- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

The Royal Society of London plays home to the greatest minds of England. It has revolutionized philosophy and scientific knowledge. Its fellows map out the laws of the natural world, disproving ancient superstition and ushering in an age of enlightenment.

To the fae of the Onyx Court, living in a secret city below London, these scientific developments are less than welcome. Magic is losing its place in the world-and science threatens to expose the court to hostile eyes.

In 1666, a Great Fire burned four-fifths of London to the ground. The calamity was caused by a great Dragon—an elemental beast of flame. Incapable of destroying something so powerful, the fae of London banished it to a comet moments before the comet’s light disappeared from the sky. Now the calculations of Sir Edmond Halley have predicted its return in 1759.

So begins their race against time. Soon the Dragon’s gaze will fall upon London and it will return to the city it ravaged once before. The fae will have to answer the question that defeated them a century before: How can they kill a being more powerful than all their magic combined? It will take both magic and science to save London-but reconciling the two carries its own danger …

Release date: August 31, 2010

Publisher: Tom Doherty Associates

Print pages: 496

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

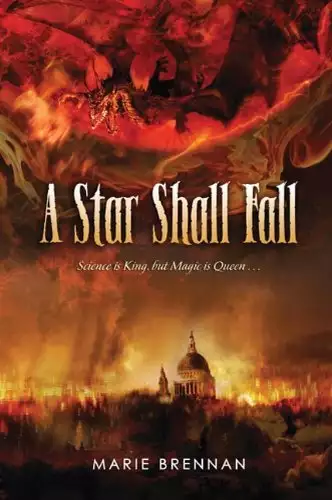

A Star Shall Fall

Marie Brennan

PART ONE

CongelatioAutumn 1757

Purged by the sword and beautified by fire,

Then had we seen proud London's hated walls.

—Thomas Gray,

"On Lord Holland's Seat near M——e, Kent"

The blackness is spangled with a million points of light. Stars, galaxies, nebulae: wonders of the heavens, moving through their eternal dance.

Far in the distance—impossibly far—a bright spark burns. One sun among many, it calls the tune to which its subjects dance, in accordance with the immutable law of gravity. Planets and their follower moons, and the brief visitors men call comets.

One such visitor draws near.

The oblong is frozen harder than winter itself. The sun is yet distant, too distant to awaken it to life; the light barely even gilds the black substance facing it. The spirit that dwells within the comet sleeps, driven into torpor by the endless cold of space.

It has slept for more than seventy years. The time will soon come, though, when that sleep will end, and when it does . . .

The beast will seek its prey.

Mayfair, Westminster: September 30, 1757

The sedan chair left the City by way of Ludgate, weaving through the clamor of Fleet Street and the Strand before escaping into the quieter reaches of Westminster. A persistent drizzle had been falling all day, which the chair-men disregarded, except to choose their footing carefully in the ever-present slime of mud and less savory things. The curtains of the chair were drawn, blocking out the dismal sight, and the twilight falling earlier than usual.

Inside, the blackness and rhythmic swaying were almost enough to put Galen to sleep. He stifled a yawn as if his father were watching: Up late carousing, no doubt, the old man would say, gambling your allowance away at Vauxhall. As if he had much of an allowance to wager, or any inclination to such pursuits. But that was the simplest explanation for Galen's late nights and frequent absences, and so he let his father go on believing it.

Regardless, he would do well to rouse himself. Galen had visited Clarges Street before, but this would be his first formal gathering there, and yawning in his fellow guests' faces would not make a good impression.

A muffled cry from one of the chair-men as they slowed. Then the conveyance tilted, rocking perilously up a set of stairs. Galen pulled the curtain aside just in time to see his chair pass through the front door of the house, into the entrance hall, and out of the rain.

He stepped free carefully, ducking his head to avoid knocking his hat askew. A footman stood at the ready; Galen gave his name, and tried not to fidget as the servant departed. Waiting here, while the chair dripped onto the patterned marble, made him feel terribly self-conscious, as if he were a tradesman come to beg a favor, rather than an invited guest. Fortunately, the footman returned promptly and bowed. "You are very welcome, sir. If I may?"

Galen paid the chair-men and surrendered his cloak, hat, and walking stick to the footman. Then, taking a deep breath, he followed the man to the sitting room.

"Mr. St. Clair!" Elizabeth Vesey rose from her seat and crossed to him, extending one slender hand. He bowed over it with his best grace, lips brushing lightly. Just enough to make her blush prettily; it was a game, of course, but one she never tired of, though she would not see forty again. "You are very welcome, sir. I feared this dreadful rain would keep you home."

"Not at all," Galen said. "My journey here was warmed by the thought of your company, and I shall carry the memory of it home like a flame."

Mrs. Vesey laughed, a lilting sound that matched her Irish accent. "Oh, well done, Mr. St. Clair—well done indeed. Do you not agree, Lizzy?"

That was addressed to a taller, more robust woman, one of at least a dozen scattered about the room. Elizabeth Montagu raised one eyebrow and said, "Well spoken, at least—but my dear, have you not instructed him in the proper dress for these occasions?"

Galen flushed, faltering. Mrs. Vesey looked him over from his ribbon-bound wig to the polished buckles of his shoes, and tsked sadly. "Indeed, sir, we have a very strict code for our gatherings, as I have told you most clearly. Only blue stockings will do!"

He looked down in startlement at his stockings of black silk, and tension gave way to a relieved laugh. "My humblest apologies, Mrs. Vesey, Mrs. Montagu. Blue worsted, as you instructed. I will endeavour to remember."

Linking her arm through his, Mrs. Vesey said, "See that you do! You are far too stiff, Mr. St. Clair, especially for one so young. You mustn't take us too seriously, or our little Bluestocking Circle. We're merely friends here, come together to share ideas and art. Dress as if for court, and you'll put us all to shame!"

There was some truth to her words. Not that he was dressed for court; no, his gray velvet was far too somber for any occasion so fine, though he was very pleased with the new waistcoat Cynthia had given him. But it was true that few of the people present showed anything like such elegance, and in fact one of the two gentlemen present might have been a tradesman, dressed for a day of work.

Galen let Mrs. Vesey conduct him about the room, making introductions. Some he'd met before, but he appreciated her reminders; he always feared he would forget a name. The two gentlemen were new to him. The seeming tradesman was one Benjamin Stillingfleet—who, true to Mrs. Vesey's word, was wearing ordinary blue stockings—and the other, a stout and loud-voiced figure, was revealed to be the great Dr. Samuel Johnson.

"I am honored, sir," Galen said, and swept him a bow.

"Of course you are," Johnson grunted. "Can't go anywhere in this town without being known. Damned nuisance." His head jerked oddly on his shoulders, and Galen's eyes widened.

"If you did not want recognition," Mrs. Montagu said tartly, "you should not have poured years of your life into that dictionary of yours." She took no notice of the gesture, nor of his ill manner, and Galen thought it best to follow her example.

Mrs. Vesey's drawing room was a masterpiece of restrained elegance, its chairs upholstered in Chinese silks that showed to great advantage in the warm glow of the candles. It lacked the ruelles and other accoutrements of the great salons in Paris, but this was a modest affair after all; scarcely more than a dozen guests altogether. Mrs. Montagu hosted much larger gatherings at her own house on Hill Street, and she was nothing to the French salonnières. Galen was glad of the smallness, though. Here he could believe, as Mrs. Vesey said, that he was among friends, and not feel so conscious of himself.

As he retired to a chair with a glass of punch, Johnson picked up the thread of a conversation apparently dropped when Galen entered the room. "Yes, I know I said March," he told Stillingfleet impatiently, "but the work takes longer than expected—and there's another project besides, a series called The Idler, which will begin next month. Tonson can wait." His manner as he spoke was most peculiar—more strange tics of the head and hands. It was not a palsy, but something else altogether. Galen was torn between staring and looking away.

"Shakespeare," Mrs. Vesey murmured to Galen, not quite sotto voce. "Dr. Johnson is working on a new edition of the plays, but I fear his enthusiasm fades."

Johnson heard her, as she no doubt meant him to. "To do the work properly," he said with dignity, "takes time."

Mrs. Montagu laughed. "But you don't dispute the lack of enthusiasm, I see. What play is it you edit now?"

"A Midsummer Night's Dream, and a piece of nonsense it is, too," Johnson said. "Low comedy—quite unappealing, to discerning tastes—full of flower faeries and other silliness. What moral lesson are we to derive from them? Do not tell me he wrote of pagan times; it is a writer's duty to make the world better, and—"

"And justice is a virtue independent of time or place," Mrs. Montagu finished for him. "So you have said before. But must there be a lesson in faeries?"

The writer's eyebrows drew together sharply. "There can be no excuse for them," Johnson said, "if they serve not a moral purpose."

