- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

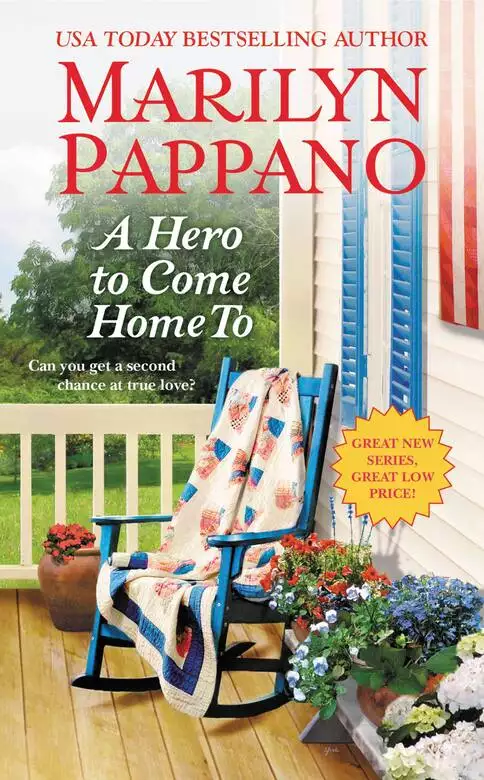

Synopsis

Publisher's Weekly named this stunning novel one of the BEST BOOKS OF 2013! First he fought for his country. Now he'll fight for her.

Two years after losing her husband in Afghanistan, Carly Lowry has rebuilt her life in Tallgrass, Oklahoma. She has a job she loves teaching third grade and the best friends in the world: fellow military wives who understand what it means to love a man in uniform. She's comfortable and content...until she meets a ruggedly handsome stranger who rekindles desires Carly isn't quite sure she's ready to feel.

Staff Sergeant Dane Clark wanted to have a loving family, a twenty-year Army stint, and then a low-key civilian career. But the paratrooper's plans were derailed by a mission gone wrong. Struggling to adjust to his new life, he finds comfort in the wide open spaces of Tallgrass--and in the unexpected attention of sweet, lovely Carly. She is the one person who makes him believe life is worth living. But when Carly discovers he's been hiding the real reason he's come to Tallgrass, will Dane be able to convince her he is the hero she needs?

Release date: June 25, 2013

Publisher: Forever

Print pages: 279

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

A Hero to Come Home To

Marilyn Pappano

Thirteen months, two weeks, and three days.

That was the first conscious thought in Carly Lowry’s head when she opened her eyes Tuesday morning. It was like an automatic tote board, adding each day to the total whether she wanted it to or not.

Thirteen months, two weeks, and three days. The way she marked her life now. There weren’t events or occasions, no workdays or weekends, holidays or seasons. This was the only important passage of her time.

Thirteen months, two weeks, and three days since the helicopter transporting Jeff had been shot down in Afghanistan. Since her own life had ended. Her stubborn body just didn’t recognize it.

Closing her eyes again, she groped for the remote on the nightstand and hit the power button. The morning news was on, though she paid it little mind. She didn’t care about the latest bank robbery in Tulsa, or the sleazy lawyer’s newest excuse to keep his high-profile client out of court on homicide charges, or which part of the city had construction woes adding to their morning commute.

Here in Tallgrass, Oklahoma, none of those things had happened in a long time. It was a great place to raise kids, Jeff had told her when they’d transferred here. Low crime rate, affordable cost of living if they discounted the air-conditioning bill in the dog months of summer, and all the amenities of Fort Murphy right next door. He’d loved downtown, with its stately buildings of sandstone and brick, none taller than three stories, as solid as if they’d grown right up out of the soil. He’d liked the old-fashioned awnings over the shop windows and the murals of cowboys, buffalo, and oil rigs painted on the sides of some of those buildings, along with restored eighty-year-old ads, back when phone numbers had only three digits. He’d loved the junk stores, where detritus of past lives showed up, their value and sometimes even their purpose forgotten. Rusty faded pieces of the town’s history.

He’d loved her. Promised their time in Tallgrass would be good. Promised that when he retired from the Army, they would settle in just such a little town to finish raising their kids and turn gray and creaky together.

He’d broken his promise.

A sob escaped her, though she pretended it was a yawn and threw back the covers as if sleep might entice her if she remained in bed one minute longer. Truth was, crying every night wasn’t conducive to a good night’s sleep.

