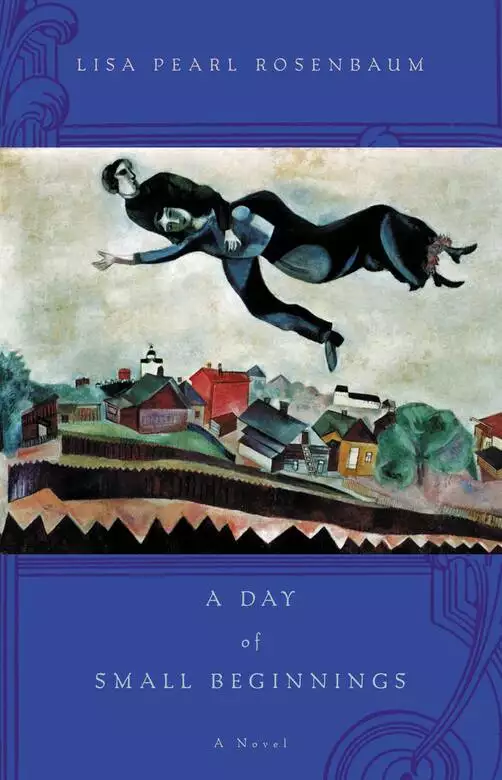

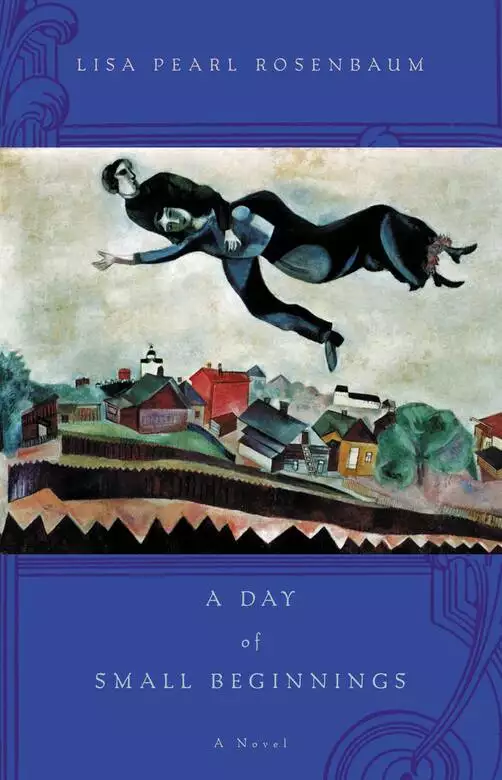

A Day of Small Beginnings

- eBook

- Hardcover

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Poland, 1906: on a cold spring night, in the small Jewish cemetery of Zokof, Friedl Alterman is wakened from death. On the ground above her crouches Itzik Leiber, a reclusive, unbelieving fourteen-year-old whose fatal mistake has spurred the town's angry residents to violence. The childless Friedl rises to guide him to safety -- only to find she cannot go back to her grave. Now Friedl is trapped in that thin world between life and death, her brash decision binding her forever to Itzik and his family: she is fated to be forever restless, and he, forever haunted by the ghosts of his past. Years later, after Itzik himself has gone to his grave, his son, Nathan, knows nothing of his bitter father's childhood. When he begrudgingly goes to Poland on business, Nathan decides on a whim to visit his ancestral town. There, in Zokof, he meets the mysterious Rafael, the town's last remaining Jew, who promises to pass on all the things Itzik had failed to teach his son - about Zokof, about his faith, and about himself.

Release date: August 1, 2009

Publisher: Little, Brown and Company

Print pages: 368

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

A Day of Small Beginnings

Lisa Pearl Rosenbaum

and recited the Psalm of David: What do You gain by my blood if I go down to the Pit? Can the dust praise You? If God’s answer was punishment for my sins or praise for my good deeds, I cannot say.

Understand, I did not call Itzik Leiber to my grave that spring night when my return to the living began. The boy had already

jumped the wall of our cemetery, our House of the Living, as we call it. He was down on all fours, like an animal, looking

for a place to hide. What’s this? I thought.

Sleep, Freidl, sleep, I told myself. An old woman like you is entitled. What did I need with trouble? I was a year in the

grave. My stone was newly laid, still unsettled in the earth. I had no visitors. In death, as in life, people kept their distance.

In our town, a childless woman’s place was on the outside.

And yet, from the hundreds of gravestones that could have hidden him that night, Itzik Leiber chose mine. His knees, his toes

dug into the earth above me. His fingers scraped at the bird with open wings engraved on the dome of my stone. He panted and

he pushed against the indentations of my inscription like an insistent child at an empty breast. Freidl Alterman, Dutiful Wife, it read there, as if this explained the marriage.

Itzik Leiber’s small, skinny body smelled of fear’s sweat and the staleness of hunger. But through his fingers his soul called

out to me. Plain as a potato, his soul.

From the outside, he didn’t look like much either. A poor boy, maybe a year past his Bar Mitzvah. He had a head the shape of an egg, the wide end on top. And kinky brown hair, twisted up like a nest. His cap was so frayed

the color couldn’t be described. But under the brim, the boy had a pair of eyes that could have made a younger woman blush—big,

sad ovals, and eyelashes like feathers.

I remembered him, of course. In a town like ours no one was a complete stranger. Itzik the Faithless One, they called him.

Faithless? I can tell you Itzik wasn’t faithless that night, not when he whispered against my gravestone, his voice thin as

a thread, “Help me! Please, God, help me!”

God should answer him, I thought. A child’s tears reach the heavens. Listen to the boy and leave me to my rest, I prayed. But God had other ideas. Rest would not return to me. Itzik wrapped his arms around my stone, his body curled there

like a helpless newborn. How could I ignore him? I wanted to cradle the petrified child, to make him safe.

In life I liked to say, God will provide. But who could imagine He would wait until after I was gone to the dead to provide

me with a child? Such a joker is God.

A night wind gathered like a flock of birds around our cemetery wall and swept through the thick confusion of graves. The

soft soil began to pound above me with the heavy tread of men. They were so near I could feel their boots making waves in

the earth. What had he done, this Itzik of mine, to incite the Poles to come out so late at night?

Raising myself, I saw torches in their hands, murder on their faces. The faint whiff of alcohol floated over our neighbors

like a demon. You never know what a Pole will do. One minute he’s ready to kill you, the next he’s offering to sell you apples,

smiling, ingratiating, like nothing’s happened. There were as many Poles in our town as there were Jews. But we never counted

them among us, and they never counted us among them.

Itzik whimpered. He gripped my stone with a frenzied, furious fear. His eyes rolled toward heaven. Make them go away, he prayed. In the moonlight, his breath formed sharp white puffs that disappeared in the shadows of the gravestones.

I prayed too. God help him, I said. Give the boy’s poor soul a chance to cook, to become a man.

What else could I do for him? I knew I was no dybbuk that could invade the world of the living. I had made my journey to Gehenna already and eaten salt as punishment for my pride. About this, all I can say is that at least for me it was short, not like

for the worst sinners, who stay in that place eleven months, God forbid. After my time there, I returned to Zokof’s cemetery

to sleep with my earthly body and to wait for Judgment Day.

Itzik pulled at my gravestone so hard it fell over at his feet and broke in two. Who could have imagined that a boy’s clumsiness

would stir me so? My soul tugged and beat at me. Gevalt, how it struggled to tear itself from death’s sleep. Such a sensation—frightening and wonderful—the feel of it pushing upward,

freeing itself from the bony cavity once softly bound by my breasts.

I asked God, Is this life or am I again in Gehenna? I never heard of such a state as I was in. But fear was not in me. When

my soul was finally released from my resting place, I hung like a candle-lit wedding canopy over Itzik’s unsuspecting head.

In my white linen shroud, my feet bound with ribbons, I felt lovely as a bride and as proud and exhausted as a mother who

had just given birth.

A tree near Moishe Sagansky’s grave gave a snap. So new was I to being among the living again, I could not be certain who

did this, me or God. The Poles stopped to listen; then one of them looked in my direction and began to holler, “A Jew spirit’s

out!” They took off. Just like that. Such a blessing that the Poles of Zokof were scared of dead Jews. If only they were so

scared of live Jews, maybe we’d have had less trouble with them.

My Itzik, terrified boy, lay stiffly on the ground until silence returned. He crawled to Ruchelle Cohen’s tall stone, and

without so much as a glance at the carved floral candelabras engraved there, he swiped a pebble that had been placed on top

by one of her children. With the loving care of a son, he laid it on top of my fallen stone, respecting my memory. Regret

at my childlessness passed through me again. When Itzik rose, unsteady as a toddler, I could not help being moved by him.

He held out his arms and unrolled his clenched fists. Grass fell from his fingers.

I shook with pain and thanks to God for this boy, delivered late, but maybe not too late. A child, at last. Oh, the joy I

felt! My heart! He had gathered grass for me. I swept close around him, ready to receive his prayer for the redemption of

my soul. I waited for the words: May her soul sprout from this place as grass sprouts from the earth. I waited, pregnant with expectation.

What came instead was a sharp, thin cry, quickly stifled, and the insult of his foot kicking apart the little mound of blades

he’d dropped on my grave.

SWEEP THE HOUSE, PEOPLE SAY, AND YOU FIND EVERYTHING. When the Angel of Death came for me I was a widow already. My husband, Berel, was four years under his stone on the men’s

side of our cemetery. The attendant from the Burial Society took the feather from my nostrils and said I breathed no more.

“God has taken our Freidl, smoothly as a hair removed from milk,” he said. My neighbors opened my windows and covered the

mirrors so that no ghosts would be captured. They came to ask my pardon for shunning me, a barren woman. They recited the

psalm, He shall cover you with His feathers and you shall find shelter under His wings. But they did not find the secret I had kept inside my house all those years.

I was not barren. All my life it was plain to me that my womb could have held a score of babies. My breasts could have suckled

children and delighted an attentive husband. But from the day we stood under the wedding canopy, my husband, Berel, could

not perform his marital duty.

Her conjugal rights a husband shall not diminish, God commands married couples. Sabbath evenings, those first weeks, we went to our bed with pure thoughts, knowing it was

a holy thing to make a child. But Berel’s seed came too fast, or not at all. In the beginning I thought it was my books that

drove away his desire. A woman should not be more learned than her husband, my mother always said. I put my books out of sight

and discussed with him only household matters. This changed nothing between us. I watched for signs that he wanted someone

else. But my husband did not look at women, plain or beautiful. After not even a year, he stopped with me entirely.

I admit the sin was mine, lying for a husband who had defied God’s commandment to be fruitful and multiply. The Talmud teaches

that our abstinence was like shedding blood, taking life. I should have brought my case before the elders of our community

and pleaded to end the marriage. I could have argued it was his share to love his wife at least as much as himself, to honor her more than himself. But if I had brought about the end of

the marriage, what a scandal for us both.

Instead, I hid his shame. At first I hid it out of pity, though, God forgive me, in time my pity turned to disgust. Later,

I hid it because I realized I didn’t mind so much, being childless. I could study in peace, like my father. I prayed to follow

in the tradition of Edel, the Baal Shem Tov’s daughter, a woman of such valor and intellect that all who met her said the

Divine Presence shone on her face. To me, it was an impossible combination that Edel was also a mother, who raised the brilliant

Feyge, mother of the Storyteller, Nachman of Bratslav. I thought I was a woman who would only lose herself in mothering and

come to resent her children. Not for me, to let my books gather dust in the corner while I slave to feed twelve children,

like Ruchelle Cohen, all worn out at fifty.

Twenty years into the marriage, when it was too late to make a change, I realized I had not only disobeyed His commandment

to be fruitful and multiply, but also turned my back on my own nature by not becoming a mother. There was part of me that

would never grow because of this. What was the purpose of all my study if it did not reach a new life I had tended? Whose

mind would I shape, like my father had done for me? Whose hands would take up the penknife and the board, my secret pleasure,

and glorify our God with intricate oissherenishen—my paper cutouts?

