- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

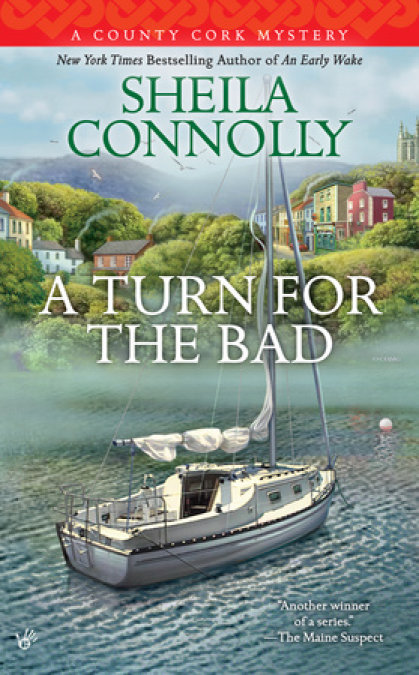

After calling Ireland home for six months, Boston expat Maura Donovan still has a lot to learn about Irish ways-and Sullivan's Pub is her classroom. Maura didn't only inherit a business, she inherited a tight-knit community. And when a tragedy strikes, it's the talk of the pub. A local farmer, out for a stroll on the beach with his young son, has mysteriously disappeared. Did he drown? Kill himself? The child can say only that he saw a boat.

Everyone from the local gardai to the Coast Guard is scouring the Cork coast, but when a body is finally brought ashore, it's the wrong man. An accidental drowning or something more sinister? Trusting the words of the boy and listening to the suspicions of her employee Mick that the missing farmer might have run afoul of smugglers, Maura decides to investigate the deserted coves and isolated inlets for herself. But this time she may be getting in over her head . . .

Release date: February 2, 2016

Publisher: Berkley

Print pages: 304

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

A Turn for the Bad

Sheila Connolly

Praise for the New York Times bestselling County Cork Mysteries

Berkley Prime Crime titles by Sheila Connolly

Title Page

Copyright

Acknowledgments

Epigraph

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Acknowledgments

Chapter 1

“John Tully’s gone missing.”

Maura Donovan looked up from behind the bar at the man who had burst into Sullivan’s, sending the door slamming into the wall. She didn’t recognize him, but then, she was still sorting out who was who around Leap, even after seven months in the village. The few customers in the pub, local men and regulars, didn’t seem to know what the latest arrival was talking about.

“What’re yeh sayin’?” one of them asked.

“John Tully,” the newcomer said, still out of breath. “Went out this mornin’ with his boy to take a walk on the shore, he told his wife. He hasn’t come back. No one’s seen him since. His brother went out to look fer him, found the boy wanderin’ on the beach. His wife’s beside herself with worry.”

“That’s bad,” another man said. “After that other thing and all.”

Maura was falling more and more behind in this conversation. If she’d got it right, not only had this Tully man disappeared, leaving a young child alone on the beach, but it had happened before? To Tully or to someone else? Nearby or somewhere else? She hadn’t heard anything about that, but for all she knew the first disappearance had happened a century earlier. She had learned that memories were long in this part of Ireland. “Is he from around here?” she ventured.

The first man turned to her. “Over toward Dromadoon. Sorry, we’ve not met. I’m Richard McCarthy, and you’d be Maura Donovan? Used to be I’d stop by now and then when Old Mick ran the place, but not lately.”

“I am,” Maura said, “and welcome back to Sullivan’s. So what’s happened?”

“John Tully, a good man, told his wife, Nuala, he wanted some air before the evenin’ milkin’. She told him to bring along the youngest child, Eoin, because she was takin’ the older ones to something or other. He did so. Nuala came back a few hours later, and there was no sign of man. It was gettin’ cold and she was worried about the little one, so she sent the brother Conor out to collect him. Conor comes back with the child, but not John. It isn’t like John to go missin’ like that. So she waited fer a bit, then went over to where John liked to walk. He had what he called a ‘thinking rock’ by the water, and she knew where to look. No sign of him there. She had the other kids with her, and Conor as well, so they all searched and they found nothing. Then she called the gardaí, and they’re searching now.” The man settled himself on a stool at the bar, and a couple of the other men took adjoining seats. “I could do with a pint, if you please.”

