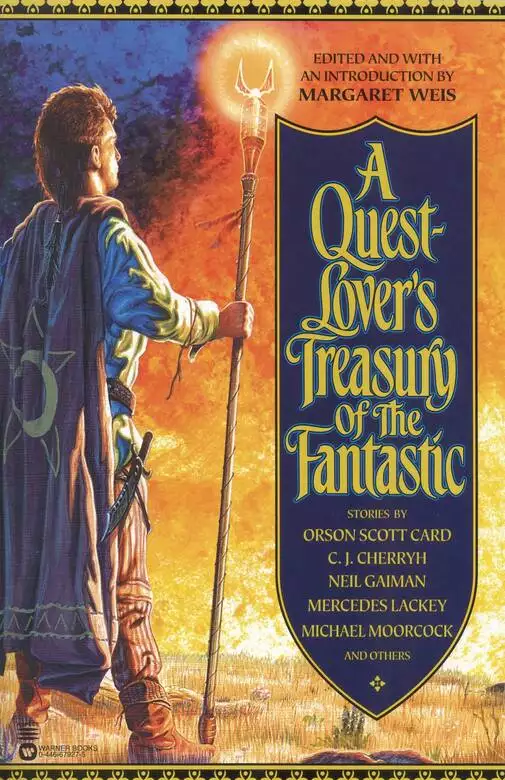

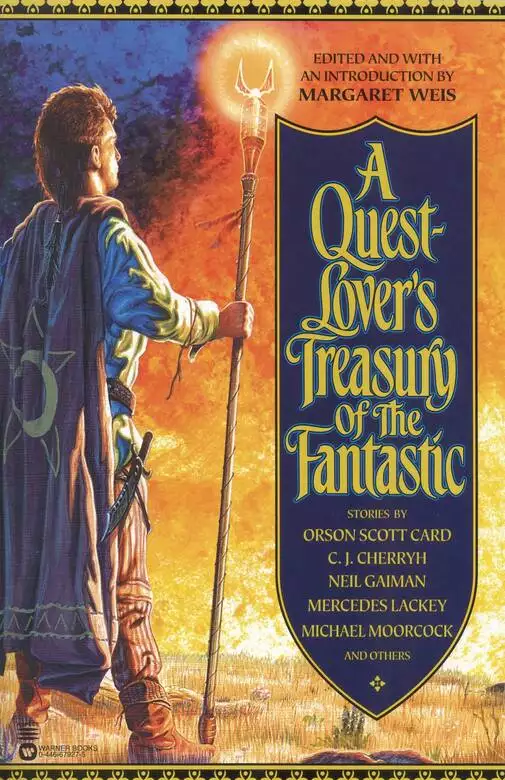

A Quest-Lover's Treasury of the Fantastic

- eBook

- Paperback

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Going all the way back to Homer's Odyssey, the 'quest' is a popular and well-respected story-telling format in Western literature. This volume collects classic quest stories, including tales from by Neil Gaiman and Marion Zimmer Bradley, and the Mercedes Lackey story 'The Cup and The Cauldron'.

Release date: September 9, 2009

Publisher: Aspect

Print pages: 322

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

A Quest-Lover's Treasury of the Fantastic

Margaret Weis

Copyright © 2002 by Margaret Weis and Tekno Books

All rights reserved.

“Introduction” by Margaret Weis. Copyright © 2002 by Margaret Weis.

“Gwydion and the Dragon” by C.J. Cherryh. Copyright © 1991 by C.J. Cherryh. First published in Once Upon a Time. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Misericorde” by Karl Edward Wagner. Copyright © 1983 by Karl Edward Wagner. First published in The Sorcerer's Apprentice #17. Reprinted by permission of The Karl Edward Wagner Literary Group.

“The Barbarian” by Poul Anderson. Copyright © 1956 by Fantasy House, Inc. First published in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, May 1956. Reprinted by permission of the author and his agents, Chichak, Inc.