A woman has no right to be so bitter about her husband. She is his helper in life, his footstool in heaven. That is God’s

will. But for the rest of my life hot, painful anger at my childlessness stirred me up inside. Not a day went by that I did

not taste the sin in this and serve it to my husband like a poisoned meal. Eventually, it killed the marriage.

At his funeral, I was a dutiful wife. I hired the mourners to tear their hair and wail for him. But I stood silently at his

grave, the anger reawakened by the finality of my loss.

At the moment of my death, regret rose again like a demon, and I refused to be still. When the mourners placed my body in

the ground, seven blades of grass beneath it, and proclaimed over me, Blessed art Thou, the True Judge, I argued with God for more time to redeem myself. Let me teach someone what it is to love You. Let me pass just that much on, I begged Him.

God’s answer, I believe, came to me on that cold spring night, one year later. Itzik.

Of him, I knew certain things. I knew they said Itzik’s mother was a pious woman, a woman who gave money to Rebbe Fliderbaum

for the yeshiva. This she did even after her husband, Mordechai the Ragman, left her for who knows where. Five young children Sarah Leiber

had to feed, poor soul. People said the Leibers would have starved if Itzik hadn’t left school and gone to work at Avrum Kollek’s

mill.

Everyone agreed it was all for the best that Mordechai the Ragman had abandoned his family. The man had dressed like a Hassid,

but he’d been no blessing for a husband. What kind of Hassid, what kind of person, boasts in shul that he’d stamped his muddy boots on his wife’s wedding dress just to show her what’s what? Their neighbor Rivka Fromin said Mordechai called the poor woman a crazy cow in front of her children. Such a father must

have made Itzik feel like an orphan even before the man left home.

After, when his father was gone and Rebbe Fliderbaum came by to offer the family help, Itzik threw the rabbi out of his mother’s

house. Called him a thief. “Prayers don’t feed my family,” he’d said.

So people called him Itzik the Faithless One. Faithless? Anyone could see the boy was just angry at his father. Anger like

this is passed down, generation to generation. Mordechai the Ragman had been angry like that at his father, Yankl the Porter, maybe even became a Hassid to spite him.

But even from so bad a match as Sarah and Mordechai Leiber, good children are born. I followed Itzik when he left my grave.

WHEN THE POLES WERE GONE, ITZIK WENT LIKE A THIEF TO the center of our cemetery, where all the paths connected like spokes in a wheel. Every few steps he stopped and listened.

For myself, what a blessing, what a joy, to float in the air with no effort at all. I settled like a scarf around the inside

of his shirt collar—such a filthy thing. I flew over him, around him, wherever I wanted to go. True, my vision was double

or triple, and the colors were not right. There were too many shadows, and things didn’t look so clear. But at least bad eyesight

wasn’t going to kill me.

As for Itzik, he had no idea I was swooping like a crazy woman around him. Maybe if he had seen me he would not have looked so grim when he pulled the cap over those eyes of his and headed

down the main stone path, past the monuments and mausoleums of the generations. We reached the stones of the Kohanes and the

small marker of our oldest resident, Israel, buried in 1568. I stopped, out of habit, to pay my respects.

We passed the burial house at the entrance. Exalted, I flew outside the iron gates. I turned for a last look at our town’s

House of the Living and got a shock such as I never had in life.

The walls around our sacred grounds had risen into a dome of crisscrossed gray hewn blocks. He, God of My Destiny, Creator

of All Boundaries, had locked me out of my resting place, my Eden. The words of the Book of Lamentations, alive in my memory

as they had been in my father’s study, came to me: He has blocked my ways with cut stones. He has made my paths a maze.

Almighty God, I prayed. What have I done? The boy came to me. Did You want me to refuse him? Show me an opening. Show me how I am to regain my place

among the dead. I beg you, do not condemn me to roam the earth forever. But He gave me no sign, just Itzik.