“Sure. Rose?” Maura nodded toward Rose Sweeney, who worked in the pub part of the time, as did her father, Jimmy, who’d been listening to the tale.

“Right away,” Rose said. “Anyone else?” Rose glanced around the room.

One of the other men at the bar nodded, and Rose started two pints.

Maura turned back to the men at the bar. “You said this has happened before? I mean, someone just disappearing?”

Richard McCarthy nodded, his expression somber. “Terrible thing, that was. Before your time, I’m guessin’, a year or two back. Older man, a farmer, married a young American who was visiting here, and they had a child, a little girl it was. Light of his life, he said. But the wife was talking about moving back to the States and takin’ the child with her. So the man went out with the girl while the wife was visitin’ a friend, and drowned the little one and then himself.”

“How awful!” Maura said. “Do you think John Tully . . .” Maura wasn’t sure how to finish her question. She didn’t know the man, but she couldn’t believe he would have taken his young child along if he planned to drown himself.

“God willing, I hope not. Nor is there any reason to suspect it. John’s a good man, and he and his wife get on well. He’d have no reason to do himself harm. And he loves the boy—the first son, after three girls.”

Rose slid the pints across the bar to the waiting men. “So who’s looking fer him now?”

“The neighbors and the gardaí. The wife’s waitin’ back home with the kids—she had the milkin’ to do. The gardaí haven’t called the coast guard yet, seein’ as there’s no reason to think he was out on the water. John has no boat and wasn’t much of a man fer the boatin’, him raisin’ cows and all. But he liked the walk—said it was good for his thinkin’. Ta.” He raised his glass to Maura. She realized she probably was expected not to charge him for it since he was the bearer of news, even if the news was bad. Another thing she was getting used to: the odd rules about who paid and when at the pub.

“Will they be needin’ help?” one of the other men asked.

“Might do. It’ll be gettin’ dark soon. No doubt the gardaí will get the word out if it’s wanted. And some of you must be volunteers for the coast guard, eh?” McCarthy had finished his pint quickly, draining the last of it. “I’m off to tell the folk at Sheahan’s across the street. Pray fer the man, will yeh?”

After McCarthy had left, the remaining men lapsed into glum silence. Maura checked the time: only a couple of hours until dusk, now that it was late October. Would that be enough time to search? She could understand how a man could walk out of his home and just keep going, but to take a small child along and then abandon him? That made no sense.

“Rose, I’m going to talk with Billy for a bit, okay?” Maura said.

“No worries. I think I can handle the crowd here,” Rose replied, dimpling. By Maura’s count there were five customers in the room, including Old Billy, who lived in a couple of rooms at the far end of the building that Maura now owned and who spent most of his waking time holding court in the pub, seated by the fire. She guessed he was well past eighty, but she wasn’t sure even he knew his age. He had known Maura’s predecessor Old Mick well, and luckily Billy Sheahan had stayed around to see Maura through the first few rocky months. And since he had lived in the area all of his eighty-plus years, he knew the history of most people and places in West Cork.

Maura walked over to the corner by the fire, where Billy occupied his favorite armchair—which no one else who knew the place dared to sit in—and sat down in the adjoining chair. “Are you ready for another pint, Billy?”

“Not yet, thanks fer askin’. McCarthy’s news has put me right off my drink.”

“It doesn’t sound good. Do you know the Tully family?” Maura asked.

“I knew John’s grandfather, years ago. They’ve a nice little piece of land over west of here, and they keep cows. The make a fair living at it, from what I hear.”

Maura thought a moment. “So you’re saying John Tully would have no reason to, well, do himself harm?”

“Not likely. And he and his wife are well suited, and they grew up together. And then there’s the child. The man was over the moon about havin’ a son at last, after the three girls.”

