understand most of the texts, but then neither does the professor, she speculates, who looks like a homeless man the community college found on the street. Still, reading Wittgenstein is a compelling enough way to pass the dead hours of the night.

Tevy’s philosophical interest in the man was sparked when her mother revealed that she knew, from only a glance, that he was Khmer.

“Like, how can you be sure?” Kayley whispered on the man’s third visit, wrinkling her nose in doubt.

Sothy finished arranging the donuts in the display case, then glanced at the man and said, “Of course he is Khmer.” And that of course compelled Tevy to raise her head from her book. Of course, her mother’s condescending voice echoed, the words ping-ponging through Tevy’s head, as she stared at the man. Of course, of course.

Throughout her sixteen years of life, her parents’ ability to intuit all aspects of being Khmer, or emphatically not being Khmer, has always amazed and frustrated Tevy. She’d do something as simple as drink a glass of ice water, and her father, from across the room, would bellow, “There were no ice cubes in the genocide!” Then he’d lament, “How did my kids become so not Khmer?” before bursting into rueful laughter. Other times, she’d eat a piece of dried fish or scratch her scalp or walk with a certain gait, and her father would smile and say, “Now I know you are Khmer.”

What does it mean to be Khmer, anyway? How does one know what is and is not Khmer? Have most Khmer people always known, deep down, that they’re Khmer? Are there feelings Khmer people experience that others don’t?

Variations of these questions used to flash through Tevy’s mind whenever her father visited them at Chuck’s Donuts, back before the divorce. Carrying a container of papaya salad, he’d step into the middle of the room, and, ignoring any customers, he’d sniff his papaya salad and shout, “Nothing makes me feel more Khmer than the smell of fish sauce and fried dough!”

Being Khmer, as far as Tevy can tell, can’t be reduced to the brown skin, black hair, and prominent cheekbones that she shares with her mother and sister. Khmer-ness can manifest as anything, from the color of your cuticles to the particular way your butt goes numb when you sit in a chair too long, and even so, Tevy has recognized nothing she has ever done as being notably Khmer. And now that she’s old enough to disavow her lying cheater of a father, Tevy feels completely detached from what she was apparently born as. Unable to imagine what her father felt as he stood in Chuck’s Donuts sniffing fish sauce, she can only laugh. Even now, when she can no longer stomach seeing him, she laughs when she thinks about her father.

Tevy carries little guilt about her detachment from her culture. At times, though, she feels overwhelmed, as if her thoughts are coiling through her brain, as if her head will explode. This is what drives her to join Kayley in the pursuit of discovering all there is to know about the man.

ONE NIGHT, Kayley decides that the man is the spitting image of her father. It’s unreal, she argues. “Just look at him,” she mutters, changing the coffee filters in the industrial brewers. “They have the same chin. Same hair. Same everything.”

Sothy, placing fresh donuts in the display case, responds, “Be careful with those machines.”

“Dumbass,” Tevy hisses, refilling the canisters of cream and sugar. “Don’t you think Mom would’ve noticed by now if he looked like Dad?”

By this point, Sothy, Tevy, and Kayley have grown accustomed to the man’s presence, aware that on any given night he might appear sometime between midnight and four. The daughters whisper about him, half hoping that where he sits is out of earshot, half hoping he’ll overhear them. Kayley speculates about his motives: if he’s a police officer on a stakeout, say, or a criminal on the run. She deliberates over whether he’s a good man or a bad one. Tevy, on the other hand, theorizes about the man’s purpose—if, for example, he feels detached from the world and can center himself only here, in Chuck’s Donuts, around other Khmer people. Both sisters wonder about his life: the kind of women he attracts and has dated; the women he has spurned; whether he has siblings, or kids; whether he looks more like his mother or his father.

Sothy ignores them. She is tired of thinking about other people, especially these customers from whom she barely profits.

“Mom, you see what I’m seeing, right?” Kayley says, to no response. “You’re not even listening, are you?”

“Why should she listen to you?” Tevy snaps.

Kayley throws her arms up. “You’re just being mean because you think the man is hot,” she retorts. “You basically said so yesterday. You’re like this gross person who thinks her dad is hot, only now you’re taking it out on me. And he looks just like Dad, for your information. I brought a picture to prove it.” She pulls a photograph from her pocket and holds it up with one hand.

Bright red sears itself onto Tevy’s cheeks. “I did not say that,” she states, and, from across the counter, she tries to snatch the photo from Kayley, only to succeed in knocking an industrial coffee brewer to the ground.

Hearing metal parts clang on the ground and scatter, Sothy finally turns her attention to her daughters. “What did I tell you, Kayley!” she yells, her entire face tense with anger.

“Why are you yelling at me? This is her fault!” Kayley gestures wildly toward her sister. Tevy, seeing the opportunity, grabs the photo. “Give that back to me,” Kayley demands. “You don’t even like Dad. You never have.”

And Tevy says, “Then you’re contradicting yourself, aren’t you?” Her face still burning, she tries to recapture an even, analytical tone. “So which is it? Am I in love with Dad or do I, like, hate him? You are so stupid. I wasn’t saying the man was hot, anyway. I just pointed out that he’s not, like, ugly.”

“I’m tired of this bullshit,” Kayley responds. “You guys treat me like I’m nothing.”

Surveying the damage her daughters have caused, Sothy snatches the photograph from Tevy. “Clean this mess up!” she yells, and then walks out of the seating area, exasperated.