The boy crept into the shadows of the birch trees that lined the road back to town. Several times he stumbled in the rutted

dirt. He made little grunting noises like a frightened pup, and looked over his shoulder constantly. I watched him, not knowing

what to do, until I realized God had tied our fate.

I quieted myself as best I could. What did I have to fear? I was already dead. I told myself it was God’s will that I listen,

that I understand what He expected of me, what He wanted me to do for Itzik. The boy had reached the outskirts of town. I

flew to him. Pay attention, Freidl, I told myself. He is in danger.

From the stables, Itzik wound his way in the direction of the main square. He kept away from the open sewer on the one side

of that muddy street and stayed close to the houses. Houses? Rats shouldn’t have to live in such places. Decayed wooden hovels,

halfway to falling down, shutters broken with Jewish poverty and gashed by Yudel the Teacher’s hammer. Six days a week Yudel

would bang at those shutters until the mothers gave up their reluctant boys for a day of study at his miserable cheder.

Passing Chaim the Baker’s shop, Itzik ran his fingers along the ledge on the half door where Chaim stacked bread for sale

during the day.

A dog barked. Itzik jumped for the shadows of Velvl the Water Carrier’s lopsided shed, its roof nearly collapsed. I hoped

maybe he’d stop there at Velvl’s. Velvl was as pious and wise as he was poor. But Itzik circled back to the main square under

the shadows of the walls. He tripped on a stone doorstep and cried out in pain when it split open his right boot. I could

see the bare toes. The night air had gotten cold, and he shivered. Please, God, he whispered.

Please, God, I prayed also.

A few doors off the main square, he stopped in front of the two-story brick house of his employer, Avrum the Flour Merchant.

Now, Avrum Kollek was one of the richest men in town, but he was the kind of man who acted from the heart only when it concerned

his immediate family, a man who gave to charity because it is written that he had to, who made a big show when he gave the

shul a new prayer book. Not a bad man, understand. But not a man to count on.

Itzik hesitated on the stairs. I could see he had his concerns about Avrum too. But he lifted his head, took a short breath,

and stepped up to the doorway. For a long time he knocked softly on the thick wooden door, as if he knew Avrum wouldn’t welcome

the sight of him. Receiving no answer, he knocked louder.

“Who’s there?” Avrum called.

“Itzik Leiber,” the boy answered, digging his fingers into the palms of his hands.

Avrum opened the door and stuck out his bushy head. “What’s going on?”

“Please, let me in,” Itzik whispered.

A goose honked somewhere behind the house. It startled them both. Avrum patted his yarmulke, a habit that gave him time to compose himself. “What do you want from me at this hour?” He tugged at the great leather truss

with the brass clasps that his wife, Gitl, may she rest in peace, said he always wore. “The ache from the truss lets him ignore

the sorrows of others,” Gitl always said. “I’ve got pains of my own,” he would tell the beggars.

“It was an accident, Avrum Kollek,” Itzik began. “It was the Pole who sells you wheat, Jan with the broken teeth, the one

who laughs.”

I came close as a breath between them. An accident with Jan Nowak was no small thing. The peasant was a born troublemaker,

but no one could cross him. His father, Karol, was famous in our parts. He claimed he’d seen the Virgin Mary over the Tatra

Mountains, and his people believed him. Why not? Every town needs a hero. Of course, if I drank as much as Karol Nowak, I’d

have seen Moses crossing the Vistula.

Avrum looked like a horse that had been reined in hard. His eyes went a bit wild too, as if he was about to rear. “Come inside.”

He checked the street over Itzik’s shoulder and pulled the boy across the threshold.

Itzik stood in the corner of the salon, his cap in hand. When Avrum lit a kerosene lamp, Itzik barely moved. He sneaked looks

from the sides of his eyes at the patterned carpet and the framed photographs on the fleur-de-lis wallpaper that was once

Gitl’s pride.

“Shuli, come quick!” Avrum called.

Itzik’s eyes shot back down to the floor.

