- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

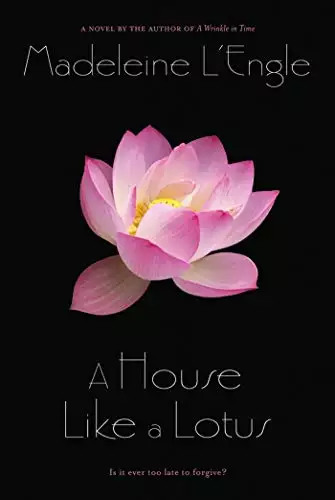

By the author of A Wrinkle in Time, the conclusion to the Polly O'Keefe stories finds Polly taking an unforgettable trip to Europe, all by herself.

Sixteen-year-old Polly is on her way to the island of Cyprus, where she will work as a gofer. The trip was arranged by Maximiliana Horne, a rich, brilliant artist who, with her longtime companion, Dr. Ursula Heschel, recently became the O'Keefe family's neighbor on Benne Seed Island. Max and Polly formed an instant friendship and Max took over Polly's education, giving her the encouragement and confidence that her isolated upbringing had not. Polly adored Max, even idolized her, until Max betrayed her. In Greece, Polly finds romance, danger, and unique friendships. But can she ever forgive Max?

Books by Madeleine L'Engle

A Wrinkle in Time Quintet

A Wrinkle in Time

A Wind in the Door

A Swiftly Tilting Planet

Many Waters

An Acceptable Time

A Wrinkle in Time: The Graphic Novel by Madeleine L'Engle; adapted & illustrated by Hope Larson

Intergalactic P.S. 3 by Madeleine L'Engle; illustrated by Hope Larson: A standalone story set in the world of A Wrinkle in Time.

The Austin Family Chronicles

Meet the Austins (Volume 1)

The Moon by Night (Volume 2)

The Young Unicorns (Volume 3)

A Ring of Endless Light (Volume 4) A Newbery Honor book!

Troubling a Star (Volume 5)

The Polly O'Keefe books

The Arm of the Starfish

Dragons in the Waters

A House Like a Lotus

And Both Were Young

Camilla

The Joys of Love

Release date: February 14, 2012

Publisher: Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Print pages: 320

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

A House Like a Lotus

Madeleine L'Engle

One

Constitution Square. Athens. Late September.

I am sitting here with a new notebook and an old heart.

Probably I'll laugh at that sentence in a few years, but it is serious right now. My sense of humor is at a low ebb.

I'm alone (accidentally) in Greece, and instead of enjoying being alone, which is a rare occurrence, since I have six younger siblings, I am feeling idiotically forlorn. Not because I'm alone but because nothing has gone as planned. What I would like to do is go back to my room in the hotel and curl up on my bed, with my knees up to my chin, like a fetus, and cry.

Do unborn babies cry?

My parents are both scientists and for a moment I am caught up in wondering about fetuses and tears. I'll ask them when I get home.

The sun is warm in Constitution Square, not really hot, but at home, on Benne Seed Island, there's always a sea breeze. Late September in South Carolina is summer, as it is in Greece, but here the air is still and thesun beats down on me without the salt wind to cool it off. The heat wraps itself around my body. And my body, like everything else, is suddenly strange to me.

What do I even look like? I'm not quite sure. Too tall, too thin, not rounded enough for nearly seventeen, red hair. What I look like to myself in my mind's eye, or in the mirror, is considerably less than what I look like in the portrait which now hangs over the piano in the living room of our house on the beach. It's been there for maybe a couple of months.

Nevertheless, it was a thousand years ago that Max said, 'I'd like to paint you in a seashell, emerging from the sea, taking nothing from the ocean but giving some of it back to everyone who puts an ear to the shell.'

That's Max. That, as well as everything else.

I've ordered coffee, because you have to be eating or drinking something in order to sit out here in the Square. The Greek coffee is thick and strong and sweet, with at least a quarter of the cup filled with gritty dregs.

