ONE

August 27, 1940

ELEVEN DAYS EARLIER

If I had to look at one more tray of anti-tank shells, I was going to scream. A full-throated, head-thrown-back, ear-piercing bloody scream.

Now, I’ll admit that this threat was more metaphorical than literal; however, I am my mother’s daughter and Maman was predisposed to the occasional display of dramatics.

Gripping the workbench in front of me with both hands, I took one or two of the deep meditative breaths my dearest friend, Moira, swore by and reviewed the facts at hand.

One: I was nearly done with my shift at the royal ordnance factory.

Two: Mrs. Jenkins expected me to pay my usual rent at the end of the week.

Three: There was a war on.

Taking all of these factors into consideration, I had to admit that it would be neither prudent nor patriotic to find myself sacked. We were all supposed to be doing our bit in the war against Nazi Germany. I just wished my bit wasn’t quite so mind-numbingly dull.

The trouble, I reasoned as the huge factory clock mounted to the far wall ticked slowly closer to the end of my shift, was that almost anyone could fill racks of half-empty shells with powder to the same precise measurements every time, ensuring that the shell detonated as expected and blew up its target. I’d mastered that challenge in my first half day on the job six months ago, and even Sheryl four down the row from me was coping while nursing a head sore from a night’s drinking at the pub around the corner from the factory.

Somehow I managed to last forty-one more minutes without running amok on the factory floor, and when the shift change bell rang I pushed away from my table, nearly elbowing my fellow lady workers out of the way in our daily sprint to the changing rooms.

Munitions is a messy, dangerous line of work, so we all wore stiff boiler suits, tight turbans, and steel-toed shoes, and we were checked every time we came onto the factory floor. One errant hairpin could cause a spark and blow the entire place to kingdom come. The changing rooms at a royal ordnance factory, therefore, are a magical place of transformation where women morphed from canvas-covered caterpillars into cotton, linen, and even silk-clad butterflies.

Even though it was only Tuesday, my colleagues were already making plans for the weekend while they dressed. I’d tagged along to a couple of dances when I’d started back in February, but I’d quickly lost my taste for nights out where the ratio of men to women would be woefully skewed by conscription. It wasn’t any fun dancing a foxtrot with another girl when we both kept forgetting who was meant to lead and who to follow.

At my locker, I gave a few polite nods and demurred when several women next to me asked where I was off to in such a hurry. Maman had taught me at an early age that, whether they be male or female, it was best to cultivate an air of mystery by leaving a curious audience wondering.

The reality was that my plans for that evening were no more ambitious than to curl up with the brand-new copy of Death at the Bar by Ngaio Marsh I had picked up on my way into work from the news agent around the corner from the factory. You see, I simply adore detective fiction. Each new story contains within it the tantalizing possibility of a puzzle so fiendishly twisted that the solution may elude me until the final pages.

I began reading detective fiction at sixteen. Finally allowed into the village my school was nestled in, I’d taken the meager allowance Aunt Amelia bestowed on me out of pity and purchased a subscription to the local lending library. It was really just two bookcases angled toward each other in the corner of the shop that served as post office, news agent, and sweets counter, but to me it represented a world of literary possibility. At first, I tried a little bit of Dickens, some Wolfe, and even a romantic novel or two. They were all well and good, but it was a beaten-up copy of The Mystery of the Blue Train by Agatha Christie that I could not put down. I read it so quickly I was left with days to wait until I could return to the village and change it for another. I checked the publication dates of the few Christie copies on the shelves and was delighted to return to the beginning of Monsieur Poirot’s stories with The Mysterious Affair at Styles.

Now, at twenty-two and with years of reading under my belt, it was rare that an author could stump me—the great exception being Christie, who had shocked me with the dastardly twist at the end of Murder on the Orient Express—but I relished the hunt for a fictional killer, nonetheless.

At my locker, I finished pulling on my wide-legged tan trousers and cream shirt. On went Maman’s gold watch and her pearl earrings. Unwrapping the cotton turban that kept my hair out of my face while I worked, I shook out my dark brown curls and settled my tan beret at an angle on the crown of my head. Even on my best day, I would never draw attention away from Moira when we stood side by side, but I had a certain flair that could attract the occasional appreciative nod from a passing soldier. Not that I was particularly interested.

