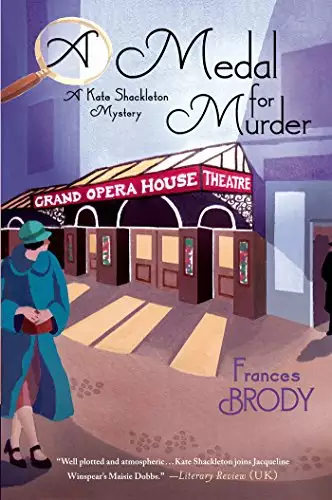

Medal for Murder, A

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

A Medal for Murder

Frances Brody

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved

Close