For some reason, I didn’t feel as woke as the women on YouTube. Armed with the leave-in conditioner from the valleys of Shea Moisture, an afro pick from across the hall in my parents’ room, and scissors from the CVS across the street, I was about to secretly cut off my hair in the comfort of the bathroom.

I was also in charge of the chores for the day. My parents and sweet little brother Ray were outside on a playdate with a new friend he already made. He deserved a friend, that one, but a friend for me? I didn’t care. Earning admission into Dean’s Merit Society was my number one goal.

As I adjusted my posture and smiled widely, I attempted to sound just like the YouTube influencers I saw a couple of hours ago.

“Hi everyone, welcome to my channel!” I’ve wanted to make a YouTube video of my own for some time now.

Too bubbly, I thought. People want sincerity.

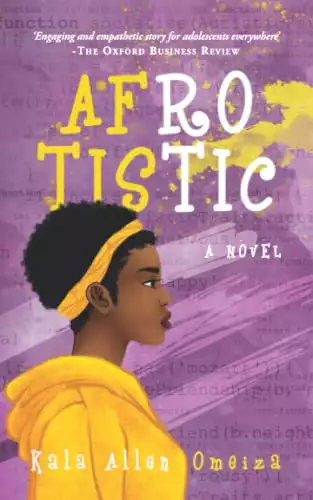

“Hi everyone! I’m Noa! I’m autistic and I’m fifteen years old. Today, I’m finally going to cut my hair!” I added a gasping face for emphasis.

Nailed it.

I planned to cut so close to my regrowth before my mom returned home with Ray that she’d have no choice but to rush me to a stylist to help me “chop” the rest of the relaxed part off. It was the only way to get noticed enough to make the elite leadership society. Well, the only way that I could think of, that is.

As I started cutting, I pulled my hair closer to the bathroom light and scrutinized the hairs landing on my sink. Black specks floated to the bottom, so thin and graceful at first, then slightly faster and thicker as I became more confident and took larger snips.

I smiled at my reflection in surprise at how quickly this was going.

New school, new me.

Back in Orlando, I struggled to fit in through middle school and my first year of high school. The students seemed to despise me as everyone seemed to be in impenetrable cliques. I felt like the Latino, White and Black students didn’t like each other. Well, the students didn’t like me rather. Except for my friend Cody, but he was someone I didn’t see that often, as he was partly homeschooled. I was just getting by from occasionally talking to Cody. It all didn’t matter anyway, as the kid betrayed me when I needed him most for my Dean’s Merit Society quest.

“Hey, what’s up, Noa?” Cody had asked blissfully earlier that day on my strict third Saturday of the month routine I made to avoid getting close to him (or anybody) on my Dean’s Merit Society quest. I skipped the pleasantries. I gave him my offer of leading an art workshop for the elementary school kids. It would be like old times, like how I rehearsed a Mozart piece by playing the oboe and automating an Artificial Intelligence Technique called Deep Learning (with some ample help from my computer scientist godmother who was researching the topic) to make a piano duet. To complete the duo that was required, Cody made an acrylic painting to match.

“It would be fun to work together again, right?” I said at the end of my dire request. I was sure it was an offer he wouldn’t resist.

Cody paused for a long time, possibly a minute. I stretched my arm out with my hand gripping my phone to elongate the distance from my loud breathing.

Finally, he said, “I’m sorry, I can’t.” I asked why. He said, “Because I’m working on a similar project with someone else, remember Annabel? I think you guys were friends in fourth grade... Or maybe not... Well anyway, because you moved across the country, and because we never talked outside of the third Saturday of the month for whatever reason, I guess you weren’t aware that I’m applying for Dean’s Merit Society here in Orlando too. Annabel and I are working on the project together in person.”

He paused. I guess he was waiting for me to respond…except I didn’t because I decided

to hang up. But then I felt bad, so I texted him three minutes later that I wished him well and that I may not reach out to him on the next third Saturday of the month. Or the months after that.

With my one friend now gone, I began to think that maybe I was the cure to racism, as it seemed all races united on one thing: the decision to avoid me. In Artificial Intelligence, a Social Network Analysis map would graph people’s friendships. Someone like Katy Perry, or a popular person at Orlando would have a very dense map. An Analysis map with my friends, however, would have yielded a graph that looked sparse, emaciated even. I wondered if the map could graph how much my unpopularity could cure racism in my new high school. To do so, I guess I needed to gather more evidence in Petersburg to make such a conclusion in my new school.