I waved goodbye to my fellow munitions ladies, sending Sheryl and her sore head a sympathetic nod, and let myself out of the factory door. This, I decided, was a lucky day because the bus was on the corner and the driver—a fellow woman doing her part to “free up a man for the force”—waited while I sprinted up on my short brown heels. I gave my money to the ticket collector and settled into a seat in the back corner, where I knew I wouldn’t be disturbed.

I was twenty pages into my book when the driver called out my stop. I pulled the cord and clambered up and out onto the pavement down the road from my digs.

I lived in a tall redbrick building that would be unremarkable to any passerby unless they were to glimpse inside. Then, they would be assaulted by a wall of giggles and the occasional shriek, as well as the constant, comforting scent of laundry. Mrs. Jenkins, who lived on the ground floor and reigned over the sitting room, kitchen, and dining room, had split up the other three floors into rooms to let sometime after the last war. Installed into these six rooms were twelve young women, including myself.

When I’d moved in, Mrs. Jenkins had told me that she only let rooms to respectable ladies. However, I’d soon learned that respectability was not the only requirement for living in digs with Mrs. Jenkins. A woman needed the ability to merrily bump along while crammed into a rickety, madcap building. Being able to sleep through all manner of snores, shouts, and other noises also helped.

Moira and I had a room two flights of stairs up, across from Cynthia, a secretary working a mysterious job in Whitehall she rarely spoke about, and Jocelyn, a model-turned-journalist whom Moira had met on a photo shoot and recruited for the house just before this beastly war kicked off. Moira had promised Cynthia and me that Jocelyn would be a vast improvement on Cynthia’s previous roommate, Sally, a postal worker who spent nearly an hour in the bath each morning if you didn’t pound on the door and demand your fair share of the hot water. So far, Moira had been proven right. Jocelyn worked such long hours on Fleet Street that we hardly saw her.

That evening, I climbed the stairs with my book in front of my face, pausing only to sweep up a set of stockings hanging from the banister in front of my room. I twisted the doorknob, pushed inside, and found Moira on the edge of her bed, leaning out the window with a cigarette in her hand.

“I wish you wouldn’t do that, darling,” I said as she hastily hid her cigarette around the edge of the blackout curtains, only to bring it out again when she realized it was just me.

She pulled a face. “I can’t very well run down to the road every time I want a smoke.”

“You’re going to land both of us in trouble,” I said, letting my gas mask holder slide off my shoulder and drop in a heap on a chair along with my brown leather handbag. They nearly knocked a stack of paperbacks to the floor, but I managed to catch the pile with my foot and right it just in time.

“I’ll swear to Mrs. Jenkins that you never smoke,” said Moira.

“And the stockings?” I tossed them at her. “She thinks it lowers the tone of the place when you leave them out to dry.”

“I only do that because it’s so bloody damp in this room that nothing dries. Even in August,” said Moira, plucking the stockings out of the air before they could drift down to the carpet.

I flopped on the bed, my book on my chest, but didn’t open it. “How was your day?”

Moira sighed. “Ghastly. It was another one of those awful dumb doll parts again.”

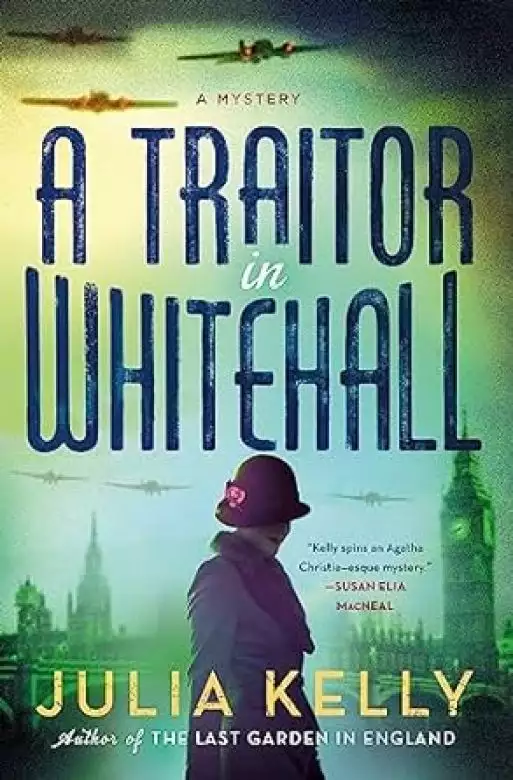

Copyright © 2023 by Julia Kelly

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved