- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

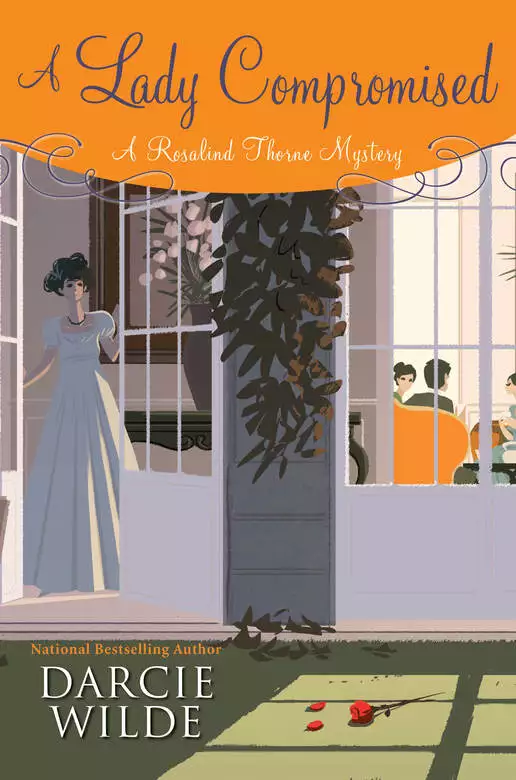

Fans of Jane Austen have fallen in love with Darcie Wilde's mystery series featuring Rosalind Thorne, a young woman adept at helping ladies of the ton navigate the darker corners of Regency England--while revealing Society's most shocking secrets...

Rosalind is pleased when she's invited to Cassel House to help her friend, Louisa, prepare for her upcoming wedding. But that's not the only event on her agenda. The trip will also afford Rosalind the chance to see Devon Winterbourne, the newly minted Duke of Casselmaine. Devon and Rosalind were on the verge of betrothal before the infamous Thorne family scandal derailed their courtship. Now Rosalind wonders if there's a chance their love might reignite.

Devon is as handsome as Rosalind remembers and it's clear the attraction they once shared hasn't waned. But their time together is interrupted by one crisis after another--not the least of which is an awkwardly timed request for help from Louisa's friend, Helen Corbyn.

Not long ago, the untimely death of Helen's brother, William, was ruled a suicide, but few people truly believe he took his own life. Helen needs to know what really happened--especially since she's engaged to the man some suspect of secretly killing William.

While Rosalind desperately wants to help, she fears her efforts might cast a pall over Louisa's nuptials, not to mention her reunion with Devon. But when another untimely death rocks the ton, Rosalind has no choice but to uncover the truth before more people die...even if her actions threaten her future with Devon.

Release date: November 24, 2020

Publisher: Kensington Books

Print pages: 304

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

A Lady Compromised

Darcie Wilde

“I will be visiting a grand manor house on an estate of thousands of acres,” Rosalind corrected Alice mildly as she set the silver tray down. The elegant service dwarfed her small tea table. Very little of the Thorne family plate had survived their abrupt shifts of fortune. Thanks to several domestic miracles, however, the tea service remained intact. “And it isn’t as if I’ll be just sitting in the parlor. I will be helping get Louisa to the altar in as much style as the local church can offer. It shall be a positive whirlwind of activity that’s hardly going to leave me ‘shut up’ with anybody.” Rosalind paused. “Besides, Lord Casselmaine cannot be called my former fiancé. We were never formally engaged.”

“Formally, you weren’t, but practically you were. You cannot deny that.”

“I could, but would it get me anywhere?”

“Probably not.” Alice helped herself to a somewhat lopsided bread-and-butter sandwich.

Rosalind had fixed their tea herself. Her housekeeper, Mrs. Kendricks, was fully occupied with the work of closing up their small London house for the three weeks of Rosalind’s stay in the country. In this room, all but one of the lamps had been emptied of oil and wicks, and all the most valuable movables were already locked away in the back cupboard. As soon as Alice left, Rosalind would spend the remainder of the day with her correspondence. She had to be sure all her accounts were as settled as they could be, and then answer a last few notes from friends and acquaintances. There was the pair of unusually important letters that she must forward to Mr. Sanderson Faulks. These would need to be delivered by hand. Mr. Faulks was an old friend of Rosalind’s, and her family’s, and he had recently begun holding some particularly sensitive correspondence in a sort of trust for her.

“Then there’s the fact that your former fiancé is now a duke,” Alice went on. “And is possibly planning on offering for you . . .”

“All right, Alice!” cried Rosalind. “Yes, I am nervous. Does that satisfy you?”

Alice put down her cup. “No, I’m worried about you.”

Rosalind felt her brows arch. “Why should you be?”

Alice took her time in answering, which was surprising. Normally, Alice Littlefield spoke and moved and thought with a speed that was difficult to keep pace with. Rosalind, on the other hand, had always been far more deliberate, with a habit of looking steadily at whoever was speaking that some found disconcertingly direct.

The friends contrasted in their looks as much as in their temperaments. Alice was petite and dark haired, with a warm complexion and lively brown eyes. Rosalind Thorne, on the other hand, was tall and golden haired, with a figure more suited to sweeping skirts and cinched bodices of the grand dames of the previous era than the high-waisted Josephine gowns and pelisses that were currently in fashion.

“Rosalind, I know you better than anyone, even my brother,” said Alice finally. “You won’t deny that Lord Casselmaine represents a dreadful temptation. He’s rich, landed, and titled, and it’s not just any title, but an old one that puts him in the very first circles. If you married him, you would be returned to society in grandest possible style. It’s a dazzling prospect, and it could easily keep you from appreciating the alternatives.”

“And what is it you see as my alternatives?”

“Remaining as you are. Acknowledging for once and for all that the haut ton is no longer where you live, it’s just someplace you visit. And keeping on with your business. I know”—Alice held up her hand before Rosalind could interject—“it is contrary to all accepted etiquette that I should accuse a gently bred woman of engaging in business. But women come to you with their problems, and when you help them, you are materially compensated for your time and effort. That’s a business, and you are very good at it. It’s new and it’s different and you like it and it makes you happy, and you won’t be able to do any of it if you’re swaddled up as the Duchess of Casselmaine.

“There.” Alice folded her hands. “I’ve said my piece. You may now reprove me at your leisure.”

But all Rosalind did was smile and take up a sandwich for herself.

“Alice, everything you just said—those are all the reasons I have to go. If I hold back, I will always wonder if I was afraid, and what might have been. And,” she added with a bracing breath, “I shall not just be idling about on picnics or helping Louisa write her thank-you notes. I’ve had a letter.”

Rosalind went to her desk, pulled the letter from off her stack, and unfolded it for her friend. While she returned to her tea and sandwich, Alice read:

“Well.” Alice refolded the letter. “I’m afraid she undoes her claim of not being a hysteric by her connection to Louisa. That girl’s always had more than a touch of the dramatic about her. Why, she went into full mourning when that actor died. What was his name . . . ?”

“Yes,” agreed Rosalind. “But at bottom, Louisa’s a sensible young woman. I do not think I can turn down a friend of hers without a hearing . . . Now what is that for?”

Alice was frowning at her.

“I’d say it’s nothing at all,” replied Alice. “But I know you’d be cross with me. So, I will say I am making a quiet wager with myself.”

“On what point?”

“You’ll find out once you have completed your restful stay in the idyllic English countryside,” Alice told her. “You know, I wish I could go with you, but we lady novelists must stick to our work. And, of course, you’re not the only one with a wedding to plan.”

“Have George and Hannah set a date?” George Littlefield was Alice’s older brother.

“It’s to be in October. Hannah wants time to make her dress, and there are other arrangements . . .” She let the sentence trail off.

Alice currently kept house with George, and while both her brother and his fiancée had insisted Alice was welcome to stay, she had no intention of wearing out that particular welcome. She wanted new rooms for herself, but with her limited means, respectable places were proving difficult to find.

“It will all come together in time, I’m sure,” said Rosalind. “Now, tell me how A.E. Littlefield’s novel is progressing.”

The friends finished their tea, all the while chatting about Alice’s work, mutual acquaintances, and the end of the season flourishes Alice had attended as a society writer.

At last, Alice gathered up her things and Rosalind showed her to the door.

“You will write to me, won’t you?” said Alice.

“Of course I will. Daily if you like.”

“Probably we needn’t go that far but . . . I don’t know, Rosalind, I still worry.”

Rosalind smiled and pressed Alice’s hand. “I’d tell you to stop, but I know that never works. Therefore, I will promise to take good care of myself and not to let the Dowager Lady Casselmaine intimidate me in any way.”

Instead of answering, Alice gave Rosalind a quick peck on the cheek and took herself out the door.

The parlor seemed quieter than ever without Alice to help fill it. Rosalind found herself returning to the sofa and swirling at the dregs of her tea distractedly.

When she was a girl, an invitation to stay was a cause for excitement. It meant seeing old friends, buying new clothes, and of course, the possibility of flirting with young men. But it had been a long time since she had been invited anywhere simply as a guest.

Her family’s assorted failures meant Rosalind had spent the past seven anxious years making her own way in the world. Now when she received invitations, they were all to house parties she had helped a hostess organize. During her stays, she had chores to complete and tasks to be accounted for, not to mention an endless array of plans to set in motion on behalf of her hostess.

But this time was different. This time, Rosalind Thorne, daughter of Sir Reginald Thorne, baronet (and forger, drunkard, liar, and suspected panderer), was invited to spend a month at Cassell House by Devon Winterbourne, Duke of Casselmaine. Ostensibly, it was to help his young cousin Louisa prepare for her wedding. In reality, it was to give him and Rosalind a chance to recommence a courtship cut off by her father’s downfall and his brother’s death.

And now, it seemed, she would also be helping a young woman she’d never met out of her difficulties.

Alice had been right from the beginning. Rosalind was very nervous.

Rosalind was not entirely unacquainted with the country. House parties had been part of her girlhood, at least during those times when her father had been in funds and in friends. Despite this, each time she ventured outside of London, she still felt like she was entering into a foreign country.

She had, however, read enough novels to know that an author typically described the first sight of the hero’s ancestral seat with a sweeping groundswell of prose. As the carriage pulled past the tree line of the Cassell House park, however, Rosalind found herself limited to just three syllables.

“Oh. My. Word.”

“Yes,” murmured her companion, Mrs. Showell. “I quite agree.”

Cassell House was a manor on the grand scale. From what Rosalind could see, the house formed a U around a gravel yard, complete with (open) wrought iron gates. Dozens of windows sparkled in the midday sun, each one ornamented with all manner of coronets, crenellations, yet more crests. There were even cupolas sprouting from the rooftops, one for each wing, and a grand central dome that was probably truly impressive when seen from inside.

The overall effect was of a woman in a ballgown made for someone else. Nothing seemed to quite fit.

“It was the late duke’s design, I’m afraid, and Hugh’s.” Mrs. Showell sighed. “The original house dated from Queen Elizabeth’s day. It was not grand in the modern style, but it was graceful. I’m afraid I find this new edifice a trifle . . . inconvenient at times.”

Mrs. Showell was Louisa Winterbourne’s aunt and the sister of the Dowager Lady Casselmaine. A brisk, practical, experienced woman, Mrs. Showell had shepherded her vivacious niece through two London Seasons, to the successful conclusion that was Louisa’s betrothal to one Mr. Firth Rollins. She had also kindly agreed to accompany Rosalind on the journey out to the country.

The driver steered them into the yard and turned the carriage expertly so the door aligned with the hall’s grand entrance. A liveried footman was there to place the step, open the door, and help Rosalind and Mrs. Showell out.

Rosalind’s foot had barely touched the gravel before Louisa herself came running down the hall’s front steps.

“Rosalind! Finally!”

“Louisa!” cried Aunt Showell in affectionate exasperation. “You’ll be a married woman in two weeks!”

“And I swear at that exact moment, all running out of doors will cease.” Louisa ducked around the edge of her aunt’s bonnet to give her a quick, affectionate kiss. “Thank you so much, dear Aunt Showell, for going to fetch her!”

Mrs. Showell waved off her enthusiastic niece and Rosalind laughed. “Well, there’s no need to ask how you are, Louisa. I can see for myself. You look wonderful.”

Louisa Winterbourne might not be heir to title or fortune, but she had inherited the Winterbourne looks, complete with shining black hair and bright gray eyes. If her ruddy complexion was short of the roses-and-cream ideal of English girlhood, it had the advantage of turning a pleasing golden color in summer. She possessed all the usual young lady’s frivolities, plus a few extras, but Louisa was intelligent, kind-hearted, and trustworthy, and Rosalind was glad to call her a friend.

Just now, though, Louisa rolled her eyes. “Wonderful?” she cried. “I look distracted, is what I look. I’m absolutely buried under a drift of letters, and cards, and what-have-you, and there are more arriving hourly. I don’t know where they’re all coming from! I’ve never met half these women!”

“It’s no surprise, Louisa,” Rosalind said. “You’re getting married from Cassell House. The consequence was bound to rub off.”

“Well, that consequence won’t do any good if I’m smothered to death under an avalanche of paper.” Louisa grabbed both of Rosalind’s hands. “Swear you’re here to help with the replies.”

“I’m here to help with whatever you need. We’ll get you to church on time and unsmothered, I promise.”

“Oh, I’m not worried, exactly. It’s more—” But Louisa caught Aunt Showell’s deepening frown and cut herself off. “But I’m keeping you standing out in the yard when you’re probably exhausted. Come inside.” She hooked her arm through Rosalind’s and drew her up the steps.

The interior of Cassell House was even more astonishing than Rosalind could have imagined. The light-filled foyer soared upward for a full three stories. The walls and sweeping curved stair were all made of white marble veined with gray and pink. The great Doric columns were polished pink granite. The carpets and hangings reproduced the colors of the Casselmaine livery: pale blue, silver, and nut brown. The tables and chairs were all gilded and marbled, carved and curved in the French imperial style.

It is like walking into an ice cavern.

Porters and pages in blue and silver livery closed the doors behind the women. Young maids in gray and white came forward to help remove traveling cloaks and bonnets, which were handed to yet another group of footmen to be borne back to the appropriate rooms.

“Here is Emerson.” Louisa beckoned to a round-faced woman in the severe black dress of an upper servant who stood out like a shadow in all this white and pink. “She’s to be your maid and help Mrs. Kendricks when she gets here.”

“Miss.” Emerson curtsied.

“I’ll let you get settled, and then you and I can talk.” Louisa hugged Rosalind. “I have a thousand things to tell you! And then there’s . . .”

“Goodness, Louisa.” Aunt Showell shook her head. “You’ll be burying Miss Thorne under your own drift!”

“Not I.” Louisa drew herself up into a stance of perfect drawing room deportment. “I’m soon to be a staid old married lady, and a banker’s wife at that. I shall have to practice being perfectly dull on someone, and Rosalind knows all about it . . . oh dear . . .” Louisa blushed, but Rosalind just laughed.

“Believe me, Louisa, I have had occasion to observe many of the finer points of dullness across the length and breadth of London. If you want to learn all the current fashions for tedium, I’ll be happy to advise. But right now, I do need to change and get myself together. Is . . . is his grace in the house?”

“Casselmaine?” cried Louisa. “Mercy, no! I don’t think he’s spent more than an hour in the house since he came down from London. He’s down at the drainage works. They’re surveying for the next canal channel, or something. He’ll tell you all about it at dinner tonight, I’m sure. Oh! Which reminds me, there will be a dinner tonight, a small one, just a few of the neighbors, and Rollins, of course.” Mr. Firth Rollins was Louisa’s betrothed. “He’s staying with the Ablehavens, but he drives over here almost every day. I can’t wait for you to meet him!” Louisa caught sight of a fresh frown from her aunt and rolled her eyes toward the distant white ceiling. “All right, all right. I’m quite finished. You rest and change, Rosalind. We’ll talk shortly.”

“If you’ll follow me, miss,” said Emerson.

Rosalind did.

Rosalind soon saw the justice in Mrs. Showell’s remarks about the hall being “inconvenient.” Once they had climbed to the second story, they left the marble foyer for corridors of polished sandstone, painted paneling, and blue carpets. Artwork lined the walls. Statuary and enameled ornaments and urns decorated nooks and tables. But the house evidently extended much farther back from the yard than Rosalind had been able to make out, and the farther they went into its depths, the darker, narrower, and more confusing the corridors became. Formerly straight lines dissolved into a bewildering series of twists and turns, not to mention rises and falls of little stairs. There were also far fewer windows, so one had the feeling of descending into the depths. The ornaments on the table were now augmented with oil lamps and candlesticks.

Emerson looked back to make sure Rosalind was keeping up.

“One soon learns the ways of the place,” she remarked.

“I keep expecting to encounter some ancestral ghost.”

“Oh, it’s all far too new for ghosts, miss. But we did misplace one of the parlor maids a week ago. We may find her yet.”

Rosalind quirked a brow. Emerson sailed ahead as if the words had never been spoken.

The door Emerson finally opened was at the far end of the corridor. Rosalind stepped into a sunny and well-aired suite of rooms all done in shades of pale green and trimmed in cream. The furnishings, in contrast to what she had seen so far, were in the simpler, modern style. A bow window complete with velvet seat graced the boudoir and overlooked an expanse of formal garden in full summer flower.

“Would you care for refreshment, miss?” Emerson asked. “I can send for tea.”

“That would be wonderful. And you’ll please let her grace, the dowager, know I’ve arrived?”

“Certainly, miss.”

Emerson gave instructions to the chambermaid and then helped Rosalind change her traveling clothes for a light, plain dress of sprigged green muslin with dark green trim.

The tea arrived and Rosalind accepted a cup. She drank while sitting on the curved window seat, simply taking a moment to enjoy the view. Unlike the awkward grandeur of the house, the gardens were truly beautiful.

A fresh knock sounded at the sitting room door. Emerson opened it to reveal Mrs. Showell standing in the corridor.

“I’m sorry to disturb you, Rosalind, but I just wanted to make sure you have everything you need.”

“You’re not disturbing me in the least.” Rosalind came out of the boudoir into the sitting room. “Won’t you join me? The tea’s just arrived.”

“Thank you.” Emerson immediately drew another chair up to the table by the hearth while Rosalind fixed Mrs. Showell a cup of tea with lemon. But she barely had time to sip before Emerson went to the door again. This time, she returned with a folded paper.

“A note for you, miss,” she said. “With her grace’s compliments.”

Mrs. Showell knitted her brows. What’s worrying her? Rosalind opened the paper given and read:

Mrs. Showell was watching her over the rim of her cup. “I suspect that is to inform you my sister will not be receiving you today.”

“Yes,” agreed Rosalind. “She asks me to come to her tomorrow.”

Mrs. Showell nodded and set her cup back down on the tray, clearly trying to arrange her thoughts, and her words. “Lady Casselmaine is not . . . very well just now.”

“I am sorry to hear it. Had I known she was ill, I would have of course delayed my visit.”

“I’m afraid my sister is quite often ill. Since Hugh died, she has become almost a complete recluse, and that is not a healthy life even for those of a most robust constitution.”

Rosalind nodded. Hugh Winterbourne had died six years before. Six years of seclusion must have an effect on the body and the spirit.

“She has her own suite of rooms and attendants, and so on, so that the household is not required to rearrange itself when one of her . . . bouts comes upon her,” Mrs. Showell went on. “And, of course, I have been performing the duties of hostess since my arrival. It does mean, however, that you will probably not be seeing much of her during your visit.”

“That would be a shame. I had been looking forward to meeting her.” Rosalind took another sip of tea and decided to risk a question. “Is it known what caused her . . . bout?”

For a moment, she thought Mrs. Showell might reply with a polite nothing. But whatever her silent thoughts were, she shook her head to clear them away. “There was a distressing event in the neighborhood some months ago now. A man of good family—one of the heroes of the Peninsular campaign in fact—was found dead. A most unfortunate accident. But when Lady Casselmaine heard . . . to her it brought back too many reminders of Hugh’s death, and she went into a state of collapse.”

“How very sad. May I know the man’s name?”

“Colonel William Corbyn. Was it possible you knew him? He was often in London.”

“No,” replied Rosalind evenly. “He was no one of my acquaintance.”

“He was a good man,” said Mrs. Showell. “A sound and a decent man. There are those who would say otherwise, but they do not get a hearing with me. He suffered much during the wars, and it left its mark, but a man should not be judged less kindly for that.”

“No, indeed,” murmured Rosalind. “Was Colonel Corbyn any relation to Helen Corbyn?”

“Her oldest brother. Is it Helen you know?”

“I don’t know her personally, but I believe Louisa has mentioned her name.”

Mrs. Showell nodded. “Probably as one of her bridesmaids. Thick as thieves the two of them are. And Helen is engaged to be married as well. At least, she was . . .” Mrs. Showell frowned at her tea.

“Did something happen?”

“Oh no. Well, probably not. But the poor girl was devastated when her brother died, and of course everything had to be put off. There was some talk it was all to be put off permanently, I believe, but time seems to have healed that wound sufficiently.”

Rosalind thought of the letter she carried in her case and privately doubted this assessment.

“I’ve met some of Louisa’s friends,” Rosalind said. “I’m surprised I have not yet met Miss Corbyn, since they are so close.”

“Well, the Corbyns were not often up to town. William himself was frequently there, but the rest of the family always kept close to home. The parents also died rather recently, which left no one to chaperone Helen through a Season. Marius, the younger brother, does not care for London social life, for all his grand ambitions.”

“What ambitions might those be?”

“He wishes to be an engineer. He talks endlessly of the great, modern world that men may build, the possibilities of gaslight and steam and I don’t know what all. I have my doubts, personally, but he is as good as a sermon when the mood is on him. Still, he’s not entirely without scope for his ambition here, thanks to Casselmaine.”

“Is Lord Casselmaine building a bridge?”

“Oh, he hasn’t told you? He’s finally talked the councils and the Lord Lieutenant round to his scheme. He’s draining the fens.”

“Oh! Yes, Louisa mentioned that.” Cassell House and the family estate were in one of the southern counties, where rolling, fertile country was bordered by long sprawls of marsh and fen. On the drive, there were moments when their driver had to occasionally navigate around the waters overflowing the ditches. In other places, the smell was so fetid, it would have done credit to some of the narrower London alleyways.

“Casselmaine’s certain getting rid of the bad airs will improve the health of the district, and of course it will open up new arable land for the farmers at a good price to compensate for recent enclosures, create room for new roads, and oh, all manner of things.” Mrs. Showell waved her hand vaguely. “He’s very dedicated about his responsibilities, you know.”

“Yes, I do know.”

Mrs. Showell grew suddenly serious. “I think it would be good for you and I to talk frankly, my dear. How do you want to manage this?”

Rosalind allowed herself a moment for a long swallow of tea and then set about refreshing her cup so she could speak without quite having to look Mrs. Showell in the eye. “I think I’m supposed to say I’m not sure what you mean, but I also think that would be condescending to us both.” She sighed. “The answer is, I don’t know.”

“Then may I offer my observations?”

“Please do.”

“Casselmaine brought you here to see if you two are still suited well enough to marry. That is obvious. It may not come off. That is the nature of these things. But, it also might. Therefore, beginning tonight, it is safest to adopt a strategy of ‘hope for the best, prepare for the worst.’”

Despite the riot of her feelings, Rosalind felt herself smile. “Which is which?”

“That is for you to decide. Until then, my advice would be that we introduce you to the neighborhood in your character as a young woman of gentle birth and possibly the new mistress of Cassell House, rather than simply as Louisa’s friend and assistant. As you know, it’s far, far easier to settle down than it is to move up.”

“And I thought the country was different from London.”

“It’s all the same people, my dear, with all the same hopes and fears. It’s just that when there’s trouble, it takes longer for those things to reach a boiling point here.”

“Since we are speaking frankly, Mrs. Showell, may I know what you think of my . . . situation?”

“I wish I could say my sister will get better and be able to resume her duties as lady of the manor so there is no need to rush into anything, especially since Casselmaine is still a young and ambitious man. But I do not think my sister will recover.” Mrs. Showell’s words turned bitter. “She has locked her own door and thrown away the key. Casselmaine needs the stability and support that come with a good marriage and heirs. Without them, he, the family, and the district will all suffer. From what I know of you, I think you could credibly turn your hand to the trade of duchess, and Casselmaine very much cares for you. Therefore, if you want my help to secure this marriage, I am willing to give it.”

Rosalind set her cup down again, but found she could not stop staring at it. Mrs. Showell said nothing she did not know, but her matter-of-fact presentation sank deeply into Rosalind’s skin.

“Thank you, Mrs. Showell,” she said, and to her shame the words came out as a hoarse whisper. “You have to forgive my . . . hesitation. I’ve spent years learning to live with the fact that I am . . . in reduced circumstances, and to treat that situation as immutable. With that came the knowledge that any sort of marriage—let alone a grand one—was impossible for me. This . . . change . . . takes some getting used to.”

“I understand perfectly,” Mrs. Showell told her. “The world is hard on those of us with . . . indifferent famil. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...