- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

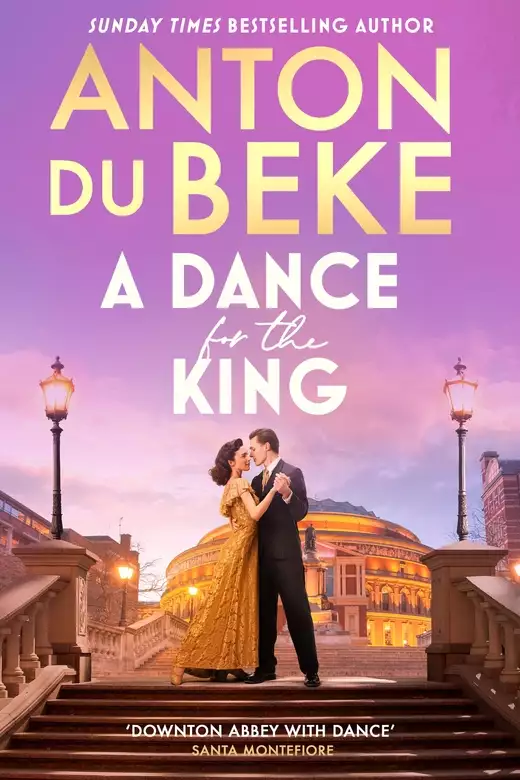

Synopsis

You're invited to a show to remember at the prestigious Buckingham Hotel . . .

In London 1942 the war is far from over for soldier Raymond de Guise. His wife Nancy is overjoyed to be reunited with her husband, and to introduce him to their son. But their safety is threatened once more as Raymond returns to the ballroom at the Buckingham Hotel, ordered to discover the dark secrets held by the glittering high society. On the dancefloor Raymond uncovers a dangerous relationship that could change the course of the war, and also threaten his marriage to Nancy. Can he protect his King and his family before it is too late?

A DANCE FOR THE KING is a pageturning and epic wartime story filled with drama, mystery, dance and romance.

Release date: September 26, 2024

Publisher: Orion

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

A Dance for the King

Anton Du Beke

There it sits, in the very heartland of London: seven storeys of glimmering white, overlooking the verdant oasis of Berkeley Square. Beyond the surrounding townhouses, London is at war. Barrage balloons are strung up in the skies; nightly, the brave boys of the RAF soar across the city, repelling Mr Hitler’s rapacious hordes. On Oxford Street, the grand department store of John Lewis remains in ruins; the craters of Piccadilly are slowly being filled in; rolls of barbed wire and sandbags have turned Horse Guards Parade, and Parliament’s approach, into a military command. London is a city that is brutalised yet defiant, its people crushed but never cowed. From the north to the south, east to the west, London endures …

But here, here in the heart of Mayfair, here sits a fortress defiant.

Come through its doors …

In the ballroom, dancers waltz and turn. On the stage, the Max Allgood Orchestra trumpets out its joyful music, heedless of bombs. In the kitchens, chefs and underlings concoct delights that show no sign of the privation of war. In the rooms and suites, guests are treated as royalty. Indeed, some of them are royalty – for the Buckingham Hotel is a home away from home for the exiled kings, queens and governments of Europe; a shining light of fortitude, a bastion of hope that goodness shall soon win out against all that is wicked in this world.

But come upstairs, into the smoky environs of the Candlelight Club.

Here sit lords and ladies, men of money and men of power; here, glasses are raised and cocktails composed; here, over martinis and Veuve Clicquot, brave men make the decisions that might yet turn the tide of this insufferable war.

You would not think it, not in an establishment as esteemed as this, but someone raising their glass in here tonight is plotting to sell out their king.

Someone toasting their loved ones in here imagines a future where Great Britain has fallen, becoming nothing more than a protectorate of the Reich.

Someone who waltzes in the Grand Ballroom, someone who dines in the Queen Mary Restaurant, someone who walks the halls of this hallowed institution, believes they can bring about the end of this island nation’s valiant fight.

Sometimes, the enemy is not really out there at all.

Sometimes, they’re right here.

Sitting beside you.

Clinking their glasses against your own.

Dancing in your arms …

After a lifetime in the deserts of North Africa, after countless weeks at sea among the invalided and exiled, after the bombs that pulverised the port city of Liverpool where his transport came into dock, Lieutenant Raymond de Guise was grateful to be sitting in a crowded train carriage, surrounded by a hubbub of English voices, making the final approach to the city he loved.

London: the city where it all began.

He hadn’t expected to see it again – not so soon.

There had been plenty of long nights, eking out rations inside the besieged city of Tobruk, when he wondered if he’d see it at all.

If he’d ever lay eyes upon his darling wife, Nancy, or cradle their newborn son in his arms.

And yet here it was, appearing by degrees through the window. For hours now, the train had been grinding through the stations and sidings of London’s approach, stopping and starting again with frightening regularity. More than one train had been derailed in the damage from the Luftwaffe’s bombings last year – nowadays, it was part of the job for the driver and conductors to check the integrity of the tracks up ahead – but Raymond had waited a long year to see Nancy; he could wait a little longer. In his hands were letters she’d sent him along the way. Some had been lost to the oceans, some to the desert sands and the hastened retreats from one billet to the next – but some he’d carried with him across the long arc of the war, and here, right here, was the letter she’d sent when their son Arthur was born. Eight months old, now, and not once in this life had Raymond laid eyes upon him. The boy had taken Raymond’s late brother’s name, but what he smelt like, what he looked like, how he sounded or felt sleeping in his arms, Raymond did not know.

But he was going to find out.

This very day, he was going to find out.

The train juddered to a halt.

Raymond heaved a sigh. Some of the other travellers – none of whom looked as if they’d come as far as Raymond, for this train was filled with office clerks, day-trippers, railwaymen and other city workers – looked exasperated, casting aggrieved glances at the conductor, but Raymond sank instead into his letters. Nancy neither knew nor hoped for his coming. Right now, she was either at home nursing their son – or she was rallying her girls in the housekeeping department at the Buckingham Hotel, that esteemed establishment sitting on London’s Berkeley Square where she and Raymond had first been drawn together. Wherever she was, her day marched obliviously on. The longing, the yearning, was Raymond’s alone.

‘My dearest Raymond,’ Nancy wrote, ‘when Arthur babbles I am sure he is calling for his father. Sometimes, when I sleep, I am calling for his father as well …’

There was commotion further along the carriage now. One of the other passengers seemed to have provoked mirth in a group of city clerks clustered at the end of the carriage. Raymond tried to block out the noise. Here was London, right in front of him. Another half hour, another hour, and he would lay eyes upon her.

He wondered how motherhood had changed her.

He wondered how much a year in the desert had changed him.

He wondered about all the lies he was going to have to tell to explain to her exactly why he had been summoned back to London; exactly why, though his war with a rifle was over, his part in the battle went on.

‘I haven’t heard from you in two long months,’ Nancy had written, ‘but when I sleep, I still feel you beside me. And that is why I know you are out there still. That is why I know, one day, you will be coming back home …’

In her heart, Raymond thought, she had reconciled to not seeing him for years.

But tonight, she would be in his arms.

Moments earlier, further along the carriage, a youth had flurried suddenly out of sleep. He was a young man, nineteen or twenty years old, with coils of black hair and a slightly deranged look in his eyes – and, as he blurted out ‘Where am I?’, splutters of laughter rose up from a group of middle-aged clerks. His reflection in the window glass revealed a man who looked as if he’d spent the night in the back booth of some alehouse, not in a station hotel on the Salisbury plain. He wore a brown suit, which had seen better days, a shirt open at the collar, and carried a trumpet in a beautiful leather case in his hand. But it was not the fact that he was Black that drew the eye – even though he was the only Black man on the train this morning. No, it was his accent, rich and honeyed and dripping with the sounds of his native Chicago, that stirred attention.

