- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

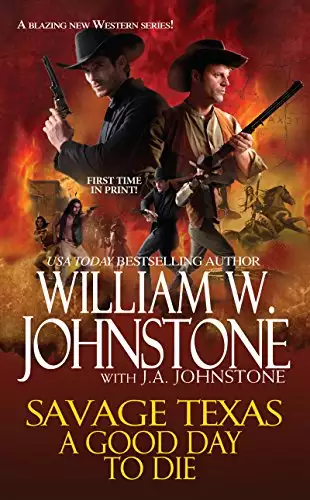

The Greatest Western Writer Of The 21st Century

The novels of William Johnstone and J.A. Johnstone have set the standard for hard-hitting Western fiction. In his new series, this master storyteller trains his sights on Texas--and the men and women who sowed their sweat and blood into the land.

A Good Day To Die

In Hangtree, Texas, any day could be your last. For on the heels of the Civil War, Hangtree is drawing gamblers, fast women and faster gunmen. Amidst the brawls and shooting, the land-grabbing and card-sharking, two men barely hold the boomtown together: Yankee Sam Heller and Texan Johnny Cross. Heller and Cross can't stand the sight of each other. And Hangtree needs them more than ever.

A Comanche named Red Hand leads a horde of warriors on a horrific path of bloodshed and destruction, with Hangtree sitting right in Red Hand's path. For a town bitterly divided, for Heller and Cross, the time has come to unite and stand shoulder to shoulder--and fight, live or die for their little slice of heaven called Hangtree.

The novels of William Johnstone and J.A. Johnstone have set the standard for hard-hitting Western fiction. In his new series, this master storyteller trains his sights on Texas--and the men and women who sowed their sweat and blood into the land.

A Good Day To Die

In Hangtree, Texas, any day could be your last. For on the heels of the Civil War, Hangtree is drawing gamblers, fast women and faster gunmen. Amidst the brawls and shooting, the land-grabbing and card-sharking, two men barely hold the boomtown together: Yankee Sam Heller and Texan Johnny Cross. Heller and Cross can't stand the sight of each other. And Hangtree needs them more than ever.

A Comanche named Red Hand leads a horde of warriors on a horrific path of bloodshed and destruction, with Hangtree sitting right in Red Hand's path. For a town bitterly divided, for Heller and Cross, the time has come to unite and stand shoulder to shoulder--and fight, live or die for their little slice of heaven called Hangtree.

Release date: October 24, 2011

Publisher: Pinnacle Books

Print pages: 449

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Close

A Good Day to Die

William W. Johnstone

On a night in late May 1866, Comanche Chief Red Hand took up the Fire Lance to proclaim the opening of the warm weather raiding season—a time of torture, plunder, and murder. For warlike Comanche braves, the best time of the year.

Six hundred and more Comanche men, women, and children were camped near a stream in a valley north of the Texas panhandle, on land between the Canadian and Arkansas rivers. The site, Arrowhead Rock, lay deep in the heart of the vast, untamed territory of Comancheria, home grounds of the tribal nation.

The gathering was made up mostly of two main subgroups, the Bison Eyes and the Dawn Hawks, along with a number of lesser clans, relations, and allies.

Red Hand, a Bison Eye, was a rising star who had led a number of successful raids in recent seasons past. Many braves, especially those of the younger generation, were eager to attach themselves to him.

Others had come to hear him out and make up their own minds about whether or not to follow his lead. Not a few had come to keep a wary eye on him and see what he was up to.

All brought their families with them, from the oldest squaws to the youngest babes in arms. They brought their tipis and personal belongings, horse herds, and even dogs.

The Comanche were a mobile folk, nomads who followed the buffalo herds across the Great Plains. They spent much of their lives on horseback and were superb riders. They were fierce fighters, arguably the most dangerous Indian tribe in the West. They gloried in the title of Lords of the Southern Plains.

Farther southwest—much farther—lay the lands of the Apache, relentless desert warriors of fearsome repute. During their seasonal wanderings Comanches raided Apaches as the opportunity presented itself, but the Apache did not strike north to raid Comancheria. This stark fact spoke volumes about the relative deadliness of the two.

The camp on the valley stream was unusual in its size, the tribesmen generally preferring to travel in much smaller groups. The temporary settlement had come into being in response to Red Hand’s invitation, taken by his emissaries to the various interested parties. Invitation, not summons.

A high-spirited individual, the Comanche brave was jealous of his freedom and rights. His allegiance was freely given and just as freely withdrawn. Warriors of great deeds were respected, but not slavishly submitted to. A leader gained followers by ability and success; incompetence and failure inevitably incited mass desertions.

It was a mark of Red Hand’s prowess that so many had come to hear his words.

The campsite at Arrowhead Rock lay on a well-watered patch of grassy ground. Cone-shaped tipis massed along the stream banks. Smoke from many cooking fires hazed the area. The tipis had been given over to women and children; the men were elsewhere. Packs of half-wild, half-starved dogs chased each other around the campgrounds, snarling and yapping.

The horse herds were picketed nearby. Comanches reckoned their wealth in horses, as white men did in gold. The greater the thief, the more he was respected and envied by his fellows.

For such a conclave, an informal truce reigned, whereby the braves of various clans held in check their craving to steal each other’s horses ... mostly.

North of the camp, a long bowshot away, the land dipped into a shallow basin, a hollow serving as a kind of natural amphitheater. It was spacious enough to comfortably hold the two hundred and more warriors assembled there under a horned moon. No females were present at the basin.

To a man, they were in prime physical condition. There was no place in the Comanche nation for weaklings. Men were warriors, doing the hunting, raiding, fighting, and killing—sometimes dying. Women did all the other work, the drudgery of the tribe.

The braves were high-spirited, raucous. Much horseplay and boasting of big brags occurred. It had been a long winter; they looked forward to the wild free life of raiding south with eager anticipation. An air of keen interest hung over them as they waited impatiently for Red Hand to take the fore.

At the northern center rim of the basin stood a triangular-shaped rock about twenty feet high. Shaped like an arrowhead planted point-up in the ground, it gave the site its name. Among Comanche warrior society, the arrowhead was an emblem of power and danger, giving the stone an aura of magical potency.

A fire blazed near its base. Yellow-red tongues of flame leaped upward, wreathed with spirals of blue-gray smoke. Between the fire and the rock, a stout wooden stake eight feet tall had been driven into the ground.