In the bathroom, Sothy splashes water on her face. She looks at her reflection in the mirror, noticing the bags under her eyes, the wrinkles fracturing her skin, then she looks down at the photo she’s laid next to the faucet. Her ex-husband’s youth taunts her with its boyish charm. She cannot imagine the young man in this image—decked out in his tight polo and acid-washed jeans, high on his newfound citizenship—becoming the father who has infected her daughters with so much anxious energy, and who has abandoned her, middle-aged, with obligations she can barely fulfill alone.

Stuffing the photo into the pocket of her apron, Sothy gathers her composure. Had she not left her daughters, she would have seen the man get up from the booth, turn to face the two girls, and walk into the hallway that leads to the bathroom. She would not have opened the bathroom door to find this man towering over her with his silent, sulking presence. And she would never have recognized it, the uncanny resemblance to her ex-husband that her youngest daughter has been raving about all night.

But Sothy does now register the resemblance, along with a sudden pain in her gut. The man’s gaze slams into her, like a punch. It beams a focused chaos, a dim malice, and even though the man merely drifts past her, taking her place in the bathroom, Sothy can’t help but think, They’ve come for us.

SINCE HER DIVORCE, Sothy has worked through her days weighed down by the pressure of supporting her daughters without her ex-husband. Exhaustion grinds away at her bones. Her wrists rattle with carpal tunnel syndrome. And rest is not an option. If anything, it consumes more of her energy. A lull in her day, a moment to reflect, and the resentment comes crashing down over her. It isn’t the cheating she’s mad about, the affair, her daughters’ frivolous stepmother who calls her with misguided attempts at reconciliation. Her attraction to her ex-husband, and his to her, dissolved at a steady rate after her first pregnancy. The same cannot be said of their financial contract. That imploded spectacularly.

Her daughters have no idea, but when Sothy opened Chuck’s Donuts it was with the help of a generous loan from her ex-husband’s distant uncle, an influential business tycoon based in Phnom Penh with a reputation for funding political corruption. She’d heard wild rumors about this uncle, even here in California—that he was responsible for the imprisonment of the prime minister’s main political opponent, that he’d gained his riches by joining a criminal organization of ex–Khmer Rouge officials, and that he’d arranged, on behalf of powerful and petty Khmer Rouge sympathizers, the murder of Haing S. Ngor. Sothy didn’t know if she wanted to accept the uncle’s money, to be indebted to such dark forces, to commit to a life in which she would always be afraid that hit men disguised as Khmer American gangbangers might gun her and her family down and then cover it up as a simple mugging gone wrong. If even Haing S. Ngor, the Oscar-winning movie star of The Killing Fields, wasn’t safe from this fate, if he couldn’t escape the spite of the powerful, how could Sothy think that her own family would be spared? Then again, what else was Sothy supposed to do, with a GED, a husband who worked as a janitor, and two small children? How else could she and her husband stimulate their dire finances? What skills did she have, other than frying dough?

Deep down, Sothy has always understood that it was a bad idea to get into business with her ex-husband’s uncle, who, for all she knew, could have bankrolled Pol Pot’s coup. And so, now, seeing the man’s resemblance to her ex-husband, she wonders if he could be some distant gangster cousin. She fears that her past has finally caught up with her.

FOR SEVERAL DAYS, the man does not visit Chuck’s Donuts. But Sothy’s worries only deepen. They root themselves into her bones. Her daughters’ constant musings about the man only intensify her suspicion that he is a relative of her former uncle-in-law. He has come to take their lives, to torture the money out of them, perhaps to hold her daughters as collateral, investments to sell on the black market. Still, she can’t risk being impulsive, lest she provoke him. And there’s the possibility, of course, that he’s a complete stranger. Surely he would have harmed them by now. Why this performance of waiting? She keeps herself on guard, tells her daughters to be wary of the man, to call for her if he walks through the door.

Tevy has started writing her philosophy paper, and Kayley is helping her. “On Whether Being Khmer Means You Understand Khmer People,” the paper is tentatively titled. Tevy’s professor requires students to title their essays in the style of On Certainty, as if starting a title with the word Onmakes it philosophical. She decides to structure her paper as a catalog of assumptions made about the man based on the idea that he is Khmer and that the persons making these assumptions—Tevy and Kayley—are also Khmer. Each assumption will be accompanied by a paragraph discussing the validity of the assumption, which will be determined based on the answers provided by the man, to questions that Tevy and Kayley will ask him directly. Both Tevy and Kayley agree to keep the nature of the paper secret from their mother.

The sisters spend several nights refining their list of assumptions about the man. “Maybe he also grew up with parents who never liked each other,” Kayley says one night when the downtown appears less bleak, the dust and pollution lending the dark sky a red glow.

“Well, it’s not like Khmer people marry for love,” Tevy responds.

Kayley looks out the window for anything worth observing but sees only the empty street, a corner of the old downtown motel, the dull orange of the Little Caesars, which her mother hates because the manager won’t allow her customers to park in his excessively big lot. “It just seems like he’s always looking for someone, you know?” Kayley says. “Maybe he loves someone but that person doesn’t love him back.”