‘We’re outside London, sir,’ the conductor said, as he passed. ‘Waiting for an inspection of the tracks up ahead. We’re being held here by the wardens until we can keep going, but it shouldn’t be long.’

The young man shook his head like a dog rising up from the river. ‘About time,’ he cheered, and shook the conductor’s hand so vigorously that the man backed away, unnerved. ‘London’s calling. London at last. London, here I come!’

The group of middle-aged clerks were still staring. The young Black man got to his feet. A more spindly kind of man would be difficult to imagine. Now that he stood, it was obvious his suit was too big for him, and that he still carried with him some of the gangliness of youth. He stood over six feet tall but was thin as a rake. Whistling, he took off along the carriage.

He was loping past the clerks when one of them called out, ‘You’re a Yank, then?’

The Black man inclined his head, his face still split by a dazzling smile. ‘And proud of it!’

‘With the army? I didn’t know you’d landed yet.’

The Black man swivelled on his heel and flashed his smile at every one of the clerks. ‘Gentlemen, I’m a musician, not a fighter. I’m a man of peace … except when I get on that stage!’

He was already sauntering on, eager to be the first off the train and into the wild promise of Paddington Station, when he heard the clerks start snorting. ‘There’ll be more like that coming,’ one of them said. ‘Trust me, we’ll be inundated. A plague like you’ve never seen. I heard, back in America, they’re not allowed to ride the same trains.’

‘It’s a good system. It rather makes sense.’

The young man stopped dead.

His smile died.

His scarecrow body seized up.

‘Oh yeah,’ one of the other clerks snorted, ‘they’ll be sending them over in droves. You think they’ll be letting them have free rein? Or keeping things nice and orderly, like they do back home?’

The young man turned on the spot, marched back towards the clerks, and seethed, ‘What did you say?’

‘That was a private conversation, sir,’ the first clerk said. ‘You’ll be learning some English manners while you’re over here. Eavesdropping is hardly the behaviour of a welcome guest, so if you don’t mind—’

‘Move over,’ the young man said, ‘I want to sit down.’

The clerks looked at him, horrified. ‘There’s not a seat to be spared.’

‘I don’t know, I reckon I could fit. Might even sit on one of your laps, if you’ll have me.’ Without hesitation, he started inveigling his way between two of the clerks.

‘Sir, this is outrageous!’

‘I’ll tell you what’s outrageous,’ the young man snapped, when the clerks – finally finding their brio – jostled him back into the aisle between seats. ‘You think you’re better than me – and there you sit, on your big round backsides, just pouring dirt on others. Yes, sir, they keep my type separate where I come from. Don’t mean it’s right. Don’t mean it’s fair. But look at you, with your ruddy smug faces – you’re closer to pigs than you are good, honest men.’

‘That’s ENOUGH!’

One of the clerks had shot suddenly to his feet. Now he extended a finger and jabbed it at the young man’s breast.

‘You’re a guest in this country, not even a soldier by your own admission, and—’

‘You touch me again,’ snarled the man, ‘and you’ll see what happens.’

It was those words, ‘you’ll see what happens’, that tore Raymond out of the letter he was reading. He’d seen enough fights break out in billets and barracks to develop an instinct for the approaching storm. Nancy’s words – ‘write and tell me you are safe; write something I can read to our son’ – faded out of thought and mind as he folded the letter back into the little leather case where he’d been keeping them, then stood up to see a young Black man puffing out his breast while a portly city clerk jabbed him with a finger.

Each man was appraising the other, daring him to move.

Raymond marched along the carriage until he was almost on top of the altercation.

‘Young man,’ the plump clerk declared, ‘you won’t get far in this country with an attitude like—’

The Black man sighed. ‘I gave you fair warning,’ he said ruefully, then brought back his fist to let it fly.

And he might have done exactly that if only, at that moment, a shadow hadn’t fallen across him, a hand hadn’t clasped his shoulder – and, under the pressure of its fingers, he hadn’t turned round to come face to face with Lieutenant Raymond de Guise.

The young man seemed ready to brawl with Raymond too, but something in Raymond’s demeanour quelled his rage. His ability to calm another man, especially in the theatre of war, was second to no other. It might have seen him become a commander if he hadn’t received that mysterious phone call from the old hotel director, Maynard Charles.

‘We’re almost at London,’ Raymond began, fixing the man’s deep, black eyes with a benign look. ‘Perhaps it would be wiser to just go on your way.’

‘Hear, hear!’ one of the clerks exclaimed. ‘Throw the rabble out. See what a good, upstanding soldier can do, young man?’

Raymond bristled. He could sense the young man bristling too. He’d almost pierced the boy’s outrage and mollified his ire, but suddenly it was erupting again.

There was nothing else for it.

Raymond stepped in front of the young man, making his way into the middle of the altercation.

Then he cast an excoriating eye over the clerks and said, ‘You ought to be ashamed. The boy did nothing to you – nothing but happen by. It’s war, gentlemen – or have you forgotten what that felt like? We’re meant to stick together.’

Taken aback by Raymond’s waspish tone, the clerks slumped into their seats, sharing looks of outrage. Not that Raymond cared; he was already bustling the young man back along the carriage, into the vestibule at its end.

‘You ought to have let me show ’em,’ the young man said. ‘I’ve dealt with sorts like that before. They don’t got any courage, not when it comes down to it. I could have left him on the carriage floor, and no mistake.’

Raymond had to admit that he liked the young man’s bravura. He could have made something of a man like this if he’d been part of the company in Cairo. But it was different back home. Sometimes, being brave was only a whisker away from being foolhardy – and Raymond was quite certain that this young man couldn’t tell one from the other.

‘I think you timed it right. Walking away doesn’t lead to war.’

‘Hey, man, I heard they called that appeasement.’

Then the young man’s face opened in laughter so infectious that Raymond grinned too.

‘The name’s Nelson,’ the younger man said, and grasped the soldier’s arm in a brotherly half-embrace. ‘You look like you been in the wars, sir.’

‘Well I’m home now,’ Raymond replied. ‘I’m Raymond,’ he added, ‘and you’re … a trumpet player?’

Nelson was still swinging the black leather case at his side. ‘I can toot a horn, but it’s not my thing, you know? Problem is, you can’t go carting a grand piano around – so a man’s gotta find himself a second instrument. This here,’ and he hoisted up the trumpet, ‘is on loan from my uncle. Now he can play. You ought to hear him with his trombone. Lucille, he calls it. A man’s gotta have a name for his instrument. It shows he’s in love.’

Nelson was grinning wickedly; it was difficult not to join in.

But the train had started moving at last, and the conductor’s voice hollered up and down the carriage. ‘Next stop, Paddington Station! Paddington Station, coming up!’

‘You want some advice, since you’re coming to London?’ Raymond began. ‘You keep your head down, you stay out of trouble, you work hard – and you walk away from the fights. And, boy, you might just about make it in this city. That is, if the bombs don’t get you first …’

Raymond waited on the platform until Nelson had barrelled away, making certain first that the rabble of city clerks didn’t mean him some further mischief in the station. Then, and only then, did he shoulder his packs and make haste for the station entrance. Outside, the morning was growing old. A throng of passengers just disembarked from their journeys were clamouring for taxicabs lined up by the roadside – but Raymond just hovered at the entrance, took in his first glimpse of London in the January chill, and started to march. After so many weeks of voyaging, he was quite sick of travel – and home was just a short walk away.

Nancy, just a short walk away.

Arthur, waiting for the father he’d never known.

There’d be questions, so many questions, of that there was no doubt. But he’d received his briefing at the Liverpool dock, and there’d already been two weeks of intensive training at a military retreat off the Salisbury Plain – the kind of place that didn’t appear in military manuals, and which didn’t exist in the public record – so at least he felt well prepared. What he didn’t feel prepared for, he realised now, was the rush of feelings that had started coursing through him. When you were away at war, it was easy to enter a strange limbo state – you missed your loved ones, of course, but for a time you existed in a separate world from them, and that made it easier to box your feelings away. Now that he was in London, those rules hardly applied. Nancy was just a quick march away. His son, who knew him by blood but not by body, could be in his arms inside half an hour. His world, changing and then changing all over again.

A voice hailed him from the side of the road.

‘Sir?’

When he looked round, the window of a black taxicab had been wound down and the driver – who looked a cut above the usual London taximan, dressed in a charcoal-grey suit and navy-blue necktie – was piercing him with a look.

‘I’m walking from here,’ Raymond said, his heart filled with imagining that one holy moment when he would step over the threshold at home, that little house in Maida Vale which he and Nancy had made their own.

‘No, Lieutenant, you’re not,’ the driver replied.

He loaded the word ‘Lieutenant’ with such meaning that Raymond immediately understood this was no ordinary taxi driver. Most men might have inferred his rank from the uniform he wore, but there was a knowingness in this man’s eyes, an air of imperial command that did not befit him.

‘Sir, I’m headed home,’ Raymond insisted.

The taximan stepped out of his vehicle, picked his way round and opened up the passenger door. ‘I’ll drop you there myself, but you’ve a little detour first. Step this way, Lieutenant. It would pay to remember: your time isn’t your own; you haven’t been decommissioned, not yet.’

Seeing his family was like a mirage that kept slipping away, the closer he got. He’d known a few mirages like that in the desert. All you could do was steel yourself and accept them for what they were. So it was with a profound sense of resignation that Raymond got into the taxicab and sat there in silence as the driver took him across London, along thoroughfares at once familiar and strange, around the fortified environs of Buckingham Palace, and onto the long boulevard of Piccadilly.

The Buckingham Hotel was only a stone’s throw from here. How strange it would be to see it again.

Yet, the moment he allowed himself to imagine that that was where he was being taken – for wasn’t the Buckingham the very reason he’d been summoned back from Cairo, wasn’t it at the Buckingham Hotel that he was needed the most? – the taxicab pulled into a side street, just beyond the dazzling lights of the Ritz, that fierce rival to the Buckingham Hotel, and the driver shepherded him out.

‘The Deacon Club,’ he announced, approaching a nondescript black door between a leather goods’ shop and a gentlemen’s outfitters. ‘You’ll be attending this place a lot, sir, but mind you don’t mention it to another soul – not even your wife.’

Raymond was already aware there would have to be secrets he kept from Nancy. Such, he was told, was the cost of coming back home and spending the war in her company.

‘Come with me, sir.’

The door to the Deacon Club opened up at the driver’s touch, and Raymond followed him into a narrow hallway, where a concierge waited at a stark desk. This man, with his beak of a nose, did not have the look of a regular butler about him; his eyes told a different story – that lingering under the polite, officious façade was a well-trained, deadly sort of man. He ushered them deeper into the club, and onward Raymond came, up a narrow staircase, along hallways garlanded with portraits of days gone by – until, finally, he was ushered into a dining room with a bar, where gentlemen of dour appearance were taking their meals in abject silence or whispered conversation. Here the butler left them, and the driver – first instructing a waiter to pour Raymond a drink – said, ‘You’ll wait here, Lieutenant, while I make sure your officer is ready.’

It was too early for the whisky they poured him, but its golden hue was so appealing that Raymond allowed himself the indulgence. It slipped down like honey. There were still riches in London, then, even in this age of austerity and rationing.

Some moments later, the driver reappeared.

‘You may come through now, Mr de Guise.’

Beyond the bar was another staircase, and at the top of that another hall. Raymond was ushered through the door at its end, his whisky glass still in hand, and there the driver left him with a final knowing look.

The drawing room he had entered was not so very extraordinary. Dominated by an enormous desk, its walls lined in books – and one particularly savage bear’s head, mounted on dark, stained oak – it smelt of dust, the barbershop scent of Pinaud Clubman, and the smoke from the copious White Owl cigars which appeared to have kept the man he was visiting company through a long night.

There stood Maynard Charles: once the director of the Buckingham Hotel, now an officer with MI5; once, the man who hired Raymond to be a ballroom dancer in the fêted Grand Ballroom, now the man who was about to hire him as a spy.

‘Raymond,’ Maynard intoned, in his deep, plummy voice, ‘welcome to your new war.’

In the Hotel Director’s office, at the end of that warren of passageways behind the check-in desks of the Buckingham Hotel, a man lay dead.

Frank Nettleton – reliable hotel page, stalwart member of the hotel fire watch, sometime ballroom dancer in the glittering environs of the Grand – had only arrived at the office to deliver Mr Knave a note. It was not in the job description for a hotel page, nor a demonstration dancer, to discover dead bodies – particularly when that body had once belonged to the eternal spirit of Walter Knave, the man who had been so calmly navigating the hotel through the choppy waters of war.

The note that Frank had been holding, just a hurried memo from Douglas Guthrie – the Scottish laird currently occupying the Continental Suite – slipped free of Frank’s fingers, then floated like a feather to the floor. ‘Mr Knave?’ Frank whispered, though it was already clear the man was dead. There he lay, in front of the desk that dominated the office, arms and legs splayed out, his face turned to the side and tinged in blue. ‘Mr Knave, can you hear me?’

The note finally touched the carpet at Mr Knave’s side. It had opened up as it fell. There lay the invitation to a dinner Mr Knave would never make. ‘I should be honoured if you were to dine with my wife Susannah and I, at a restaurant of your choosing.’ The venerable guests of the Buckingham Hotel often wanted to curry favour with management – many of these guests came time and time again, and it always reaped dividends to know the hotel director by name – but Walter Knave would not be sending an RSVP.

Frank crouched at his side. The old man had always had pallid features, but not like this. He’d run the hotel in his pomp, steering it through the unprecedented circumstances of the Great War a generation before, and only returned to his post at the outset of this fresh catastrophe.

He reached down to close the man’s eyes. He’d died with them open – but apparently, closing them was more difficult in real life than it was in the pictures. Some sort of rigor must have set in, which meant the poor old man must have met his end the night before.

Frank found a blanket on the armchair by the office fire and covered him gently. He took one last look, then hurried out of the office.

It was difficult to know who to tell. In a daze, Frank picked his way along the long corridor, round the audit office, past the Benefactors Study – and out through the doors that led to reception.

The reception hall of the Buckingham Hotel was buzzing on this early winter morning. He hurried past the ornate marble archway that led into the Grand and straight down the newly restored Housekeeping hall.

He was already at the Housekeeping Lounge, where each morning chambermaids gathered to receive their rotas, when the doors opened. Immediately, the corridor was filled with dozens of chattering chambermaids. A good number of the girls cuffed him around the shoulder and said hello as they passed – for Frank was often to be seen, of an evening, in the chambermaids’ kitchenette, high up in the Buckingham’s rafters, taking tea and toast with the girl he one day intended to marry.

There she was now: Rosa Bright, her heart-shaped face framed by hair as dark as her eyes. He’d been stepping out with her ever since he first came to the Buckingham Hotel, dancing with her in the clubs, sharing stolen moments, dreaming about the life they would one day live together. Rosa was a little older than Frank, though she seemed eternally sixteen – fiery, impassioned, and eager to embark upon every adventure life gave her. Her face lit up upon seeing Frank – ‘I can’t wait for dancing at the Midnight Rooms tonight!’ – but, when Frank did not immediately respond, she clutched his hand and said, ‘Frankie?’ Her accent had softened of late, but there was still the estuary twang of sunny Southend in her voice. ‘Frankie, what happened?’

‘I – I c-can’t say …’

Frank looked to move past, squeezing her hand in reassurance, but Rosa already knew something was dreadfully wrong; Frank had conquered his stammer, but it always crept back in when he was agitated.

‘Is N-Nancy through there?’

Rosa put her arms around him and whispered in his ear, ‘Come and find me later. I’m on the fifth floor.’

He kissed her on the cheek as she drew away, looked back at her as she hurried down the hall – and only then did he bow into the Housekeeping Lounge.

The breakfast things were still laid out across the long wooden table around which the chambermaids gathered each morning. Then he was on the other side of the Lounge, ducking through the doorway into the office.

There sat Nancy, her head in her papers, poring over budgets and rotas – all the manifold tasks that it fell to the Head of Housekeeping to fulfil. Nancy de Guise, née Nettleton, his older sister – and the only maternal figure he’d ever known, for Frank’s mother had died in childbirth, leaving Nancy to bring him up. She was a mother now herself, a working mother no less, and already carried the weight of worlds upon her shoulders – but to Frank she was the only one who would know what to do.

Upon hearing his footsteps, Nancy looked up.

She was more lined of late, weary from work and young motherhood, but immediately she knew something was wrong.

‘Frank, what happened?’

So he told her it all.

Some time later, having shed the weight of responsibility, Frank shivered in the cold out on Berkeley Square, waiting for the black cab to arrive. Standing in Michaelmas Mews, the little alleyway that led from the glorious environs of the square, around the side of the hotel and to the old tradesman’s entrance, he was not as sheltered from the January wind as he would have been if he’d stood beneath the hotel’s grand marble colonnade – but Frank had been drilled in propriety, and knew that a simple hotel page should not be seen where lords and ladies took in their first impressions of the glorious establishment. Consequently, here he waited, in the slush and biting cold, until – what felt like an hour later – a black cab came round the square and parked only feet away from where he stood.

Frank hurried out and opened up the door.

John Hastings – the American industrialist who had become the Buckingham’s principle investor and, last year, the head of the Hotel Board – hardly wanted Frank’s help disembarking, but accepted it all the same. ‘And you’re the one who found him, are you, boy?’

Frank nodded. ‘I went to deliver a note. Lord Guthrie wanted to introduce Mr Knave to his wife at dinner. I hardly thought …’ He swallowed. ‘I’m sorry, sir. I did the best I could. I covered him with blankets and – and – and …’

Mr Hastings, thirty-something and portly, stopped and slapped him on the back. ‘I’m sure you did valiantly, young man, but I’ll take it from here.’

By the time they reached the Hotel Director’s office, it was late morning and the Buckingham was alive. But the news of Mr Knave’s demise had been properly contained – a concierge stood at the door, tasked with sending away any who’d come to see the director. The concierge nodded at Mr Hastings and Frank, then stepped aside to permit them to enter.

Inside, the reverential hush was broken only by the voice of Doctor Evelyn Moore, narrating to Nancy – who stood, a willing doctor’s assistant, against the outer wall, taking notes. The good doctor, who was paid a retainer’s fee by the hotel and attended to its guests’ every ailment, crouched on the floor by the cadaver, taking measurements, making inspections, and thinking out loud. Aside from Nancy and Moore, only two other figures were in attendance: the audit and night managers, the most senior left on site. The secret would have to be revealed – and quickly, before rumour took hold – but at least the narrative might be controlled. That was as important in an establishment like the Buckingham as it was in the halls of Westminster itself.

‘Mr Hastings,’ Doctor Moore began. He was a wispy fellow, towering at more than six and a h

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...