The braves faced the rock, Bison Eyes grouped on the left, Dawn Hawks on the right. Both clans were strong, numerous, and well respected. Nearly evenly matched in numbers and fighting prowess, they were great rivals.

A stir went through the crowd. Something was happening.

A handful of shadowy figures stepped out from behind the rock, coming into view of those assembled in the hollow. They ranked themselves in a line behind the fire, forming up like a guard of honor in advance of their leader. Underlit by the flames’ red glare, they could be seen and recognized.

Mighty warriors all, men of renown, they made up Red Hand’s inner circle of trusted advisors and henchmen, his lieutenants.

Ten Scalps was a giant of a man, one of the strongest warriors in the Comanche nation. He’d taken ten scalps as a youth during his first raid. After that he stopped counting.

Sun Dog, his face wider than it was long, had dark eyes glinting like chips of black glass.

Little Bells, with twin strings of tiny silver bells plaited into his lion’s mane of shoulder-length hair, stood tall.

Badger was short and squat, with tremendous upper body strength and oversized, pawlike hands.

Black Robe, clad in a garment he’d stripped from a Mexican priest he’d slain and scalped, was next. Part long coat, part cape, the tattered garment gave him a weird, batlike outline.

The cadre’s appearance was greeted by the crowd with appreciative whoops, shrieks, and howls. The five stood motionless, faces impassive, arms folded across their chests. They held the pose for a long time, their stillness contrasting with the crowd’s mounting excitement.

After a moment, a lone man emerged from behind the rock into the firelight. He wore a war bonnet and carried a lance.

The Bison Eyes clansmen vented loud, full-throated cries of welcome, for the newcomer was none other than their own great man, Red Hand. But Red Hand’s entrance was almost as well received by the rival Dawn Hawks.

He was a man of power, a doer of great deeds. He had stature. He had stolen many horses, enslaved many captives, killed many foes. With skill and daring he had won much fame throughout the plains and deep into Mexico.

Circling around to the front of Arrowhead Rock, Red Hand scrambled up onto a ledge four feet above the ground. Facing the assembled, he showed himself to them. Roughly thirty years of age, he was in full, vigorous prime, broad-shouldered, deep-chested, and long-limbed. Thick coal-black hair, full and unbound, framed a long, sharp-featured face. His eyes were deepset, burning.

He was crowned with a splendid eagle-feather war bonnet whose train reached down his back. He wore a simple breechcloth and knee-length antelope skin boots. A hunting knife hung on his hip.

From fingertips to wrists, the backs of his hands were painted with greasy red coloring, markings that were stripes, wavvy lines, crescent moons, and arrows. His right hand clenched the lance, holding it upright with its base resting atop the rocky ledge. Ten feet long, it was tipped with a wickedly sharp, barbed spear blade.

This was no Comanche war spear. He had taken it in Mexico the summer before from a mounted lancer, one of the legions of crack cavalry troops sent by France’s Emperor Napoleon III to protect his ally Maximilian of Austria-Hungary.

Red Hand knew nothing of the crowned heads of Europe nor of Napoleon III’s mad dream of a New World Empire that had prompted him to install a Hapsburg royal on the throne of Mexico. Red Hand knew killing, though, dodging the lancer’s lunging spear thrust, dragging him down off his fine horse, and cutting his throat.

Word of this enviable weapon spread far and wide among the Comanches. More than a prize, the lance became a talisman of Red Hand’s prestige. It evoked no small interest, with many braves pressing forward, craning for a better look.

Red Hand lifted the weapon, shaking it triumphantly in the air. It was met by a fresh round of appreciative whoops.

Notably lacking in enthusiasm, was Wahtonka, a Dawn Hawks chief standing in the front rank of his clan. He, too, was a great man, with many daring deeds of blood to his credit. But he was fifty years old, a generation older than Red Hand.

Of medium height, Wahtonka was lean and wiry; all bone, sinews, and tendons. His hair, parted in the middle of his scalp, was worn in two long, gray-flecked braids. His face was deeply lined, his mouth downturned, dour.

Red Hand’s enthusiastic audience did nothing to lighten his mood. Others were not so constrained in their appreciation of the upstart, Wahtonka noticed, including many of his own Dawn Hawks. Too many.

The young men were loud in their whooping and hollering, and a number of older, more established warriors also stamped and shouted for Red Hand.

Wahtonka cut a side glance at Laughing Bear standing beside him. Laughing Bear was of his generation, himself a mighty warrior, though with few deeds in recent years to his credit. He was Wahtonka’s kinsman and most trusted ally.

Laughing Bear was heavyset, with sloping shoulders and a blocky torso, thick in the middle. His features were broad and lumpish. The gaze of his small round eyes was bleak. He looked as if he had not laughed in years. Red Hand’s appearance this night had not struck forth in him any spirit of mirth. He shared Wahtonka’s grave concerns about the growing Red Hand problem.

The hero of the hour basked for a moment in the gusty reception given him, before motioning for silence. The Comanches quieted down, though scattered shrieks and screams continued to rise from some of the more excitable types. The clamor subsided, though the crowd kept up a continual buzzing.

“Brothers! I went in search of a vision,” Red Hand began, his voice big and booming. “I went in search of a vision—and I have found it!”

The warriors’ cheers echoed across the nighted prairie.

Red Hand’s face split in a wicked grin, showing strong white teeth. “In the old times life was good. The game was thick. Birds filled the skies. The buffalo were many, covering the ground as far as the eye could see.” He had a far-off look in his eyes, as if gazing through the distance of space and time in search of such onetime abundance.

He frowned, his gaze hardening, dark passions clouding his features. “Then came the white men,” he said, voice thick, almost choking on the words.

The mood of the braves turned. Whoops and screeches faded, replaced by sullen, ominous mutterings accompanied by much solemn nodding of heads in agreement. Red Hand was voicing their universal complaint against the hated invaders who were destroying a cherished way of life.

“First were the Mexicans, with their high-handed ways,” he said, thrusting his lance toward the south, the direction from which the initial trespassers hailed.

“They came in suits of iron, calling themselves ‘conquerers. ’” Red Hand sneered at the conquistadors who had emerged from Mexico some three hundred and fifty years earlier. It might have been yesterday, so fresh and strong was his hate.