“That’s what I was thinking—he wouldn’t have just gone off and left the kid. So if John didn’t have any problems, where is he?”

“That I cannot say,” Billy replied somberly.

“What’s the coast guard like around here? I haven’t heard much about them. Well, except when a fishing boat goes missing or starts to sink.”

Billy smiled. “I’ll give yeh the short course, shall I? The Irish Coast Guard is a national organization that rescues people from danger at sea or on land, and that includes the cliffs and the beaches. There are three rescue centers, and the closest is on Valentia Island, over to Kerry. The Volunteer Coastal Units can do search and rescue—the nearest ones are at Glandore, and no doubt you’ve been past that one, and Toe Head. They’d be the ones would be called in fer this. They’re volunteers, local men and women alike, who have to live within ten minutes of the station—which clearly we here in Leap do—and they’re always on call.”

“I never knew any of that, Billy,” Maura said. “How come you know so much about it?”

“One of me nephews has been a volunteer fer years. But he’s seldom called in. Still, there are always those daft tourists who think climbing a cliff is a fine idea, until they get into trouble and they have to be rescued.”

“Richard McCarthy didn’t think they’d been called yet.”

“I knew the beach Tully likes, years ago, and I doubt it’s changed much. If the man isn’t found there, the rescue teams will be called in soon enough.”

“Was the coast guard part of that other story?”

“Where the little girl was drowned? They were, as were the gardaí and the local firemen. But neither father nor daughter was found until the next day. The man left a note behind, although it took them a bit to find it.”

“And no one saw them go into the water?” Maura asked.

Billy looked at her. “You’ve not spent much time along the beaches here, have you, now? There’s few people near enough to see anything, if they’re not lookin’ fer it.”

“I haven’t had the time, I guess, and I don’t much like just going for walks. Down along the harbor here now and then, but that’s about it.”

“Did you not grow up near the sea?”

“Well, yes and no. Boston’s got a harbor, and there’s plenty of coastline nearby, but I never had the time to go off and look at the water and play in the sand. I was usually working at one job or another, when I wasn’t in school.” There had always been a job, because she and her gran had never had enough money.

“Do yeh know how to swim?” Billy asked.

“Enough to stay afloat, Billy. My high school got some kind of special grant to give the kids swimming lessons. That’s about it. Doesn’t mean I like it.”

“There’s many a fisherman hereabouts who can’t swim, so yer ahead of the game there.” The front door opened, and Billy nodded toward the newcomers. “You’ve business to tend to. Maybe there’s someone who’s had some good news.”

“Let’s hope so, Billy.” Maura went back to her usual place behind the bar and started helping Rose pull pints for the newcomers. It didn’t surprise her that the crowd grew throughout the evening, everyone hoping to hear that John Tully had been found. Most of the people who came in knew him, or had bought cows or milk from him, or were related to his mother’s cousin over near Clonakilty, and so on. Maura had given up trying to sort out all the invisible connections that existed in this part of Ireland, or maybe throughout the entire country—she hadn’t had time to check out more than this small corner.

Mick Nolan, the final member of Maura’s staff, had arrived around five and kept busy since. Maura hadn’t had time to ask if he had come out of concern for John Tully or because he had heard the news and guessed that it would be a busy night at the pub. As the night wore on, Maura noticed a current of anxiety running through the crowd. No one was drinking much, and Maura hadn’t the heart to insist that they keep buying pints. Mostly the people there wanted to be together, either to wait for whatever news came or to share the outcome, good or bad.

It was past ten when garda Sean Murphy walked in. Conversation in the pub came to a halt, and all eyes turned toward Sean. He came straight to the point.

“No sign of the man. They’ve called off the search until first light.”

The mood in the room ratcheted down a notch, and people started draining their glasses and heading for the door: there would be no more news this night. Sean made his way to the bar.

“A pint or coffee?” Maura asked.

Sean rubbed his face. He looked tired, despite the fact that he was younger than Maura’s twenty-five years. “I’d love a pint, but it’ll be an early day tomorrow. Coffee, if you will.”

