Juliets are more trouble than they’re worth. We have never yet hired one who did not bring some spectacular disaster down upon the company, and quite often herself. Every time, Tommy does his best to choose the soprano who seems sane, quiet and smart enough not to waste the opportunity, and, still, something goes terribly wrong. Our first eloped with the tenor in Chicago. The second took sacred vows at a convent in Boston. And then there was the third Juliet. It’s enough to make a Romeo wonder—and certainly enough to make a diva take other operas on the circuit.

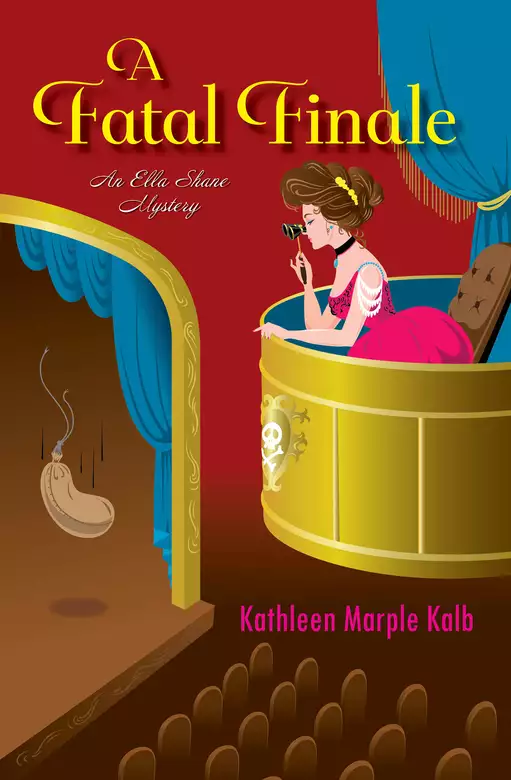

This time, New Haven was the last stop on the tour, leaving us just a short train ride from home in New York and my next bookings in the City. We’d sold out Poli’s Wonderland for the run, even though we had played it just two years before, admittedly with a different repertoire. The Bellini I Capuleti e i Montecchi is always a winner, and there are still plenty of people willing to plunk down good cash money to see trouser diva Ella Shane in her most famous role. And I’m quite happy to oblige them. I didn’t grow up with nearly enough to afford pretensions.

Besides, I like Romeo. While I’m nearly twice his age now, the score is wonderful and the role, of course, is a great deal of fun for me, and, better, for the audience. Yes, I know that there’s the whole frisson of an attractive adult woman in doublet and hose making operatic love to the soprano, but I am not responsible for what people think in the dark of the theater. I know who I am, and am not, and I love putting on a good show.

That icy night in February 1899, I was just hoping that my latest Juliet would behave herself in the final duet. Miss Violette Saint Claire (who almost certainly was not born with that name, not that Ellen O’Shaughnessy can throw stones) had been doing her level lightweight best to overshadow me. First, I had gently pointed out that the audience gets a better show if we all work together. When that proved fruitless, I had Tommy rather less kindly remind her that the marquee says “Ella Shane Opera Company,” and when it says “Violette Saint Claire,” she can chew all the scenery she likes.

In the wings, preparing to walk out into the footlights, I was trying to think about the music and my technique, and not her escalating overacting. For Heaven’s sake, I thought irritably, it is almost the twentieth century. We do not need the florid nonsense that people used to find acceptable in the 1830s.

I am, naturally, well aware of the irony of an opera singer complaining about overacting. But as Tommy’s been known to say, I know it when I see it. And indeed I saw it that night, as Violette sang her little heart out, climbing all over me, and making sure the audience got a much better look at her sweet, heart-shaped face than mine. Too bad this one didn’t run off with the tenor.

Not that I was worried about the competition; while she was undeniably lovely, with black hair, pale blue eyes and perfect white skin, I’m not exactly unappealing myself. Tall, of course, with greenish-blue eyes and, thank you, naturally blond hair with a reddish cast, all perfectly set off by my midnight-blue costume. Though, when the curtain is down, I’m more likely to be smiling, or laughing at Tommy’s latest joke, than cultivating the soulful look you might have seen in my cartes de visite.