“Do you remember what Dad said about marriage?” Tevy asks. “He said that, after the camps, people paired up based on their skills. Two people who knew how to cook wouldn’t marry, because that would be, like, a waste. If one person in the marriage cooked, then the other person should know how to sell food. He said marriage is like the show Survivor, where you make alliances in order to live longer. He thought Survivorwas actually the most Khmer thing possible, and he would definitely win it, because the genocide was the best training he could’ve got.”

“What were their skills?” Kayley asks. “Mom’s and Dad’s?”

“The answer to that question is probably the reason they didn’t work out,” Tevy says.

“What does this have to do with the man?” Kayley asks.

And Tevy responds, “Well, if Khmer people marry for skills, as Dad says, maybe it means it’s harder for Khmer people to know how to love. Maybe we’re just bad at it—loving, you know—and maybe that’s the man’s problem.”

“Have you ever been in love?” Kayley asks.

“No,” Tevy says, and they stop talking. They can hear their mother cooking in the kitchen, the routine clanging of mixers and trays, a string of sounds that just fails to coalesce into melody.

Tevy wonders if her mother has ever loved someone romantically, if her mother is even capable of reaching beyond the realm of survival, if her mother has ever been granted any freedom from worry, and if her mother’s present carries the ability to dilate, for even a brief moment, into its own plane of suspended existence, separate from past or future. Kayley, on the other hand, wonders if her mother misses her father, and, if not, whether this means that Kayley’s own feelings of gloom, of isolation, of longing, are less valid than she believes. She wonders if the violent chasm between her parents also exists within her own body, because isn’t she just a mix of all those antithetical genes?

“Mom should start smoking,” Kayley says.

And Tevy asks, “Why?”

“It’d force her to take breaks,” Kayley says. “Every time she wanted to smoke, she’d stop working, go outside, and smoke.”

“Depends on what would kill her faster,” Tevy says. “Smoking or working too much.”

Then Kayley asks, softly, “Do you think Dad loves his new wife?”

Tevy answers, “He better.”

HERE’S HOW SOTHY AND HER ex-husband were supposed to handle their deal with the uncle: Every month, Sothy would give her then husband 20 percent of Chuck’s Donuts’ profits. Every month, her then husband would wire that money to his uncle. And every month, they would be one step closer to paying off their loan before anyone with ties to criminal activity could bat an eyelash.

Here’s what actually happened: One day, weeks before she discovered that her husband had conceived two sons with another woman while they were married, Sothy received a call at Chuck’s Donuts. It was a man speaking in Khmer, his accent thick and pure. At first, Sothy hardly understood what he was saying. His sentences were too fluid, his pronunciation too proper. He didn’t truncate his words, the way so many Khmer American immigrants did, and Sothy found herself lulled into a daze by those long-lost syllables. Then she heard what the man’s words actually meant. He was the accountant of her husband’s uncle. He was asking about their loan, whether they had any intention of paying it back. It had been years, and the uncle hadn’t received any payments, the accountant said with menacing regret.

Sothy later found out—from her husband’s guilt-stricken mistress, of all people—that her husband had used the profits she’d given him, the money intended to pay off their loan, to support his second family. In the divorce settlement, Sothy agreed not to collect child support, in exchange for sole ownership of Chuck’s Donuts, for custody of their daughters, and for her ex-husband’s promise to talk to his uncle and to eventually pay off their loan, this time with his own money. He had never intended to cheat his uncle, he proclaimed. He had simply fallen in love with another woman. It was true love. What else could he do? And, of course, he had an obligation to his other children, the sons who bore his name.

Still, he promised to right this wrong. But how can Sothy trust her ex-husband? Will a man sent by the uncle one day appear at her doorstep, or at Chuck’s Donuts, or in the alley behind Chuck’s Donuts, and right their wrong for them? A promise is a promise, yet, in the end, it is only that.

AN ENTIRE WEEK HAS PASSED since the man’s last visit. Sothy’s fears have begun to wane. There are too many donuts to make, too many bills to pay. It helped, too, when she called her ex-husband to yell at him.

“You selfish pig of a man,” she said. “You better be paying your uncle back. You better not put your daughters in danger. You better not be doing the same things you’ve always done—thinking only about yourself and what you want. I can’t even talk to you right now. If your uncle sends someone to collect money from me, I will tell him how disgraceful you are. I will tell him how to find you and then you’ll face the consequences of being who you are, who you’ve always been. Remember, I know you better than anyone.”

She hung up before he could respond, and even though this call hasn’t gained her any real security, she feels better. She almost wants the man to be a hit man sent by the uncle so that she can direct him straight to her ex-husband. Not that she wants her ex-husband to be killed. But she does want to see him punished.

The night the man returns, Sothy, Tevy, and Kayley are preparing a catering order for the hospital three blocks over. Sothy needs to deliver a hundred donuts to the hospital before eleven thirty. The gig pays good money, more money than Chuck’s Donuts has made all month. Sothy would rather not leave her daughters alone, but she cannot send them to deliver the donuts. She’ll be gone only an hour. And what can happen? The man never shows up before midnight, anyway.

Just in case, she decides to close the store during her delivery. “Keep this door locked while I’m gone,” she tells her daughters after loading her car.

“Why are you so insecure about everything?” Tevy says.

And Kayley says, “We’re not babies.”

Sothy looks them in the eyes. “Please, be safe.”

The door is locked, but the owners’ daughters are clearly inside; you can see them through the illuminated windows, sitting at the counter. So the man stands at the glass door and waits. He stares at the daughters until they notice a shadow in a suit hovering outside.

The man waves for them to let him enter, and Kayley says to her sister, “Weird—it looks like he’s been in a fight.”

And Tevy, noticing the man’s messy hair and haunted expression, says, “We need to interview him.” She hesitates just a moment before unlocking the door, cracking it open. Inflamed scratches crisscross his neck. Smudges of dirt mottle his wrinkled white shirt.

“I need to get inside,” he says gravely. It’s the only thing Tevy has heard him say other than “I’ll have an apple fritter.”

“Our mom told us not to let anyone in,” Tevy says.

“I need to get inside,” the man repeats, and who is Tevy to ignore the man’s sense of purpose?

“Fine,” Tevy says, “but you have to let me interview you for a class assignment.” She looks him over again, considers his bedraggled appearance. “And you still need to buy something.”

The man nods and Tevy opens the door for him. As he crosses the threshold, dread washes over Kayley as she becomes aware of the fact that she and her sister know nothing at all about the man. All their deliberations concerning his presence have gotten them nowhere, really, and right now the only things Kayley truly knows are: she is a child; her sister is not quite an adult; and they are betraying their mother’s wishes.

Soon Tevy and Kayley are sitting across from the man in his booth. Scribbled notes and an apple fritter are laid out between them on the table. The man stares out the window, as always, and, as always, the sisters study his face.

“Should we start?” Tevy asks.

The man says nothing.

Tevy tries again. “Can we start?”

“Yes, we can start,” the man says, still staring out into the dark night.

THE INTERVIEW BEGINS with the question “You’re Khmer, right?” and then a pause, a consideration. Tevy meant this to be a softball question, a warm-up for her groundbreaking points of investigation, but the man’s silence unnerves her.

Finally, the man speaks. “I am from Cambodia, but I’m not Cambodian. I’m not Khmer.”

And Tevy, feeling sick to her stomach, asks, “Wait, what do you mean?” She looks at her notes, but they aren’t any help. She looks at Kayley, but she isn’t any help, either. Her sister is as confused as she is.

“My family is Chinese,” the man continues. “For several generations, we’ve married Chinese Cambodians.”

“Okay, so you are Chinese ethnically, and not Khmer ethnically, but you’re still Cambodian, right?” Tevy asks.

“Only I call myself Chinese,” the man answers.

“But your family has lived in Cambodia for generations?” Kayley interjects.

“Yes.”

“And you and your family survived the Khmer Rouge regime?” Tevy asks.

Again, the man answers, “Yes.”

“So do you speak Khmer or Chinese?”

The man answers, “I speak Khmer.”

“Do you celebrate Cambodian New Year?”

Again, the man answers, “Yes.”

“Do you eat rotten fish?” Kayley asks.

“Prahok?” the man asks. “Yes, I do.”

“Do you buy food from the Khmer grocery store or the Chinese one?” Tevy asks.

The man answers, “Khmer.”

“What’s the difference between a Chinese family living in Cambodia and a Khmer family living in Cambodia?” Tevy asks. “Aren’t they both still Cambodian? If they both speak Khmer, if they both survived the same experiences, if they both do the same things, wouldn’t that make a Chinese family living in Cambodia somewhat Cambodian?”

The man doesn’t look at Tevy or Kayley. Throughout the interview, his eyes have searched for something outside. “My father told me that I am Chinese,” the man answers. “He told me that his sons, like all other sons in our family, should marry only Chinese women.”

“Well, what about being American?” Tevy asks. “Do you consider yourself American?”

The man answers, “I live in America, and I am Chinese.”

“So you don’t consider yourself Cambodian at all?” Kayley asks.

He turns his gaze away from the window. For the first time in their conversation, he considers the sisters who are sitting across from him. “You two don’t look Khmer,” he says. “You look like you have Chinese blood.”

“How can you tell?” Tevy asks, startled, her cheeks burning.

The man answers, “It’s in the face.”

“Well, we are,” Tevy says. “Khmer, I mean.”

And Kayley says, “Actually, I think Mom said once that her great-grandfather was Chinese.”

“Shut up,” Tevy says.

And Kayley responds, “God, I was just saying.”

The man stops looking at them. “We’re done here. I need to focus.”

“But I haven’t asked my real questions,” Tevy protests.

The man says, “One more question.”

“Why do you never eat the apple fritters you buy?” Kayley blurts out, before Tevy can even glance at her notes.

“I don’t like donuts,” the man answers.

The conversation comes to a halt, as Tevy finds this latest answer the most convincing argument the man has made for not being Khmer.

“You can’t be serious,” Kayley says after a moment. “Then why do you buy so many apple fritters?”

The man doesn’t answer. His eyes straining, he leans even closer to the window’s surface, almost grazing the glass with his nose.

Tevy looks down at the backs of her hands. She examines the lightness of her brown skin. She remembers how in elementary school she always got so mad at the white kids who misidentified her as Chinese, sometimes even getting into fights with them on the bus. And she remembers her father consoling her in his truck at the bus stop. “I know I joke around a lot,” he said once, his hand on her shoulder. “But you are Khmer, through and through. You should know that.”

Tevy examines the man’s reflection. His vision of the world disappoints her—the idea that people are limited always to what their fathers tell them. Then Tevy notices her sister reeling in discomfort.