“The Silk and the Song” by Charles L. Fontenay. Copyright © 1956 by Fantasy House, Inc. First published in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, July 1956. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Mirror, Mirror on the Lam” by Tanya Huff. Copyright © 1997 by Tanya Huff. First published in Wizard Fantastic. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Chivalry” by Neil Gaiman. Copyright © 1992 by Neil Gaiman. First published in Grails: Quests, Visitations, and Other Occurrences. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Firebearer” by Lois Tilton. Copyright © 1990 by Lois Tilton. First published in Dragon magazine, January 1990. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“The Bully and the Beast” by Orson Scott Card. Copyright © 1979 by Orson Scott Card. First published in Other Worlds #1. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“A Time for Heroes” by Richard Parks. Copyright © 1996 by Richard Parks. First published in The Shimmering Door. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“The Cup and the Cauldron” by Mercedes Lackey. Copyright © 1992 by Mercedes Lackey. First published in Grails: Quests, Visitations, and Other Occurrences. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“The Lands Beyond the World” by Michael Moorcock. Copyright © 1977 by Michael Moorcock and Linda Moorcock. First published

in Flashing Swords #4. Reprinted by permission of the author and his agents, the Howard Morhaim Literary Agency.

Aspect® name and logo are registered trademarks of Warner Books, Inc.

Warner Books, Inc.,

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue

New York, NY 10017

Visit our website at

www.HachetteBookGroup.com

First eBook Edition: September 2009

ISBN: 978-0-446-56477-9

Margaret Weis

I once heard author Gary Paulsen tell a group of children that the very first authors were those who flung the wolfskins over

their heads and crouched in the firelight to tell their tales to the tribe. I am certain that among the tales these early

storytellers told their people were those of men and women who set off on quests.

The quest story has been handed down through time because it is story to which each one of us can relate. The quest story

mirrors the journey of our lives. From the moment of our birth, we begin the great quest that ends in this world with our

death and, perhaps, at that point starts anew.

One might say that almost every story ever written or told is a quest story in one form or another. Sherlock Holmes quested

for truth and justice. Elizabeth Bennet set out upon a famous quest for love. D'Artagnan took the road to Paris in search

of adventure and honor. Mr. Pickwick left London to discover humanity (and good food!).

Quests are not relegated to days past. We read tales of ancient heroes who set about searching for the golden fleece and tales

of modern heroes who take up the quest for golden medals at once-ancient games.

Most important, the quest story involves a search for self.

Charles Dickens wrote in David Copperfield: “Whether I shall turn out to be the hero of my own life, or whether that station will be held by anybody else, these pages

must show.”

We turn to quest stories to learn how to be the heroes of our own lives. Quest stories show us how other people live their

lives, face their challenges, and deal with their problems. We may emulate them or shun them, pity them or admire them, hate

them or weep for them, but we always learn something from them.

In each story we read, whether it is the quest for the Holy Grail or the search for the Hound of the Baskervilles, we are

studying mankind. We are studying ourselves and examining our own quests. In this book, you will find some of your favorite

fantasy authors writing stories of men and women questing, striving, seeking, finding.

Each day begins a new quest for each of us. Take along this book of some of my favorite quest stories on yours.

C.J. Cherryh

Once upon a time there was a dragon, and once upon that time a prince who undertook to win the hand of the elder and fairer

of two princesses.

Not that this prince wanted either of Madog's daughters, although rumors said that Eri was as wise and as gentle, as sweet

and as fair as her sister, Glasog, was cruel and ill-favored. The truth was that this prince would marry either princess if

it would save his father and his people; and neither if he had had any choice in the matter. He was Gwydion ap Ogan, and of

princes in Dyfed he was the last.