“Coming up,” Maura said.

“I’ll do it,” Rose volunteered. Maura hadn’t even noticed she was still there, they’d been so busy. Rose usually left early in the evening, except weekends, but most likely she had been as anxious as the rest of the people to hear what was going on.

Maura leaned on the counter to ask Sean, “What can you tell me?”

Sean shook his head. “Too little. Everyone’s been out hunting half the day, since we heard. The mother’s been hovering at the scene, with some of her family around her. The children are staying with the rest of ’em.”

“Where’d you find the boy? You must have gone over that beach with a fine-tooth comb. Did you find anything useful?” Maura asked, although she wasn’t sure what that might be.

Sean glanced around, but no one was near enough to overhear their quiet conversation. “We found some footprints where Conor told us to look—large and small, together. But they were soon trampled by well-meaning people lookin’ fer the man.”

“I heard it was John’s brother who found the boy and took him home,” Maura said. “Is he old enough to tell you anything?”

Sean shrugged. “Hard to say. He’s only just turned three, and his mother’s barely let him get a word out since he’s come home. What he’ll remember in the morning is anyone’s guess. The best we got was that he kept talkin’ about a boat. No surprise, seein’ as how he was on the beach.”

“Did he seem upset? Did he mention his dad?” If the boy had seen a fight, what would he have made of it?

Sean almost smiled. “Maura, have I not just told you we don’t know the details yet? We’ll sort it out in the morning. The poor lad was exhausted, as was his mother. We’ll all have fresher eyes tomorrow.” He drained his cup quickly. “I’d better be on my way so I can get an early start. I only wanted to make sure you knew the story so far, and the others here, so they could spread the word.”

“Thank you, Sean. I appreciate it,” Maura said softly. Maura wasn’t quite sure whether he had been thinking of her concern or only wanted to get the word out as quickly as possible—and what better way than to tell a pub full of worried people? “Safe home.”

“And to you,” Sean said, then gathered himself up and went out the door.

The crowd cleared quickly after that, and by midnight only Maura and Mick remained, clearing up the last of the glasses scattered around the room.

“Mick, are you planning to stop by your grandmother’s tomorrow?” Maura asked, washing the final glasses.

“I might do,” he said. “Why?”

“Could you stop by my house? I’ve got a small problem and I’m not sure what to do.” She hated to ask anyone for help, much less someone she worked with, but there were things she was clueless about, and how to manage an old stone cottage in this part of the world was one of them. She needed someone who knew how things worked, and she knew Mick was often down the lane visiting his grandmother Bridget.

“Glad to. I’ll look in before I see me gran.”

“Thanks, Mick. See you in the morning, then. And we should probably be here early, because people will want to hear the news about John Tully.”

“Troubling, that,” Mick commented. “Something’s not right. John would never have left his son like that.”

So what had happened? Maura asked herself. Tomorrow would tell. She hoped.

Chapter 2

Maura woke early the next morning but delayed getting out of bed. The room was cold. Heck, the whole house was cold. That was why she had reluctantly asked Mick to come by. She had grown up mainly in triple-deckers in South Boston, where somebody else was responsible for providing heat. Even when some crummy landlord failed to do that, it was still out of the tenants’ hands to fix. But here? Even if she had known what to do back in Boston, an old cottage in Ireland was another story altogether. She’d inherited it from Mick Sullivan, who had been related somehow to her grandmother, and he’d also left her the pub, free and clear. But nobody had left instructions for either. She’d moved in back in March, and between blankets and sweaters she’d managed to stay warm enough then until the weather had warmed up—as much as it ever did. She thought she’d toughened up, but now that the days were short and whatever heat had built up in the old stone and stucco walls had gone away, it was cold inside. And it would get colder.

She finally threw off the bedcovers and pulled on socks and two layers of shirts, with a sweatshirt over, then plunged down the stairs to boil water for tea or coffee—she ought to offer Mick something. He’d seen her house back when Old Mick had lived here, but had he been inside since she had taken over? She couldn’t remember. Not that she’d changed much. Mick had lived simply. She’d kept the large scarred and scrubbed table in the middle of the big kitchen room, and the chairs around it, but apart from that there was little in the way of furniture. Old Mick Sullivan had spent his last days in a ratty bed in the adjoining parlor, and she’d gotten rid of that, but otherwise there were only a couple of tired-looking upholstered chairs in that room. Apparently Old Mick hadn’t done too much entertaining—maybe like her he’d spent most of his waking hours at the pub. She’d bought herself a new bed for one of the bedrooms upstairs, but that was about the full extent of her redecorating. She hadn’t even bothered with curtains, since none of the neighbors was close enough to see into her windows.

The water had barely boiled when someone rapped at her front door, and she opened it to find Mick Nolan standing outside. “Come in,” she said, then shut the door quickly behind him. “You want tea? Coffee?”

“I’m sure tea will do fer me. What was it you wanted to ask?”

“It’s freezing in here,” Maura said, trying not to sound whiny.

“That it is,” Mick agreed. “So?”

“I don’t know how to heat this place. What do I do?”

Mick stared at her for a moment, then laughed. “Sure and there’s no fancy thermostat to turn on, is there?”

“I didn’t expect that,” she said tartly. “But there’s got to be something, right?”

“Well, fer a start, you’ve the two fireplaces.”

“Yeah, I can see that. The one in this room here scares me—I could roast an ox in it, not that I’ve ever wanted to roast an ox. Still, it’s huge. The other one’s not much use because I keep that room closed most of the time, and the fireplace is smaller anyway—wouldn’t heat the whole downstairs, would it? But how am I supposed to know if the chimney or whatever for the big one doesn’t have a family of birds nesting in it, or worse? Is there some kind of flue I’m supposed to open?”

“That’s easy enough to check,” Mick said.

Easy for you to say. “Sure, if you know what you’re looking for. And if it’s clear, what the heck do I burn in it?”

Mick appeared to be enjoying himself, Maura noted. “In the old days,” he began, “which were not that long ago, you’d have a piece of bog land, where you’d cut your own turf.”

“Yeah, right. Like I’m going to start doing that, even if I do have that piece of land. And isn’t peat kind of wet? How the heck do you make it burn?”

“Not many do, anymore, although there’s power plants that run off turf, sort of a combination of the old and the new. And yer right—you have to harvest the turf well ahead of time and stack it to dry, before you can hope to use it.”

“Little late to hear that, isn’t it? I’m going to make a cup of something hot, because I’m getting colder by the minute standing here and listening to you give me the history of heating in Ireland.” Maura stalked over to the stove—which she had managed to make work—and poured the water she had boiled into a metal teapot (inherited from Old Mick, along with the mismatched plates and cups) and threw in a couple of tea bags.

“Fair enough. You’ve the fireplace, and you can buy fuel at most petrol stations around here. You have yer choice of wood, coal, or turf. Or some mix of them.”

“Okay, that’s progress. Is one better than another?”

“Turf doesn’t give off much heat. Wood and coal are better. But you’ve another option as well.”

“Which is?” Maura stuck a spoon in the teapot, swirled the tea bags around, then poured one mug for Mick, then one for herself, to which she added sugar. She handed Mick his, then clutched her own with both hands.

Mick nodded toward the stove. “There’s yer heat.”

“Huh?” Maura knew that in the poorer areas of Boston, people had been known to turn on the oven and leave the door open, assuming the gas and power were still connected, but she didn’t think that applied here.

“Did you not wonder what those other dials were for?”

“Uh, no. I don’t do much cooking. I’ve figured out how to turn on the burners and the oven, but that’s about it.”

“The other side’s the heat. At least fer this room, and if you leave the door between open, the other down here. Mick never thought it was important to heat the upstairs rooms beyond whatever heat made its way up there. He had few overnight guests, as you might guess.”

“Okay,” Maura said dubiously, looking at the hulking stove in the corner next to the immense fireplace. “So why isn’t it warm?”