I shook my head. I sounded like one of my dad’s journal articles. He was paid to be “not entirely sure” about everything. “Genius”.

The parent duo heard me say that I hated it in Orlando, but blissfully missed my follow-up of “But it’s fine, ‘cause in three years I’ll be far away at university and things will be better there.” So, with that data, my parents still had the brilliant idea to move across the country for work and plop me in a new school for my sophomore year of high school.

“Your teachers will know about your diagnosis now. They can help tailor your studies to your learning pattern,” my dad had said. But therein lies the point. Nothing about me has changed. Instead of being “weird Noa” or “rude Noa”, I’m now “autistic Noa”.

Does autistic Noa get tailored learning, while weird and rude Noa gets told to sink or swim? And let’s not forget me being the underappreciated cure to racism––who graciously took her talents from one small town to another. This town is apparently located over five hours away from the actual New York City by car.

I guess I’d have to figure out how to manage on my own here. I managed Florida (barely), so New York will hopefully at least be tolerable.

The evidence showed that this time, I’d be tolerating as autistic, cool-afro Noa.

So how else would I get leadership experience without working with Cody?

I went on my laptop to email my former guidance counselor Ms. Smith, hoping she would make an exception under the circumstances now that I had moved to the northeast region of the country. Maybe I could iterate my robot prototype that I’d been working on for leadership experience? When I checked her previous message, I realized she wouldn’t allow exceptions.

“Unfortunately, I will not make any exceptions regarding the required leadership experience by the second marking period of the school year. You must work with at least two other individuals or a group to lead an organization within your high school and/or produce something for the greater good by the start of the second marking period of the school year. You are most welcome to be as creative or concrete as

you want in this endeavor, as long as you follow this simple specification to receive a letter of recommendation on my behalf.”

Shoot.

I had to think and move fast to achieve this experience, earn my spot in society, and use that as my ticket out of small-town America.

What did other people do in these kinds of situations?

Cry? Hustle? Makeover?

And that was it. I decided it was time to do a makeover, and all my problems would be gone afterward. I would be the new girl starting afresh. I would gain the confidence to demand to be added to multiple leadership boards. Or, maybe more realistically, l would get the guy, as that’s something that always happens. In my case, I would get Cody and Annabel to add me to their project back in Orlando and let me work remotely with them.

It was an easy fix that played out all the time in movies, novels, and TV shows. I just had to decide on how to do the makeover.

Dye my hair purple? Or orange?

No, that would be too easy. I needed something more. Something that would transform me into looking like the “new girl, new look” that I was going for. Something that would transform me into a future Petersburg West High School Dean’s Merit Society kid.

That’s when I decided that I’d do the unthinkable and cut my hair.

I looked down at the sink; the falling hairs finally stopped. There were finally no more left to trim. I looked at myself in the mirror, took a quick selfie, and then finally, with all my might, I laughed.

Wait, that's good, right?

Perhaps too strange. Viewers probably don’t like weird hair influencers.

I would have felt better about myself if I had smiled or felt one glimmer of an ability to hold it together, but apparently that was an impossible feat. Is this how the women of YouTube felt when they did this? When they big chop their hair?

Probably not. I decided I’m not like the YouTube women, and that was okay right then.

The new Noa has arrived, Buffalo. Or whatever suburb this “technically” was. I hoped that managing a new afro would be the least of my worries. With my new hairstyle, I’d gather more dense friendships for my Social Network Analysis graph. This would all allow me to have plenty of other things to accomplish, like setting up an organization, or producing something with a team all in a few weeks. No pressure.

“Genius-y”, I know. But who knew my parents’ scholarly thought could work here? I guess, in a different way, I may be as woke as the women of YouTube after all.

The door opened, then shut. I heard feet patter before an incoming voice:

“I hope you remembered to take the chicken out of the freezer Noa!”

It was my mom.

They’re back.

I flinched, bracing for the double surprise. I wondered if the charismatic Youtubers forgot their frozen chicken too.

I know I didn’t need the rest of my family’s approval of my new haircut, but I wanted it. I wanted them to see the leadership potential in me that I expected my classmates to see.

My five-year-old brother greeted me when I returned from my hair appointment with my mom, rushing to the door to jump in for a hug. Like a cannonball, Ray bolted to my chest, grasping me in a tight, warm embrace. I laughed, noticing in detail his little afro and how it now seemed to somehow be outgrowing that tiny head of his.

My dad chuckled at Ray’s enthusiasm. “Welcome to the afro club, kiddo. Now, don’t do anything else impulsive this year.” I began to worry slightly that if my parents didn’t seem to care about my afro much, then the Petersburg kids wouldn’t either. My dad walked past me to greet my mom. He kissed her on the cheek and conversed with her quietly.

My dad was diagnosed with autism in his late twenties. He always seemed to be comparing the way I felt out of place to the way he did when he was young. My mom just insisted he was paranoid.

“Hey Zainab, did you see that?” my dad would say to my mom when we were eating dinner after a pleasant day out. “Noa didn’t play with those kids at the playground. I did that when I was growing up because I couldn’t process the dialog of the other children.”

“Babe, for the last time, stop comparing Noa to yourself,” my mom would respond. “She is NOT autistic. She was just bored of those bratty kids.”

They went on and on like that, the two of them. Until Ray was born. Unlike me, he didn’t babble or utter a word by his first birthday. Or his second birthday. Or third.

Then he was five. A kind kid and nonverbal. His full name is Raymond, but we called him “Ray”, like a ray of sunshine in the impending dark Buffalo weather. A ray of light among the dark clouds. Over the years, my dad grew more adamant to test us for autism while my mom’s dismissal slowly subsided. I was old enough to see my parents' reaction to him, and it wasn’t like I thought it would be. They spoke with him, my mom whispered in her native language, Krio, about what a handsome little boy he was. My dad always read books with him ranging from elementary math to sports. They had dreams for him groaning through piano lessons and competing in programming competitions. My parents never seemed to mind that he was developing differently than what they had expected. They never threw out their dreams for him, just changed them.

He loved us all, and I could tell that Ray understood us by his actions. The way his eyes lit up, the way his hands flapped, the way his smile widened was all my parents and I received from him, but it was all we needed.

Ray was four and a half when it was confirmed he was autistic—almost a year ago.

My dad’s case for me grew stronger with my brother's diagnosis. Finally, my mom decided to take me to a specialist for a diagnosis too.

When I was confirmed, I was fifteen—nearly six months ago.

“Ready for kindergarten, Ray?” I asked, following him as he turned away. Ray walked farther into the house, past our front stairway and towards our living room. He sat down on the base of our couch. I sat by him and took out one of his toy chests hidden in a storage cube. I grabbed two bioNickle inventions.

“Beep. Boop,” I said, imitating a robot as best I could. “I’m a robot, and Noa’s hair is amazing,” I chanted in a robot tone. Ray clapped, and for a brief moment, I felt like Amandla Stenberg after a fresh trim. Then I felt even more like her upon realizing how cool of a reference Amandla Stenberg was. I noted it for school tomorrow, potentially during the usual introductions, although I had no idea how I was going to weave it in.

Ray took the bioNickles out of my hand. I shrugged, humbled by the brief attention my natural hair received from my biggest fan.

He waved them over his head, imitating a flying motion. Lips puckered as if to say, “Whoosh!” I bit my lip trying my best not to narrate for him. There was about a 50% chance that he’d love my narrations, but they were not what he’d imagined.

“Bob, let’s fly that way! I heard the shiny red dress is on sale!”

“Ugh! No, Sarah. We have to fly to the game store first!”

Those conversation dynamics were a hit sometimes, awarded with more exuberant smiles and playtime. Other times, I would be so engrossed in my narratives I would sometimes begin to feign tears or burst out laughing from my own wit. Ray would frown and push me away before covering his ears, sometimes while I was still tearing or laughing.

I’m not exactly sure what sparks the difference in reaction, but I chose not to risk the latter that time. I just watched him play, and asked questions I was genuinely curious about.

“Hey Ray, how would you make their robot brains in real life? Natural Language Processing? Or Machine Learning?”

Smiles.

“Yeah, Natural Language Processing seems most important. Wouldn’t it be cool if these guys also couldn’t speak? Maybe they can think thoughts and act on them, but can’t directly tell anyone why they acted that way?”

“Whoosh!” mimed Ray.

“Then you can take them to Sorrel Heights with you,” I said. “Everyone will think doing without speaking is cool because the robots are also doing it. Your teachers would be like, “Hey, little man, teach me to be quiet too.” I chuckled for a moment. “The world would sure be more fun if the humans trying to change you just stayed quiet instead, ...