She avoided looking in the mirror as she got into the shower. She knew she had bed head, her pajamas made no attempt whatsoever at style, and her eyes were red and puffy. When she got out ten minutes later, she concentrated on the tasks of getting dried, dressed, and made up instead of the signs of tears, the fourteen pounds she’d gained, and the simple platinum band on her left hand.

She was ready for work early. She always was. While a cup of coffee brewed in the sleek machine she had bought as a surprise after Jeff had coveted it at the PX, she opened the refrigerator, then the pantry, looking for something to eat. She settled, as she did every morning, on oatmeal labeled as a “weight-control formula.” She ate it for the protein, she told herself, because she needed the energy at work, and not because those fourteen pounds were huddled stubbornly on her hips and plotting to become twenty. To help them along, she added creamer and real sugar to her coffee, then topped off the meal with two pieces of rich, chocolate-covered caramel.

It was still too early for work, but too late to stay in the house any longer. After making sure the papers she’d graded the night before were inside her soft-sided messenger bag—of course they were—she stuffed her purse in, too, before grabbing her keys and heading outside to the car.

It was a chilly morning, but she didn’t dash back in for a jacket. A utilitarian navy-blue one was tossed across the passenger seat. Since college, she’d kept one in the car for cold restaurants, not that she ate out much anymore. Eating alone was bad enough; doing it in public exceeded her capabilities.

Two miles stretched out between her neighborhood and the Fort Murphy gate, then less than another to the post’s school complex where she taught. Most soldiers reported for duty an hour or more before school started, so she could wait that much longer at home and make the trip in less time, but moping was as well done in the car as at home.

She moved into the long double-lane line turning off Main Street and into the post. The only traffic jams Tallgrass ever saw were outside the fort’s two main gates in the morning and afternoon. Jeff had liked to go to work early and stay late because life was too damn fun to sit idle in traffic.

He’d never sat idle.

Finally it was her turn to show her license and proof of insurance to the guard at the gate, who waved her through with a courteous, “Have a good day, ma’am.”

Oh, yeah. Her days were so good, she wasn’t sure how many more of them she could handle.

“You need to talk to someone,” her sister-in-law had advised her in last week’s phone call.

“To who? I’ve talked to the grief counselors and the chaplain, I’ve talked to you, I’ve even tried to talk to Mom.” Carly’s voice had broken on that.

Lisa’s voice had turned sympathetic. “You know your mom doesn’t ‘get’ emotional.”

A thin smile curled her lips as she turned into the parking lot for the schools. None of her family “got” emotional. Mom, Dad, and three brothers: scientists, every last one of them. Logical, detached, driven by curiosity and rationale and great mysteries to solve. Unfortunately, she, with her overload of emotion, wasn’t the right sort of mystery for them. They were sympathetic—to a point. Understanding—to a point. Beyond that, though, she was more alien to them than the slide samples under their microscopes.

Easing into a parking space, she cut off the engine. Large oaks, with last fall’s brown leaves waiting to be pushed aside by this spring’s new ones, shaded the U-shaped complex. She worked in the one ahead of her, the elementary school; the middle school was, appropriately, in the middle; and the high school stood across the vast lot behind her.

Only two other employees had beaten her: one of the janitors and the elementary principal. He was a nice guy who always came early—problems of his own to escape at home, or so the gossips said—and brought pastries and started the coffee in the teachers’ lounge. He was about her father’s age, but much more human. He understood emotion.

Still, she didn’t open her car door, even when the chill crept over her as the heater’s warmth dissipated. The comment about her mother hadn’t been the end of her conversation with Lisa. Her sister-in-law had returned to the subject without missing a beat. “You need to talk to someone who’s been there, Carly. Someone who really, truly knows what it’s like. Another wife.”

Lisa couldn’t bring herself to use the word widow, not in reference to Carly. Carly couldn’t, either.

“I don’t know…” She could have finished it several ways. I don’t know if I want to talk to anyone. I’m all talked out. Or I don’t know if talking could possibly help. It hasn’t yet. Or I don’t know any other wives whose husbands have died.

But that wasn’t true. Wives—widows—didn’t tend to stay in the town where their husbands had last been assigned. They usually had homes or families to return to. But she knew one who hadn’t left: Therese Matheson. Well, she didn’t actually know her, other than to say hello. Therese’s kindergartners were on recess and at lunch at different times than Carly’s third-graders, and their free periods didn’t coincide, either.

But Therese had been there, done that and had the flag and posthumous medals to show for it. Therese really, truly knew. Would it hurt to ask if they could meet for dinner one evening? One dinner wasn’t much of a commitment. If it didn’t pan out, so what? At least she would have eaten something besides a frozen entrée or pizza.

Therese would be at school before the eight-fifteen bell. Carly would find out then.

“Tuh-reese, where’s my pink shirt?”

Thirteen-year-old Abby’s voice had always had a shrill edge, from the first time Therese Matheson had met her, but it had grown even worse over the past months. It was designed to get on her nerves quicker than a classful of kindergartners who’d had too much sugar, too much whine, and not enough rest.

“Tuh-race,” she murmured for the thousandth time before raising her voice enough to be heard upstairs. “If it’s not in your closet, Abby, then it’s in the laundry.”

Footsteps reminiscent of a Jurassic Park T. Rex resounded overhead, then Abby appeared at the top of the stairs. She was barely a hundred and ten pounds. How could she make such noise? “You mean you didn’t wash it?”

Therese bit back the response that wanted to pop out: How many times have I told you? Instead, keeping her tone as normal as possible, she said, “You know the policy. If it’s not in the hamper, it’s not going to make it to the washer.”

The girl’s entire body vibrated with her frustration. “Oh God, the one day a week we don’t have to wear our uniforms and we all decided to wear pink today, and now I can’t because you can’t be bothered to do your job! My mom always…” The words faded as she whirled, her pale blond and scarlet hair flouncing, and stomped back to her room.

Your job. Therese leaned against the door frame. Being a mother was work, sure, tumultuous and chaotic, absolutely, but it wasn’t supposed to be a job. It was supposed to be balanced by love and affection, common courtesy and respect. While their little family had an overabundance of tumult and chaos and resentment and hostility, there was precious little of the good things that made the rest worthwhile.

“Oh, Paul,” she whispered, her gaze shifting to the framed photo above the fireplace. “You were the glue that held us together. Now that you’re gone, we’re falling apart. I’m trying, I really am, but…” Her voice broke, and tears filled her eyes. “I don’t think I can do this without you.”

For as long as she could remember, she’d wanted a husband and children, and for the last six years, she’d wanted Paul’s children—sweet babies with his ready smile, his good nature and sense of humor, his endless capacity to love.

She’d gotten his children, all right. Just not in the way she’d expected.

A distant rumble penetrated her sorrow, and her gaze flickered to the wall clock. She blinked away the moisture, cleared the lump from her throat and called, “Jacob! The bus is coming.”

Again heavy steps pounded overhead, then her tall, broad-shouldered stepson took the stairs three at a time. Only eleven, he was built like his father and shared the same coloring—dark blond hair, fair skin, eyes like dark chocolate—but that was where the similarities ended. Where Paul had been warm and funny and considerate, Jacob was moody and distant. Paul had been easy to get along with; Jacob was prickly.

Not that he wasn’t entitled—rejected by his mother and abandoned, however unwillingly, by his father. Therese tried to be there for him, to talk to him, to comfort him, and God knew how often she prayed for him. But the last time he’d let her hug him had been right after Paul’s funeral fifteen months ago. It seemed the harder she tried, the harder he pushed her away.

He paused only long enough to grab the backpack in the living room, then the door slammed behind him. He didn’t say good-bye, didn’t even glance her way.

Therese tried to take a calming breath, but her chest was tight, her lungs so compressed that only a fraction of the air she needed could squeeze through. In the beginning, right after she’d gotten the news of Paul’s death, the difficulty breathing, the clamminess, the fluttering just beneath her breastbone, had been an occasional thing, but over the months it had come more often.

People asked her how she was doing, and she gave them phony smiles and phony answers, and everyone believed her, even her parents. She was afraid to tell the truth: that every day was getting worse, that she was losing ground with the kids, that her stomach hurt and her chest hurt and her head was about to explode. She did her best to maintain control, but she was only pretending. Whatever control she had was fragile and, worse, sometimes she wanted to lose it. To shatter into nothingness. After all, nothing couldn’t be hurt, couldn’t suffer, couldn’t grieve. Nothing existed in a state of oblivion, and some days—most days lately—she needed the sweet comfort of oblivion.

Another rumble cut through the rushing in her ears, and she forced her mouth open, forced Abby’s name to form. Unlike Jacob, Abby didn’t ignore her but glared at her all the way down the stairs. Contrary to her earlier shriek, she was wearing pink: a silk blouse from Therese’s closet. It was too big for her, so she’d layered it over a torso-hugging tank top and tied the delicate fabric into knots at her waist.

Abby’s defiant stare dared Therese to comment. Just as defiant, she ground her teeth and didn’t say a word. She had splurged on the blouse for a date night with Paul, but no way she would wear it again now. If it was even salvageable after a day with the princess of I-hate-you.

The door slammed, the sudden quiet vibrating around Therese, so sharp for a moment that it hurt. The house was empty. She was empty.

Dear God, she needed help.

She just didn’t know where to get it.

As the warning bell rang, Carly left her class in the capable hands of her aide and made her way to the kindergarten wing that stood at a right angle to her own wing. Therese Matheson’s classroom was at the end of the hallway, next to a door that led to the playground. It was large and heavy, especially compared to the five-year-olds that populated the hall, but since five-year-olds were proven escape artists, it was wired with an alarm to foil any attempts.

Therese stood in the hallway, greeting her students, ushering the stragglers into the room. Pretty, dark haired, she looked serene. Competent. So much more in control of herself than Carly. For a moment, Carly hesitated, unsure about her plan. What could she possibly have to offer Therese?

Then she squared her shoulders, fixed a smile on her face and approached her. “Hi, Therese, I’m Carly Lowry. Third grade?” One hand raised, thumb pointing back the way she’d come. “I, uh…My husband was…”

Sympathy softened Therese’s features even more. “I know. Mine, too.”

A pigtailed girl darted between them, pausing long enough to beam up, revealing a missing tooth. “Hi, Miss Trace.”

“Good morning, Courtney.” Therese touched her lightly on the shoulder before the girl rushed inside.

Kindergartners were unbearably cute, but Carly couldn’t have taught them. That young and sweet and cuddly, they would have been a constant reminder of the kids she and Jeff had planned to have. Would never have.

“I was, uh, wondering…well, if you would mind getting together for dinner one night to—to talk. About…our husbands and, uh, things. If…well, if you’re interested.”

Therese considered it, raising one hand to brush her hair back. Like Carly, she still wore her wedding ring. “I’d like that. Does tonight work you?”

Carly hadn’t expected such a quick response, but it wasn’t as if she had any other demands on her time. And if she had too much time to think about this idea, she very well might back out. “Sure. Is Mexican all right?”

Therese smiled. “I haven’t had a margarita in months. The Three Amigos?”

It was Tallgrass’s best Mexican restaurant, one of Jeff’s favorites. Because of that, the only Mexican food Carly had since he died had been takeout from Bueno. “That would be great. Does six work for you?”

Therese’s smile widened. “I’ll be there.”

The bell rang, the last few kids in the hall scurrying toward their classes. Carly summoned her own smile. “Good. Great. Uh, I’ll see you tonight.”

An unfamiliar emotion settled over her as she walked back to her own classroom. Hope, she realized. For the first time in thirteen months, two weeks, and three days, she felt hopeful. Maybe she could learn how to live without Jeff, after all.

Chapter One

One year later

It had taken only three months of living in Oklahoma for Carly to learn that March could be the most wonderful place on earth or the worst. This particular weekend was definitely in the wonderful category. The temperature was in the midseventies, warm enough for short sleeves and shorts, though occasionally a breeze off the water brought just enough coolness to chill her skin. The sun was bright, shining hard on the stone and concrete surfaces that surrounded them, sharply delineating the new green buds on the trees and the shoots peeking out from the rocky ground.

It was a beautiful clear day, the kind that Jeff had loved, the kind they would have spent on a long walk or maybe just lounging in the backyard with ribs smoking on the grill. There was definitely a game on TV—wasn’t it about time for March Madness?—but he’d preferred to spend his time off with her. He could always read about the games in the paper.

Voices competed with the splash of the waterfall as she touched her hand to her hip pocket, feeling the crackle of paper there. The photograph went everywhere with her, especially on each new adventure she took with her friends. And this trip to Turner Falls, just outside Davis, Oklahoma, while tame enough, was an adventure for her. Every time she left their house in Tallgrass, two hours away, was an adventure of sorts. Every night she went to sleep without crying, every morning she found the strength to get up.

“There’s the cave.” Jessy, petite and red haired, gestured to the opening above and to the right of the waterfall. “Who wants to be first?”

The women looked around at each other, but before anyone else could speak up, Carly did. “I’ll go.” These adventures were about a lot of things: companionship, support, grieving, crying, laughing, and facing fears.

There was only one fear Carly needed to face today: her fear of heights. She estimated the cave at about eighty feet above the ground, based on the fact that it was above the falls, which were seventy-two feet high, according to the T-shirts they’d all picked up at the gift shop. Not a huge height, so not a huge fear, right? And it wasn’t as if they’d be actually climbing. The trail was steep in places, but anyone could do it. She could do it.

“I’ll wait here,” Ilena said. Being twenty-eight weeks pregnant with a child who would never know his father limited her participation in cave climbing. “Anything you don’t want to carry, leave with me. And be sure you secure your cameras. I don’t want anything crashing down on me from above.”

“Yeah, everyone try not to crash down on Ilena,” Jessy said drily as the women began unloading jackets and water bottles on their friend.

“Though if you do fall, aim for me,” Ilena added. “I’m pretty cushiony these days.” Smiling, she patted the roundness of her belly with jacket-draped arms. With pale skin and white-blond hair, she resembled a rather anemic snowman whose builders had emptied an entire coat closet on it.

Carly faced the beginning of the trail, her gaze rising to the shadow of the cave mouth. Every journey started with one step—the mantra Jeff had used during his try-jogging-you’ll-love-it phase. She hadn’t loved it at all, but she’d loved him so she’d given it a shot and spent a week recovering from shocks such as her joints had never known.

One step, then another. The voices faded into the rush of the falls again as she pulled herself up a steep incline. She focused on not noticing that the land around her was more vertical than not. She paid close attention to spindly trees and an occasional bit of fresh green working its way up through piles of last fall’s leaves. She listened to the water and thought a fountain would be a nice addition to her backyard this summer, one in the corner where she could hear it from her bedroom with the window open.

And before she realized it, she was squeezing past a boulder and the cave entrance was only a few feet away. A triumphant shout rose inside her and she turned to give it voice, only to catch sight of the water thundering over the cliff, the pool below that collected it and Ilena, divested of her burden now and calling encouragement.

“Oh, holy crap,” she whispered, instinctively backing against the rough rock that formed the floor of the cave entrance.

Heart pounding, she turned away from the view below, grabbed a handful of rock and hauled herself into the cave. She collapsed on the floor, unmindful of the dirt or any crawly things she might find inside, scooted on her butt until the nearest wall was at her back, then let out the breath squeezing her chest.

Her relieved sigh ended in a squeak as her gaze connected with another no more than six feet away. “Oh, my God!” Jeff’s encouragement the first time she’d come eye to eye with a mouse echoed in her head: “He’s probably as scared of you as you are of him.”

The thought almost loosed a giggle, but she was afraid it would have turned hysterical. The man sitting across the cave didn’t look as if he were scared of anything, though that might well change when her friends arrived. His eyes were dark, his gaze narrowed, as if he didn’t like his solitude interrupted. It was impossible to see what color his hair was, thanks to a very short cut and the baseball cap he wore with the insignia of the 173rd Airborne Brigade Combat Team. He hadn’t shaved in a day or two, and he was lean, long, solid, dressed in a T-shirt and faded jeans with brand-new running shoes.

He shifted awkwardly, sliding a few feet farther into the cave, onto the next level of rock, then ran his hands down his legs, smoothing his jeans.

Carly forced a smile. “I apologize for my graceless entrance. Logically, I knew how high I was, but as long as I didn’t look, I didn’t have to really know. I have this thing about heights, but nobody knows”—she tilted her head toward the entrance where the others’ voices were coming closer—“so I’d appreciate it if you didn’t say anything.”

Stopping for breath, she grimaced. Apparently, she’d learned to babble again, as if she hadn’t spoken to a stranger—a male stranger, at least—in far too long. She’d babbled with every man she’d met until Jeff. Though he’d been exactly the type to intimidate her into idiocy, he never had. Talking to him had been easy from the first moment.

“I’m Carly, and I hope you don’t mind company because I think the trail is pretty crowded with my friends right now.” She gestured toward the ball cap. “Are you with the Hundred Seventy-Third?”

There was a flicker of surprise in his eyes that she recognized the embroidered insignia. “I was. It’s been a while.” His voice was exactly what she expected: dark, raspy, as if he hadn’t talked much in a long time.

“Are you at Fort Sill now?” The artillery post at Lawton was about an hour and a half from the falls. It was Oklahoma’s only other Army post besides Fort Murphy, two hours northeast at Tallgrass.

“No.” His gaze shifted to the entrance when Jessy appeared, and he moved up another level of the ragged stone that led to the back of the shallow cave.

“Whoo!” Jessy’s shout echoed off the walls, then her attention locked on the man. The tilt of her green eyes gave her smile a decided feline look. “Hey, guys, we turn our back on her for one minute, and Carly’s off making new friends.” She heaved herself into the cave and, though there was plenty of room, nudged Carly toward the man before dropping to the stone beside her. She leaned past, offering her hand. “Hi, I’m Jessy. Who are you?”

Carly hadn’t thought of offering her hand or even asking his name, but direct was Jessy’s style, and it usually brought results. This time was no different, though he hesitated before extending his hand. “I’m Dane.”

“Dane,” Therese echoed as she climbed up. “Nice name. I’m Therese. And what are you doing up here in Wagon Wheel Cave?”

“Wishing he’d escaped before we got here,” Carly murmured, and she wasn’t sure but thought she heard an agreeing grunt from him.

The others crowded in, offering their names—Fia, Lucy, and Marti—and he acknowledged each of them with a nod. Somewhere along the way, he’d slipped off the ball cap and pushed it out of sight, as though he didn’t want to advertise the fact that he’d been Airborne. As if they wouldn’t recognize a high-and-tight haircut, but then, he didn’t know he’d been cornered by a squad of Army wives.

Widows, Carly corrected herself. They might consider the loose-knit group of fifteen to twenty women back in Tallgrass just friends. They might jokingly refer to themselves as the Tuesday Night Margarita Club, but everyone around Tallgrass knew who they really were, even if people rarely said the words to them.

The Fort Murphy Widows’ Club.

Marti, closest to the entrance, leaned over the edge far enough to make Carly’s heart catch in her chest. “Hey, Ilena, say hi to Dane!”

“Hello, Dane!” came a distant shout.

“We left her down below. She’s preggers.” At Dane’s somewhat puzzled gesture, Marti yelled out again, “Dane says hi!”

“Bet you’ve never been alone in a small cave with six women,” someone commented.

“Hope you’re not claustrophobic,” someone else added.

He did look a bit green, Carly thought, but not from claustrophobia. He’d found the isolation he was seeking, only to have a horde of chatty females descend on him. But who went looking for isolation in a public park on a beautiful warm Saturday?

Probably lots of people, she admitted, given how many millions of acres of public wilderness there were. But Turner Falls wasn’t isolated wilderness. Anyone could drive in. And the cave certainly wasn’t isolated. Even she could reach it.

Deep inside, elation surged, a quiet celebration. Who knew? Maybe this fall she would strap into the bungee ride at the Tulsa State Fair and let it launch her into the stratosphere. But first she had to get down from here.

Her stomach shuddered at the thought.

After a few minutes’ conversation and picture taking, her friends began leaving again in the order in which they’d come. With each departure, Carly put a few inches’ space between her and Dane until finally it was her turn. She took a deep breath…and stayed exactly where she was. She could see the ground from here if she leaned forward except no way was she leaning forward with her eyes open. With her luck, she’d get dizzy and pitch out headfirst.

“It’s not so bad if you back out.” Despite his brief conversation with the others, Dane’s voice still sounded rusty. “Keep your attention on your hands and feet, and don’t forget to breathe.”

“Easy for you to say.” Her own voice sounded reedy, unsteady. “You used to jump out of airplanes for a living.”

“Yeah, well, it’s not the jumping that’s hard. It’s the landing that can get you in a world of trouble.”

On hands and knees, she flashed him a smile as she scooted in reverse until there was nothing but air beneath her feet. Ready to lunge back inside any instant, she felt for the ledge with her toes and found it, solid and wide and really not very different from a sidewalk, if she discounted the fact that it was eighty feet above the ground. “You never did say where you’re stationed,” she commented.

“Fort Murphy. It’s a couple hours away—”

“At Tallgrass.” Her smile broadened. “That’s where we’re all from. Maybe we’ll see you around.” She eased away from the entrance, silently chanting to keep her gaze from straying. Hands, feet, breathe. Hands, feet, breathe.

Dane Clark stiffly moved to the front of the cave. A nicer guy would’ve offered to make the descent with Carly, but these days he found that being civil was sometimes the best he could offer. Besides, he wasn’t always steady on his feet himself. If she’d slipped and he’d tried to catch her, she likely would have had to catch him instead. Not an experience his ego wanted.

His therapists wouldn’t like it if they knew he was sitting in this cave. He’d only been in Tallgrass a few days. The first day, he’d bought a truck. The second, he’d come here. The drive had been too long, the climb too much. But he’d wanted this to be the first thing he’d done here because . . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...