I noticed some kids at a table near mine, drinking beer, and I heard the girl say that she had come to stop in at American Express to see if her parents had sent her check. "It keeps me out of their hair, while they're deciding who to marry next." And the guy with her said, "Mine would like me to come home and go to college, but they keep sending me money, anyhow."

There was another kid at the next table who was also listening to them. He had black hair and pale skin and he looked up and met my eyes, raised one silky black brow, and went back to the book he was reading. If I'd been feeling kindly toward the human race I'd have gone over and talked to him.

A group of kids, male, definitely unwashed, so maybe their checks were late in coming, looked at me but didn'tcome over. Maybe I was too washed. And I didn't have on jeans. Maybe I didn't even look American. But I had this weird feeling that I'd like someone to come up to me and say, "Hey, what's your name?" And I could then answer, "Polly O'Keefe," because all that had been happening to me had the effect of making me not sure who, in fact, I was.

Polly. You're Polly, and you're going to be quite all right, because that's how you've been brought up. You can manage it, Polly. Just try.

I'd left Benne Seed the day before at 5 a.m., South Carolina time, which, with the seven-hour time difference, was something like seventeen hours ago. No wonder I had jet lag. My parents had come with me, by Daddy's cutter to the mainland, by car to Charleston, by plane to New York and JFK airport. Airports get more chaotic daily. There are fewer planes, fewer ground personnel, more noise, longer lines, incomprehensible loudspeakers, short tempers, frazzled nerves.

But I got my seat assignment without too much difficulty, watched my suitcase disappear on the moving belt, and went back to my parents.

My father put his hands on my shoulders. 'This will be a maturing experience for you.'

Of course. Sure. I needed to mature, slow developer that I am.

Mother said, 'You'll have a wonderful time with Sandy and Rhea, and they'll be waiting for you at the airport, so don't worry.'

'I'm not worried.' Sandy is one of my mother's brothers, and my favorite uncle, and Rhea is his wife, andshe's pretty terrific, too. I'd be with them for a week, and then fly to Cyprus, to be a general girl Friday and gofer at a conference in a village called Osia Theola. I've done more traveling than most American kids, but this time, for the first time, I'd be alone, on my own, nobody holding my hand, once I left Athens.

Athens, my parents kept telling me, was going to be fun, since Rhea was born on the isle of Crete and had friends and relatives all over mainland Greece and most of the islands. Sandy and Rhea were both international lawyers and traveled a lot, and being with them was as safe as being with my parents.

Why hadn't I learned that nothing is safe?

'Write us lots of postcards,' Mother said.

'I will,' I promised. 'Lots.'

I wanted to get away from my parents, to be on my own, and yet I wanted to reach out and hold on, all at the same time.

'You'll be fine,' Daddy said.

'Sure.'

'Take care of yourself,' Mother said. 'Be happy.' Underneath her words I could almost hear her saying, 'Don't be frightened. I wish I could go with you. I wish you were a little girl again.'

But she didn't say it.

And I'm not. Not anymore. Maybe I'd like to be. But I'm not.

My family knew that something had gone wrong, that something had happened, but they didn't know what, and they respected my right not to tell them untilI was ready, or not to tell them at all. Only my Uncle Sandy knew, because Max had called him to come, and he'd flown down to Charleston from Washington. This was nothing unusual. Sandy, with or without Rhea, drops in whenever he gets a chance, popping over to the island en route to or from somewhere, just to say hello to the family.

Fortunately, I'm the oldest of our large family, including our cousin Kate, who's fourteen, living with us and going to school with us on the mainland. So no one person comes in for too much attention.

Mother put her arm around me and kissed me and there were questions in her eyes, but she didn't ask them. Flights were being called over the blurred loudspeaker. Other people were hugging and saying goodbye.

'I think that's my flight number--' I said.

Daddy gave me a hug and a kiss, too, and I turned away from them and put my shoulder bag on the moving conveyor belt that took it through the X-ray machine. I walked through the X-ray area, retrieved my bag, slung it over my shoulder, and walked on.