“Fer a start, you’ve not turned it on. And probably the oil tank’s dry. Mick only bought as much as he thought he needed.”

“I have an oil tank?” Maura asked.

“You do, out back.”

Great. Now she felt doubly stupid. “And how do I fill that?”

“I can give you the number of an oil service. You can talk to them about how much you might need fer the winter—they know this type of building well.”

“Is that what Bridget’s using?”

“Much the same. I see that her tank’s topped up. But I don’t fill it—there are those who are down and out who think nothing of siphoning off a bit, even from an old woman.”

“That’s a shame. Does my tank have a lock?”

“It might do—I haven’t looked at it lately. But odds are anyone who was set on getting into it could do it easily enough. Was there anything else you needed to know? Plumbing? Wiring?”

“Well, so far I’ve got light and hot water, and I’ve been billed for the power. The lawyer who helped me out with Mick’s will set that much up for me.”

“And you’ve a well for water, so no water rates. It’s really a simple system, you know.”

Maura sighed. “I figured it was, but I’m not mechanical. And as I’m sure you’ve noticed, I don’t spend a lot of time here, particularly by daylight, so I usually don’t think about it. Thanks for explaining things.”

“No problem. I’ll go pop in on Bridget now.”

“Does she know about John Tully?”

“I’d guess her friends have told her by now. She won’t admit it to me, but she spends a fair amount of time on the phone chatting with them.”

“Does she know the Tully family? Or is she related to them in any way? Because most of the people around here seem to be connected somehow.”

“Not that I recall. She’ll be rememberin’ that last time, though.”

“That was really sad. I can’t understand any man killing his own child—that’s not right.” Was there something about the isolation of the Irish countryside and the endless hard work of running a farm that caused depression severe enough to lead to something like that? She hoped not. The man had had a wife, and from what Maura had seen, people looked out for each other around here.

“It was that. But by all accounts, this is different. John’s a steady man, and he loved that boy—well, all the children, and the wife as well. The farm was doing well. Maybe the child will shed some light on it.”

“The kid’s three!” Maura protested. “What could he know?”

“Have you no memories from that time of your life?”

“Only patchy ones. I wish I had known my parents, but my father died not long after I was born, and my mother dumped me on my grandmother and disappeared. My grandmother assumed from the start that my mother, Helen, was not cut out for motherhood. Or working.”

“You’ve never tried to find her?” Mick asked.

“What for? She made her choice. And until Gran died, she knew where to find us, if she wanted to, because we never moved. Anyway, you can’t miss what you’ve never known. She’s never been real to me.”

“I’m sorry,” Mick said quietly. “It must have been a hard life fer yeh.”

She shrugged. How had the conversation drifted from heating the building to her parents? “I guess I’m not a good example for a happy family. But if the boy saw something upsetting, wouldn’t it make an impression on him?”

“Maybe, but you can’t have the gardaí and the rescue folk swoop down on the poor boy and throw questions at him. I only hope that his mother’s not so hysterical that she doesn’t listen to what he might say.”

Maura found herself wondering if Sean could connect with him. Sean was relatively young and, more important, he had a kind of unselfconscious innocence that might be less threatening to a child.

As if reading her mind, Mick said, “Yer man Sean might be a good man to talk to him.”

Maura bristled. “He’s not ‘mine.’”

“I’m thinkin’ he might like to be.”

Suddenly the room seemed smaller to Maura, and she realized how rarely she was alone with Mick. And there had been that one kiss, not so long before . . .

“He’s a friend. That’s all.” Maura tried hard not to sound defensive. She didn’t owe Mick Nolan any explanations.

Mick gave her a long look, but his only response was, “I’d best be getting over to me gran’s. Want me to open at the pub?”

“You take your time with Bridget. I might as well go in early—it’s usually warmer there. Maybe there’ll be some word about John Tully.”

“God willing. See you later, then.”

“Thanks, Mick.”

Maura shut the door behind him. So her stove was also her heat source? She’d never heard of such an arrangement, but it made sense. Too bad

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...