Astra Taylor

I first read J. D. Beresford’s A World of Women in 2013, one hundred years after it was published. I turned the pages, illuminated by the faint glow of a flashlight, in a little cabin after the power was knocked out by Hurricane Sandy, which roared over upstate New York.

I had gathered provisions that would last four or five days: non-perishable goods, bottled water, batteries, firewood. The powerful storm caused the trees to bend, arching almost to the ground. The sound of trunks and branches snapping echoed through the night. That evening, before my phone died, I saw photos shared by friends who had stayed in New York City. Lower Manhattan had gone dark and flooded. Cars were floating in parking garages like apples in a barrel. People were wading down Avenue C. Subway stations had morphed into filthy aquariums.

For the next few days New Yorkers were alerted to the long-repressed fact of their city’s fragility. Buildings that had seemed immutable the day before, gleaming as part of Manhattan’s famous skyline, were dark and waterlogged, uninhabitable and abandoned. Locals reported of getting lost in neighborhoods in which they had lived for years, familiar intersections made eerie by quiet and lack of light. In hard-hit regions—lower Manhattan, the shorelines in Brooklyn, Queens, Staten Island, and New Jersey—thousands were homeless while others, elderly or infirm, were trapped in their homes. Traffic tunnels were impassable and commuter trains stuck. Gasoline was soon rationed, the lines for fuel snaking for blocks.

Though the situation was unprecedented in recent memory, people kept remarking that the experience felt oddly familiar. Sandy opened an uncanny window onto a doomsday future that we have already seen at the movies and read about in books—books like A World of Women, an early example of apocalyptic science fiction.

When I again picked up the book seven years after my initial encounter with it, the distance between fiction and reality had further closed. The novel imagines a plague that devastates humanity, and I was living through a pandemic—though fortunately not one as virulent as Beresford’s fabrication. I revisited the novel in my living room, after having barely left my home in nine months—an astonishing change in daily routine that began when the coronavirus pandemic caused the United States to shut down in March of 2020.

As of this writing, Covid-19, a disease that first emerged in Wuhan, China, has claimed over 1.5 million lives and caused a global recession, evaporating tens of millions of jobs in the United States alone. The initial epicenter of the US outbreak, New York City, was a ghost town for weeks, with sirens blaring day and night as bodies piled up in refrigerated trucks parked outside overwhelmed hospitals. In hindsight, Hurricane Sandy looked like child’s play.

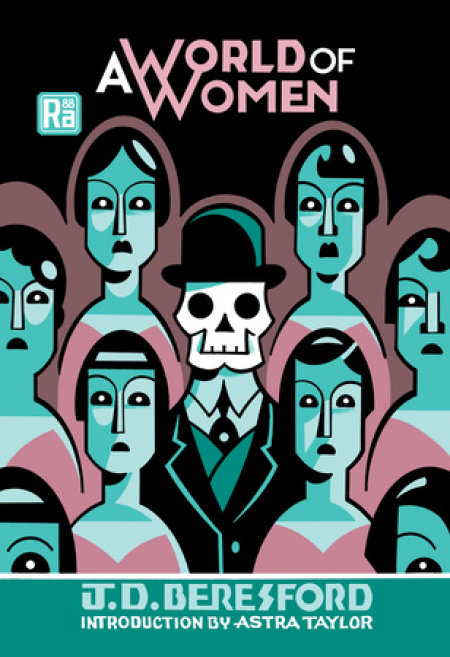

“Seems this new plague’s spreadin’ in China.” So goes the first mention of Beresford’s imaginary illness, uttered by George Gosling, a striving businessman and father whose two daughters will soon have to learn self-reliance amidst society’s wreckage. Beresford’s gripping tale, which in the UK was titled Goslings, chronicles the spread of a lethal pathogen that nearly wipes out the planet’s male population. (Mr. Gosling turns out to be one of a tiny handful of men who are immune.) As the vast majority of menfolk perish, modern civilization slowly ceases to function. London, the bustling metropolis around which the story is set, shuts down: factories no longer churn out merchandise, farms no longer produce food, Parliament empties, laws go unheeded, and nature begins to reclaim stone and steel. Women and a handful of male survivors persevere, trekking to the countryside to scratch out a life on the land.

It’s a tale of devastation, to be sure, but also one of tenacity and triumph. As civilization crumbles, Beresford’s main characters discover hidden strength and talent and the freedom to articulate criticisms of the old social order they never would have uttered otherwise. A resilient minority represents hope for a radically transformed and improved future, and an end to hierarchies based on class or gender.

Like many others, I hoped that the coronavirus would be a wake-up call, an opportunity for people to recognize a shared solidarity in vulnerability as we coped with a terrible international crisis. As frontline and essential workers heroically reported for their jobs while millions sheltered in place, we imagined that the result might be a society in which risk and reward were more fairly distributed and care work better valued. Instead, the disease provoked denial. Following President Trump’s lead, the right wing claimed it was hoax and denounced public health protocols, including simple face masks, as a form of tyranny. The president boasted of bogus miracle cures while condemning hundreds of thousands of Americans to death, and millions to destitution.

I should have known better than to be optimistic, especially with Trump at the country’s helm. Hurricane Sandy, too, was heralded as just such a turning point, and the possibility of a mass awakening about the dangers of climate change suffused my first reading of A World Of Women, which is threaded by a similar positivity. It didn’t take long for us to realize that Hurricane Sandy was not the jolt we had been hoping for. Climate change profiteers weren’t sanctioned in any way and regular people’s lives were turned upside down. In Staten Island a month after the storm, thousands of residents were still living in shelters or their cars. “The vultures are circling our community,” one woman told me during a reporting expedition. “They see valuable beachfront property, not a place where families live.”

There are vultures and hucksters in Beresford’s novel too, before and after the plague—like the lecherous and avaricious Mr. Gosling, who urges his firm to make financial investments based on the disease’s imminence; the wealthy politicians who stampede to America in an attempt to outrun fate; and the male survivors who become libertines, taking advantage of the scarcity of competition for female attention. Doubters and opportunists abound. “The Evening Chronicle has even fallen back on the ‘New Plague’ for the sake of news,” one of the novel’s characters cynically pronounces, ignorant of the devastation to come. Evangelicals crow about “judgement,” joyously convinced mass destruction signals their righteousness.

Experts promise the pestilence will work itself out, and maintain that protecting lives is bad for business: “Nevertheless, despite this one intimidating aspect of the plague, the general attitude in the middle of March was that the quarantine arrangements were enormously impeding trade and should be relaxed.”

Women too, are complicated characters, though it appears Beresford generally preferred them to their masculine counterparts: some hoard, some steal, and some even kill. While the hero and heroines of A World Of Women embrace the opportunity to build the foundation of a new society from scratch, many of the women they encounter cling to the old ways and outmoded beliefs. They judge and persecute and conform, almost as if the plague had never happened.

While Beresford takes a novelist’s pleasure in describing the pandemic’s arrival and the adventure that ensues, long passages are devoted to conceptual reflections. The plague opens a space for the expression of new ideas about how to live—ideas that overlap with the progressive values Beresford espoused. In the English countryside a group of women, aided by one thoughtful man, put some of these ideas into action, forming a sort of agrarian commune informally organized around principles of self-reliance, cooperation, and even vegetarianism. Beresford makes an impressive attempt to envision a new social order, and though he doesn’t manage to totally escape the prejudices of his day (no one does), his evident socialism and feminism resonate in this period of political turmoil and resurgent left-wing idealism.

Seen through the eyes of Beresford’s protagonists, the plague was an atrocity . . . yet it’s not clear they would turn back the clock if they could. Viewed from a certain perspective, the outbreak produced desirable social effects not easily achieved through other means: freeing women to break out of prescribed habits and social roles (smashing patriarchy by all but eliminating men), for example.

The disease also challenges our species’ delusional conviction that the Earth is our dominion. “It is no longer safe to comfort ourselves with the belief begotten of our vanity that the world was necessarily made for man,” one of the book’s central figures muses in a widely read newspaper column, published just before the printing presses cease operations. The coronavirus pandemic ought to spark a similar epiphany. Like other zoonotic diseases (avian flu, Ebola, HIV), Covid-19 jumped from another species to a human body because of our voracious encroachment on the natural world and relentless exploitation of other animals.

It’s a dark thing to put your faith in catastrophe. Though disasters do occasionally serve as turning points (Ohio’s 1969 Cuyahoga River fire, which helped lead to the establishment of the Environmental Protection Agency, is one example), more often they do not. The California forest fires that charred over four million acres in 2020 offer a depressing counterpoint. Yet some continue to cling, all the same, to the twisted logic that things have to get worse in order to get better. As the 2020 US presidential election approached, and Donald Trump faced off against Joe Biden, I occasionally heard self-identified radicals insist that a second Trump turn would somehow lead to positive social change by accelerating social breakdown. In fact, I countered, it would only hasten the arrival of authoritarianism.

It’s evident that Beresford felt the tug of similar sentiments but rightly resisted them, for the tale he tells is hardly one of straightforward redemption. The plague he invents creates an opening but offers no promises, and that’s what makes A World of Women interesting.

It doesn’t give away much to say that the novel ends with an inspiring disquisition on the future by a fearless young woman. Though he’s an unconventional and enlightened fellow, typically loquacious and opinionated, her male companion is comparatively silent, apparently dumbstruck by the force of her vision, her “great plan,” as she calls it: a world without class and sex division, without forced labor and forced marriage. It’s gender equality she craves most of all, and she details new arrangements for love and child-rearing. Almost a century later, it’s remarkable how many of the principles she outlines have become commonplace. The society we live in is far from perfect, and the coronavirus pandemic exposed some of its most brutal and absurd aspects. Nevertheless, many things have undoubtedly improved by Beresford’s measure, and we didn’t have to witness the extermination of half of the human race to get here.

How those improvements happened is a story worth retelling ourselves, as we face new and unexpected challenges.

“Where’s the gels gone to?” asked Mr Gosling.

“Up the ’Igh Road to look at the shops. I’m expectin’ ’em in every minute.”

“Ho!” said Gosling. He leaned against the dresser; the kitchen was hot with steam, and he fumbled for a handkerchief in the pocket of his black tail coat. He produced first a large red bandanna with which he blew his nose vigorously. “Snuff ’andkerchief; brought it ’ome to be washed,” he remarked, and then brought out a white handkerchief which he used to wipe his forehead.

“It’s a dirty ’abit snuff-taking,” commented Mrs Gosling.

“Well, you can’t smoke in the orfice,” replied Gosling.

“Must be doin’ somethin’, I suppose?” said his wife.

When the recital of this formula had been accomplished—it was hallowed by a precise repetition every week, and had been established now for a quarter of a century—Gosling returned to the subject in hand.

“They does a lot of lookin’ at shops,” he said, “and then nothin’ ’ll satisfy ’em but buyin’ somethin’. Why don’t they keep away from ’em?”

“Oh, well; sales begin nex’ week,” replied Mrs Gosling. “An’ that’s a thing we ’ave to consider in our circumstances.” She left the vicinity of the gas-stove, and bustled over to the dresser. “’Ere, get out of my way, do,” she went on, “an’ go up and change your coat. Dinner’ll be ready in two ticks. I shan’t wait for the gels if they ain’t in.”

“Them sales is a fraud,” remarked Gosling, but he did not stop to argue the point.

He went upstairs and changed his respectable “morning” coat for a short alpaca jacket, slipped his cuffs over his hands, put one inside the other and placed them in their customary position on the chest of drawers, changed his boots for carpet slippers, wetted his hair brush and carefully plastered down a long wisp of grey hair over the top of his bald head, and then went into the bathroom to wash his hands.

There had been a time in George Gosling’s history when he had not been so regardful of the decencies of life. But he was a man of position now, and his two daughters insisted on these ceremonial observances.

Gosling was one of the world’s successes. He had started life as a National School boy, ...