Avrum’s daughter came out from behind the double doors on the other side of the room. Her blue shawl was wrapped tight around

her shoulders, from cold or modesty I couldn’t tell. In the year since I’d been gone, she’d become a woman, a beauty with

pink cheeks and her mother’s thick dark hair.

God forgive me, but I’d wished a pox on Avrum Kollek many times because of this girl. Imagine, he sold vodka to peasants so

he could buy her fancy dresses. When people told him to stop, that he was endangering the whole community with such dealings,

he threw up his hands. As if it had nothing to do with him when those same peasants got drunk and beat up Jews. But to see

Avrum now with his daughter, I understood him better. The man was still amazed he’d produced such a lovely child. It blinded

him to the dangers.

“Close all the curtains and light the lamps, my shayna maidel,” Avrum said, with a tenderness I’d never heard in his voice before.

Shuli did as she was told, but not before her eyes stole wistfully over Itzik. She reminded me of how, as a girl, I’d looked

at my beloved Aaron Birnbaum. Better she shouldn’t look, I thought. Longing for a boy who was out of the question as a marriage

match could only bring bitterness between a father and his daughter. My love for Aaron had cost me the faith that my father

was my truest ally. He knew Aaron Birnbaum had won me with his tunes and his kind, intelligent face. But he chose Berel, a

man who, as he put it, had only a taste for Torah but a butcher’s steady income. My father said it was his duty to make me

a good match, not a happy one, especially in perilous times. In my father and Avrum Kollek’s eyes, Aaron and Itzik might as

well have been Poles.

Shuli loosened her shawl, let it slip just enough to show a little more of her nightdress. It was a bold move, in front of

her father, but a brave one. Sometimes the heart does what it must. I wondered if Itzik had it in him to grasp what had just

been offered. But he was staring at his image in the mirrored doors of the enormous mahogany wardrobe, as if he’d never seen

himself before. Something about the way the boy stood, with his shoulders hunched inward, made me think that even if he was

here on less serious business, this girl would be wasting her time on him. He didn’t know about women yet. Maybe he never

would. It was that raw, potato soul of his. Or maybe Yudel the Teacher had done his work on him in cheder, telling the boys

if they looked too much at women, they’d hang by their eyebrows in the fires of Gehenna.

Shuli paled at Itzik’s inattentiveness, and I felt the familiar nick of heart sadness. She offered him a last look, but receiving

no encouragement, she just wilted, poor girl, closed her shawl back around her body, and sank into the upholstered green chair

by a small table.

“Nu?” Avrum said.

Itzik stared at the floor.

“Well?” Avrum repeated more loudly. He was so impatient with the boy, he didn’t see Itzik’s anger. But even through the veil

of my blurred vision, I could see that anger was something this boy knew well, an old companion who gave him strength and

comfort, whose smell was as familiar as his father, Mordechai the Ragman.

Itzik looked up at Avrum. “I stopped him,” he said slowly, defiantly.

“Stopped who?”

“Jan Nowak.” He twisted his cap uncomfortably. “It was an accident. The grass was wet. He slipped. The horse pulled the wagon.”

“Grass? What are you talking about?” Avrum clapped his hand on Itzik’s shoulder. “You’re talking like a meshuggener, boy. What’s happened?”

Itzik winced. “Please, Avrum Kollek! I was on the Gradowski road tonight. I had to get wool for my mother, from Kolya Ostrowski’s

farm.” Itzik looked desperate.

Avrum let go of his shoulder. “And?”

“I saw Jan Nowak and his wife in their wagon.”

Now Avrum looked completely confused. “You wake me up in the middle of the night to tell me who you saw on the road?” But

I could feel his fear. It pulsed from his temples to the back of his neck and down his back.

Itzik had his eyes on the floor. “They were out there on the road, on their way home from Yudel the Teacher’s. Tzvi Baer,

Chaim Apt, and another one—I didn’t see his face in the dark, but he was maybe three or four years. They had Yudel’s kerosene

lantern. It was hitting the ground. They couldn’t carry it without bending their arms, and they were too tired to hold it

up.”