Galen found himself on his feet again, with no sense of transition, and his glass of punch clutched so tightly in his hand he feared the delicate glass would shatter. "Why, sir, you might as well say there can be no excuse for a tree, or a sunset, or a—a human, if they serve not a moral purpose!"

Johnson's white eyebrows rose. "Indeed there is not. The moral purpose of a human is to struggle against sin and seek out God, to redeem himself from the Fall. As for trees and sunsets, may I refer you to the Holy Bible, most particularly the Book of Genesis, wherein it tells us how the Lord created the day and the night—and therefore, we may presume, the transition between them—and also trees; and these are the stage upon which He put His most beloved creation, which is that human previously mentioned. But show to me, if you will, where the Bible speaks of faeries, and their place in God's plan."

While Galen sputtered, searching for words, he added—almost gently—"If, indeed, such creatures exist at all, which I find doubtful in the extreme."

Heat and chill washed Galen's body in alternating waves, so that he trembled like a leaf in the wind. "Not all things," he managed, "that exist in the world, are laid out in scripture. But how can anything be that is not a part of God's plan?"

Somehow Johnson managed to convey both disgust and delight, as if appalled at the triviality of the topic, but pleased that Galen had mustered an argument in its defense. "Just so. Even the very devils in Hell serve His plan, by tempting mankind to his baser nature, and therefore rendering meaningful the exercise of his free will. But if you wish to persuade me regarding faeries, Mr. St. Clair, you will have to do better than to hide behind divine ineffability."

He wished for something to hide behind. Johnson had the air of a hunter merely waiting for the pheasant to break cover, so he could shoot it down. Oh, if only this debate had not come so soon! Galen was new to the Bluestocking Circle; he scarcely had his feet under him. Given more time and confidence, he would have defended his ideals without fear of ridicule. But here he was, a newcomer facing a man twice his age and twice his size, with all the weight of learning and reputation on Dr. Johnson's side.

To flee would only invite contempt, though. Galen was aware of his audience—not just Johnson, but Mrs. Vesey and Mrs. Montagu, Mr. Stillingfleet, and all the other ladies, waiting with great enjoyment for his next move. And others, not present, who deserved his best attempt. Choosing his words carefully, Galen said, "I would say that faeries exist to bring a sense of wonder and beauty into life, that lifts the spirit and teaches it something of transcendence."

"Transcendence!" Johnson barked a laugh. "From something called Mustardseed?"

"There is also Titania," Galen countered, flushing. "Faeries must have their lower classes as well, just as our own society has its farmers and sailors, tradesmen and laborers, without whom the gentry and nobility would have no legs to stand upon."

Johnson snorted. "So they must—if they existed at all. But this has been nothing more than a pretty exercise of the intellect, Mr. St. Clair. Faeries live only in peasant superstition and the inferior works of Shakespeare, where their only purpose is silly diversion."

Mrs. Montagu saved him. Galen didn't know what words would have leapt from his mouth had she not spoken, but the lady brought up Macbeth, and diverted Dr. Johnson onto the topic of witches, where he was only too happy to go.

Freed from the transfixion of the great writer's gaze, Galen sagged weakly back onto his chair. Sweat stood out on his brow, until he blotted it dry with a handkerchief. Under the guise of replenishing his punch—for these informal evenings, there was nothing stronger to drink, nor any servants to fill the glasses—he went to the side table, away from watching eyes.

But not away from Mrs. Vesey, who followed him. "I am so sorry, Mr. St. Clair," she murmured, this time taking care not to be overheard. "He is a very great man, but also a very great windbag."

"I came so near to saying too much," he told her, hearing the anguish in his own voice. "It would be so easy to prove him wrong—"

"On one count, perhaps," Mrs. Vesey said. "He will argue moral purposes until they nail his coffin shut, and then go up to Heaven to argue some more. But you would never betray that secret—no more than would I."

Even to say that much was dangerous. Of those gathered in this room, only they two knew the truth. Perhaps in time, a few others could be trusted with it; indeed, that was why Galen had come here, to see if any might. Instead he found Dr. Johnson, who made Galen long to blurt out the words burning within his heart.

There are faeries in the world, sir, more terrible and glorious than you can conceive, and I can show them to you—for they live among us here in London.

Oh, the fierce joy of being able to fling it in the other man's teeth—but it would do no good. Dr. Johnson would think him deranged, and though seeing would convince him, it would also be an unconscionable betrayal of trust. Faerie-kind lived hidden for a reason. Christian faith such as the writer showed could wound them deeply, as could iron, and other things of the mortal world.

