1

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

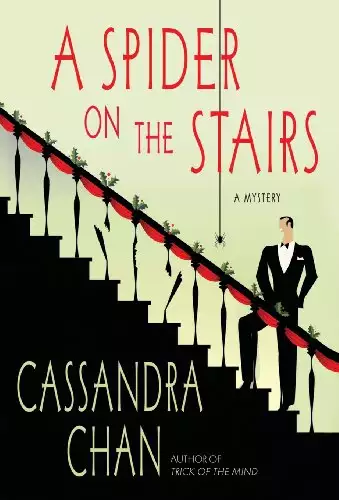

A Spider on the Stairs

Cassandra Chan

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved

Close