“They rode—horses!” Red Hand’s eyes bulged as he assumed an expression of pop-eyed amazement, his clowning provoking shouts and laughter. “We had never seen horses before. The horses were good!”

He paused, then punched the rest of it across. “We killed the men and took their horses! We burned the settlements and killed and killed until only cowards were left alive, and we sent them running back to Mexico!”

The braves spasmed with screaming delight, some shouting themselves hoarse.

Red Hand waited for a lull in the tumult, then continued. “From that day till now, they have never dared return to our hunting grounds. We could have wiped them off the face of the earth, chasing them into the Great Water, had we so desired. Aye, for we Comanche are a mighty folk, and a warlike one. But we were merciful. We took pity on the poor weak creatures and let them live, so they could keep on breeding fine horses for us to steal.

“One black day, out from where the sun rises, came the Texans.”

Texans—the Comanches’ generic term for Anglos, English-speaking whites.

“Texans! They, too, wanted to steal our land and enslave us. They had guns! The guns were good. So we killed the Texans and took their guns and killed more, whipping and burning until they wept like frightened children!

“Not all did we kill, for we Comanches are a merciful people. We let some live so we could take more guns and powder and bullets from them. Their horses are good to steal, too! And their women!

“But the Comanche is too tender hearted for his own good,” he said, shaking his head as if in sorrow. “For a time, all was well. But no more. The Texans forget the lesson we taught them in blood and fire. They come creeping back, pressing at our lands in ever-greater numbers. They will eat up the earth if they are not stopped.

“What to do, brothers, what to do? I prayed to the Great Spirit to send me an answer. And I dreamed a dream. The sky cracked open! The clouds parted, and an arm reached down between them—a mighty red arm, holding a burning spear. The Fire Lance!

“The hand darted the spear. It flew down to earth, striking the ground with a thunderclap. When the smoke cleared, I alone was left standing, for all around me the Texans lay fallen on the ground. Man, woman and child—dead! Dead all, from oldest to youngest, from greatest to most small. All dead. And this was not the least of wonders.

“Everywhere a white person had fallen, a buffalo rose up. Here, there, everywhere a buffalo! They filled the plains with a thundering herd, filling my heart with joy. So it was shown to me in a dream, as I tell it to you. But I tell you this. It was no dream, but a vision!”

Wild stirrings shot through the crowd, a storm of potential energy yearning to be released.

“A true vision!” Red Hand bellowed.

The braves chafed at the bit, straining to break loose, but Red Hand shouted down the rising tumult. “The Great Spirit has shown us the Way—kill the Texans! Take up the Fire Lance! Kill and burn until the last white has fled from these lands, never to be seen again! The buffalo will once more grow thick and fat! All will be well, as in the days of our fathers!”

Brandishing his lance, Red Hand shook it at the heavens. Pandemonium erupted, a near riot. The hollow basin became a howling bedlam as the wild crowd went wilder.

So great was the uproar that, in the tipis, the women and children marveled to hear it. Any outsider, red or white, hearing it crashing across the plains, would have taken fright.

Red Hand hopped down off the ledge that had served him as a platform and stepped back into the shadows, partly withdrawing from the scene while the disturbance played itself out. His henchmen followed.

Presently, order was restored, if not peace and quiet. The braves settled down, in their restless way.

Red Hand put his head together with his five-man cadre, giving orders.

Carrying out his command, Sun Dog and Little Bells moved around to the east side of Arrowhead Rock, where a lone tipi stood off by itself in the gloom beyond the firelight. Sun Dog lifted the front flap and went inside.

A moment later, a figure emerged headfirst through the opening as if violently flung outward, falling facedown in the dirt at Little Bells’s feet.

Sun Dog reappeared. He and Little Bells bracketed a sorry figure, grabbing him by the arms and hauling him to his feet. The newcomer was a white man in cavalry blue. A Long Knife, one of the hated pony soldiers!

There was a collective intake of breath from the mob in the hollow, followed by ominous mutterings and growlings. As one, they pressed forward.

The captive wore a torn blue tunic and pants with a yellow strip down the sides. He was barefoot. His hands were tied in front of him by rawhide strips cutting deep into the flesh of his wrists. He sagged, legs folding at the knees. He would have fallen if Sun Dog and Little Bells hadn’t been holding him up.

He was Butch Hardesty, a robber, rapist, and back-shooting murderer. He had a system. When the law got too hot on his trail, he would enlist in the army and disappear in the ranks, losing himself among blue-clad troopers and distant frontier posts. When the pursuit cooled off, he would steal a horse and rifle and go “over the hill,” deserting to resume his outlaw career. He’d go about his business until the law started dogging him again, once more repeating the cycle.

In the last years of the War Between the States, he worked his way west across the country, finally winding up at lonesome Fort Pardee in north central Texas. He deserted again, and had the extreme bad luck to cross paths with some of Red Hand’s scouts. He’d been doubly unfortunate in being taken alive.

He’d been beaten, starved, abused, and tortured near the extreme. But not all the way to destruction. Red Hand needed him alive. He had a use for him. Hardesty was taken north, to the conclave at Arrowhead Rock. Kept alive and on hand—for what?

Out of the tipi stepped a weird hybrid creature, man-shaped, with a monstrous shaggy horned head.

Coming into the light, the apparition was revealed to be an aged Comanche, pot-bellied and thin-shanked. He wore a brown woolly buffalo hide headdress complete with horns. He was Medicine Hat, Red Hand’s own shaman, herbalist, devil doctor, and sorcerer.

Half carrying and half dragging Hardesty, Sun Dog and Little Bells hustled him to the front of the rock. Medicine Hat shambled after them, mumbling to himself.

The cavalryman produced no small effect on the crowd. Like a magnifying lens focusing the sun’s rays into a single burning beam, the trooper provided a focus for the braves’ bloodlust and demonic energies.

Hardesty was brought to the stake and bound to it. Ropes made of braided buffalo hide strips lashed him to the pole with hands tied above his head. Too weak to stand on his own two feet, the ropes held him up.

When Comanches took an enemy alive, they tortured him, expecting no less should they be taken. Torture was an important element of the warrior society. How a man stood up to it showed what he was made of. It was entertaining, too—to those not on the receiving end.