“No,” Kayley says, hitting the table with her fists. “You have to have a better answer than that. You can’t just come in here almost every night, order an apple fritter, not eat it, and then tell us you don’t like donuts.” Breathing heavily, Kayley leans forward, the edge of the table cutting into her ribs.

“Kayley,” Tevy says, concerned. “What’s going on with you?”

“Be quiet!” the man yells abruptly, still staring out the window, violently swinging his arm.

Shocked into a frozen silence, the sisters don’t know how to respond, and can only watch as the man stands up, clenching his fists, and charges into the center of the seating area. Right then, a woman—probably Khmer, or maybe Chinese Cambodian, or maybe just Chinese—bursts into Chuck’s Donuts and starts striking the man with her purse.

“So you’re spying on me?” the woman screams.

She is covered in bruises, the sisters see, her left eye nearly swollen shut. They stay in the booth, pressed against the cold glass of the window.

“You beat your own wife, and you spy on her,” she says, now battering the man, her husband, with slaps. “You’re—”

The man tries to push his wife away, but she hurls her body into his, and then they are on the ground, the woman on top of the man, slapping his head over and over again.

“You’re scum, you’re scum,” the woman shrieks, and the sisters have no idea how to stop the violence that is unfolding before them, or whether they should try. They cannot even say whom they feel aligned with—the man, to whose presence they have grown attached, or the bruised woman, whose explosive anger toward the man appears warranted. They remember those punctuated moments of Chuck’s Donuts’ past, before the recession forced people into paralysis, when the dark energy of their city barreled into the fluorescent seating area. They remember the drive-by gang shootings, the homeless men lying in the alley in heroin-induced comas, the robberies of neighboring businesses, and even of Chuck’s Donuts once; they remember how, every now and then, they panicked that their mother wouldn’t make it home. They remember the underbelly of their glorious past.

The man is now on top of the woman. He screams, “You’ve betrayed me.” He punches her face. The sisters shut their eyes and wish for the man to go away, and the woman, too. They wish this couple had never set foot in Chuck’s Donuts, and they keep their eyes closed, holding each other, until suddenly they hear a loud blow, then another, followed by a dull thud.

Their eyes flick open to find their mother helping the woman sit upright. On the ground lies a cast-iron pan, the one that’s used when the rare customer orders an egg sandwich, and beside it, unconscious, the man, blood leaking from his head. Brushing hair out of the woman’s face, their mother consoles this stranger. Their mother and the woman remain like this for a moment, neither of them acknowledging the man on the ground.

Still seated in the booth with Kayley clutching her, Tevy thinks about the signs, all the signs there have been not to trust this man. She looks down at the ground, at the blood seeping onto the floor, how the color almost matches the red laminate of the countertops. She wonders if the man, in the unconscious layers of his mind, still feels Chinese.

Then Sothy asks the woman, “Are you okay?”

But the woman, struggling to stand up, just looks at her husband.

Again, Sothy asks, “Are you okay?”

“Fuck,” the woman says, shaking her head. “Fuck, fuck, fuck.”

“It’s all right,” Sothy says, reaching to touch her, but the woman is already rushing out the door.

Emotion drains out of Sothy’s face. She is stunned by this latest abandonment, speechless, and so is Tevy, but Kayley calls after the woman, yelling, even though it’s too late, “You can’t just leave!”

And then Sothy bursts into laughter. She knows that this isn’t the appropriate response, that it will leave her daughters more disturbed, just as she knows that there are so many present liabilities—for instance, the fact that she has severely injured one of her own customers, and not even to protect her children from a vicious gangster. But she can’t stop laughing. She can’t stop thinking of the absurdity of this situation, how if she were in the woman’s shoes she also would have fled.

Finally, Sothy calms herself. “Help me clean this up,” she says, facing her daughters, giving the slightest of nods toward the man on the ground, as though he were any other mess. “Customers can’t see blood so close to the donuts.”

BOTH SOTHY AND TEVY AGREE that Kayley is too young to handle blood, so while her mother and sister prop the man up against his booth and begin cleaning the floors, Kayley calls 911 from behind the counter. She tells the operator that the man is unconscious, that he’s taken a hit to the head, and then recites the address of Chuck’s Donuts.

“You’re very close to the hospital,” the operator responds. “Can’t you take him over yourself?”

Kayley hangs up and says, “We should drive him to the hospital ourselves.” Then, watching her mother and sister, she asks, “Aren’t we supposed to not, you know, mess with a crime scene?”

And Sothy answers sternly, “We didn’t kill him.”

Balancing herself against the donut display case, Kayley watches her mother and sister mop the floor, the man’s blood dissolving into pink suds of soap and then into nothing. She thinks about her father. She wants to know whether he ever hit her mother, and if so, whether her mother ever hit him back, and whether that’s the reason her mother so naturally came to the woman’s defense. As Tevy wipes away the last trails of red, she, too, thinks of their father, but she recognizes that even if their father had been violent with their mother it wouldn’t answer, fully, any questions concerning her parents’ relationship. What concerns Tevy more is the validity of the idea that every Khmer woman—or just every woman—has to deal with someone like their father, and what the outcome is of this patient, or desperate, dealing. Can the very act of enduring result in wounds that bleed into a person’s thoughts, Tevy wonders, distorting how that person experiences the world? Only Sothy’s mind stays free of her daughters’ father. She considers instead the woman—whether her swollen eye and bruises will heal completely, whether she has anyone to care for her. Sothy pities the woman. Even though she’s afraid that the man will now sue her, that the police will not believe her side of the story, she feels grateful that she is not the woman. She understands, more than ever, how lucky she is to have rid her family of her ex-husband’s presence.

