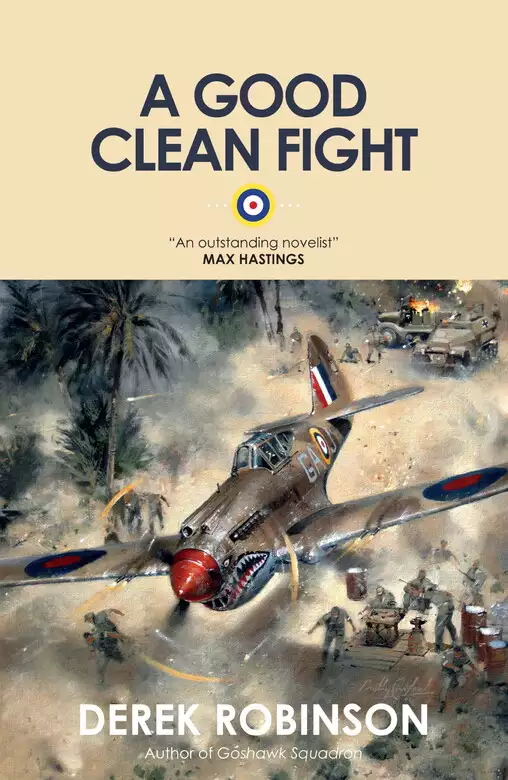

A Good Clean Fight

- eBook

- Paperback

- Audiobook

- Hardcover

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

North Africa, 1942. Dust, heat, thirst, flies. For those who liked that sort of thing, it was a good clean fight: nothing to harm but the sand, the enemy and yourself. Striking hard and escaping fast, Fanny Barton’s squadron play Russian roulette, flying their clapped out Tomahawks on ground-strafing forays. On the ground, the men of Captain Lampard’s SAS patrol drive hundreds of miles behind enemy lines to plant bombs on German aircraft. This is the story of the desert war waged by the men of the RAF and SAS versus the Luftwaffe and the Afrika Korps – a war of no glamour and few heroes in a setting often more lethal than the enemy.

Release date: October 1, 2011

Publisher: MacLehose Press

Print pages: 577

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

A Good Clean Fight

Derek Robinson

Barce was in Libya, near enough to the comforts of Benghazi and far enough from the Gazala Line, which was a couple of hundred miles to the east, near Tobruk. Beyond the Gazala Line (which existed on the map, but was mainly minefields, and so invisible) were the enemy: British, Australians, New Zealanders, Rhodesians, South Africans, Indians. So you were usually safe enough at Barce. If you were a Me l09 pilot you flew every day – training exercises, mock combat, gunnery practice – just to keep yourself tuned-up. When you landed you could go for a swim in the Med, maybe drive into Benghazi for a meal. It was a good life. Rewarding by day and relaxing by night. It would come to an end soon. One more big shove by the Afrika Korps and Rommel would be in Alexandria. Where would the British go then? India, probably. That was somewhat beyond the range of a 109, even with drop-tanks.

The only thing conceivably wrong with Barce (and the half-dozen other airfields along the coastal strip between Benghazi and Tobruk) was a range of mountains just to the south, called the Jebel al Akhdar; and even the Jebel wasn’t much of a problem because as mountains go they were more like high hills: in fact they had to work hard to reach a couple of thousand feet. Nevertheless, if the weather suddenly closed in – and it could rain like a bastard in this part of Africa – then a bit of careless navigation could lead you to try to fly slap through the limestone escarpment of the Jebel. So far nobody had succeeded in achieving this feat, although a couple of scorched wrecks marked the sites of brave attempts.

* * *

Captain Lampard and Sergeant Davis came across one of the wrecks just below the rim of the escarpment and sat in the shade of what was left of a wing while they looked down on Barce. It was midday and the heat was brutal. Lampard had chosen to leave their camp, hidden five miles back in the Jebel, and come here at midday because he reckoned nobody down there would be looking up. And even if someone did look up, all he would see would be dazzle and shimmer and, if his eyesight was phenomenally good, the army of flies that followed Lampard and Davis everywhere. If they followed Lampard rather more faithfully it was not because he was the officer but because he was six foot two and there was more of him to overheat.