At least it was quiet at the moment. After the intermission, there’d been some kind of donnybrook among the young stagehands. It had happened before, though not in usually professional New Haven. This scuffle wasn’t especially serious, unlike the incident in Cleveland where one hand tossed another right into the orchestra pit, ruining the rehearsal, the timpani and his career in the performing arts.

Tonight, though, all I’d heard was a treble voice yelling, “Take yer hands off me, ye nathrach. I’m done wi’ ye!” and some running footsteps.

If it had gone any further than that, I’d have had to ask Tommy to have a word, which I absolutely did not want to do. From the accent, the boy was fresh off the boat, probably from Scotland, and he almost certainly could not afford to lose his livelihood.

In any case, I had other concerns just then. Beyond the warring stagehands, the aggressively lovely Miss Violette would still be in need of correction later tonight, and I owed the audience my best in the final scene.

Whoever might be the fairest of them all, real talent beats overwrought hopeful every time. I finished my final aria and expired, satisfied to hear that moment of absolute silence from the audience that means they’re truly moved.

As Violette took her turn, I watched her through my eyelashes, suddenly realizing she looked really sick. Jealousy’s an ugly thing, I reflected, only slightly uncharitably, as she collapsed on me with a strangled cry, without finishing her final notes. How very unprofessional, I thought, remembering the many times I’d pushed through all manner of unpleasantness.

She didn’t move during the last few moments of the show, but thanks to the heavy costumes we all wear, I did not realize she wasn’t breathing until the curtain was falling.

“Tommy!” I yelled, thoroughly inelegantly, as I tried to climb out from under her and see what I could do to help.

Tommy Hurley, my cousin, manager, best friend, and rock, ran over from the wings, his usually cool blue-green eyes wide with concern. “What happened?”

“There’s something very wrong with Violette.”

It was one of my more magnificent understatements.

Late April, in Washington Square

“Come on, Tommy. At least try to parry,” I urged, swiping my foil. Really, I should stop practicing my fencing with him, but I didn’t have anyone else at the minute, and it’s like dancing—you have to stay sharp. I usually alternate days between the two, and, no, I don’t even attempt dancing with Toms.

“I’m trying, Heller.” He rarely calls me by anything but the childhood nickname, earned during any number of street scuffles. “Too bad you don’t box.”

“Sorry, Champ”—I pointed, jokingly, to my face—“can’t afford to risk my lovely visage.”

Tommy laughed. He really had briefly been a top fighter, until he decided that no amount of violence would make him the man he wasn’t, and didn’t want to be, and turned his management skills from his career to mine. He’d gotten out soon enough that he still had the muscles and dangerous air, but no noticeable damage to his sharp Celtic features. “Hard to hit the high notes with a bloody nose.”

“Too true.” I moved back into position. “All right, just try to keep up.”

“‘Try to keep up’!” squawked another voice from the rafters as Montezuma swept down toward us.

I like to think of the studio as my domain, but in truth, it belongs to Montezuma, my Amazon parrot. He requires space to fly, and enjoys singing along when I vocalize. Tommy and his sports writer friends are also fond of Montezuma, and, unfortunately, they’ve taught him a few colorful turns of phrase.

Montezuma came with the town house, a condition of sale from the importer who’d owned it, and had given him run of the attic, which the bird kept, once it became the studio. I call him “my” parrot, even though one doesn’t really own such an amazing creature, because he’s attached himself to me. Montezuma flew just over our heads, took a perch at a window and started preening his vivid green feathers with his bright blue beak, enjoying the spring breeze as much as we were.

“There’s someone here to see you, miss,” Rosa, the housemaid, called, running in ahead of a very tall, dark stranger.

“Oh?” I stepped away from Tommy, still holding my foil.

“He says he’s a duke or something.” Her big brown eyes were wide with excitement.

“Everybody’s got a confidence game.” Tommy chuckled as the man walked in.

“Not a confidence game at all, my good man. I am Gilbert Saint Aubyn, Duke of Leith.”

“Of course, you are,” I replied, taking a good look at him. Whoever he was, he was certainly a positive addition to the rehearsal studio. He was several inches over my height, with nearly black hair, ice-blue eyes and enough time on him to make him interesting. Not ostentatiously dressed—a neat black coat over a dark gray day suit, a plain black fedora in his hand—so he might just be something real, and not a swell. But probably just another opera fancier, if at least a creative and nice-looking one, so I decided we’ll give him a minute or two.

“Are you Miss Shane?”

“None other.” I held out my hand to shake, but he didn’t take it. I remembered that British aristocrats are very uncomfortable with the new American ways. The accent seemed right, too; I’d spent enough time singing for my elegant supper in London to recognize the vowels, and pick up a faint trace of somewhere else in the consonants. I put my hand in my pocket, and did my best not to giggle as I realized he was trying very, very hard not to look below my face.

He would not have seen much if he had; I was wearing one of Tommy’s discarded shirts loosely tucked into a pair of dark blue cotton cavalry twill breeches so old I didn’t remember where I’d acquired them. With, of course, the light, but modest, underpinnings any proper lady would wear with such.

“Good. I am trying to gather information on the fate of a young lady. You would have known her as Violette Saint Claire.”

The giggle strangled in my throat. Poor, dead Juliet. The New Haven coroner had ruled it accidental, for the sake of her family, if they were ever found, but since it was real poison in the prop vial that only she touched, we all knew what it really was. “Oh, dear. I’m terribly sorry. Was she a relative?”

“A cousin. I am the head of the family, of course, so I am taking charge of finding out what happened to her.” A muscle flicked in his jaw, and the skin around his eyes tightened a little, the way it does when people are trying not to show too much emotion.

“Well, Your Grace, I don’t know how much you know.”

“I have already seen the report from New Haven. I want to know what she was doing with you theater people.”

Tommy’s eyes narrowed at the last two words, pronounced in a tone redolent with disdain, and the unmistakable suggestion of all manner of impropriety.

I offered a cool response as my sympathy for the Duke of Something died an early death. “‘Theater people’?” I repeated.

“She was a gently-brought-up young lady who did not belong in that world.”

Well, aren’t you the precious one. I took a breath, and tried to tamp down my Irish temper. I explain—if not excuse—my next action as an effort to do something other than slap the judgmental scowl off his face. I grabbed Tommy’s foil. “How’s your fencing?”

“What?”

“My practice time is limited, and we theater people have to stay sharp to earn our keep. I’ll talk to you while we spar.”

Gilbert Saint Aubyn’s stern face softened a bit. “All right.”

He doffed his immaculately tailored coat and suit jacket, with a black armband still on the sleeve, no doubt for poor Violette or whatever her name really was. I had no compunction about taking a good look at him, and was not disappointed with what I saw. I may be a proper maiden lady, but I do appreciate the well-assembled male form, especially in a nicely fitted gray waistcoat, neat white shirt and dark trousers. I tossed him the foil, and he dropped it.

“Good thing we’re fencing and not playing baseball,” I observed, carefully not snickering, in case it was a feint.

Saint Aubyn, who would have been the late, lamented himself if this had been an actual duel, gave me a wry, and rather appealing, shrug. “I have not been on the field of honor in a while.”

“Well, let’s see what you’ve still got. En garde.”

I started on the attack. At first, he was very cautious, clearly uncomfortable with the idea of fencing with a woman. But he quickly realized I was much better than he was expecting, and began matching my parry and thrust. He was far more skilled than you’d have expected from that awkward start, but still nowhere near my level. Thankfully (and entirely uncharacteristically), Montezuma observed all of this without providing commentary. I knew it was just a matter of time.

“What was her real name?” I asked. Still better than fencing with Tommy, who was not always able to hang on to the sword for more than a few minutes.

“Lady Frances Saint Aubyn. Daughter of one of my uncles.”

I let him back me up a bit before I went on the attack again. “She was a very well-trained operatic soprano.” And a rotten little show-off, but we don’t need to go into that.

“A lifetime of singing lessons wasted,” he replied as I forced him back across the studio. “It is supposed to be merely a ladylike accomplishment.”

“Clearly, she didn’t see it that way.” Parry.