Sothy drops her mop back into its yellow bucket. “Let’s take him to the hospital.”

“Everything’s gonna be okay, right?” Kayley asks.

And Tevy responds, “Well, we can’t just leave him here.”

“Stop fighting and help me,” Sothy says, walking over to the man. She carefully lifts him up, then wraps his arm around her shoulders. Tevy and Kayley rush to the man’s other side and try to do the same.

Outside, the streetlamp is still broken, but they have grown used to the darkness. Struggling to keep the man upright, they lock the door, roll down the steel shutters, whose existence they’d almost forgotten about, for once securing Chuck’s Donuts from the world. Then they drag the man’s heavy body toward their parked car. The man, barely conscious, begins to groan. The three women of Chuck’s Donuts have a variation of the same thought. This man, they realize, didn’t mean much at all to them, lent no greater significance to their pain. They can hardly believe they’ve wasted so much time wondering about him. Yes, they think, we know this man. We’ve carried him our whole lives.

Superking Son was an artist lost in the politics of normal, assimilated life. Sure, his talents were often sidelined, as the store forced him to worry about importing enough spiky-looking fruits every month. (He recruited way too many of our Mings to carry through customs suitcases filled with jackfruit, bras padded with lychees, and panties stuffed with we-don’t-want-to-know.) Sure, he reeked of raw chicken, raw chicken feet, raw cow, raw cow tongue, raw fish, raw squid, raw crab, raw pig, raw pig intestine, and raw—like really raw—pig blood, all jellied, cubed, and stored in buckets before it was thrown into everyone’s noodle soup on Sunday mornings. When we walked into the barely air-conditioned store, we pinched our noses to stop from barfing all over aisle six, which would ruin the only aisle with American products, the one with Cokes and Red Bulls and ten-year-old Lunchables no one ate. (Though our Mas would’ve shoved their shopping carts right through our vomit, without blinking an eye, without even noticing their puking grandchildren—they’d seen much worse.) And, sure, Superking Son wasn’t nice. He could be cruel, incredibly so. Kevin won’t talk to him anymore, and Kevin was our best smasher last season.

Still, even with this in mind (and up our nostrils), we idolized Superking Son. He was a regular Magic Johnson of badminton, if such a thing could exist; a legend, that is, for the young men of this Cambo hood (a niche fanbase, admittedly). The arcs of his lobs, the gentle drifts of his drops, and the lines of his smashes could be thought of, if rendered visible, as the very edge between known and unknown. He could smash a birdie so hard, make it fly so fast, we swore that when the birdie zipped by it shattered the force field suffocating us, the one composed of our parents’ unreasonable expectations, their paranoia that our world could crumble at a moment’s notice and send us back to where we started, starving and poor and subject to a genocidal dictator. Word has it that when Superking Son was young, he was an even better player, with a full head of hair.

To us, Superking Son was our badminton coach, our shuttlecock king. That’s who he would always be. But what was he for everyone else? Well, it’s simple—he was the goddamn grocery-store boy.

WE LOOKED TO SUPERKING SON for guidance—on how to deal with our semiracist teachers, who simultaneously thought we were enterprising hoodlums and math nerds that no speak Engrish right, on whether wearing tees big enough to cover our asses was as dope as we hoped. And every time we had exciting news, some game-changing gossip we heard from our Mas, like when Gong Sook went crazy from tending to his crop of reefer before he could sell even one bushel, we headed for Superking Grocery Store. So when Kyle informed us about the new transfer kid—Justin—whom he spotted smashing birdies and doing insane lunges across the court, being all Kobe Bryant at the local open gym, we dropped our skateboards and rushed to find Superking Son.

We ran from our usual spot, the park where our peddling aunts never set up shop, the one next to the middle school that shut down from gang violence, and we ran because we couldn’t skate fast. (Our baggy shirts went down to our knees, compromising our mobility, but who cares about mobility when you look as fly as this?) It was February, and as chilly as a rainless California winter ever got, but we worked up a sweat doing all that running. By the time we found Superking Son in his back storeroom, we dripped beads of salty-ass water from head to toe. We were a crew of yellow-brown boys collapsed onto the floor, exhausted from excitement.

Superking Son greeted us by raising his palm against our faces. “You fools need to shut the fuck up so I can concentrate,” he said, even though we hadn’t uttered a word. He was talking to Cha Quai Factory Son about how many Khmer donuts he wanted to order that week. Superking Son stared intently at a clipboard, as if peering into its soul, his constant pen-chewing the only sound we could hear.

“Come on, man,” Cha Quai Factory Son said, “what’s taking you so long?” He grabbed the clipboard from Superking Son. “Just go with the usual! Why do this song and dance every week?” He pulled out his own unchewed pen, and then signed the invoice before anyone could whine about merchandising fraud. “Stop second-guessing yourself,” he added while shaking his head. “God, I’ve aged ten years waiting for you to make a decision.”

“Stop giving me shit for being a good businessman,” Superking Son said.

“This guy takes one econ class at comm and now he’s the CEO of Cambo grocery stores,” Cha Quai Factory Son teased, waving the clipboard around. “Like he’s Steve Jobs and those spoiled Chinese sausages are MacBook Airs.”

Superking Son crossed his arms over that semipudgy chest—over that layer of fat that had grown at a steady rate since he took over the store. “All right,” he said, “everyone out of my storeroom. Y’all are sweaty as fuck and I don’t want this asswipe smell sticking to my inventory. I sell food people put in their mouths, damnit.”

We urged our coach to wait, each of us frantic for approval. We raved about Justin, how he could replace Kevin as our team’s number one player, how Kyle swore he had served the best drop shots he had witnessed in the open gym all year.

“The open gym at Delta College?” Superking Son said, sarcasm stretching his every syllable into one of those diphthongs we learned about in sophomore English. An entire Shakespearean monologue nestled in the gaps between his words. “That’s not saying much. At that open gym, I’ve seen players smack their doubles partners in the face with their rackets.”

We only wanted to make the team better, so Superking Son’s reaction disheartened us. Yet it wasn’t different from what we had grown to expect from him. It wasn’t worse than that time a pregnant and morning-sick Ming was found vomiting into the frozen tuna bin, ruining a whole month’s worth of fishy profits, which inspired him to assign us two hundred burpees every day for a week. And it was nowhere close to that time his mom, while sweeping, slipped in the produce section and broke her hip, next to the bok choy, of all places. (We’re sure this was the moment he started balding. By his fifth medical payment, he looked like Bruce Willis in yellow-brownface.) We told ourselves Superking Son was simply stressed out. Everyone, including our own parents, relied on him to supply their food. He needed to restock his shelves for the upcoming month, or else mayhem would commence, we told ourselves, as if the store didn’t need to be restocked every month.

“Bring the kid to conditioning, and we’ll see how quickly one of you bastards gets whacked in the head.” He stepped over our bodies, grabbed the door, and looked down on us. “I’m serious,” he said. “Get out or I’m locking you guys in here.” His biceps flexed, that small part of his arm begging to be bigger than it was.

Cha Quai Factory Son started to leave first, but as he approached the door, he slid behind Superking Son. He massaged the shoulders of our coach, digging his big, dough-kneading hands into that perpetually tense and sore tissue. We watched as Superking Son’s eyebrows furrowed in revolt, even as his mouth was forming silent moans of pleasure. “It’s okay,” Cha Quai Factory Son said. “Let’s give this big boy his alone time so he can think about business.” Then he patted him on the stomach and jolted out the door.

Superking Son reached out to grab Cha Quai Factory Son, almost falling over in the process. He missed, by more than he would ever admit. And as he leaned forward into the gaping hole of the doorway, watching his vendor flee from his grasp, we could tell he wanted to scream out some last remark. But he didn’t. He probably couldn’t decide on anything to say.

THERE ARE STORIES OF SUPERKING SON you wouldn’t believe. Epic stories, stories that are downright implausible given the laws of physics, gravity, the limitations of the human body. There’s the one where Superking Son’s doubles partner sprained his ankle during the final match of sectionals. The kid dropped to the ground, right in the middle of the court, and Superking Son fended off the smashes of Edison’s two best varsity players by lunging over his partner’s injured body. He kept this up for ten minutes, until one of the Edison players also slipped and sprained his ankle, resulting in a historic win for our high school’s badminton team. (They later learned the floor had been polished by the janitors, who neglected to tell the badminton coaches. The guys who sprained their ankles sued the school, won a huge settlement, and now both have their own houses in Sacramento. Three bedrooms, two and a half bathrooms, everything you could possibly want.) Then there are the many times he’s beaten Cha Quai Factory Son in a singles match, often without letting him score a single point. Once, Superking Son bet Cha Quai Factory Son a hundred dollars he could beat him while eating a Big Mac, one hand gripped around his racket, the other around a juicy burger. Cha Quai Factory Son agreed, but wanted to triple the bet on the stipulation that Superking Son could not spill even a shred of lettuce. Halfway through, Superking Son had played so well, he got his friend to throw him another Big Mac, then a box of ten McNuggets. At the end of the match, the gym floor remained spotless. Cha Quai Factory Son refused to eat at McDonald’s for ten years.

We didn’t believe the stories at first. We thought, Superking Son’s talking out of his ass. He wants to hype himself up to kids over a decade younger than him. That was why he allowed us to practice skating tricks in the parking lot and gave us free Gatorades (albeit the yellow flavor no one bought, never the light blue). Then, after we had entered high school, Superking Son took over as the coach of our badminton team. Just as he’d carried his own peers as a class-ditching player in the nineties, he coached our team through a regional championship. (There weren’t opportunities to compete at state or nationals, no D1 recruiters scouting matches with athletic scholarships in their ass pockets. This was badminton, for god’s sake.) Superking Son launched us to the very top of the Central Valley standings—the first time we called ourselves number one at anything. But more than that, from the little gestures—the fluid flair of his wrists when demonstrating how to hit, his ability to pick up birdies, with only his racket and foot, and send them flying across the gym to any player he chose, the way he tapped into rallies, making shots with his left hand so as not to annihilate the kid he was coaching—we had realized the stories were true.