On the plane I went quickly to my window seat and strapped myself in. The big craft was only a little over half full, and nobody sat beside me, and that was fine with me. I wanted to read, to be alone, not to make small talk. I leaned back and listened to the announcements, which were given first in Greek, then in English. A stewardess came by with a clipboard, checking off names.

'O'Keefe. Polly O'Keefe. P-o-double l-y.' My passport has my whole name, Polyhymnia. My parents should have known better. I've learned that it's best if I spell my nickname with two l's. Poly tends to be pronounced as though it rhymes with pole. I'm tall andskinny like a pole, but even so I might get called Roly Poly. So it's Polly, two l's.

Another stewardess passed a tray of champagne. Without thinking, I took a glass. Sipped. Why did I take champagne when I didn't even want it? Not because I don't like champagne; not because I'm legally under age; but because of Max. Max and champagne, too much champagne.

At first, champagne was an icon of the world of art for me, of painting and music and poetry, with ideas fizzing even more brightly than the dry and sparkling wine. Then it was too much champagne and a mouth tasting like metal. Then it was dead bubbles, and emptiness.

I drank the champagne, anyhow. If you have a large family, you learn that if you take a helping of something, you finish it. Not that that was intended to apply to champagne, it was just an inbred habit with me. When another stewardess came by to refill my glass I said, "No, thank you."

A plane is outside ordinary time, ordinary space. High up above the clouds, I was flying away from everything that had happened, not trying to escape it, or deny it, but simply being in a place that had no connection with chronology or geography. All I could see out the window was clouds. No earth. Nothing familiar. I ate the meal which the stewardess brought around, without tasting it. I watched the movie, without seeing it. About halfway through, I surprised myself by falling asleep and sleeping till the cabin lights were turned on, and first orange juice and then breakfast were brought around. All through the cabin, people yawned and headed for the johns, and there are not enough johns, since most of the men use them for shaving.

Window shades were raised, so that sunlight flooded the cabin. While I was eating breakfast I kept peering out the window, looking down at great wild mountains. Albania, the pilot told us: rugged, dark, stony, with little sign of habitation or even vegetation.

A dark and bloody country, Max had said.

Then we flew over the Greek islands, darkly green against brilliant blue. Cyprus. After Athens, I would be going to Cyprus.

I had a sense of homecoming, because this was Europe, and although we've been on Benne Seed Island for five years, Europe still seems like home to me. Especially Portugal, and a small island off the south coast called Gaea, where the little kids were born, and where we lived till I was thirteen.

Then we moved back to the United States, to Benne Seed Island. Daddy's a marine biologist, so islands are good places for his work, and Mother helps him, doing anything that involves higher math or equations.

Being brought up on an isolated island is not good preparation for American public schools. Right from the beginning, I didn't fit in. The girls all wore large quantities of makeup and talked about boys and thought I was weird, and maybe I am. Some of the teachers liked me because I'm quick and caught up on schoolwork without any trouble, and some of them didn't like me for the same reason. I don't have a Southern accent--why should I?--so people thought I was snobby.

The best thing about school is getting to it. We all pile into a largish rowboat with an outboard motor, and running it is my responsibility. I suppose Xan's taking over while I'm away. Anyhow, we take the boat to the mainland, tie it to the dock with chain and padlock around the motor. We walk half a mile to the school bus,and then it's a half-hour bus ride. And then I get through the day, and it's bearable because I like learning things. When we lived in Portugal, there was no school on Gaea, and we were much too far from the mainland to go to school there, so our parents taught us, and learning was fun. Exciting. At school in Cowpertown, nobody seemed to care about learning anything, and the teachers cared mostly about how you scored on the big tests. I knew I had to do well on the tests, but I enjoy tests; our parents always made them seem like games. So I did well on them, and I knew that was important, because I will need to get a good scholarship at a good college. Our parents have made us understand the importance of a good education.

Seven kids to educate! Are they crazy? Sandy and Dennys will probably help, if necessary. Even so ...

Charles, next in line after me, will undoubtedly get a good scholarship. He knows more about marine biology than a lot of college graduates. He's tall--we're a tall family--and his red hair isn't as bright as mine.

Charles and I were the only ones to get the recessive red-hair gene. The others are various shades of ordinary browns.

Alexander is next, after Charles, named after Uncle Sandy, and called Xan to avoid confusion, since Sandy and Rhea come to Benne Seed so often. Xan is tall--of course--but last year he shot up, so that now he's taller than I am. It's a lot easier to boss around a little brother who's shorter than you are than one who looks over the top of your head, is a basketball star at school, is handsome, and adored by girls. We got along better when he was my little brother. He and Kate team up against the rest of us, especially me. Kate is beautiful and brown-haired and popular.

After Xan is Den, named after Uncle Dennys. He's twelve, and most of the time we get along just fine. But every once in a while he tries to be as old as Xan, and then there's trouble. At least for me.

Then come the little kids, Peggy, Johnny, and Rosy. Because I'm the oldest, I've always helped out a lot, playing with them, reading to them, giving them baths. They're still young enough to do what I tell them, and to look up to me, and to accept me just as I am. And I feel more like myself when I'm playing on the beach with the little kids than I do when I'm at school, where everybody thinks I'm peculiar.

Under normal circumstances I would have been delighted to get away from the family and from school for a month. Mother tries not to put too much responsibility on me, and everybody has jobs, but if Mother's in the lab helping Daddy work out an equation, then I'm in charge, and believe me, all these brethren and sistren have about decided me on celibacy.

The plane plunged through a bank of clouds and the stewardess called over the loudspeaker that we were all to fasten seat belts and put seats and tray tables in upright position for the descent into Athens. I kept blowing my nose to clear my ears as the pressure changed. With a minimum of bumps, we rolled along the runway. Athens.

I joined the throng leaving the plane, like animals rushing to get off the ark.

I followed the others to baggage claim and managed to get my suitcase from the carousel by shouldering my way through the crowd. As I lugged the heavy bag towardthe long counters for customs, I heard loudspeakers calling names, and hoped I might hear mine, but nobody called for Polly O'Keefe.

The customs woman peered into my shoulder bag; she could have taken it, as far as I was concerned. But I couldn't refuse the bag, which Max sent over from Beau Allaire, without someone in the family noticing and making a crisis over it. It was gorgeous, with pockets and zippers and pads and pens, and if anybody else had given it to me I'd have been ecstatic.

The customs woman pulled out one of my notebooks and glanced at it. What I wrote was obviously not in the Greek alphabet, so she couldn't have got much out of it. She handed it back to me with a scowl, put a chalk mark on my suitcase, and waved me on.

I went through the doors, looking at all the people milling about, looking for Uncle Sandy and Aunt Rhea to be visible above the crowd. I saw a tall man with a curly blond beard and started to run toward him, but he was with a woman with red hair out of a bottle (why would anybody deliberately want that color hair?), and when I looked at his face he wasn't like Sandy at all.

Aunt Rhea has black hair, shiny as a bird's wing, long and lustrous. I have my hair cut short so there'll be as little of it to show as possible. Daddy says it will turn dark, as his has done, the warm color of an Irish setter. I hope so.

Where were my uncle and aunt? I'd expected them to be right there, in the forefront of the crowd. I kept looking, moving through groups of people greeting, hugging, kissing, weeping. I even went out to the place where taxis and buses were waiting. They weren't there, either. Back into the airport. If I was certain of anythingin an uncertain world, it was that Sandy and Rhea would be right there, arms outstretched to welcome me.

And they weren't. I mean, I simply had to accept that they were not there. And I wasn't as sophisticated a traveler as I'd fooled myself into thinking I was. Someone else had always been with me before, doing the right things about passports, changing money, arranging transportation. I'd gone through passport control with no problem, but now what?