Hardesty bore the marks of starvation and abuse. His face was mottled with purple-black bruises, features swollen, one blackened eye narrowed to a glinting slit. His mouth hung open. His shirt was ripped open down the middle, his bare torso having been sliced and gouged. Cactus thorns had been driven under his fingernails and toenails. Twigs had been tied between fingers and toes and set aflame. The soles of his feet had been skinned, then roasted.

Firelight caused shadows to crawl and slide across Hardesty’s bound form. He seemed as much dead as alive.

Black Robe now went to work on him with a knife whose blade was heated red-hot. It brought Hardesty around, his bellows of pain booming in the basin.

Badger shot some arrows into Hardesty’s arms and legs, careful to ensure that no wound was mortal.

Each new infliction was greeted with shouts by the braves. It was great sport.

Hardesty was scum and he knew it, but he played his string out to the end. His mouth worked, cursing his captors. “The joke’s on you, ya ignorant savages. I ain’t cavalry a’tall. I’m a deserter. I quit the army, you dumb sons of bitches, haw haw! How d’you like that? Ya heathen devils.”

A few Comanches had a smattering of English, but were unable to make out his words. All liked his show of spirit, however.

“The gods are happiest when the sacrifice is strong,” Red Hand said. “Make ready for the Fire Lance.”

Medicine Hat muttered agreement with a toothless mouth, spittle wetting his pointed chin. Reaching into his bag of tricks, he pulled out a gourd. It was dried and hollowed out, with a long neck serving as a kind of spout. The end of the spout was sealed by a stopper. Pulling the plug, he closed on the captive.

Hardesty slumped against the ropes, head down, and chin resting on top of his chest. He looked up out of the tops of his eyes, his pain-wracked gaze registering little more than a mute flicker of animal awareness.

Red Hand moved forward, out of the shadows into the light. It could be seen that his face was freshly striped with black paint.

War paint! The sight of which sent an electric thrill surging through the throng.

Red Hand motioned Medicine Hat to proceed. The shaman’s moccasined feet shuffled in the dust, doing a little ceremonial dance. Mouthing spells, prayers, and incantations, Medicine Hat neared Hardesty, then backed away, repeating the action several times.

He held the gourd over the captive’s head and. began pouring the vessel’s contents on Hardesty’s head, shoulders, chest, and belly, dousing him with a dark, foul-smelling liquid. Compounded of rendered animal fats, grease, and mineral oils, the stuff was used as a fire starter to quicken the lighting of campfires. It gurgled as it spewed from the spout.

Groans escaped Hardesty as his upper body was coated with the stuff. Medicine Hat poured until the gourd was empty. He stepped away from Hardesty, who looked as if he’d been drenched with glistening brown oil.

Red Hand moved forward, the center of all eyes.

The shaman was a great one for brewing up various potions, powders, and salves. Earlier, he had applied a special ointment to the spear blade of Red Hat’s lance. The main ingredient of the mixture was a thick, sticky pine tar resin blended with vegetable and herbal oils. It coated the blade, showing as a gummy residue that dulled the brilliance of the steel’s metallic shine.

Red Hand’s movements took on a deliberate, ritualistic quality. Holding the lance in both hands, he raised it horizontally over his head and shook it at the heavens. Lowering it, he dipped the blade into the heart of the fire. A few beats passed before the slow-burning ointment flared up, wrapping the blade in blue flames.

Red Hand lifted the lance, tilting it skyward for all to see. The blade was a wedge of blue fire, burning with an eerie, mystic glow—a ghost light, a weird effect both impressive and unnerving.

Quivering with emotion, Red Hand’s clear, strong voice rang out. “Lo! The Fire Lance!”

He touched the burning spear to Hardesty’s well-oiled chest. Blue fire sparked from the blade tip, leaping to the oily substance coating the captive’s flesh. The fire-starting compound burst into bright hot flames, wrapping Hardesty in a skin of fire, turning him into a human torch.

He blazed with a hot yellow-red-orange light. The burning had a crackling sound, like flags being whipped by a high wind.

Hardesty writhed, screaming as he was burned alive. Fire cut through the ropes binding him to the stake. Before he could break free, he was speared by Red Hand, who skewered him in the middle.

Red Hand opened up Hardesty’s belly, spilling his guts. He gave a final twist to the blade before withdrawing it. He faced the man of fire, lance leveled for another thrust if needed.

Hardesty collapsed, falling in a blazing heap. The fire spread to some nearby grass and brush, setting them alight.

At a sign from Red Hand, members of his five-man cadre rushed up with blankets, using them to beat out the fires. Streamers of blue-gray smoke rose up. The night was thick with the smell of burning flesh.

Red Hand thrust the blue-burning spear blade into a dirt mound. When it was surfaced, the mystic glow was extinguished, the blade glowing a dull red.

Chaos, near anarchy, reigned among the Comanches. The horde erupted in a frenzy, many breaking into spontaneous war dances.

Above all others was heard the voice of Red Hand. “Take up the Fire Lance! Kill the Texans!”

Much later, when all was quiet, Wahtonka and Laughing Bear stood off by themselves in a secluded place, putting their heads together. The horned moon was low in the west, the stars were paling, the eastern sky was lightening.

“What should we do?” Laughing Bear asked.

“What can we do? Go with Red Hand to make war on the whites.” Wahtonka shrugged. “Any raid is better than none,” he added, philosophically.

Laughing Bear grunted agreement. “Waugh! That is true.”

“We shall see if the Great Spirit truly spoke to Red Hand, if his vision comes to pass,” Wahtonka said. “If not—may his bones bleach in the sand!”

The town of Hangtree, county seat of Hangtree County, Texas, was known to most folks, except for a few town boosters and straitlaced respectable types, as Hangtown. So it was to Johnny Cross, a native son of the region.

Located in north central Texas, Hangtree County lay west of Palo Pinto County and east of the Llano Estacado, known as the Staked Plains, whose vast emptiness was bare of towns or settlements for hundreds of square miles. Hangtown squatted on the lip of that unbounded immensity.

The old Cross ranch lay some miles west of town, nestled at the foot of the eastern range of the Broken Hills, called the Breaks. Beyond the Breaks lay the beginnings of the Staked Plains.

Johnny, the last living member of the Cross family, had come back to Hangtree after the war. He lived at the ranch with his old buddy Luke Pettigrew, two not-so-ex-Rebels trying to make a go of it in the hard times of the year following the fall of the Confederacy. They were partners in a mustang venture. Hundreds of mustangs ran wild and free in the Breaks and Johnny and Luke sold whatever they could catch.