Being a prince of Dyfed did not, understand, mean banners and trumpets and gilt armor and crowds of courtiers. King Ogan's

palace was a rambling stone house of dusty rafters hung with cooking pots and old harnesses; King Ogan's wealth was mostly

in pigs and pastures—the same as all Ogan's subjects; Gwydion's war-horse was a black gelding with a crooked blaze and shaggy

feet, who had fought against the bandits from the high hills. Gwydion's armor, serviceable in that perpetual warfare, was

scarred leather and plain mail, with new links bright among the old; and lance or pennon he had none—the folk of Ogan's kingdom

were not lowland knights, heavily armored, but hunters in the hills and woods, and for weapons this prince carried only a

one-handed sword and a bow and a quiver of gray-feathered arrows.

His companion, riding beside him on a bay pony, happened through no choice of Gwydion's to be Owain ap Llodri, the hound-master's

son, his good friend, by no means his squire: Owain had lain in wait along the way, on a borrowed bay mare—Owain had simply

assumed he was going, and that Gwydion had only hesitated, for friendship's sake, to ask him. So he saved Gwydion the necessity.

And the lop-eared old dog trotting by the horses' feet was Mili: Mili was fierce with bandits, and had respected neither Gwydion's

entreaties nor Owain's commands thus far: stones might drive her off for a few minutes, but Mili came back again, that was

the sort Mili was. That was the sort Owain was too, and Gwydion could refuse neither of them. So Mili panted along at the

pace they kept, with big-footed Blaze and the bow-nosed bay, whose name might have been Swallow or maybe not—the poets forget—and

as they rode Owain and Gwydion talked mostly about dogs and hunting.

That, as the same poets say, was the going of Prince Gwydion into King Madog's realm.

Now no one in Dyfed knew where Madog had come from. Some said he had been a king across the water. Some said he was born of

a Roman and a Pict and had gotten sorcery through his mother's blood. Some said he had bargained with a dragon for his sorcery—certainly

there was a dragon: devastation followed Madog's conquests, from one end of Dyfed to the other.

Reasonably reliable sources said Madog had applied first to King Bran, across the mountains, to settle at his court, and Bran

having once laid eyes on Madog's elder daughter, had lusted after her beyond all good sense and begged Madog for her.

Give me your daughter, Bran had said to Madog, and I'll give you your heart's desire. But Madog had confessed that Eri was

betrothed already, to a terrible dragon, who sometimes had the form of a man, and who had bespelled Madog and all his house:

if Bran could overcome this dragon he might have Eri with his blessings, and his gratitude and the faithful help of his sorcery

all his life; but if he died childless, Madog, by Bran's own oath, must be his heir.

That was the beginning of Madog's kingdom. So smitten was Bran that he swore to those terms, and died that very day, after

which Madog ruled in his place.

After that Madog had made the same proposal to three of his neighbor kings, one after the other, proposing that each should

ally with him and unite their kingdoms if the youngest son could win Eri from the dragon's spell and provide him an heir.

But no prince ever came back from his quest. And the next youngest then went, until all the sons of the kings were gone, so

that the kingdoms fell under Madog's rule.

After them, Madog sent to King Ban, and his sons died, last of all Prince Rhys, Gwydion's friend. Ban's heart broke, and Ban

took to his bed and died.

Some whispered now that the dragon actually served Madog, that it had indeed brought Madog to power, under terms no one wanted

to guess, and that this dragon did indeed have another form, which was the shape of a knight in strange armor, who would become

Eri's husband if no other could win her. Some said (but none could prove the truth of it) that the dragon-knight had come

from far over the sea, and that he devoured the sons and daughters of conquered kings, that being the tribute Madog gave him.

But whatever the truth of that rumor, the dragon hunted far and wide in the lands Madog ruled and did not disdain to take

the sons and daughters of farmers and shepherds too. Devastation went under his shadow, trees withered under his breath, and

no one saw him outside his dragon shape and returned to tell of it, except only Madog and (rumor said) his younger daughter,

Glasog, who was a sorceress as cruel as her father.