I looked at the various signs, but although I'd learned the Greek alphabet, my mind had gone blank. I could say thank you, epharisto, and please, parakalo. Kalamos means pen, and mathetes means student, and I'd gone over, several times, the phrase book for travelers Max had given me. I'm good at languages. I speak Portuguese and Spanish, and a good bit of French and German. I even know some Russian, but right now that was more of a liability than an asset, because when I looked at the airport signs I confused the Russian and Greek alphabets.

I walked more slowly, thought I saw Sandy and Rhea, started to run, then slowed down again in disappointment. It seemed the airport was full of big, blond-bearded men, and tall, black-haired women. At last I came upon a large board, white with pinned-up messages, and I read them slowly. Greek names, French, German, English, Chinese, Arabic names. Finally, P. O'Keefe.

I took the message off the board and made myself put the pin back in before opening it. My fingers were trembling.

DELAYED WILL CALL HOTEL SANDY RHEA

They had not abandoned me. Something had happened,but they had not forgotten me. I held the message in my hand and looked around the airport, where people were still milling about.

Well, I didn't need someone to hold my hand, keep the tickets, tell me what to do. I found a place where I could get one of my traveler's checks cashed into Greek money, and then got a bus which would take me to the hotel.

It was the King George Hotel, and Max had told me that it was old-fashioned and comfortable and where she stayed. If Max stayed there, then it was expensive as well as pleasant, and that made me uncomfortable. I wouldn't have minded my father paying for it, though marine biologists aren't likely to be rolling in wealth. I wouldn't even have minded Sandy and Rhea paying for it, because I knew Rhea had inherited pots of money. But it was Max. This whole trip was because of Max.

It was in August that Max had said to me, 'Polly, I had a letter today from a friend of mine, Kumar Krhishna Ghose. Would you like to go to Cyprus?'

Non sequiturs were not uncommon with Max, whose thoughts ranged from subject to subject with lightning-like rapidity.

We were sitting on the screened verandah of her big Greek revival house, Beau Allaire. The ceiling fan was whirring; the sound of waves rolled through all our words. 'Sure,' I said. 'But what's Cyprus got to do with your Indian friend?'

'Krhis is going to coordinate a conference there in late September. The delegates will be from all the underdeveloped and developing countries except those behindthe Iron Curtain--Zimbabwe, New Guinea, Baki, Kenya, Brazil, Thailand, to name a few. They're highly motivated people who want to learn everything they can about writing, about literature, and then take what they've learned back to their own countries.'

I looked curiously at Max, but said nothing.

'The conference is being held in Osia Theola in Cyprus. Osia, as you may know, is the Greek word for holy, or blessed. Theola means, I believe, Divine Speech. We can check it with Rhea. In any case, a woman named Theola went to Cyprus early in the Christian era and saw a vision in a cave. The church that was built over the cave and the village around it are named after her, Osia Theola.'

I was evidently supposed to say something. 'That's a pretty name.'

At last Max, laughing, took pity on me. 'My friend Krhis is going to need someone to run errands, do simple paperwork, be a general slave. I've offered you. Would you like that?'

Would I! 'Sure, if it's all right with my parents.'

'I don't think they'd want you to miss that kind of opportunity. Your mother can do without you for once. I'll speak to your school principal if necessary and tell him what an incredible educational advantage three weeks on Osia Theola will be. It won't be glamorous, Polly. You'll have to do all the scut work, but you're used to that at home, and I think it would be good experience for you. I've already called Krhis and he'd like to have you.'

Just like that. Three weeks at Osia Theola in Cyprus. That's how it happened. That's the kind of thing Maxcould do. Now that I thought about it, it seemed likely that Max had paid for my plane fare, too.

The week in Athens, before the conference, was something Max said I shouldn't miss, and my parents agreed. I had never been to Greece, and they were happy for me to have the opportunity.

We were all less happy about it by the time I left Benne Seed than when the plan was first talked about, Max enthusiastically showing us brochures of Athens and Osia Theola, the museums, the Acropolis. Those last weeks before I flew to Athens, my parents looked at each other when I came into a room as though they'd been talking about me, but they didn't say anything, and neither did I.

And now I was on a bus, sitting next to a family who were talking loudly in furious syllables. The man wore a red fez, so I assumed they were Turkish, and Turkish is a language I've never even attempted. During the drive I began to feel waves of loneliness, like nausea, until I was certain the hotel wouldn't have a reservation for me, and what then? I certainly wasn't going to call South Carolina and ask someone to come rescue me.

But I was welcomed, personally, by the manager, and given a message which said the same thing as the one at the airport.

I liked the hotel, which reminded me a little of hotels in Lisbon. But I felt very alone. I followed the bellman to my room. He opened the door, put my bag down on the rack, flung open doors to closets, to a big bathroom, opened floor-length windows to the balcony.

"Acropolis," he said, pointing to the high hill with its ancient, decaying buildings, and I caught my breath at the beauty. Sounds of the present came in, contradicting the view: bus brakes, taxi horns, the wail of a siren.I stood looking around, first at the view, then at the room, which was comfortably European, with yellow walls, a brass bed, a stained carpet, and an enormous bouquet of mixed flowers on a low table in front of the sofa.

After a moment I realized that I'd forgotten the bellman and that he was waiting, so I dug in my purse for what I hoped was the right amount of money, put it in his hand, saying, "Epharisto."

He checked what I'd given him, smiled at me in approval, said, "Parakalo," and left, closing the door gently behind him.

The sunlight flooded in from the balcony, warming me. Despite the heat, I felt an odd kind of cold, like numbness from shock. I unpacked, spreading out notebooks and paperbacks on the coffee table to establish my territorial imperative. No photographs. Not of anybody.

Whenever I stepped out of the direct sunlight, the inner cold returned. And a dull drowsiness. Although I had slept more on the plane than I had expected, it was a long time since I'd actually stretched out on a bed. The early-afternoon sun was streaming across the balcony and into my room, but my internal time clock told me I was tired and wanted to go to bed.

Max had suggested that I get on Greek time as soon as possible. 'Take a nap when you get to the hotel, but not a long one. Here.' And I was handed a small travel alarm. 'I won't be needing this anymore, and it weighs hardly anything. Sleep for a couple of hours after you arrive, and then go to bed on Greek time. It'll be easier in the long run.'

I didn't want Max's alarm clock, and I didn't want Max's advice, no matter how excellent. If it hadn't been for the telephone, I'd have gone right out, defiantly, andwandered around Athens. But I couldn't do anything until I'd heard from Sandy and Rhea.

'Do you still love me?' Sandy had asked.

'Of course I do.'

'It was I who introduced you to Max.'

'I know,' I had said.

It all seemed a very long time ago. And yet it was right here in the present. I had crossed an ocean and still I couldn't get away from it.

The sunlight fell on the bed. I stretched out in its warmth, lying on my side so that I could see the Acropolis. I looked across twentieth-century Athens, across hundreds of years to a world long gone. To the people who lived way back when the Parthenon was built, who worshipped the goddess Athena, what had happened to me wouldn't be very cosmic. To the other people in the hotel, also maybe looking out their windows from the present to the past, it wouldn't seem very important, either.

'It's all right.' Sandy had his arms about me. 'You have to go all the way through your feelings before you can come out on the other side. But don't stay where you are, Polly. Move on.'

There was a knock on the door, and I realized I had been hearing Sandy's voice in a half dream. I sat up.

"Who is it?"

"Some fruit, and a letter for Miss O'Keefe."

I opened the door to a young uniformed man who bore a large basket of fruit, which he put down on the dresser. "With the compliments of the manager." He handed me an envelope. "We neglected to give you this when you arrived."

"Epharisto." I shut the door on him and ripped open the envelope. One page, in the familiar, strong, darkhandwriting. "Polly, my child, take this week in Athens in the spirit in which it is given. Forgive me and love me. Max."

I crumpled up the letter. Flung it at the wastepaper basket. The phone jangled across my thoughts.

It was Sandy, sounding as close as when he called at home, ringing South Carolina from Washington.

"Polly, you're there!"

"Sandy, where are you? What happened?"

"Still in Washington. An emergency. Sorry, Pol, but in my line of work you know these things do happen."

His work has more to it than meets the eye. He and Rhea don't just work with big corporations and their international deals. It's top-secret kind of stuff, but I know it has something to do with seeing that underdeveloped nations don't get ripped off, and when tensions rise in the Middle East or South America or Africa they're often sent there to ease things. Rhea and Mother are close friends, and I have a hunch she tells Mother a good bit, but the most I've ever got out of Mother was an ambiguous 'They're on the side of the angels.'

I said to Sandy, "I know these things happen, but are you going to come?"

"Of course we're coming. I'll be dug out by Monday night, with Rhea's help, and we've changed our flight to Tuesday. We should be with you in plenty of time for dinner, three days from now. Will you be all right?"

"Sure," I said without much conviction. But Sandy always makes me feel that I can manage anything, and I didn't want to let him down. "Do Mother and Daddy know?"

"Do you want them to?" he asked. It was a challenge.

I accepted it. "No. They might worry." Funny. We've been given a lot of independence in many ways, we'vehad more experience than a lot of kids, and yet we're also in some ways very overprotected. They would worry.

"Do you have enough money?" he asked.

"Max gave me three hundred dollars in traveler's checks. Daddy gave me two hundred. I'm rolling in wealth."

"Good. Don't blow it all the first day. But make a reservation on the roof restaurant of your hotel tonight, and just sign for your dinner. There's a superb view."

"There's a superb view from my room," I said. "I can see the Parthenon."

"Good. Max is an old friend of the manager. I knew you'd get one of the best rooms."

"It's very European and comfortable. Sandy, it's got to be expensive."

"Forget it," he said briskly. "It's peanuts to Max. Check with the concierge and get yourself a ticket for a bus tour or two and see the sights. Don't waste these days till Rhea and I join you."

"I won't. I'm not a waster, you know that."

"That's my Pol. You all right?"

"I'm fine," I said, which meant, I accept your challenge, Sandy. I'll be fine in Athens on my own. I'm not a child.

"See you Tuesday," he said. "I love you, Polly."

"I love you, too. See you."

When we hung up, I lay down on the bed, fighting the tears which Sandy's voice had brought rushing to my eyes. Sandy believes that things have meaning, that there are no coincidences, so I had to suppose there was some meaning to his being detained in Washington. Maybe it was to knock my pride down, to remind me that I might have seen a good bit of the world but I'd never been completely on my own before.

I went into the bathroom and took a hot, soaky bath; wrapped myself in two large, thick towels and sat at the open window to dry and look at the view. In the distance the Acropolis and the bright stones of the Parthenon were dazzling. In the foreground were the streets of Athens, with tropical trees which reminded me of home.

When I was dry I put on a cool cotton skirt and top and looked at my watch, which I'd changed to Greek time on the plane. Just after 2 p.m. I went to the balcony again to set myself in time and space.

The great city was spread out before me. And I wondered: What do the old gods, the heroes in the Iliad and the Odyssey, think of the cars and buses and gas-and-oil-smelling streets of today, or the modern hi-rise buildings going down to the harbor and stretching up the mountainsides? Piraeus, the port, and Athens are one vast city. In the days of Homer, what did all this look like? Were there great plains between the city and the harbor?

I went down to the lobby and made a reservation for dinner on the roof. The restaurant didn't open till eight, and the concierge looked at me as though he thought I was gauche when I asked for an eight o'clock reservation, so I put on my most aloof look and told him that I had jet lag and wanted to get to bed at a reasonable hour, which, after all, was true. Then I checked on Sandy and Rhea's reservation, and of course they'd already taken care of changing it. I asked about tours, but there were so many I decided I was too tired to cho

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...