Growing up in Hangtree, Johnny and Luke were boyhood pals. When war came in 1861, both were quick to fight for the South, like most of the menfolk in the Lone Star state. Luke joined up with Hood’s Texans, a hard-fighting outfit that had made its mark in most of the big battles of the war. In the last year of the conflict, a Yankee cannonball had taken off his left leg below the knee. A wooden leg took its place.

Johnny Cross had followed a different path. For good or ill, his star had led him to throw in with Quantrill’s Raiders, legendary in its own way, though not with the bright, untarnished glory of Hood’s fighting force. Johnny spent the next four years serving with that dark command, living mostly on horseback, fighting his way through the bloody guerrilla warfare of the border states.

A dead shot when he first joined Quantrill, he soon became a formidable pistol fighter and long rider, a cool-nerved killing machine. His comrades in arms included the likes of Bloody Bill Anderson, the Younger brothers, and Frank and Jesse James.

The bushwhackers’ war in Kansas and Missouri was a murky, dirty business where the lines blurred between soldier and civilian, valor and savagery, and it was easy to lose one’s way.

When Richmond fell and Dixie folded in ’65, Quantrill and his men received no amnesty. They were wanted outlaws with a price on their h. . .

Six hundred and more Comanche men, women, and children were camped near a stream in a valley north of the Texas panhandle, on land between the Canadian and Arkansas rivers. The site, Arrowhead Rock, lay deep in the heart of the vast, untamed territory of Comancheria, home grounds of the tribal nation.

The gathering was made up mostly of two main subgroups, the Bison Eyes and the Dawn Hawks, along with a number of lesser clans, relations, and allies.

Red Hand, a Bison Eye, was a rising star who had led a number of successful raids in recent seasons past. Many braves, especially those of the younger generation, were eager to attach themselves to him.

Others had come to hear him out and make up their own minds about whether or not to follow his lead. Not a few had come to keep a wary eye on him and see what he was up to.

All brought their families with them, from the oldest squaws to the youngest babes in arms. They brought their tipis and personal belongings, horse herds, and even dogs.

The Comanche were a mobile folk, nomads who followed the buffalo herds across the Great Plains. They spent much of their lives on horseback and were superb riders. They were fierce fighters, arguably the most dangerous Indian tribe in the West. They gloried in the title of Lords of the Southern Plains.

Farther southwest—much farther—lay the lands of the Apache, relentless desert warriors of fearsome repute. During their seasonal wanderings Comanches raided Apaches as the opportunity presented itself, but the Apache did not strike north to raid Comancheria. This stark fact spoke volumes about the relative deadliness of the two.

The camp on the valley stream was unusual in its size, the tribesmen generally preferring to travel in much smaller groups. The temporary settlement had come into being in response to Red Hand’s invitation, taken by his emissaries to the various interested parties. Invitation, not summons.

A high-spirited individual, the Comanche brave was jealous of his freedom and rights. His allegiance was freely given and just as freely withdrawn. Warriors of great deeds were respected, but not slavishly submitted to. A leader gained followers by ability and success; incompetence and failure inevitably incited mass desertions.

It was a mark of Red Hand’s prowess that so many had come to hear his words.

The campsite at Arrowhead Rock lay on a well-watered patch of grassy ground. Cone-shaped tipis massed along the stream banks. Smoke from many cooking fires hazed the area. The tipis had been given over to women and children; the men were elsewhere. Packs of half-wild, half-starved dogs chased each other around the campgrounds, snarling and yapping.

The horse herds were picketed nearby. Comanches reckoned their wealth in horses, as white men did in gold. The greater the thief, the more he was respected and envied by his fellows.

For such a conclave, an informal truce reigned, whereby the braves of various clans held in check their craving to steal each other’s horses ... mostly.

North of the camp, a long bowshot away, the land dipped into a shallow basin, a hollow serving as a kind of natural amphitheater. It was spacious enough to comfortably hold the two hundred and more warriors assembled there under a horned moon. No females were present at the basin.

To a man, they were in prime physical condition. There was no place in the Comanche nation for weaklings. Men were warriors, doing the hunting, raiding, fighting, and killing—sometimes dying. Women did all the other work, the drudgery of the tribe.

The braves were high-spirited, raucous. Much horseplay and boasting of big brags occurred. It had been a long winter; they looked forward to the wild free life of raiding south with eager anticipation. An air of keen interest hung over them as they waited impatiently for Red Hand to take the fore.

At the northern center rim of the basin stood a triangular-shaped rock about twenty feet high. Shaped like an arrowhead planted point-up in the ground, it gave the site its name. Among Comanche warrior society, the arrowhead was an emblem of power and danger, giving the stone an aura of magical potency.

A fire blazed near its base. Yellow-red tongues of flame leaped upward, wreathed with spirals of blue-gray smoke. Between the fire and the rock, a stout wooden stake eight feet tall had been driven into the ground.

The braves faced the rock, Bison Eyes grouped on the left, Dawn Hawks on the right. Both clans were strong, numerous, and well respected. Nearly evenly matched in numbers and fighting prowess, they were great rivals.

A stir went through the crowd. Something was happening.

A handful of shadowy figures stepped out from behind the rock, coming into view of those assembled in the hollow. They ranked themselves in a line behind the fire, forming up like a guard of honor in advance of their leader. Underlit by the flames’ red glare, they could be seen and recognized.

Mighty warriors all, men of renown, they made up Red Hand’s inner circle of trusted advisors and henchmen, his lieutenants.

Ten Scalps was a giant of a man, one of the strongest warriors in the Comanche nation. He’d taken ten scalps as a youth during his first raid. After that he stopped counting.

Sun Dog, his face wider than it was long, had dark eyes glinting like chips of black glass.

Little Bells, with twin strings of tiny silver bells plaited into his lion’s mane of shoulder-length hair, stood tall.

Badger was short and squat, with tremendous upper body strength and oversized, pawlike hands.

Black Robe, clad in a garment he’d stripped from a Mexican priest he’d slain and scalped, was next. Part long coat, part cape, the tattered garment gave him a weird, batlike outline.

The cadre’s appearance was greeted by the crowd with appreciative whoops, shrieks, and howls. The five stood motionless, faces impassive, arms folded across their chests. They held the pose for a long time, their stillness contrasting with the crowd’s mounting excitement.

After a moment, a lone man emerged from behind the rock into the firelight. He wore a war bonnet and carried a lance.

The Bison Eyes clansmen vented loud, full-throated cries of welcome, for the newcomer was none other than their own great man, Red Hand. But Red Hand’s entrance was almost as well received by the rival Dawn Hawks.

He was a man of power, a doer of great deeds. He had stature. He had stolen many horses, enslaved many captives, killed many foes. With skill and daring he had won much fame throughout the plains and deep into Mexico.

Circling around to the front of Arrowhead Rock, Red Hand scrambled up onto a ledge four feet above the ground. Facing the assembled, he showed himself to them. Roughly thirty years of age, he was in full, vigorous prime, broad-shouldered, deep-chested, and long-limbed. Thick coal-black hair, full and unbound, framed a long, sharp-featured face. His eyes were deepset, burning.

He was crowned with a splendid eagle-feather war bonnet whose train reached down his back. He wore a simple breechcloth and knee-length antelope skin boots. A hunting knife hung on his hip.

From fingertips to wrists, the backs of his hands were painted with greasy red coloring, markings that were stripes, wavvy lines, crescent moons, and arrows. His right hand clenched the lance, holding it upright with its base resting atop the rocky ledge. Ten feet long, it was tipped with a wickedly sharp, barbed spear blade.

This was no Comanche war spear. He had taken it in Mexico the summer before from a mounted lancer, one of the legions of crack cavalry troops sent by France’s Emperor Napoleon III to protect his ally Maximilian of Austria-Hungary.

Red Hand knew nothing of the crowned heads of Europe nor of Napoleon III’s mad dream of a New World Empire that had prompted him to install a Hapsburg royal on the throne of Mexico. Red Hand knew killing, though, dodging the lancer’s lunging spear thrust, dragging him down off his fine horse, and cutting his throat.

Word of this enviable weapon spread far and wide among the Comanches. More than a prize, the lance became a talisman of Red Hand’s prestige. It evoked no small interest, with many braves pressing forward, craning for a better look.

Red Hand lifted the weapon, shaking it triumphantly in the air. It was met by a fresh round of appreciative whoops.

Notably lacking in enthusiasm, was Wahtonka, a Dawn Hawks chief standing in the front rank of his clan. He, too, was a great man, with many daring deeds of blood to his credit. But he was fifty years old, a generation older than Red Hand.

Of medium height, Wahtonka was lean and wiry; all bone, sinews, and tendons. His hair, parted in the middle of his scalp, was worn in two long, gray-flecked braids. His face was deeply lined, his mouth downturned, dour.

Red Hand’s enthusiastic audience did nothing to lighten his mood. Others were not so constrained in their appreciation of the upstart, Wahtonka noticed, including many of his own Dawn Hawks. Too many.

The young men were loud in their whooping and hollering, and a number of older, more established warriors also stamped and shouted for Red Hand.

Wahtonka cut a side glance at Laughing Bear standing beside him. Laughing Bear was of his generation, himself a mighty warrior, though with few deeds in recent years to his credit. He was Wahtonka’s kinsman and most trusted ally.

Laughing Bear was heavyset, with sloping shoulders and a blocky torso, thick in the middle. His features were broad and lumpish. The gaze of his small round eyes was bleak. He looked as if he had not laughed in years. Red Hand’s appearance this night had not struck forth in him any spirit of mirth. He shared Wahtonka’s grave concerns about the growing Red Hand problem.

The hero of the hour basked for a moment in the gusty reception given him, before motioning for silence. The Comanches quieted down, though scattered shrieks and screams continued to rise from some of the more excitable types. The clamor subsided, though the crowd kept up a continual buzzing.

“Brothers! I went in search of a vision,” Red Hand began, his voice big and booming. “I went in search of a vision—and I have found it!”

The warriors’ cheers echoed across the nighted prairie.

Red Hand’s face split in a wicked grin, showing strong white teeth. “In the old times life was good. The game was thick. Birds filled the skies. The buffalo were many, covering the ground as far as the eye could see.” He had a far-off look in his eyes, as if gazing through the distance of space and time in search of such onetime abundance.

He frowned, his gaze hardening, dark passions clouding his features. “Then came the white men,” he said, voice thick, almost choking on the words.

The mood of the braves turned. Whoops and screeches faded, replaced by sullen, ominous mutterings accompanied by much solemn nodding of heads in agreement. Red Hand was voicing their universal complaint against the hated invaders who were destroying a cherished way of life.

“First were the Mexicans, with their high-handed ways,” he said, thrusting his lance toward the south, the direction from which the initial trespassers hailed.

“They came in suits of iron, calling themselves ‘conquerers. ’” Red Hand sneered at the conquistadors who had emerged from Mexico some three hundred and fifty years earlier. It might have been yesterday, so fresh and strong was his hate.

“They rode—horses!” Red Hand’s eyes bulged as he assumed an expression of pop-eyed amazement, his clowning provoking shouts and laughter. “We had never seen horses before. The horses were good!”

He paused, then punched the rest of it across. “We killed the men and took their horses! We burned the settlements and killed and killed until only cowards were left alive, and we sent them running back to Mexico!”

The braves spasmed with screaming delight, some shouting themselves hoarse.

Red Hand waited for a lull in the tumult, then continued. “From that day till now, they have never dared return to our hunting grounds. We could have wiped them off the face of the earth, chasing them into the Great Water, had we so desired. Aye, for we Comanche are a mighty folk, and a warlike one. But we were merciful. We took pity on the poor weak creatures and let them live, so they could keep on breeding fine horses for us to steal.

“One black day, out from where the sun rises, came the Texans.”

Texans—the Comanches’ generic term for Anglos, English-speaking whites.

“Texans! They, too, wanted to steal our land and enslave us. They had guns! The guns were good. So we killed the Texans and took their guns and killed more, whipping and burning until they wept like frightened children!

“Not all did we kill, for we Comanches are a merciful people. We let some live so we could take more guns and powder and bullets from them. Their horses are good to steal, too! And their women!

“But the Comanche is too tender hearted for his own good,” he said, shaking his head as if in sorrow. “For a time, all was well. But no more. The Texans forget the lesson we taught them in blood and fire. They come creeping back, pressing at our lands in ever-greater numbers. They will eat up the earth if they are not stopped.