Some said that Glasog could take the shape of a raven and fly over the land choosing whom the dragon might take. The people

called her Madog's Crow, and feared the look of her eye. Some said she was the true daughter of Madog and that Madog had stolen

Eri from Faerie, and given her mother to the dragon; but others said they were twins, and that Eri had gotten all that an

ordinary person had of goodness, while her sister, Glasog—

“Prince Gwydion,” Glasog said to her father, “would have come on the quest last year with his friend Rhys, except his father's

refusing him, and Prince Gwydion will not let his land go to war if he can find another course. He'll persuade his father.”

“Good,” Madog said. “That's very good.” Madog smiled, but Glasog did not. Glasog was thinking of the dragon. Glasog harbored

no illusions: the dragon had promised Madog that he would be king of all Wales if he could achieve this in seven years; and

rule for seventy and seven more with the dragon's help.

But if he failed—failed by the seventh year to gain any one of the kingdoms of Dyfed, if one stubborn king withstood him and

for one day beyond the seven allotted years, kept him from obtaining the least, last stronghold of the west, then all the

bargain was void and Madog would have failed in everything.

And the dragon would claim a forfeit of his choosing.

That was what Glasog thought of, in her worst nightmares: that the dragon had always meant to have all the kingdoms of the

west with very little effort—let her father win all but one and fail, on the smallest letter of the agreement. What was more,

all the generals in all the armies they had taken agreed that the kingdom of Ogan could never be taken by force: there were

mountains in which resistance could hide and not even dragonfire could burn all of them; but most of all there was the fabled

Luck of Ogan, which said that no force of arms could defeat the sons of Ogan.

Watch, Madog had said. And certainly her father was astute, and cunning, and knew how to snare a man by his pride. There's

always a way, her father had said, to break a spell. This one has a weakness. The strongest spells most surely have their

soft spots.

And Ogan had one son, and that was Prince Gwydion.

Now we will fetch him, Madog said to his daughter. Now we will see what his luck is worth.

The generals said, “If you would have a chance in war, first be rid of Gwydion.”

But Madog said, and Glasog agreed, there are other uses for Gwydion.

“It doesn't look different,” Owain said as they passed the border stone.

It was true. Nothing looked changed at all. There was no particular odor of evil, or of threat. It might have been last summer,

when the two of them had hunted with Rhys. They had used to hunt together every summer, and last autumn they had tracked the

bandit Llewellyn to his lair, and caught him with stolen sheep. But in the spring Ban's sons had gone to seek the hand of

Madog's daughter, and one by one had died, last of them, in early summer, Rhys himself.

Gwydion would have gone, long since, and long before Rhys. A score of times Gwydion had approached his father, King Ogan,

and his mother, Queen Belys, and begged to try his luck against Madog, from the first time Madog's messenger had appeared

and challenged the kings of Dyfed to war or wedlock. But each time Ogan had refused him, arguing in the first place that other

princes, accustomed to warfare on their borders, were better suited, and better armed, and that there were many princes in

Dyfed, but he had only one son.

But when Rhys had gone and failed, the last kingdom save that of King Ogan passed into Madog's hands. And Gwydion, grief-stricken

with the loss of his friend, said to his parents, “If we had stood together we might have defeated this Madog; if we had taken

the field then, together, we might have had a chance; if you had let me go with Rhys one of us might have won and saved the

other. But now Rhys is dead and we have Madog for a neighbor. Let me go when he sends to us. Let me try my luck at courting

his daughter. A war with him now we may not lose, but we cannot hope to win.”

Even so Ogan had resisted him, saying that they still had their mountains for a shield, difficult going for any army; and

arguing that their luck had saved them this far and that it was rash to take matters into their own hands.

Now the nature of that luck was this: that of the kingdoms in Dyfed, Ogan's must always be poorest and plainest. But that

luck meant that they could not fail in war nor fail in harvest: it had come down to them from Ogan's own great-grandfather

Ogan ap Ogan of Llanfynnyd, who had sheltered one of the Faerie unaware; and only faithlessness could break it—so great-grandfather

Ogan had said. So: “Our luck will be our defense,” Ogan argued with his son. “Wait and let Madog come to us. We'll fight him

in the mountains.”