Each man examined the airfield through binoculars while the flies walked around their ears, lips and nostrils.

“See the wire?” Lampard said.

“Yes. Concertina, the usual stuff.” Davis spat out a reckless fly. “We can cut it, easy.”

“Might be an alarm wire running through the middle. Cut that and bells start ringing.”

“Doubt it,” Davis said. “Look at the length of the perimeter. Bloody miles. Think of the current you’d need.”

Lampard thought about it while he went on looking, and then said: “Doesn’t matter, anyway. There’s a damn great gap. See? Far right.”

Davis found the gap in the wire. It was where the coastal road passed closest to the airfield. As they watched, a truck swung off the road and drove through the gap. “That’s daft,” he said. “Why string up miles of wire if you’re going to leave a hole? I can’t believe it.”

“Maybe they shut it up at night,” Lampard suggested.

“Can’t see any spare wire lying around. No sentry, either. That’s sloppy, that is. Not like Jerry at all.” Davis was a Guardsman; he disapproved of sloppiness, even German sloppiness.

But Lampard had already lost interest in the unfinished wire. He had turned his binoculars on the built-up area of the airfield and he was watching the arrival of a large staff car, an Alfa-Romeo with the top down. Three officers and a dog got out. The dog was enormous, as big as a young pony. It cantered around the car, skidded to a halt in front of one of the officers, reared up, put its paws on his shoulders and licked his face. He stumbled backwards and the dog fell off him. Lampard saw the silent laughter of the other men. One of them clapped his hands, soundlessly. The dog bounded amongst them and the man whose face it had licked shook his fist, then took a little run, swung his leg and kicked it on the rump. “Did you see that, Davis?” Lampard gazed wide-eyed at the sergeant. “First they invade Poland, then they go around kicking dogs. People like that have got to be taught a lesson.”

Lampard booted the blistered wreckage of the German aeroplane, hard, as they went back up the escarpment. “That’s blindingly obvious,” he said.

“I wonder how much one of these costs, new,” Davis said.

“Ten thousand pounds, I think. Twenty, by the time they’ve got it all the way out here.”

“So there must be about half a million quid standing around down there.” Davis paused to take a last, backward look. “I hope they got good insurance.” Lampard was already at the top, striding hard, rapidly moving out of sight. Lampard knew only two speeds: asleep, and apace.

* * *

They came back at ten o’clock that night with three more men: a lieutenant called Dunn and two corporals, Pocock and Harris. Apart from desert boots and black stocking-caps, they wore normal British army battledress, so dirty that it was more charcoal-grey than khaki. They were all bearded and their faces were sunburned to a deep teak that merged with the night. Each man carried a rucksack, a revolver and six grenades. Lampard also had a tommy-gun. There was no moon. From the top of the escarpment, Barce airfield was a total blank. Even the road that ran past it was lost in the darkness.

Lampard could find only one track down the escarpment so he led his party down it. The track wandered aimlessly and took them into clumps of scrub or across patches of scree. The scrub grabbed at their arms and tugged at the rucksacks. The scree collapsed beneath their feet and sent them slithering, hands raked by the broken stones. Before they were halfway down it was obvious that the track had lost them, or they had lost it, or maybe it had never meant to go all the way to the bottom anyway. Lampard waited while they gathered round him. The starlight was just bright enough to let him count them. “Any damage?” he said. Everyone was scratched and bleeding, but Lampard meant something serious, a broken leg or, even worse, a lost rucksack. Nobody spoke.

He followed the contours until he met a dry streambed. At least that’s what it looked like; it was certainly a gully that seemed to take the shortest route down the hillside. He stepped into it and dislodged a rock that made off at great speed, leaving small, rattling avalanches behind it.

“One at a time down here,” Lampard said. “Allow a decent interval. No point in stopping a rock with your head. This is liable to be a bit steep.”