“What to do, brothers, what to do? I prayed to the Great Spirit to send me an answer. And I dreamed a dream. The sky cracked open! The clouds parted, and an arm reached down between them—a mighty red arm, holding a burning spear. The Fire Lance!

“The hand darted the spear. It flew down to earth, striking the ground with a thunderclap. When the smoke cleared, I alone was left standing, for all around me the Texans lay fallen on the ground. Man, woman and child—dead! Dead all, from oldest to youngest, from greatest to most small. All dead. And this was not the least of wonders.

“Everywhere a white person had fallen, a buffalo rose up. Here, there, everywhere a buffalo! They filled the plains with a thundering herd, filling my heart with joy. So it was shown to me in a dream, as I tell it to you. But I tell you this. It was no dream, but a vision!”

Wild stirrings shot through the crowd, a storm of potential energy yearning to be released.

“A true vision!” Red Hand bellowed.

The braves chafed at the bit, straining to break loose, but Red Hand shouted down the rising tumult. “The Great Spirit has shown us the Way—kill the Texans! Take up the Fire Lance! Kill and burn until the last white has fled from these lands, never to be seen again! The buffalo will once more grow thick and fat! All will be well, as in the days of our fathers!”

Brandishing his lance, Red Hand shook it at the heavens. Pandemonium erupted, a near riot. The hollow basin became a howling bedlam as the wild crowd went wilder.

So great was the uproar that, in the tipis, the women and children marveled to hear it. Any outsider, red or white, hearing it crashing across the plains, would have taken fright.

Red Hand hopped down off the ledge that had served him as a platform and stepped back into the shadows, partly withdrawing from the scene while the disturbance played itself out. His henchmen followed.

Presently, order was restored, if not peace and quiet. The braves settled down, in their restless way.

Red Hand put his head together with his five-man cadre, giving orders.

Carrying out his command, Sun Dog and Little Bells moved around to the east side of Arrowhead Rock, where a lone tipi stood off by itself in the gloom beyond the firelight. Sun Dog lifted the front flap and went inside.

A moment later, a figure emerged headfirst through the opening as if violently flung outward, falling facedown in the dirt at Little Bells’s feet.

Sun Dog reappeared. He and Little Bells bracketed a sorry figure, grabbing him by the arms and hauling him to his feet. The newcomer was a white man in cavalry blue. A Long Knife, one of the hated pony soldiers!

There was a collective intake of breath from the mob in the hollow, followed by ominous mutterings and growlings. As one, they pressed forward.

The captive wore a torn blue tunic and pants with a yellow strip down the sides. He was barefoot. His hands were tied in front of him by rawhide strips cutting deep into the flesh of his wrists. He sagged, legs folding at the knees. He would have fallen if Sun Dog and Little Bells hadn’t been holding him up.

He was Butch Hardesty, a robber, rapist, and back-shooting murderer. He had a system. When the law got too hot on his trail, he would enlist in the army and disappear in the ranks, losing himself among blue-clad troopers and distant frontier posts. When the pursuit cooled off, he would steal a horse and rifle and go “over the hill,” deserting to resume his outlaw career. He’d go about his business until the law started dogging him again, once more repeating the cycle.

In the last years of the War Between the States, he worked his way west across the country, finally winding up at lonesome Fort Pardee in north central Texas. He deserted again, and had the extreme bad luck to cross paths with some of Red Hand’s scouts. He’d been doubly unfortunate in being taken alive.

He’d been beaten, starved, abused, and tortured near the extreme. But not all the way to destruction. Red Hand needed him alive. He had a use for him. Hardesty was taken north, to the conclave at Arrowhead Rock. Kept alive and on hand—for what?

Out of the tipi stepped a weird hybrid creature, man-shaped, with a monstrous shaggy horned head.

Coming into the light, the apparition was revealed to be an aged Comanche, pot-bellied and thin-shanked. He wore a brown woolly buffalo hide headdress complete with horns. He was Medicine Hat, Red Hand’s own shaman, herbalist, devil doctor, and sorcerer.

Half carrying and half dragging Hardesty, Sun Dog and Little Bells hustled him to the front of the rock. Medicine Hat shambled after them, mumbling to himself.

The cavalryman produced no small effect on the crowd. Like a magnifying lens focusing the sun’s rays into a single burning beam, the trooper provided a focus for the braves’ bloodlust and demonic energies.

Hardesty was brought to the stake and bound to it. Ropes made of braided buffalo hide strips lashed him to the pole with hands tied above his head. Too weak to stand on his own two feet, the ropes held him up.

When Comanches took an enemy alive, they tortured him, expecting no less should they be taken. Torture was an important element of the warrior society. How a man stood up to it showed what he was made of. It was entertaining, too—to those not on the receiving end.

Hardesty bore the marks of starvation and abuse. His face was mottled with purple-black bruises, features swollen, one blackened eye narrowed to a glinting slit. His mouth hung open. His shirt was ripped open down the middle, his bare torso having been sliced and gouged. Cactus thorns had been driven under his fingernails and toenails. Twigs had been tied between fingers and toes and set aflame. The soles of his feet had been skinned, then roasted.

Firelight caused shadows to crawl and slide across Hardesty’s bound form. He seemed as much dead as alive.

Black Robe now went to work on him with a knife whose blade was heated red-hot. It brought Hardesty around, his bellows of pain booming in the basin.

Badger shot some arrows into Hardesty’s arms and legs, careful to ensure that no wound was mortal.

Each new infliction was greeted with shouts by the braves. It was great sport.

Hardesty was scum and he knew it, but he played his string out to the end. His mouth worked, cursing his captors. “The joke’s on you, ya ignorant savages. I ain’t cavalry a’tall. I’m a deserter. I quit the army, you dumb sons of bitches, haw haw! How d’you like that? Ya heathen devils.”

A few Comanches had a smattering of English, but were unable to make out his words. All liked his show of spirit, however.

“The gods are happiest when the sacrifice is strong,” Red Hand said. “Make ready for the Fire Lance.”

Medicine Hat muttered agreement with a toothless mouth, spittle wetting his pointed chin. Reaching into his bag of tricks, he pulled out a gourd. It was dried and hollowed out, with a long neck serving as a kind of spout. The end of the spout was sealed by a stopper. Pulling the plug, he closed on the captive.