“Will we fight a dragon? Even if we defeat Madog himself, what of our herds, what of our farmers and our freeholders? Can

we let the land go to waste and let our people feed this dragon, while we hide in the hills and wait for luck to save us?

Is that faithfulness?” That was what Gwydion had asked his father, while Madog's herald was in the hall—a raven black as unrepented

sin … or the intentions of a wizard.

“Madog bids you know,” this raven had said, perched on a rafter of Ogan's hall, beside a moldering basket and a string of

garlic, “that he has taken every kingdom of Dyfed but this. He offers you what he offered others: if King Ogan has a son worthy

to win Madog's daughter and get an heir, then King Ogan may rule in peace over his kingdom so long as he lives, and that prince

will have titles and the third of Madog's realm besides….

“But if the prince will not or cannot win the princess, then Ogan must swear Madog is his lawful true heir. And if Ogan refuses

this, then Ogan must face Madog's army, which now is the army of four kingdoms each greater than his own. Surely,” the raven

had added, fixing all present with a wicked, midnight eye, “it is no great endeavor Madog asks—simply to court his daughter.

And will so many die, and so much burn? Or will Prince Gwydion win a realm wider than your own? A third of Madog's lands is

no small dowry and inheritance of Madog's kingdom is no small prize.”

So the raven had said. And Gwydion had said to his mother, “Give me your blessing,” and to his father, Ogan: “Swear the oath

Madog asks. If our luck can save us it will save me and win me this bride; but if it fails me in this it would have failed

us in any case.”

Maybe, Gwydion thought as they passed the border, Owain was a necessary part of that luck. Maybe even Mili was. It seemed

to him now that he dared reject nothing that loved him and favored him, even if it was foolish and even if it broke his heart:

his luck seemed so perilous and stretched so thin already he dared not bargain with his fate.

“No sign of a dragon, either,” Owain said, looking about them at the rolling hills.

Gwydion looked about him too, and at the sky, which showed only the lazy flight of a single bird.

Might it be a raven? It was too far to tell.

“I'd think,” said Owain, “it would seem grimmer than it does.”

Gwydion shivered as if a cold wind had blown. But Blaze plodded his heavy-footed way with no semblance of concern, and Mili

trotted ahead, tongue lolling, occasionally sniffing along some trail that crossed theirs.

“Mili would smell a dragon,” Owain said.

“Are you sure?” Gwydion asked. He was not. If Madog's younger daughter could be a raven at her whim he was not sure what a

dragon might be at its pleasure.

That night they had a supper of brown bread and sausages that Gwydion's mother had sent, and ale that Owain had with him.

“My mother's brewing,” Owain said. “My father's store.” And Owain sighed and said: “By now they must surely guess I'm not

off hunting.”

“You didn't tell them?” Gwydion asked. “You got no blessing in this?”

Owain shrugged, and fed a bit of sausage to Mili, who gulped it down and sat looking at them worshipfully.

Owain's omission of duty worried Gwydion. He imagined how Owain's parents would first wonder where he had gone, then guess,

and fear for Owain's life, for which he held himself entirely accountable. In the morning he said, “Owain, go back. This is

far enough.”

But Owain shrugged and said, “Not I. Not without you.” Owain rubbed Mili's ears. “No more than Mili, without me.”

Gwydion had no least idea now what was faithfulness and what was a young man's foolish pride. Everything seemed tangled. But

Owain seemed not in the least distressed.

Owain said, “We'll be there by noon tomorrow.”

Gwydion wondered, Where is this dragon? and distrusted the rocks around them and the sky over their heads. He felt a presence

in the earth—or thought he felt it. But Blaze and Swallow grazed at their leisure. Only Mili looked worried—Mili pricked up

her ears, such as those long ears could prick, wondering, perhaps, if they were going to get to bandits soon, and whether

they were, after all, going to eat that last bit of breakfast sausage.