Galen sighed and set down his glass, turning to glance over his shoulder at the rest of the room. "I had hoped to find congenial minds here. Not men like him."

Mrs. Vesey laid her hand on his velvet-clad arm. Sylph, her friends called her, and in the gentle light of the candles she looked like one, as if no particle of matter weighed down her being. "Mr. St. Clair, you are letting your impatience run away with you. I promise you, such minds exist, and we shall speak with them in due time."

Time. She spoke of it with the placid trust of a woman who had survived her childbearing years, to whom God might grant another two or three decades of life. Mrs. Vesey attributed Galen's impatience to his youth, thinking it merely the headlong rush of a man scarcely twenty-one, who has not yet learned that all things must happen in their season.

She did not understand that a season would come, very soon, when all this tranquility might be destroyed.

But that was another secret he could not betray. Mrs. Vesey knew of faeries; one called on her every week for gossip. But she knew little of their history, the myriad of secret ways in which they touched the lives of mortal men, and she knew nothing of the threat that faced them.

Already it was 1757. With every passing day, the comet drew closer, bringing with it the Dragon of the Great Fire. And when that enemy returned, the ensuing battle might well spill over into the streets of mortal London.

He could not tell her that. Not while standing in this elegant room, surrounded by the beautiful luxuries of literature and conversation and chairs upholstered in Chinese silk. All he could do was search for allies: others who, like him, like Mrs. Vesey, could stand between the two worlds, and perhaps find a way to make them both safe.

Mrs. Vesey was watching him with concerned eyes, hand still on his elbow. He smiled at her with as much hope as he could muster, and said, "Then by all means, Mrs. Vesey, acquaint me with others here. I trust you will not steer me wrong."

Tyburn, Westminster: September 30, 1757

Irrith often claimed, with perfect honesty, to cherish the unmediated presence of nature. Sunlight and starlight, wind and snow, grass and the storied forests of England; these were, in her innermost heart, her home.

At moments like this, though, ankle-deep in cold mud and drizzling rain, she had to admit that nature also had its unpleasant face.

She wiped the draggled strands of her auburn hair from her eyes and squinted ahead through the darkness. That might be light on the horizon—not just the scattered glow of a candlelit house here and there, but the massed illumination of Westminster, and beyond it, the City of London itself.

Or she might be imagining it.

The sprite sighed and pulled her boot free of the sucking mud. She was a Berkshire faerie at heart; her home was the Vale, and though she'd spent some years in the city, she'd left it long ago—and for good reason. Yet it was so easy to forget when Tom Toggin showed up, with all his persuasive arguments. She could take over his return journey; let the hob spend time with his cousins in the rustic comforts of the Vale, and relieve her own boredom with the excitement of London. It sounded like such a fine idea when he said it, especially when he offered bribes.

Maybe he'd known what awaited her on the road. The rain started just after she left, and accompanied her all the way from Berkshire.

As she walked, Irrith entertained herself with a vision of stumbling onto some farmer's front step, drenched and pathetic, begging shelter from the night. The farmer would aid her, and in exchange she'd bless his family for nine generations—no, that was a bit much, for mere rain. Three generations, from him to his grandchildren. And they would tell tales for the remaining six, of the faerie traveler their ancestor had saved, of how magic had touched their lives for one brief night.

Irrith sighed. More like the farmwife would screech and call her "devil." Or they would stare at her, the whole farm family of them, wondering what strange creature had come to their door, and what she could possibly want from them.

She knew she was being unfair. Country folk had not forgotten the fae; the burden she carried was proof of that. But whether Westminster was on the horizon or not, she was nearing the city, and she didn't have much faith in their knowledge of their proper duties toward faerie-kind.

How long had it been, since she last saw London? Irrith tried to count, then gave up. The time didn't matter. Mortals changed so rapidly, especially in the city; whether she was gone for six months or six years, they were sure to have invented strange new fashions in her absence.

She hitched the sack Tom had given her higher on one shoulder. Yes, those were definitely lights ahead, and something looming in the center of the road. Could that possibly be the Tyburn gallows? The triangular frame looked familiar, but she didn't remember there being so many houses near it. Ash and Thorn, how big had the city grown?

A rustle in the hedgerow to her left was her only warning.

Irrith dove flat against the mud as a black shape burst toward her. Its leap carried it clear over, so that it skidded and went down in the muck. A black dog, she saw as she scrambled to her feet. And not an ordinary hound, someone's mastiff escaped from its keeper; this was a padfoot or skriker, a faerie in the shape of a dog.

And he was not there to welcome her back to London.

The dog lunged forward, and Irrith dodged. But she realized her mistake as she went: the beast wasn't aiming for her. His jaws closed around the oiled cloth of the satchel she carried, and dragged it free of the mud.

Irrith snarled. Her blossoming fear died beneath the boot of fury; she had not hauled that bag all the way from Berkshire in the rain just to lose it to a padfoot. She threw herself forward and landed half on the creature's back. His feet splayed under the unexpected weight, and down they both went, into the mud again. Irrith grabbed an ear and yanked mercilessly. The black dog snarled and tried to bite her; but she was on his back, and now he'd lost the bag. The sprite snatched at the strap, and quite by accident managed to kick her opponent in the head as she slid across the ground. He shook his head with a whimper, then lunged at her again, and this time she was flat on her back with no way to defend herself.

Just before the beast's massive jaws could close around her leg, a sound broke through the patter of the rain, that Irrith had never thought she would be grateful to hear: church bells.

The black dog howled and fell back, writhing. But the peals broke harmlessly over Irrith, and so she seized her advantage, and the bag; clutching it in her filthy hands, she aimed herself at the Tyburn gallows and ran.

By the time the bells stopped, she was well among the houses that now crowded the once rural road. Irrith slowed, panting for breath, feeling her heart pound. Would the dog track her here? She doubted it; too much risk of someone hearing the disturbance and coming out to investigate. And now the other faerie knew she was protected, as he was not.

Then again, Irrith would have said if asked that no local faerie would dream of assaulting a fellow on the road, so close to his Queen's domain. A mortal, perhaps, but not a sprite like her.

Perhaps he wasn't local. But then what was he doing on the Tyburn road, waiting for her to pass with the delivery from the Vale?

It was a good question. She knew the fae of London had their problems, but she might have underestimated them. How much had changed here, besides the landscape?

She hadn't thought to ask Tom Toggin. Unless she felt like walking all the way back to Berkshire—past the black dog who might still be hunting her—the only way to answer that question was to continue onward, and present herself, looking like a rat drowned in mud, to the Queen of the Onyx Court.

The Onyx Hall, London: September 30, 1757

The crowded and unfashionable environs of Newgate, in the central City of London, were an unlikely destination for a gentleman so late at night, but so long as Galen paid the chair-men, they had no reason to ask questions. With the rain finally ended, they deposited him at the front of a pawnbroker's, closed for the night, and went on their way. Once they were well out of sight, Galen tiptoed around the corner, trying and failing to protect the shoes and black silk stockings Mrs. Montagu had derided, into a narrow alley.

The door he sought stood in the back wall of the pawnbroker's, and if anyone noticed it—which they should not—they no doubt assumed it let into the cramped room where the shopkeeper stored wares he could not fit in the display out front. Instead, it admitted Galen to a tiny alcove barely large enough for him to squeeze into and still shut the door behind him. Standing in that stifling space, he murmured, "Downward," and felt the floor drop away.

It was a vertiginous feeling, no matter how often he experienced it. Galen always tensed, expecting a bruising impact, and he always touched down as lightly as a feather. He would have preferred a more ordinary staircase. But with that word, he shifted from the ordinary world into one that was anything but.

His feet settled onto a roundel of black marble, and cool light bloomed around him. The chamber in which he now stood was a lofty dome—nothing to the soaring heights of St. Paul's Cathedral, but it felt so after the confines of the alcove above. The walls formed slender ribs that seemed inadequate to the weight, and no doubt they were; something other than the architect's art kept the shadowed ceiling up.

It was far from the greatest wonder here.

Country folk still told tales of faerie realms hidden away in hollow hills, but few if any would expect to find one beneath the City of London. So far as Galen knew, the Onyx Hall was unique; nowhere else in Britain, or possibly in the entire world, did fae live so close with mortal kind. Yet here they had a palace that was a city unto itself, crowded with bedchambers and gardens, dancing halls and long galleries of art, all protected against the hostility of the world above. It was a mirror of that world, casting a strange and altered reflection, and one that only a select few could enter.

Galen sighed to see the muddy track he left behind as he stepped clear of the roundel. He knew that if he left the chamber and came back a minute later, he would find the dirt gone; there were unseen creatures here, more efficient than the most dedicated servant, who seemed to treat the slightest mess as a personal affront. Or they would if they had any sense of self; as Galen understood it, they had very few thoughts at all, scarcely more than the faerie lights that lined the delicate columns along the walls. Still, he wished for a boot-scraper on which to clean his feet, so he would not trail bits of mud around so miraculous a place.

No help for it. Galen was about to abandon his concerns and proceed, when a sudden swirl of air tugged at the hem of his cloak.

Another figure descended from the aperture in the ceiling, dropping swiftly before floating to a halt on the roundel. Galen's own muddy prints were obliterated by an enormous smear as the dripping and filthy figure shifted, slipped, and landed unceremoniously on his backside.

"Blood and Bone!" the figure swore, and the voice was far too high to be male. Galen leapt forward, reflexively offering his hand, and promptly ruined his glove when the newcomer took the assistance to rise.

That she was a faerie, he could be certain; the delicacy of her hand—if not her speech—made anything else unlikely. But he could discern little more; she seemed to have rolled in the mud for sport, though some of it had subsequently been washed off by the rain. Her hair, skin, and clothes were one indeterminate shade of brown, in which her eyes made a startling contrast. They held a hundred shades of green, shifting and dancing as no human irises would.

She in turn seemed quite startled by him. "You're human!" she said, peering at him through the dripping wreck of her hair.

What polite answer could a gentleman make to that? "Yes, I am," he said, and bent to pick up the satchel she had dropped.

The faerie snatched it from him, then grimaced. "Sorry. Someone has already tried to take this from me once tonight. I'd rather carry it myself, if you don't mind."

"Not at all," Galen said. Sighing in regret, he pulled off the ruined glove and the clean one both, dropping them to the floor. The unseen servants might as well take those, too, when they came to mop this up. "May I escort you to your chambers? This marble is treacherous for wet feet."

He thought she might be a sprite, under all that mud; she didn't carry herself with the courtly grace of an elfin lady. Slinging the bag over her shoulder, she sat down again—this time deliberately—and pulled off her dripping boots, followed by her stockings. The feet beneath were incongruously pale, and as delicate as her hands. She set them down on a clean patch of floor, then levered herself to her feet. "I'll drip," she said, making a futile effort to wring out the hem of her coat, "but it's better than nothing."

Her efforts with the coat revealed a pair of knee breeches beneath. Galen suppressed a murmur of shock. Fae viewed human customs, including notions of proper dress, as entertaining diversions they copied or ignored as they pleased. And he supposed knee breeches more practical in this weather; had she been wearing skirts, she would not have been able to move for all the sodden weight. "Still, please allow me. I would be a lout if I abandoned you in such a state."

The sprite took up her bag once more and sighed. "Not to my chambers; I don't believe I have any, unless Amadea's kept them for me all this time. But you can take me to see the Queen."

This time the murmur escaped him. "The Queen? But surely—this mud—and you—"

She drew herself up to her full height, which brought her muddy hair to the vicinity of his chin. "I am Dame Irrith of the Vale of the White Horse, knighted by the Queen herself for services to the Onyx Court, and I assure you—Lune will want to see me, mud and all."

The hour was late, but that scarcely mattered to the inhabitants of the Onyx Hall, for whom the presence or absence of the sun above made little difference. This, after all, was London's shadow: a subterranean faerie palace, conjured from the City itself, where neither sun nor moon ever shone.

Which meant, unfortunately, that people were around to see the unlikely progress of Irrith and the young man at her side. She carried herself defiantly, ignoring them all, and telling herself it wouldn't help much if she did go in search of a bath first; given the tangled layout of the Onyx Hall, she would pass as many folk on her way there as she would going to see the Queen. At least the observers were common subjects, not the courtiers whose biting wit would find her disheveled state an easy target. They bowed themselves out of her way, and stepped carefully over her muddy trail once she passed.

Her intention was to go first to the Queen's chambers, in hopes of finding her there, but something stopped her along the way: the sight of a pair of elf-knights standing watch on either side of two tall, copper-paneled doors. Members of the Onyx Guard, both of them, and as such they owed salutes to only two people in the whole of the court.

They saluted the young man at her side. "Lord Galen."

Lord— Too late, Irrith realized the bows on the way here had not been for her. Of course they hadn't—how long since she'd been in the Onyx Hall? And who would recognize her beneath the drying shell of mud? Turning to the gentleman, she said accusingly, "You're the Prince of the Stone!"

He blushed charmingly and muttered something half-intelligible about having forgotten his manners. More likely, Irrith thought, he was too self-conscious to bring it up. New, no doubt. Yes, she remembered hearin

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...