JUSTIN WAS NOT IMPRESSED. He was the new kid who showed up to school driving a baller Mustang, and parked it next to Kyle’s minivan, which was one of those beat-up machines abandoned at the local car shop and then flipped and sold to Cambo ladies like Kyle’s mom, who had prayed and prayed for the miraculous day their eldest children could start chauffeuring around their youngest. (We could tell, from the way Justin spiked his jet-black hair into pointy peaks, that he had the clearest intentions to paint red, yellow, and blue flames on the driver’s side of his Mustang.) So no, Justin was not impressed with the abandoned parking lots we hung out in, the mall that did so badly Old Navy closed down, the pop-up restaurants located in Cambo-rented apartments, where we slurped steaming cups of kuy teav in roach-infested kitchens, and he definitely did not see what we saw in Superking Son.

But Justin, despite the pretensions, was a damn good badminton player. Plus, after school let out, he bought us rounds of dollar-menu chicken sandwiches, giving us rides in his Mustang while we inhaled that mystery meat. And we saw where he was coming from, because this year Superking Son was indeed off.

Conditioning was a shitshow. Two weeks of Superking Son showing up late, his clothes stained with sweat (we hoped it was sweat), fish guts and pig intestines all stuck in his hair and stinking up the joint. Two weeks of him miscounting lunges and crunches and not stopping us from planking until we fell to the ground in pain—he was constantly checking his phone instead of keeping track of what we were doing. And he kept forgetting Kyle’s name. Kyle, whose dad visited Superking Grocery Store every week to buy lottery tickets and fish oil pills. (“Gotta be healthy for when I’m rich,” Kyle’s dad often said, kissing both his ticket and his pills for good luck.) Kyle, who Superking Son practically watched grow up, as his own Ma used to babysit Kyle when Kyle was still in diapers. (Babysitting, for her, entailed hours of pushing a naked infant in a shopping cart, up and down every aisle of the store.)

“What’s up with your coach, anyway?” Justin asked one day, while driving a couple of us home after practice. “I don’t mean to be a hater,” he continued, “but I could get better conditioning doing tai chi with the ladies in the park. Like, only the left half of my body is getting a workout, man, like if I kept doing this, my muscles will get all imbalanced and I’ll topple over.”

Not sure ourselves, we told him there was nothing to worry about, because sometimes Superking Son got caught up with the store. Sometimes our coach was so stressed out he didn’t think straight.

“It’s amazing that store makes money looking the way it does,” Justin said. “It’s such a dump. I hope you guys are right, though. My mom’s getting on my case about college applications. She wants me to quit badminton and join Model UN, but I keep telling her that the coach is supposed to be this legend and the team can win a bunch of tournaments. Don’t get me wrong, I wanna keep playing badminton, but . . . I mean, Model UN does have cute girls . . . girls that wear cute blazers . . . and know stuff about the world . . .”

As Justin trailed off, thinking about all the girls he could woo with his faux diplomacy and political strategy, we saw him slipping away from our world. We saw this college-bound city kid, this Mustang-driving badminton player, how he might be too good for our team, our school, our community of Cambos. Sure, Justin was Cambodian, but he seemed so different. That’s what happens when your dad’s a pharmacist, we thought. Whenever you wanted, whenever things stopped benefiting you, or whenever you simply got bored, you could just whip out something else, like a skill set in Model UN.

WE HAD THE MIND TO THROW an intervention for Superking Son. We needed to do something to keep Justin around. Every day for a week, we met during lunch as a team—sans Justin and sans Superking Son, obviously—to discuss intervention strategies, our evidence and counterarguments, who would say each point and in what order and where each of us would stand to demonstrate the appropriate amount of solidarity. We even made contingency plans, which detailed an escape route if Superking Son were to freak out and start chucking produce at our heads (it happened more often than not). But when we got to the store, ready for a confrontation, we found Superking Son in the back room surrounded by what came across as a militia, minus the rifles and bulletproof vests. We saw our Hennessy-drenched uncles, the older half siblings no one dared to talk about, and those cousins who attended our school but never seemed to be present at roll call.

Hiding behind the stacked crates, we spied on them. Superking Son was in the center of the circle, staring intently at the floor. His hand seemed stuck to his chin. Some ghostly vision played out in front of his eyes, and it shocked the color out of his face. Cha Quai Factory Son was there, too, his hands on Superking Son’s shoulders, like he was both consoling him and holding him back from doing something stupid. A wave of money flashed around the circle, stopping only to be counted and recounted, probably to make sure no one had slipped any bills into his pocket. We spied on these men, each of us brainstorming reasons for this meeting that were innocent and harmless, not doomed by the laws of faux-Buddhist, karmic retribution. If we’re being honest with ourselves, none of us figured out a reason worth a damn.

BADMINTON PRACTICE ONLY WORSENED. Superking Son coached everyone who wasn’t Justin, hardly acknowledged his existence, really, not even to reprimand him. Yet when we crowded around a Justin match and cheered as he nailed smash after smash, we swore we saw Superking Son in awe of his talent, analyzing Justin’s form and failing to find any faults. Sometimes we saw something darker, something seething, within his stares, some envy-fueled plot being calculated in his expression, but then he’d break his gaze from Justin. He’d check his phone, for the thousandth time, and allow anxiety about his father’s store to overtake, yet again, his love for badminton.

Justin, for his part, ignored Superking Son’s directions and went through practices entirely on his own agenda. That first week, they interacted only through overriding each other’s instructions to Justin’s hitting partner, Ken, that poor (we mean this literally) and unfortunate schmuck. Every practice, Superking Son told Ken to practice his drop shots, Justin said smashes, ...

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...