“He's on his way,” Glasog said. “He's passed the border.”

“Good,” said Madog. And to his generals: “Didn't I tell you?”

The generals still looked worried.

But Glasog went and stood on the walk of the castle that had been Ban's, looking out over the countryside and wondering what

the dragon was thinking tonight, whether the dragon had foreseen this as he had foreseen the rest, or whether he was even

yet keeping some secret from them, scheming all along for their downfall.

She launched herself quite suddenly from the crest of the wall, swooped out over the yard and beyond, over the seared fields.

The dragon, one could imagine, knew about Ogan's luck. The dragon was too canny to face it—and doubtless was chuckling in

his den in the hills.

Glasog flew that way, but saw nothing from that cave but a little curl of smoke—there was almost always smoke. And Glasog

leaned toward the west, following the ribbon of a road, curious, and wagering that the dragon this time would not bestir himself.

Her father wagered the same. And she knew very well what he wagered, indeed she did: duplicity for duplicity—if not the old

serpent's aid, then human guile; if treachery from the dragon, then put at risk the dragon's prize.

Gwydion and Owain came to a burned farmstead along the road. Mili sniffed about the blackened timbers and bristled at the

shoulders, and came running back to Owain's whistle, not without mistrustful looks behind her.

There was nothing but a black ruin beside a charred, brittle orchard.

“I wonder,” Owain said, “what became of the old man and his wife.”

“I don't,” said Gwydion, worrying for his own parents, and seeing in this example how they would fare in any retreat into

the hills.

The burned farm was the first sign they had seen of the dragon, but it was not the last. There were many other ruins, and

sad and terrible sights. One was a skull sitting on a fence row. And on it sat a raven.

“This was a brave man,” it said, and pecked the skull, which rang hollowly, and inclined its head toward the field beyond.

“That was his wife. And farther still his young daughter.”

“Don't speak to it,” Gwydion said to Owain. They rode past, at Blaze's plodding pace, and did not look back.

But the raven flitted ahead of them and waited for them on the stone fence. “If you die,” the raven said, “then your father

will no longer believe in his luck. Then it will leave him. It happened to all the others.”

“There's always a first,” said Gwydion.

Owain said, reaching for his bow: “Shall I shoot it?”

But Gwydion said: “Kill the messenger for the message? No. It's a foolish creature. Let it be.”

It left them then. Gwydion saw it sometimes in the sky ahead of them. He said nothing to Owain, who had lost his cheerfulness,

and Mili stayed close by them, sore of foot and suspicious of every breeze.

There were more skulls. They saw gibbets and stakes in the middle of a burned orchard. There was scorched grass, recent and

powdery under the horses' hooves. Blaze, who loved to snatch a bite now and again as he went, moved uneasily, snorting with

dislike of the smell, and Swallow started at shadows.

Then the turning of the road showed them a familiar brook, and around another hill and beyond, the walled holding that had

been King Ban's, in what had once been a green valley. Now it was burned, black bare hillsides and the ruin of hedges and

orchards.

So the trial they had come to find must be here, Gwydion thought, and uneasily took up his bow and picked several of his best

arrows, which he held against his knee as he rode. Owain did the same.

But they reached the gate of the low-walled keep unchallenged, until they came on the raven sitting, whetting its beak on

the stone. It looked at them solemnly, saying, “Welcome, Prince Gwydion. You've won your bride. Now how will you fare, I wonder.”

Men were coming from the keep, running toward them, others, under arms, in slower advance.

“What now?” Owain asked, with his bow across his knee; and Gwydion lifted his bow and bent it, aiming at the foremost.

The crowd stopped, but a black-haired man in gray robes and a king's gold chain came alone, holding up his arms in a gesture

of welcome and of peace. Madog himself? Gwydion wondered, while Gwydion's arm shook and the string trembled in his grip. “Is

it Gwydion ap Ogan?” that man asked—surely no one else but Madog would wear that much gold. “My son-in-law to be! Welcome!”

Gwydion, with great misgivings, slacked the string and let down the bow, while fat Blaze, better trained than seemed, finally

shifted feet. Owain lowered his bow too, as King Madog's men opened up the gate. Some of the crowd cheered as they rode in,

and more took it up, as if they had only then gained the courage or understood it was expected. Blaze and Swallow snorted

and threw their heads at the racket, as Gwydion and Owain put away their arrows, unstrung their bows and hung them on their

saddles.

But Mili stayed close by Owain's legs as they dismounted, growling low in her throat, and barked one sharp warning when Madog

came close. “Hush,” Owain bade her, and knelt down more than for respect, keeping one hand on Mili's muzzle and the other

in her collar, whispering to her, “Hush, hush, there's a good dog.”

Gwydion made the bow a prince owed to a king and prospective father-in-law, all the while thinking that there had to be a

trap in this place. He was entirely sorry to see grooms lead Blaze and Swallow away, and kept Owain and Mili constantly in

the tail of his eye as Madog took him by the arms and hugged him. Then Madog said, catching all his attention, eye to eye

with him for a moment, “What a well-favored young man you are. The last is always best. —So you've killed the dragon.”

Gwydion thought, Somehow we've ridden right past the trial we should have met. If I say no, he will find cause to disallow

me; and he'll kill me and Owain and all our kin.

But lies were not the kind of dealing his father had taught him; faithfulness was the rule of the house of Ogan; so Gwydion

looked the king squarely in the eyes and said, “I met no dragon.”

Madog's eyes showed surprise, and Madog said: “Met no dragon?”

“Not a shadow of a dragon.”

Madog grinned and clapped him on the shoulder and showed him to the crowd, saying, “This is your true prince!”

Then the crowd cheered in earnest, and even Owain and Mili looked heartened. Owain rose with Mili's collar firmly in hand.

Madog said then to Gwydion, under his breath, “If you had lied you would have met the dragon here and now. Do you know you're

the first one who's gotten this far?”

“I saw nothing,” Gwydion said again, as if Madog had not understood him. “Only burned farms. Only skulls and bones.”

Madog turned a wide smile toward him, showing teeth. “Then it was your destiny to win. Was it not?” And Madog faced him about

toward the doors of the keep. “Daughter, daughter, come out!”

Gwydion hesitated a step, expecting he knew not what—the dragon itself, perhaps: his wits went scattering toward the gate,

the horses being led away, Mili barking in alarm—and a slender figure standing in the doorway, all white and gold. “My elder

daughter,” Madog said. “Eri.”

Gwydion went as he was led, telling himself it must be true, after so much dread of this journey and so many friends' lives

lost—obstacles must have fallen down for him, Ogan's luck must still be working….

The young bride waiting for him was so beautiful, so young and so—kind—was the first word that came to him—Eri smiled and

immediately it seemed to him she was innocent of all the grief around her, innocent and good as her sister was reputed cruel

and foul.

He took her hand, and the folk of the keep all cheered, calling him their prince; and if any were Ban's people, those wishes

might well come from the heart, with fervent hopes of rescue. Pipers began to play, gentle hands urged them both inside, and

in this desolate land some woman found flowers to give Eri.

“Owain?” Gwydion cried, looking back, suddenly seeing no sign of him or of Mili: “Owain!”

He refused to go farther until Owain could part the crowd and reach his side, Mili firmly in hand. Owain looked breathless

and frightened. Gwydion felt the same. But the crowd pushed and pulled at them, the pipers piped and dancers danced, and they

brought them into a hall smelling of food and ale.

It can't be this simple, Gwydion still thought, and made up his mind that no one should part him from Owain, Mili, or their

swords. He looked about him, bedazzled, at a wedding feast that must have taken days to prepare.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...