He went first. It was more than a bit steep. By sliding on his hands and backside and braking with his boots he made fast, painful progress. Pebbles scuttled alongside him. Then it got steeper and the pebbles were beating him. He glimpsed a looming boulder blocking the streambed, got his feet up in time and flexed his legs; even so, the shock jarred all his joints and left him sprawled over the boulder with the gun-muzzle poking his ear and the grenades making dents in his chest.

When his breath came back he stood on the boulder. It looked very black on the other side. He tossed a stone and it told him his future: the gully dropped thirty feet straight down. Maybe more.

The others arrived at safe intervals. He led them round the boulder and tried to get back into the streambed lower down but, perversely, there was no streambed. Evidently the water went underground. There was, however, a new track. It wandered, but it always wandered downwards. In five minutes they were on the plain. Fifteen minutes later they reached the road and they were looking at the gap in the wire and at notice boards stuck in the ground at each end of the gap. The notices said Achtung! Minen. They also carried a skull and crossbones. “That’s all balls,” Lampard said softly.

They eased their rucksack straps and waited. The starlight was slightly brighter now, and the notice boards, stencilled black on white, were big and obvious.

“Well, you’re the boss,” Lieutenant Dunn said. They were grouped closely together.

“Hang on,” Davis said. “Let’s think about this.”

“It’s all balls,” Lampard said. “Put up to scare off the Arabs.”

“I don’t remember seeing them this afternoon,” Davis said. “In fact I’m sure I didn’t.”

Dunn said: “You don’t think they might have mined the gap this evening, Jack?”

“Not a chance. Jerry transport uses it as a short-cut to get on and off the airfield. We saw them do it.”

Corporal Pocock, who had gone forward, came back and said: “You can see the tyre tracks, sir. And plenty of footprints too. No sign of mines.”

“What sort of sign did you expect to see?” Davis asked.

“Dunno. Disturbed earth, that sort of thing.”

“The entire bloody gap is disturbed earth.”

“Listen,” Lampard said, “they haven’t mined it for the blindingly obvious reason that they’re going to need it again tomorrow. Satisfied?”

“You’re the boss, Jack,” Dunn said. “I hope you’ve reckoned the odds, that’s all. I mean, it’s just possible that Jerry’s decided not to use it any more. In which case –”

“In which case he’d close the gap with wire, which is ten times faster and cheaper than mines. Agreed?”

Short pause. “Unless he ran out of wire,” Davis said.

“For Christ’s sake!” Lampard said, pointing. “It’s concertina wire. It’s made to stretch, isn’t it?”

Corporal Harris had been tossing pebbles into the gap. “If we had some prisoners we could send them through to find out,” he said.

“Right, that’s enough talk,” Lampard said. “I go first.” He turned and strode into the darkness.

The others retreated rapidly to the edge of the road and lay flat. Lampard’s figure was a dim blur. “What if it really is mined, sir?” Pocock muttered to Dunn.

“I suppose that will become blindingly obvious, Pocock.”

Lampard reached the gap, crouched and stroked the biggest and freshest of the tyre tracks. They were clean-ribbed and firm. He surprised himself by being reminded of the last time he had touched a woman. He was twenty-four, and women were fun, but war was better. He stood and stared. His body was pumped-up with energy. All his senses were supremely alert, competing to serve him best. He went across the gap in a rush of long strides, heels digging into the tyre track. Nothing exploded. He wanted to laugh and cheer and throw grenades; now he knew he was unstoppable. Achtung! Minen, what a lot of balls! He strolled back, casually and a bit jauntily, hands in pockets, to the middle of the gap. “No problem,” he said. He jumped up and down. “Safe as Oxford Street.”

“My old granny got knocked down in Oxford Street,” Harris muttered.

They followed Lampard in single file.

“Mind you, she was pissed as a fart at the time,” Harris said. Lampard ignored him. They set off, in line abreast, widely spread.

Corporal Pocock was the first to find an aeroplane. They converged on him and walked around the Me l09, touching its skin and sniffing its expensive aromas, the fruity tang of aero-dope and the faint, fairground stink of once-hot oil. Now they could see the silhouette of another 109, and beyond that a smudge of darker darkness that promised a third. Lampard jogged down the line and counted ten fighters. He left Davis and Harris to take care of them and moved on with Dunn and Pocock at a brisk run.

Pocock found the second line of fighters, too. A thin mist was rising, enough to absorb the starlight, but a faint reflected gleam from a cockpit canopy caught his eye. He set down his rucksack and hurried on to find out how many more aircraft were parked here. Dunn and Lampard examined this one. “Pretty new,” Lampard said. “The paint’s still smooth and shiny.” He was standing on a wheel and feeling the engine cowling. “It gets sand-blasted damn fast. What are you looking for?”

Dunn was fiddling with the side window of the cockpit. It clicked, and half the canopy swung open. “I had a thought on the way down that bloody mountain,” he said. “Why not stuff the bomb beside the seat? That way you get the fuel tank. It’s L-shaped, the pilot sort of sits on it. Make a lovely bonfire.”

“If it’s full. Might be empty. Anyway, we want the airframe. That’s the expensive bit.”

“You know best.”

Pocock returned, gasping but triumphant. “Twelve of the buggers,” he said.

“Marvellous. Tell you what,” Lampard said to Dunn, “put half the bombs in the cockpit and half on the wing-roots.”

“A controlled experiment,” Dunn said. “The spirit of true scientific inquiry.”

“Wait for me here.” Lampard jumped off the wheel and made off into the darkness. This is too easy, he thought. Where’s Jerry? No sentries? No dogs? It’s a pushover. A walkover. A cakewalk. A piece of cake. There was benzedrine in his pocket, but benzedrine would be wasted on him now. He saw the massive shape of a bomber. His blood was thumping like jungle drums.

It was a Junkers 88, twin-engined and huge. “You beauty,” he whispered. He decided to place a bomb on each wing, between the engine and the fuselage, but the wing was high above his head. He ran to the tail, took two bombs from his rucksack, and used his elbows to heave himself onto the tailplane. He began to walk forward, but the curved fuselage was wet with mist and he slipped and fell, knowing that he was falling and kicking off so that he landed on his feet and rolled over. That seemed enormously funny. For a few seconds he lay on his back and laughed without making any sound except for a bit of wheezing. “All right, you slimy bastard,” he said. He put the bombs inside his shirt.

Next time he sat on the fuselage, straddling it with his legs, and heaved himself towards the wings. Then it was easy. He stuck pencil-fuses into the bombs, planted them and jumped down. It was all so simple. The more he did, the easier it got.

He found a three-motor Fokker transport with a ladder leading to its cockpit. That got a bomb. Moving fast, he put bombs on the wings of two small aircraft, probably spotter planes, and in the cabs of three massive petrol bowsers which reeked of fuel.

He sat on an oil drum and checked his watch: twenty-three minutes since they came through the gap. The first pencil-fuses had been set for an hour, with the later fuses being shortened as time passed. The night was pleasantly chilly: a night made for action. Lampard felt pleased yet also oddly discontented, almost resentful. He had come a very long way to give the enemy a bloody nose and they were nowhere to be seen. “Pathetic,” he said aloud, and got up and walked back to Dunn and Pocock.

“We’ve done all these fighters,” Dunn said, “and we found something that looked like an ammo dump, so we did that too. Also a great stack of boxes. Probably spares.”

“Good,” Lampard said. He kicked a wheel. “I suppose we might as well go home, then.”

They returned to the first row of fighters. Davis and Harris were sitting on the ground, back-to-back, eating some chocolate they had found in a cockpit. “Any luck?” Davis asked.

Dunn said: “Two dozen planes in all.”

“And a sentry,” Davis said. “Harris found a sentry.”

“That’s that, then,” Dunn said. “Home for cocoa.”

“What’s the rush?” Lampard asked. “I’ve still got some bombs left.”

The others were shrugging on their rucksacks, ready to go. Lampard took his rucksack off.

“Look, sir: we’ve done the job,” Davis said. “Let’s not push our luck.”

“Wouldn’t dream of it, sergeant.” Lampard was counting his bombs. “Two. Anybody else got any leftovers?”

“This place is going to be hopping mad in twenty minutes, Jack,” Dunn said.

“I should hope so. Well?”

“One here,” Pocock said reluctantly.

“I’ve got a couple I was saving to leave in the gap,” Davis said.

“That makes five. Let’s see if we can find some nice big hangars and blow ’em up.”

“There isn’t time, Jack.”

“Then we’d better hurry.” Lampard set off, half-running and half-striding, and the others scrambled to follow before they lost him in the gloom. “This is fucking lunacy,” Davis whispered. Dunn grunted: he knew he needed all his breath to match Lampard’s pace.

Lampard hustled them along for about two minutes, gradually slowed to a walk and finally stopped. “There,” he said. A fine sliver of light appeared, no more than a hairline crack in the blackness. Dunn marvelled at Lampard’s night vision while he despaired of his judgement. Light meant people. “Onwards,” Lampard murmured.

It was a hangar, a steel shell as big as a bank. Davis pressed his ear against the side. Sometimes a muttering of voices could be heard, and the faint click of metal on metal. “Occupied,” he whispered. Lampard led the patrol around the corner. The sliver of light came from an ill-fitting blackout around a huge sliding door. Lampard peered in, but saw only a pile of paint tins. Using the tips of his fingers, he felt his way across the sliding door until he found a small hinged door set into it, and grunted with satisfaction: hangars were much the same the whole world over. Dunn was beside him, tapping his luminous watch. “Fifteen minutes to detonation,” Dunn whispered. Lampard took a deep breath. The air tasted sweet and exhilarating, delicately laced by some aromatic desert herb. Before his mind made the decision, his fingers had turned the handle. It opened inwards, as he knew it would. He knew everything, and the knowledge made him smile with delight. The enemy was there to be beaten. All it took was nerve and Lampard had nerve galore.

He sneaked a glance around the blackout curtain hanging inside the door and saw bright lights over broken aircraft and deep shadow elsewhere. Lovely. He slipped off his rucksack and primed all the bombs with fifteen-minute fuses. He put three in his tunic, took a bomb in each hand and strolled into the shadows. His rubber soles made no sound on the concrete. For a long moment he watched Germans in white overalls doing things to the guts of the engines of two 109s. In another area, men were fitting a new propeller. They seemed relaxed and happy in their work. He strolled on and came across an aircraft with no wings or wheels, supported on wooden trestles. He left a bomb in its naked engine. Nearby was a stack of wooden crates, each stencilled with MB and a serial number. MB had to mean Mercedes-Benz. He found a gap in the stack and left two bombs deep in the middle. Someone shouted a challenge. Lampard ducked and stopped breathing. Now we fight! he thought; but the shout went on and on and became the opening phrase of a snatch of opera. Other men joined in, until they were all thundering out the Toreador song from Carmen. Lampard planted his last two bombs, one on a mobile generator and one on a tractor, and strolled back through the shadows to the door, pom-pomming along with the singers because he didn’t know the words.

Dunn had the door open, ready for him. “Jerry’s getting jumpy. He had a searchlight on, sweeping the field.”

“We might as well leave, I suppose.”

“Through the gap?”

“Where else?”

“We’ve only got eight minutes.”

“Ample.”

“They’ll see us when the bombs go off.”

“They’ll panic when the bombs go off.”

“You know best, Jack.”

The rest of the men began moving as soon as they saw the officers coming. Lampard used a luminous compass to find a bearing to the gap in the wire. After a hundred yards they reached a tarmac road. “Good,” Lampard said. “This is faster.” His eyes were feeling the strain of looking five ways at once, but his legs and lungs were strong, and he enjoyed marching fast on the smooth surface. He could scarcely hear the faint tread of boots, but he knew exactly where his men were. They were spread behind him in a loose arrowhead. Dunn was on the far left, Davis the far right, Pocock at the rear. Harris was nearest. High time Harris got made sergeant, he decided. A decoration would be wasted on Harris, but he’d like the extra stripe. And the pay. That thought flickered through Lampard’s mind while he glanced at his compass. He reckoned the time remaining on the fuses. He pictured the gap waiting ahead and the steep escarpment of the Jebel. At that point he strode into a dazzle of headlights that stopped him like a blinding brick wall.

For a few seconds the only sound was the panting and heaving of the patrol. Sergeant Davis spat. Faint shreds of mist drifted across the dazzle. Lampard squinted hard and began to make out three sources: probably headlamps and a spotlight. “Good evening, gentlemen,” said someone in a voice that was urbane and confident, like the head waiter at Claridge’s. “Weapons on the ground immediately, please. Then take two paces forward and lie flat.” Nobody moved. Lampard cocked his head. Five hundred miles away an orchestra was playing Mozart. Very faint, but quite unmistakable.

“Naturally you are surrounded.” A tiny click, and Mozart died. “Unless you surrender, I regret that you must be shot where you stand.” The regret sounded formal but genuine, like Claridge’s turning away a gentleman without a necktie.

Still nobody moved. The initial blindness had gone, but the dazzle was painful and it made the surrounding darkness twice as dense.

“I’m going forward,” Lampard announced without turning to the patrol. “If I am fired upon, you will blow this vehicle to bits. Understand? Never mind me. One shot, and you destroy the vehicle totally and immediately.” He had the sensation of being outside himself, watching and hearing these orders being given. He stepped forward and the sensation vanished.

It was an Alfa-Romeo open tourer, very big. A Luftwaffe major sat behind the wheel. Nobody else was in the car. Lampard stood on the running board and looked around. Empty ground. “You don’t half tell whoppers,” he said. “Now kill the lights and jump out.”

The major pressed switches and the night flooded back. “I may take my stick?” he asked.

Lampard opened the door. The major had some difficulty getting out. By now Sergeant Davis and Corporal Pocock had moved out wide to guard the flanks. Harris searched the German for weapons: none. Dunn said: “I make it three minutes, Jack.”

“More than ample. We’ll take this splendid car.”

“We can’t leave him,” Dunn said.

“Let me kill him,” Harris said.

Lampard said: “Yes, why not? Silly sod’s no use to anyone. Completely unreliable.”

“To escape, you need me,” the German said. Harris had his fighting knife ready, its point denting the man’s tunic just below the ribs. “Go without me,” the major said, “and all will be killed by the mines.” His voice was calm and steady, as if to say: Take it or leave it.

“Nuts!” Dunn said. “We got in, we’ll get out again.”

“I think not. When you got in, our minefield was ausgeschaltet.” He frowned for a moment. “Off-switched. Switched off. You see, our mines are activated by electricity. Now the minefield is active since ten minutes. I myself have turned the switch.”

Lampard nudged Dunn. “What d’you think?”

“It’s possible.”

Lampard stared down. The German’s face was nothing in the night, but his voice had been firm. “Why bother?” Lampard asked him. “What’s the point?”

“Two minutes five,” Dunn said.

“I shall require more than two minutes five to explain our system of airfield security,” the major said. He sounded slightly amused.

“Okay, forget it.” Lampard turned away and plucked the car’s radio aerial. It vibrated noisily, so he stopped it. “You said you could get us out of here.”

“I said that I can try.”

“Oh-ho. You can try. Now why would you want to do that?”

“Jesus Christ.” Harris was sheathing his knife. “Who cares?”

“I care, corporal. I’m not accustomed to being helped by the enemy.”

“It is better than death,” the major said. “Even to a German officer, death is not welcome.”

“Those fuses aren’t tremendously accurate, you know,” Dunn said.

“What’s your idea?” Lampard asked.

“We go in this car and depart through the main gate,” the major said. “I drive. The guards never stop my car.”

“No. I’ll drive. You sit beside me. Let’s go.”

“No. Not a good idea.” Davis and Pocock had come in from the flanks and were scrambling into the back seats, but the major did not move. “Better I drive.”

“If you drive we might go anywhere. Straight to the guardroom, for instance.”

“And then you shoot me.”

“Anyway, I can drive faster than you can.”

“I well know the road. Do you well know the road?”

“Fuck my old boots!” Harris muttered. “I’ll drive and you two can stay here and argue.”

“Take that man’s name, sergeant.”

“This car is mine,” the major said. “The guards see you driving and at once they think, hullo, something smells of fish.”

Lampard opened the door and helped him get in.

“That is good.” The major started the engine.

Lampard vaulted in and sat beside him, tommy-gun across his legs. “Fishy,” he said. “The word is fishy.” The car moved off.

“You agree, then.”

“Faster,” Lampard told the major. The car swung right and left, found a straight, picked up speed. “I may shoot you anyway when we get out,” Lampard said. “Just to calm my nerves.”

“He’s frightfully nervous,” Dunn said to the major. The major smiled.

He drove fast, on dipped headlights. In much less than a minute they were approaching a pair of striped poles across the road. A guard stood in the soft, yellow light of a hurricane lamp; behind him the guardhouse was dimly visible. The guard had a rifle, but he slung it on his shoulder when he recognised the car, turned away and leaned on the counterweight to raise the pole. The major slowed, gave an economical wave, and accelerated through the gap. “Too easy,” Davis said. “Let’s go back and do it again.” The major worked up through the gears with familiar ease. A mile away, a flash blew a golden hole in the night, and then a bang like a thousand fireworks caught up with the car. The men in the back turned to watch. Lampard watched the major. The major watched the road.

A mile and five explosions later, Lampard said: “This is far enough. Get off the road and drive towards the Jebel.” The night was dancing to the flames of blazing aircraft.

The major slowed, but only slightly. “You wish seriously to walk up the Jebel?” he asked. Two trucks raced past them, sirens screaming, heading for the field. The rapid thumping of anti-aircraft guns began. “Just do it!” Lampard shouted. The major changed down a gear. “I know a track,” he said. “A motor track.” A brilliant flash that exposed all the countryside was followed by a dull boom like the slamming of a castle door. “A good motor track,” he said. The entire castle collapsed and the wallop of its destruction washed over the car so violently that everyone flinched. “Bomb dump,” Pocock said, pleased. Lesser thuds and crumps followed. The major changed down again. “I myself have used this track in daylight,” he said. “But you perhaps will rather climb into the Jebel on foot.” He changed down again. Now they were crawling.

“All right,” Lampard said, “we’ll try this amazing track of yours. No lights. I don’t want the Afrika Korps watching to see where we go.”

“Alternative illumination has been provided,” the major said. The sky over Barce aerodrome pulsed and flickered with a red and yellow glow that grew steadily brighter.

He crossed the plain and found his track. The ruts did not match their wheels, and the potholes were as big as buckets. The major charged the car at the hillside as if it were a challenge. Rocks jumped up and savaged the chassis, and the springs groaned under cruel and unusual punishment. The track twisted as it climbed, twisted as it dipped, twisted as it twisted. Later it got worse. Long before that, Lampard had dropped his tommy-gun and was working hard to protect himself from the rush of shocks.

When they topped the crest of the escarpment he shouted, and the German let the car run to a halt. Lampard reached across and switched off the engine.

Corporal Pocock wiped blood from his nose, mouth and chin. “You tryin’ to start a war or somethin’?” he demanded thickly. Blood continued to flow.

“Stop whimpering,” Dunn said.

“Boots off,” Lampard told the major.

“You tear I will run off?” The major got out and took his boots off and gave them to Lampard. “There is little risk of that.” Lampard looked. The heel of the left boot was built up about three inches.

“Why don’t we let him go?” Corporal Harris said. “Let him walk down the mountain in his socks?”

“Search him,” Lampard told Davis. The sergeant rummaged in the German’s pockets, and a small heap of papers and possessions accumulated on the ground. “Back in the car,” Lampard ordered. He scooped everything up and examined it, piece by piece, in the soft light of the dashboard. “You’re a major in the Luftwaffe,” he said.

“So? I feel like a prisoner of the Brit

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...