“Clearly.” Thrust.

“Singing opera is an honorable profession.”

“Maybe for a woman who has to earn her way in the world.” He nodded as he attacked. “I will give you that.”

“Generous of you.” I met the attack and very nearly twisted the foil out of his hand.

“Well done. I probably deserved that.” He smiled faintly as he backed up and regrouped, then started toward me again. “She ran off two years ago. We got a letter from the coroner of New Haven. I gather you did not know she had a family.”

“No. The last I heard, the authorities were still trying to identify her.” I let him back me up a bit, before launching a new attack. “I am sorry we didn’t know. I would have notified you myself.”

His eyes met mine, cold blue. “Really?”

“Really. I run a respectable company, and I take care of my employees.”

“Not so well, it seems.”

“That’s hardly fair.” Thrust. Attack. “I am sorry about what she did, but we had no indication she was desperate.”

“No?”

“The role was a big break for her. She certainly seemed happy about it. And before you ask, we protect our in-génues.”

“Oh?”

“In every city we stay, they are placed at respectable women’s hotels. And I personally make sure there is no fraternizing.” Since I lost a Juliet to a tenor, but that’s none of his business.

For a few moments, there was nothing but the sound of steel on steel. I clearly had the better of him, but he wasn’t bad.

“You fence well, Miss Shane.”

“You also, Your Grace.”

“I note that you are familiar with the forms.”

“I am an opera singer with a certain following.” I smiled as I backed him off. “I have been a few places and met a few people.”

Out of the corner of my eye, I saw Tommy grinning at that one.

“I don’t doubt it.” Saint Aubyn’s eyes sparkled. “Might we continue this discussion at some other time, perhaps dinner, without weapons?”

At that, I took a good hard look at him over the swords. “I am fond of tea at the Waldorf. I do not go out to dinner with men outside my family.”

His brows flicked up and he almost missed the parry. “What?”

“I told you, I am a respectable maiden lady and an artist, not a chorus girl.”

Tommy was laughing, but hiding it well. Of course, I hadn’t said anything untrue; clearly, the Duke of Wherever didn’t understand.

“Oh.”

I had him almost in the corner now. “It is not my fault that you can’t tell a soprano from a soubrette.”

He half-smiled at that, and backed up, giving me a chance to corner him. “Actually, mezzo, no? Most trouser roles aren’t soprano.”

“I’ll give you that.”

“Well played.” He tried one more attack, but I’d already backed him up too far to recover.

“Draw?” I offered in the interest of diplomacy.

“Draw. Nicely done.”

We bowed.

“Try to keep up!” Montezuma pronounced from above.

Saint Aubyn laughed, completely changing his rather severe features. “Amazon parrot?”

“Montezuma is a very bad boy.”

“‘Montezuma’? My mother’s is called Robert Burns. She’s taught him some Gaelic.”

My turn to laugh.

“He also sings ‘Sweet Afton,’ naturally, usually when Mother is pouring tea.”

We nodded together as I put down my foil, and he tossed his back to Tommy, who caught it with a laugh.

Gilbert Saint Aubyn put his jacket on and favored me with a full, amazing smile. “This was not the conversation I was expecting, Miss Shane.”

“Perhaps you need to adjust your expectations.”

“With the new century coming, I suppose I might.” He nodded to me. “Tea tomorrow?”

“Certainly.”

“I will look forward to it. And not, I suspect, merely for the information I may gather.”

He bowed to Tommy and me, bid us a gracious “good day” and walked out.

Tommy grinned at me as he left. “There goes trouble.”

“That is a fine figure of a man,” I admitted. “Even if he is an English stick.”

“‘English stick’!” crowed Montezuma.

I glared at him.

“Love the birdie!” he called, cocking his head and giving me the closest thing to an adorable smile that a creature with a blue beak can manage. Like any other male of my acquaintance, he had to have the last word.

That evening, Tommy and I were alone for dinner, and so, for that matter, was Montezuma, since he was happily devouring seeds and carrots in the studio, as he did at most mealtimes. While Montezuma wasn’t welcome in the dining room, we would have happily shared our table with Rosa, our housemaid; Anna and Louis Abramovitz, my costumer and accompanist—and their adorable small son, nicknamed “the Morsel”; or even Mrs. Grazich, the cook, for that matter, but they were all at their respective homes (in Mrs. Grazich’s case, probably unwilling to break protocol by eating upstairs). Though we shared the comfortable and respectable town house in Washington Square these days, we both remembered far less happy bed and board down in the tenements of the Lower East Side.

Tommy’s mother, my aunt Ellen, took me in when I was barely eight, after my mother finally succumbed to the consumption she’d been fighting, as long as I could remember, and went to join my father. All I had of my father was his name, and my mother’s stories of the beautiful redheaded Irishman she fell in love with while standing in line at immigration. An outbreak of typhoid carried him off, just about a year after they had married over the objections of almost all of their world. He’d lived to see me, and hold me, and that was about all. It was enough for her.

I had more of her, including the Sabbath candlesticks that my aunt had amazingly allowed me to light every Friday night, even though she made it clear to the rest of her very Catholic brood that it wasn’t something for them, and I still went to Mass to keep up appearances. By then, I knew enough about the world to be grateful for her understanding, and hope that whoever was in charge of the next world, they were kind enough to let my mother and father be together.

I’d always had an ear for music, singing while I worked, which was mostly helping Aunt Ellen clean houses for what we’d have called “our betters.” I was ten when I happened to be dusting a piano one day at a lady’s house when she heard me, and sat down at the bench.

“Sing for me, child. I’ve never heard anything like that.”

The lady turned out to be the “respectable” sister of Madame Suzanne Lentini. Yes, that Lentini. Within a month after that day, I was dusting Lentini’s piano in return for singing lessons. At first, I was just a pet, like a lapdog with an unusually good party trick. But I turned out to be a coloratura mezzo instead of a soprano like her, and so no threat as a protégée. Even better, I shot up to my full height early. Lentini and her manager, Art Fritzel, realized a tall girl with a big voice and the scrappy attitude to carry off a boy’s role could be a sensation. And indeed I was.

A word here about “trouser roles, ” with an apology for the inevitable indelicacy. A couple of hundred years ago, there were a good number of castrati, men who’d been, well, un-manned, to keep their voices high. In our modern age, thankfully, we do not believe in such barbarism. But there were a good number of heroic roles written for these unfortunates, and someone has to sing them. Which brings us to me, a woman who has the vocal range to sing the part well, and the acting ability to perform believably enough.

I don’t doubt that some people, men, in the audience are more interested in the frisson of an attractive woman in trousers, especially since there is no other respectable circumstance where a man might see a woman’s legs in public. But this is opera, not the dance hall, and I am responsible only for my art, not what people think. Anna always makes my costumes with modesty in mind, and I am very careful to avoid vulgarity in my movements, so, really, any ill you may see is entirely in your own mind.

Lentini was my first Juliet, when I was still Romeo’s age. I spent the next several years playing the opera houses in the City, occasionally going on the road with Lentini, including an amazing London run, and even a few solo bookings.

Everything changed when Lentini and Fritzel decided it was time to retire together to the Amalfi Coast, an absolute lightning bolt to anyone used to watching the regal diva and her small, scruffy manager argue about quite literally everything. Tommy had just defended his title with an impressive win, but I knew he was wretchedly unhappy, despite it all. I had several offers from companies in the City and elsewhere, but none felt right. I wasn’t at all sure what I would do with myself without my mentors, until I met up with Tommy after a sparring session one afternoon, and it all suddenly fit together. He had an old trainer who served as his official manager, but he did most of his own bookings, logistics and other things, being the smart Irishman on the make that he is.

We were walking back to the small, but comfortable, house where we’d ensconced Aunt Ellen and the younger ones (Uncle Fred was gone by then) when I looked hard at him.

“You’re not happy.”

“I’m a champion. Nobody will ever call me a ‘sissy’ again. What’s not to be happy?”

That was true, as far as it went. He had spent a couple of terrible years on the wrong end of street scuffles before he grew seven inches in six months and started boxing. The tenement toughs sensed something different about him, whether it was his kindness to me, his. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved