- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

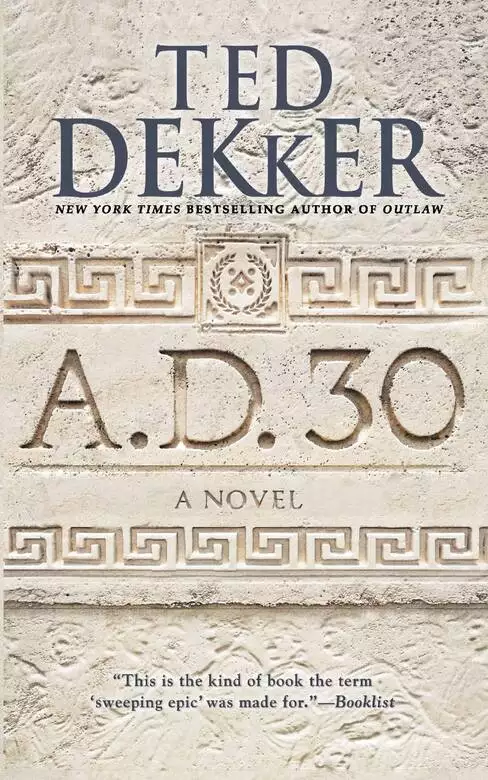

In this historical novel, New York Times bestselling author Ted Dekker tells the epic journey of a woman who rises from the depths of her society to lead her people when she is shown the way by Jesus.

A sweeping epic set in the harsh deserts of Arabia and ancient Palestine.

A war that rages between kingdoms on the earth and in the heart.

The harrowing journey of the woman at the center of it all.

The story of Jesus in a way you have never experienced it.

Step back in time to the year of our Lord, Anno Domini, 30.

Release date: October 28, 2014

Publisher: Center Street

Print pages: 432

Reader says this book is...: emotionally riveting (1) entertaining story (1) historical elements (1) rich setting(s) (1) satisfying ending (1) thought-provoking (1)

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

A.D. 30

Ted Dekker

I stood alone on the stone porch atop the palace Marid, high above the Dumah oasis, as the sun slowly settled behind blood-red sands. My one-year-old son suckled noisily at my breast beneath the white shawl that protected him from the world.

That world was controlled by two kinds: the nomadic peoples known as Bedouin, or Bedu, who roamed the deserts in vast scattered tribes such as the Kalb and the Thamud, and the stationary peoples who lived in large cities and were ruled by kings and emperors. Among these were the Nabataeans, the Jews, the Romans, and the Egyptians.

Two kinds of people, but all lived and died by the same sword.

There was more war than peace throughout the lands, because peace could be had only through oppression or tenuous alliances between tribes and kings, who might become enemies with the shifting of a single wind.

One of those winds was now in the air.

I’d named my son after my father, Rami bin Malik—this before I’d returned to Dumah and become fully aware of the great gulf that separated me from my father. Indeed, the sheikh tolerated my presence only because his wife, Nashquya, had persuaded him. I might be illegitimate, she’d cleverly argued, but my son was still his grandson. She insisted he take us in.

Nasha was not an ordinary wife easily dismissed, for she was the niece of King Aretas of the Nabataeans, who controlled all desert trade routes. Truly, Father owed his great wealth to his alliance with King Aretas, which was sealed through his marriage to Nasha.

Still, I remained a symbol of terrible shame to him. If not for Nasha’s continued affection for me, he would surely have sent me off into the wasteland to die alone and raised my son as his own.

Nasha alone was our savior. She alone loved me.

And now Nasha lay near death in her chambers two levels below the high porch where I stood.

I had been prohibited from seeing her since she’d taken ill, but I could no longer practice restraint. As soon as my son fed and fell asleep, I would lay him in our room and make my way unseen to Nasha’s chambers.

Before me lay the springs and pools of Dumah, which gave life to thousands of date palms stretching along the wadi, a full hour’s walk in length and half as far in breadth. Olive trees too, though far fewer in number. The oasis contained groves of pomegranate shrubs and apple, almond, and lemon trees, many of which had been introduced to the desert by the Nabataeans.

What Dumah did not grow, the caravans provided. Frankincense and myrrh, as valuable as gold to the Egyptians and Romans, who used the sacred incenses to accompany their dead into the afterlife. From India and the Gulf of Persia: rich spices, brilliantly colored cloths and wares. From Mesopotamia: wheat and millet and barley and horses.

All these treasures were carried through the Arabian sands along three trade routes, one of which passed through Dumah at the center of the vast northern desert. Some said that without the waters found in Dumah, Arabia would be half of what it was.

The oasis was indeed the ornament of the deep desert. Dumah was heavy with wealth from a sizable tax levied by my father’s tribe, the Banu Kalb. The caravans came often, sometimes more than a thousand camels long, bearing more riches than the people of any other Bedu tribe might lay eyes on during the full length of their lives.

So much affluence, so much glory, so much honor. And I, the only dark blot in my father’s empire. I was bound by disgrace, and a part of me hated him for it.

Little Rami fussed, hungry for more milk, and I lifted my white shawl to reveal his tender face and eyes, wide with innocence and wonder. His appetite had grown as quickly as his tangled black hair, uncut since birth.

I shifted him to my left, pulled aside my robe, and let him suckle as I lifted my eyes.

As a slave groomed for high service in a Roman house I had been educated, mostly in the ways of language, because the Romans had an appetite for distant lands. By the time I had my first blood, I could speak Arabic, the language of the deep desert; Aramaic, the trade language of Nabataeans and the common language in Palestine; Latin, the language of the Romans; and Greek, commonly spoken in Egypt.

And yet these languages were bitter herbs on my tongue, for even my education displeased my father.

I scanned the horizon. Only three days ago the barren dunes just beyond the oasis had been covered in black tents. The Dumah fair had drawn many thousands of Kalb and Tayy and Asad—all tribes in confederation with my father. A week of great celebration and trading had filled their bellies and laden their camels with enough wares to satisfy them for months to come. They were all gone now, and Dumah was nearly deserted, a town of stray camels that grazed lazily or slept in the sun.

To the south lay the forbidding Nafud desert, reserved for those Bedu who wished to tempt fate.

A day’s ride to the east lay Sakakah, the stronghold of the Thamud tribe, which had long been our bitter enemy. The Thamud vultures refrained from descending on Dumah only for fear of King Aretas, Nasha’s uncle, who was allied with my father and whose army was vast. Though both the Thamud and Kalb tribes were powerful, neither could hold this oasis without Aretas’s support.

But my father’s alliance with Aretas was sealed by Nasha’s life.

In turn, Nasha alone offered me mercy and life.

And Nasha was now close to death.

These thoughts so distracted me that I failed to notice that little Rami’s suckling had ceased. He breathed in sleep, oblivious to the concern whispering through me.

It was time. If I was discovered with Nasha, my father might become enraged and claim I had visited dishonor on his wife by entering her chamber. And yet I could not stay away from her any longer. I must go while Rami was still offering prayers at the shrine of the moon god, Wadd.

Holding my son close, I quickly descended three flights of steps and made my way, barefooted, to my room at the back of the palace, careful that none of the servants noticed my passing. The fortress was entombed in silence.

Leaving my son to sleep on the mat, I eased the door shut, grabbed my flowing gown with one hand so that I could move uninhibited, and ran through the lower passage. Up one flight of steps and down the hall leading to the palace’s southern side.

“Maviah?”

Catching my breath, I spun back to see Falak, Nasha’s well-fed servant, standing at the door that led into the cooking chamber.

“Where do you rush off to?” she asked with scorn, for even the servants were superior to me.

I recovered quickly. “Have you seen my father?”

She regarded me with suspicion. “Where he’s gone is none of your concern.”

“Do you know when he returns?”

“What do you care?” Her eyes glanced over my gown, a simple white cotton dress fitting of commoners, not the richly colored silk worn by those of high standing in the Marid. “Where is the child?”

“He sleeps.” I released my gown and settled, as if at a loss.

“Alone?” she demanded.

“I wish to ask my father if I might offer prayers for Nasha,” I said.

“And what good are your prayers in these matters? Do not insult him with this request.”

“I only thought—”

“The gods do not listen to whores!”

Her tone was cruel, which was not her normal way. She was only fearful of her own future should her mistress, Nasha, not recover.

“Even a whore may love Nashquya,” I said with care. “And even Nashquya may love a whore. But I am not a whore, Falak. I am the mother of my father’s grandson.”

“Then go to your son’s side where you belong.”

I could have said more, but I wanted no suspicion.

I dipped my head in respect. “When you next see Nashquya, will you tell her that the one whom she loves offers prayers for her?”

Falak hesitated, then spoke with more kindness. “She’s with the priest now. I will tell her. See to your child.”

Then she vanished back into the cooking chamber.

I immediately turned and hurried down the hall, around the corner, past the chamber of audience where my father accepted visitors from the clans, then down another flight of steps to the master chamber in which Nasha kept herself.

She was with a priest, Falak had said. So I slipped into the adjoining bathing room and parted the heavy curtain just wide enough to see into Nasha’s chamber.

I was unprepared for what greeted my eyes. Her bed was on a raised stone slab unlike those of the Bedu, who prefer rugs and skins on the floor. A mattress of woven date palms wrapped in fine purple linens covered the stone. This bedding was lined at the head and the far side with red and golden pillows fringed in black, for she was Nabataean and accustomed to luxury. Nasha was lying back against the pillows, face pale as though washed in ash, eyelids barely parted. She wore only a thin linen gown, which clung to her skin, wet with sweat.

One of the seers of the moon god Wadd, draped in a long white robe hemmed in blue fringe, faced her at the foot of the bed. He waved a large hand with long fingernails over a small iron bowl of burning incense as he muttered prayers in a bid to beg mercy from Dumah’s god. His eyes were not diverted from his task, so lost was he in his incantations.

Nasha’s eyes opened wide and I knew that she’d seen me. My breath caught in my throat, for if the priest also saw me, he would report to my father.

Nasha was within her wits enough to shift her eyes to the priest and feebly lift her arm.

“Leave me,” she said thinly.

His song faltered and he stared at her as though she had stripped him of his robe.

Nasha pointed at the door. “Leave me.”

“I don’t understand.” He looked at the door, confounded. “I… the sheikh called for me to resurrect his wife.”

“And does she appear resurrected to you?”

“But of course not. The god of Dumah is only just hearing my prayers and awakening from his sleep. I cannot possibly leave while in his audience.”

“How long have you been praying?”

“Since the sun was high.”

“If it takes you so long to awaken your god, I would require a different priest and a new god.”

Such as Al-Uzza, the Nabataean goddess to whom Nasha prayed, I thought. Al-Uzza might not sleep so deeply as Wadd, but I had never known any god to pay much attention to mortals, no matter how well plied.

“The sheikh commanded me!” the priest said.

“And now Nashquya, niece of the Nabataean king, Aretas, commands you,” she rasped. “You are alone with another man’s wife who has requested that you leave. Return to your shrine and retain your honor.”

His face paled at the insinuation. Setting his jaw, he offered Nasha a dark scowl, spit in disgust, and left the chamber in long, indignant strides.

The moment the door closed, I rushed in, aware that the priest’s report might hasten Rami’s return.

“Nasha!” I hurried to her bed and dropped to my knees. Taking her hand I kissed it, surprised by the heat in her flesh. “Nasha… I’m so sorry. I was forbidden to come but I could not stay away.”

“Maviah.” She smiled. “The gods have answered my dying request.”

She was speaking out of her fever.

I hurried to a bowl along the wall, dipped a cloth into the cool water, quickly wrung it out, and settled to my knees beside Nasha’s bed once again.

She offered an appreciative look as I wiped the sweat from her brow. She was burning up from the inside. They called it the black fever.

“You are strong, Nasha,” I said. “The fever will pass.”

“It has been two days…”

“I could have taken care of you!” I said. “Why must I be kept from you?”

“Maviah. Sweet Maviah. Always so passionate. So eager to serve. If you had not been a slave, you would have been a true queen.”

“Save your strength,” I scolded. She was the only one with whom I could speak so easily. “You must sleep. When did you last take the powder of the ghada fruit? Have they given you the Persian herbs?”

“Yes… yes, yes. But it hardly matters now, Maviah. It’s taking me.”

“Don’t speak such things!”

“It’s taking me and I’ve made my peace with the gods. I’m an old woman…”

“How can you say that? You’re still young.”

“I’m twenty years past you and now ready to meet my end.”

She was smiling but I wondered if her mind was already going.

“Rami has gone to the shrine of Wadd to offer the blood of a goat,” she said. “Then all the gods will be appeased and I will enter the next life in peace. You mustn’t fear for me.”

“No. I won’t allow the gods to take you so soon. I couldn’t bear to live without you!”

Her face softened at my words, her eyes searching my own. “You’re my only sister, Maviah.” I wasn’t her sister by blood, but we shared a bond as if it were so.

Worry began to overtake her face. A tear slipped from the corner of her eye. “I’m hardly a woman, Maviah,” she said, voice now strained.

“Don’t be absurd…”

“I cannot bear a son.”

“But you have Maliku.”

“Maliku is a tyrant!”

Rami’s son by his first wife had been only a small boy when Nasha came to Dumah to seal Rami’s alliance with the Nabataean kingdom through marriage. My elder by two years, Maliku expected to inherit our father’s full authority among the Kalb, though I was sure Rami did not trust him.

“Hush,” I whispered, glancing at the door. “You’re speaking out of fever!” And yet I too despised Maliku. Perhaps as much as he despised me, for he had no love to give except that which earned him position, power, or possession.

“I’m dying, Maviah.”

“You won’t die, Nasha.” I clung to her hand. “I will pray to Al-Uzza. I will pray to Isis.”

In Egypt I had learned to pray to the goddess Isis, who is called Al-Uzza among the Nabataeans, for they believe she is the protector of children, friend of slaves and the downtrodden—the highest goddess. And yet I was already convinced that even she, who had once favored me in Egypt, had either turned her back on me or grown deaf. Or perhaps she was only a fanciful creation of men to intoxicate shamed women.

“The gods have already heard my final request by bringing my sister to my side,” she said.

“Stop!” I said. “Your fever is speaking. You are queen of this desert, wife of the sheikh, who commands a hundred thousand camels and rules all the Kalb who look toward Dumah!”

“I am weak and eaten with worms.”

“You are in the line of Aretas, whose wealth is coveted by all of Rome and Palestine and Egypt and Arabia. You are Nashquya, forever my queen!”

At this, Nasha’s face went flat and she stared at me with grave resolve. When she finally spoke, her voice was contained.

“No, Maviah. It is you who will one day rule this vast kingdom at the behest of the heavens. It is written already.”

She was mad with illness, and her shift in disposition frightened me.

“I saw it when you first came to us,” she said. “There isn’t a woman in all of Arabia save the queens of old who carries herself like you. None so beautiful as you. None so commanding of life.”

What could I say to her rambling? She couldn’t know that her words mocked me, a woman drowning in the blood of dishonor.

“You must rest,” I managed.

But she only tightened her grasp on my arm.

“Take your son away, Maviah! Flee with him before the Nabataeans dash his head on the rocks. Flee Dumah and save your son.”

“My son is Rami’s son!” I jerked my arm away, horrified by her words. “My son is safe with my father!”

“Your father’s alliance with the Nabataeans is bound by my life,” she said. “I am under Rami’s care. Do you think King Aretas will only shrug if I die? Rami has defiled the gods.”

“He’s offended which god?”

“Am I a god to know? But I would not be ill if he had not.” So it was said—the gods made their displeasure known. “Aretas will show his outrage for all to see, so that his image remains unshakable before all people.”

“A hundred thousand Kalb serve Rami,” I said, desperate to denounce her fear, for it was also my own.

“Only because of his alliance with Aretas,” she said plainly. “If I die and Aretas withdraws his support, I fear for Rami.”

Any honor that I might wrestle from this life came only from my father, the greatest of all sheikhs, who could never fail. My only purpose was to win his approval by honoring him—this was the way of all Bedu daughters. If his power in the desert was compromised, I would become worthless.

“He has deserted the old ways,” Nasha whispered. “He’s not as strong as he once was.”

The Bedu are a nomadic people, masters of the desert, free to couch camel and tent in any quarter or grazing land. They are subject to none but other Bedu who might desire the same lands. It has always been so, since before the time of Abraham and his son Ishmael, the ancient father of the Bedu in northern Arabia.

In the true Bedu mind, a stationary life marks the end of the Bedu way. Mobility is essential to survival in such a vast wasteland. Indeed, among many tribes, the mere building of any permanent structure is punishable by death.

In taking control of Dumah, a city built of squared stone walls and edifices such as the palace Marid, a fortress unto itself, Rami and his subjects had undermined the sacred Bedu way, though the wealth brought by this indiscretion blinded most men.

I knew as much, but hearing Nasha’s conviction, fear welled up within me. I wiped her forehead with the cool cloth again.

“Rest now. You must sleep.”

Nasha sagged into the pillows and closed her eyes. “Pray to Al-Uzza,” she whispered after a moment. “Pray to Dushares. Pray to Al-Lat. Pray to yourself to save us all.”

And then she stilled, breathing deeply.

“Nasha?”

She made no response. I drew loose strands of hair from her face.

“Nasha, dear Nasha, I will pray,” I whispered.

She lay unmoving, perhaps asleep.

“I swear I will pray.”

“Maviah,” she whispered.

I stared at her face, ashen but at peace.

“Nasha?”

And then she whispered again.

“Maviah…”

They were the last words I would hear Nashquya of the Nabataeans, wife to my father and sister to me, speak in this life.

IT IS SAID among the Bedu that there are ghouls in the desert—shape-shifting demons that assume the guise of creatures, particularly hyenas, and lure unwary travelers into the sands to slay and devour them. Also nasnas, monsters made of half a human head, one leg, and one arm. They hunt people, hopping with great agility. And jinn, some of which are evil spirits, such as marids, who can grant a man’s wishes, yet compel him to do their bidding in devious matters.

It is said that these ghouls and nasnas and jinn prey on the weak, on children, and on women who are dishonorable. Although I wasn’t sure that such creatures truly existed, I sometimes dreamed of them and woke in fear.

The night Nasha left me I dreamed that I was alone with little Rami, wandering in the wastelands of the Nafud, that merciless desert south of Dumah. We were outcasts and without a kingdom to save us, and the gods were too far above in the heavens to hear our cries. Soon our own wailing was overcome by the mocking cry of ghouls hunting us, and it was with these howls in my ear that I awoke, wet with sweat.

It took only a moment to realize that the ghastly wail issued from the halls and not from the spirits of my dreams.

Little Rami slept soundly on the mat next to me, his arms resting above his shaggy head, lost to the world and the sounds of agony.

I sat up, heart pounding, and knew I was hearing my father from a distant room.

I rolled away from my child, sprang to my feet, and raced up the steps and down the hallway, uncaring that I wasn’t properly dressed, for it was too hot to sleep in more than a thin gown.

So distraught was I that I flung the door open without thought of seeking permission to enter.

My gaze went straight to the bed. Nasha lay on her back with her eyes closed and her mouth parted. Her lips had the pallor of burnt myrrh, gray and lifeless. No breath entered her.

My father, unaware of my entry, stood beside the bed with his back to me.

Here was the most powerful Bedu in northern Arabia, for his strength in battle and raids was feared by all tribes. Like all great Bedu he was steeped in honor, which he would defend to the death. Nasha was responsible for a significant portion of that honor.

His first wife, Durrah, who was Maliku’s mother, had been killed in a raid many years earlier. Filled with fury and thirsty for revenge, Rami had crossed the desert alone, walked into the main encampment of the Tayy tribe, and slaughtered their sheikh with a broadsword right before the eyes of the clansmen. So ruthless and bold was his revenge that the Tayy honored him with a hundred camels in addition to the life of their sheikh, of which Rami had been deserving.

Blood was always repaid by blood. An eye for an eye. Clansman for clansman. Only vengeance could restore honor. This or blood money. Or, less commonly, mercy, offered also with blood in a tradition called the Light of Blood.

It was the way of the Bedu. It was the way of the gods. It was the way of my father.

But here in Nasha’s chamber there was no sign of that man.

Rami was dressed only in his long nightshirt, hands tearing at his hair as he sobbed. He raised clenched fists at the ceiling.

“Why?” he demanded.

Tears sprang to my eyes and I wanted to join him in grief, but I could not move, much less raise Nasha from the dead.

He hurled his accusations at the heavens. “Why have you cursed me with this death? I am a beast hunted by the gods for bringing this curse to the sands. I am at the mercy of their vengeance for all of my sins!”

He was heaping shame on himself for allowing Nasha to die in his care.

“You have cursed me with a thousand curses and trampled my heart with the hooves of a hundred thousand camels!”

He grabbed his shirt with both hands and tore it to expose his chest. “I, Rami bin Malik, who wanted only to live in honor, am cursed!”

I was torn between anguish at Nasha’s passing and fear of Rami’s rage.

“Why?” he roared.

“Father…”

He spun to me, face wet with tears. For a moment he looked lost, and then rage darkened his eyes.

“She’s dead!” His trembling finger stretched toward me. “You have killed her!”

“No!” Had he heard of my visit? Surely not.

“You and the whore who was your mother! And Aretas! And all of this cursed desert!”

I could not speak.

He shoved his hand toward Nasha’s body. “Her gods have conspired to ruin me. I curse them all. I curse Dushares and Al-Uzza. I spit on Quam. All have brought me calamity.”

“No, Father… please… I serve you first, before all the gods.”

He stared at me, raging. “Six months! You have been here only six months and already the gods punish me.”

“She was a sister to me!” I said. “I too loved Nasha…”

“Nasha?” His face twisted with rage. “Nasha bewitched me in pleading I take you in. Today I curse Nasha and I curse the daughter who is not my own. Do you know what you have done?”

I was too numb to fully accept the depth of his bitterness. He mourned the threat to his power, not Nasha’s passing?

“Aretas will now betray me. All that I have achieved is now in jeopardy for the pity I have taken on the shamed.”

And so he made it clear. My fear gave way to welling anger and I lost my good sense.

“How dare you?” I did not stop myself. “Your wife lies dead behind you and you think only of your own neck? What kind of honor lies in the chest of a king such as you? It was you who planted your seed in my mother’s womb! I am the fruit of your lust! And now you curse me?”

My words might have been made of stone, for he stood as if struck.

“And you would rule the desert?” I demanded. “Shame on you!”

My father was no king, for no Bedu would submit to a king. Yet by cunning and shrewdness, by noble blood and appointment of the tribal elders, he was as powerful as any king and ruled a kingdom marked not by lines in the sand, but by loyalty of the heart.

His silence emboldened me. “Rami thinks only of his loss. I see Maliku in you.”

“Maliku?”

“Is he not your true son? Is not my son only a bastard in your eyes?”

“Silence!” he thundered.

But I had robbed the worst of his anger. Misery swallowed him as he stared at me.

He staggered to the bed, sank to his knees, and lifted his face to the ceiling, sobbing. I stood behind, my anger gone, cheeks wet with tears.

Slowly his chin came down and he bowed his head, rocking over Nasha’s corpse.

“Father…”

“Leave me now.”

“But I—”

“Leave me!”

Choked with emotion, I took one last look at Nasha’s stiffening form, then rose and walked away. But before I could leave, the door swung open. There in its frame stood Maliku, Rami’s son.

Fear cut through my heart.

Even so early in the day, he was dressed in rich blue with a black headdress, always eager to display his pride and wealth. He had Rami’s face, but he was leaner and his lips thinner over a sparse beard. His eyes were as dark as Rami’s, but I imagined them to be empty wells, offering no life to the thirsty.

He looked past me and studied Nasha’s still form. I saw no regret on his face, only a hint of smug satisfaction.

Maliku’s stare shifted from Nasha and found me. In a sudden show of indignation, his arm lashed out like a viper’s strike. The back of his hand landed a stinging blow to my cheek.

I staggered, biting back the pain.

His lips curled. “This is your doing.”

Neither I nor my father protested his show of disfavor.

“Take your bastard son and offer yourself to the desert,” he said, stepping past me to address our father. “She must leave us. We must place blame for all to see.”

Father pushed himself to his feet, making no haste to respond. Instead, as a man gazing into the abyss of his doom, he stared at Nasha’s body. Maliku was within his rights. But surely he saw my son as a threat to his power, I thought. This was the root of his bitterness.

“Father—”

“Be quiet, Maliku,” Rami said, turning a glare to his son. “Remember whom you speak to!”

Maliku glared, then dipped his head in respect.

Rami paced, gathering his resolve. If Maliku had been younger my father might have punished him outright for his tone, but already Maliku was powerful in the eyes of many. Truly, Rami courted an enemy in his own home.

“Father, if it please you,” Maliku said, growing impatient. “I only say…”

“We will honor Nashquya at the shrine today,” Rami said, cutting him short. “In private. No one must know she has passed. We cannot risk the Thamud learning of this. They are far too eager to challenge me.”

“Indeed.”

“Then you will take ten men, only the most trusted. Seek out the clans west, south, and north. Tell them to return to Dumah immediately. I would have them here in three days.”

I could see Maliku’s mind turning behind his black eyes.

“Three days have passed since they left the great fair,” he said. “It will take more than three days to reach them and return.”

“Do I not know my own desert? It’s our good fortune that many of our tribe are still so close. They will be traveling slowly, fat from the feasts. Take the fastest camels. Let them die reaching the clans if you must. Leave the women and the children in the desert. Return to me in three days’ time with all of the men.”

Father was right. Ordinarily the Kalb would have been spread over a vast desert, each clan to its own grazing lands.

“If it please you, Father, may I ask what is your purpose in this?”

Rami pulled at his beard. “I would have all of the Kalb in Dumah to pay their respects and mourn the passing of their queen.”

“Their queen? The Bedu serve no queen.”

“Today they serve a queen!” Rami thundered, stepping toward Maliku. “Her name is Nashquya and her husband is their sheikh and this is his will!”

“They are Bedu—”

“She is your mother! Have you no heart?”

Maliku’s face darkened.

“I would have my Kalb in Dumah!” Rami said. “To honor my wife!”

Rami stared at Maliku, then turned and walked to the window overlooking Dumah. When he spoke his voice was resolute.

“Bring me all of that might. Bring me twenty thousand Kalb. Bring every man who would save the Kalb from the Thamud jackals who circle to cut me down.”

“You are most wise.” Maliku paused, then glanced at me. “I would only suggest that she too be sent away.”

“You will tell me how to command my daughter?”

Maliku hesitated. “No.”

A moment of laden silence passed between them.

“Leave me,” Rami said.

We both turned to go.

“Not you, Maviah.”

I remained, confused. Maliku cast me a glare, then left the room, not bothering to close the door.

Rami, heavy with thought, turned away from the window. His world had changed this day, in more ways than I could appreciate, surely.

When he finally faced me, his jaw was fixed.

“I see in Maliku a thirst only for power. Jealousy, not nobility, st

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...