This was how it was for the boys in our town. The men insisted on the tradition of sending them to cheder when they were three

years old, but what a pitiful thing to see these little ones, barely awake on their baby legs, traipsing home down dark roads

at ten at night after a day of sitting on hard benches, reciting Hebrew without understanding, taking blows from Yudel for

every mistake they made, suffering his constant spitting. It was a miracle if they learned to love the holy Torah in spite

of Yudel.

“You know what Yudel the Teacher does if a boy breaks a lantern,” Itzik said. The words ran together, as if he was afraid

he’d be cut off.

Avrum sat down heavily in his chair and stared at the boy with growing alarm.

Itzik angrily snapped at imaginary reins in his hands. “It’s a beating for sure. But then, Jan Nowak came. He brought his

wagon up next to the children. He said, ‘Who’d you steal that lantern from, you dogs? Give it here.’ The little one whose

face I couldn’t see, he had the lantern.” Itzik looked off, as if remembering. “Then Jan stood up and got him with the tail.”

“What tail?”

“The whip.” Itzik’s head dropped. The room was silent except for a clock ticking on the far wall.

“The little one dropped the lantern,” Itzik whispered. “Tzvi tried to get it, but Jan beat him hard. Hard. In the face. All

over. Laughing that laugh he has. You know it. Then Jan’s wife started screaming, ‘Make them hop. Make them dance.’ Jan hollered,

‘Hop, you devils, hop!’ He made those circles on the ground with his whip. When they tried to get out, he lashed them, hard.

There was blood pouring from their faces. The horse was jumping around too, from the sound of the whip and the children.”

Itzik’s jaw quivered.

“I ran to the wagon. I tried to grab his arm to stop him from hitting. I yelled to the kids, ‘Go home.’ Jan said, ‘Who’s jabbering

like a Jew?’ He grabbed the lantern, but the fire went out. I couldn’t see. Jan was whipping and whipping at me in the dark,

but he missed me. I grabbed his wrist to stop him from using the whip. Then his horse bolted, and Jan fell from the wagon.

I put my arms up to break his fall, but I couldn’t. He fell by the wheels. I tried to pull him out in time, but all I got

was a handful of grass.”

Silence again. Avrum’s eyes were bulging. He was figuring what he had to do now. I felt for him. He knew what was what here.

“How bad is Jan?” he said slowly, as if speaking to an idiot.

Itzik paused. “He’s dead. The wagon’s wheel rolled over his head.”

Avrum sat in his chair, dumb with shock; then I could see the terror come to his face. “Does anyone know?”

“His wife. She told them. The Poles already came after me.”

“Where did they come after you?”

“At the cemetery. I hid there, behind Berel Alterman’s wife’s grave.”

“Did they see you?”

“No, something scared them away.”

Some thing? Is he not saying or doesn’t he know about me? And the grass. Was this what he was still holding at my grave, grass from Jan

Nowak? Ptuh! Ptuh! Ptuh! No wonder he kicked it away.

Avrum wasn’t interested in what scared the Poles away from my grave. “What do you want now from me?”

Itzik didn’t answer. The strain of having to ask for anything was all over his face. “My mother, can you make sure nothing

happens to her and the children?” He said it so softly, you could barely hear.

“Wait here,” Avrum said, and left the room.

Shuli looked at Itzik as though it wouldn’t take much for hope to bloom on her face. But he didn’t return her gaze.

“You did a brave thing. It’s a mitzvah, what you did,” she said softly.

He just shook his head.

Avrum returned with his coat and a small money bag. “I’m going for the Russian magistrate. Pray that he’ll send a detachment

of soldiers to keep the peace. God knows what trouble we’ll have now with the Poles for hiding behind Russian skirts.” He

rubbed his forehead worriedly. “I’ll get the droshky. Take this money,” he said. “Give it to your mother. Tell her it’s wages.” Itzik grabbed the pouch and bolted out the door.

SARAH LEIBER’S HOME WAS MORE SHED THAN HOUSE, ONE OF the worst of its kind on that narrow alleyway of mud and stench. Itzik opened the door that hung crooked on its hing

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...