Hardesty slumped against the ropes, head down, and chin resting on top of his chest. He looked up out of the tops of his eyes, his pain-wracked gaze registering little more than a mute flicker of animal awareness.

Red Hand moved forward, out of the shadows into the light. It could be seen that his face was freshly striped with black paint.

War paint! The sight of which sent an electric thrill surging through the throng.

Red Hand motioned Medicine Hat to proceed. The shaman’s moccasined feet shuffled in the dust, doing a little ceremonial dance. Mouthing spells, prayers, and incantations, Medicine Hat neared Hardesty, then backed away, repeating the action several times.

He held the gourd over the captive’s head and. began pouring the vessel’s contents on Hardesty’s head, shoulders, chest, and belly, dousing him with a dark, foul-smelling liquid. Compounded of rendered animal fats, grease, and mineral oils, the stuff was used as a fire starter to quicken the lighting of campfires. It gurgled as it spewed from the spout.

Groans escaped Hardesty as his upper body was coated with the stuff. Medicine Hat poured until the gourd was empty. He stepped away from Hardesty, who looked as if he’d been drenched with glistening brown oil.

Red Hand moved forward, the center of all eyes.

The shaman was a great one for brewing up various potions, powders, and salves. Earlier, he had applied a special ointment to the spear blade of Red Hat’s lance. The main ingredient of the mixture was a thick, sticky pine tar resin blended with vegetable and herbal oils. It coated the blade, showing as a gummy residue that dulled the brilliance of the steel’s metallic shine.

Red Hand’s movements took on a deliberate, ritualistic quality. Holding the lance in both hands, he raised it horizontally over his head and shook it at the heavens. Lowering it, he dipped the blade into the heart of the fire. A few beats passed before the slow-burning ointment flared up, wrapping the blade in blue flames.

Red Hand lifted the lance, tilting it skyward for all to see. The blade was a wedge of blue fire, burning with an eerie, mystic glow—a ghost light, a weird effect both impressive and unnerving.

Quivering with emotion, Red Hand’s clear, strong voice rang out. “Lo! The Fire Lance!”

He touched the burning spear to Hardesty’s well-oiled chest. Blue fire sparked from the blade tip, leaping to the oily substance coating the captive’s flesh. The fire-starting compound burst into bright hot flames, wrapping Hardesty in a skin of fire, turning him into a human torch.

He blazed with a hot yellow-red-orange light. The burning had a crackling sound, like flags being whipped by a high wind.

Hardesty writhed, screaming as he was burned alive. Fire cut through the ropes binding him to the stake. Before he could break free, he was speared by Red Hand, who skewered him in the middle.

Red Hand opened up Hardesty’s belly, spilling his guts. He gave a final twist to the blade before withdrawing it. He faced the man of fire, lance leveled for another thrust if needed.

Hardesty collapsed, falling in a blazing heap. The fire spread to some nearby grass and brush, setting them alight.

At a sign from Red Hand, members of his five-man cadre rushed up with blankets, using them to beat out the fires. Streamers of blue-gray smoke rose up. The night was thick with the smell of burning flesh.

Red Hand thrust the blue-burning spear blade into a dirt mound. When it was surfaced, the mystic glow was extinguished, the blade glowing a dull red.

Chaos, near anarchy, reigned among the Comanches. The horde erupted in a frenzy, many breaking into spontaneous war dances.

Above all others was heard the voice of Red Hand. “Take up the Fire Lance! Kill the Texans!”

Much later, when all was quiet, Wahtonka and Laughing Bear stood off by themselves in a secluded place, putting their heads together. The horned moon was low in the west, the stars were paling, the eastern sky was lightening.

“What should we do?” Laughing Bear asked.

“What can we do? Go with Red Hand to make war on the whites.” Wahtonka shrugged. “Any raid is better than none,” he added, philosophically.

Laughing Bear grunted agreement. “Waugh! That is true.”

“We shall see if the Great Spirit truly spoke to Red Hand, if his vision comes to pass,” Wahtonka said. “If not—may his bones bleach in the sand!”

The town of Hangtree, county seat of Hangtree County, Texas, was known to most folks, except for a few town boosters and straitlaced respectable types, as Hangtown. So it was to Johnny Cross, a native son of the region.

Located in north central Texas, Hangtree County lay west of Palo Pinto County and east of the Llano Estacado, known as the Staked Plains, whose vast emptiness was bare of towns or settlements for hundreds of square miles. Hangtown squatted on the lip of that unbounded immensity.

The old Cross ranch lay some miles west of town, nestled at the foot of the eastern range of the Broken Hills, called the Breaks. Beyond the Breaks lay the beginnings of the Staked Plains.

Johnny, the last living member of the Cross family, had come back to Hangtree after the war. He lived at the ranch with his old buddy Luke Pettigrew, two not-so-ex-Rebels trying to make a go of it in the hard times of the year following the fall of the Confederacy. They were partners in a mustang venture. Hundreds of mustangs ran wild and free in the Breaks and Johnny and Luke sold whatever they could catch.

Growing up in Hangtree, Johnny and Luke were boyhood pals. When war came in 1861, both were quick to fight for the South, like most of the menfolk in the Lone Star state. Luke joined up with Hood’s Texans, a hard-fighting outfit that had made its mark in most of the big battles of the war. In the last year of the conflict, a Yankee cannonball had taken off his left leg below the knee. A wooden leg took its place.

Johnny Cross had followed a different path. For good or ill, his star had led him to throw in with Quantrill’s Raiders, legendary in its own way, though not with the bright, untarnished glory of Hood’s fighting force. Johnny spent the next four years serving with that dark command, living mostly on horseback, fighting his way through the bloody guerrilla warfare of the border states.

A dead shot when he first joined Quantrill, he soon became a formidable pistol fighter and long rider, a cool-nerved killing machine. His comrades in arms included the likes of Bloody Bill Anderson, the Younger brothers, and Frank and Jesse James.

The bushwhackers’ war in Kansas and Missouri was a murky, dirty business where the lines blurred between soldier and civilian, valor and savagery, and it was easy to lose one’s way.

When Richmond fell and Dixie folded in ’65, Quantrill and his men received no amnesty. They were wanted outlaws with a price on their h. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

A Good Day to Die

William W. Johnstone

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved