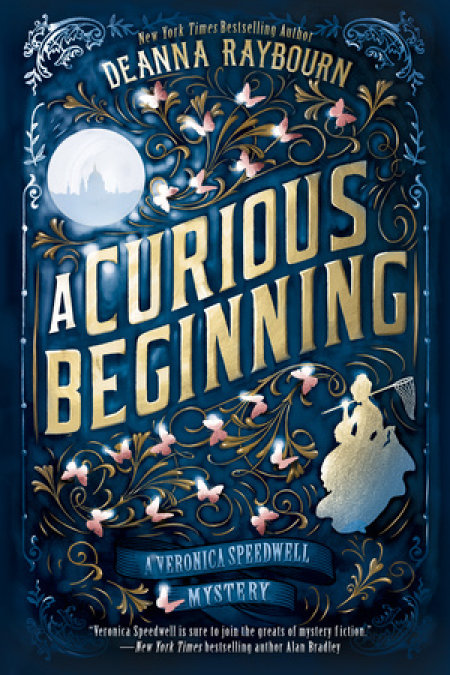

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

London, 1887. As the city prepares to celebrate Queen Victoria's golden jubilee, Veronica Speedwell is marking a milestone of her own. After burying her spinster aunt, the orphaned Veronica is free to resume her world travels in pursuit of scientific inquiry - and the occasional romantic dalliance. As familiar with hunting butterflies as she is fending off admirers, Veronica wields her butterfly net and a sharpened hatpin with equal aplomb, and with her last connection to England now gone, she intends to embark upon the journey of a lifetime.

But fate has other plans, as Veronica discovers when she thwarts her own abduction with the help of an enigmatic German baron with ties to her mysterious past. Promising to reveal in time what he knows of the plot against her, the baron offers her temporary sanctuary in the care of his friend Stoker - a reclusive natural historian as intriguing as he is bad-tempered. But before the baron can deliver on his tantalizing vow to reveal the secrets he has concealed for decades, he is found murdered. Suddenly Veronica and Stoker are forced to go on the run from an elusive assailant, wary partners in search of the villainous truth.

Release date: September 1, 2015

Publisher: Berkley

Print pages: 352

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

A Curious Beginning

Deanna Raybourn

CHAPTER ONE

JUNE 1887

I stared down into the open grave and wished that I could summon a tear. Violent weeping would have been in exceedingly poor taste, but Miss Nell Harbottle had been my guardian for the whole of my life, and a tear or two would have been a nice gesture of respect. The vicar murmured the appropriate prayers, his voice pleasantly mellow, his tongue catching softly on each s. It was the first time I had noticed the lisp, and I only hoped Aunt Nell would not mind. She had been quite exacting about some things, and elocution was one of them. I slipped my dry handkerchief into my pocket with a sigh. Aunt Nell’s death had been neither sudden nor unexpected, and the warmth of our affection had been tepid at best. That her death removed my last attachment to childhood did not unduly alarm me as I stood in the quiet churchyard of Little Byfield. In fact, I was aware of a somewhat disconcerting feeling of euphoria rising within me.

As if to match my mood, the breeze rose a little, and on it fluttered a pair of pale wings edged and spotted with black. “Pieris brassicae,” I murmured to myself. A Large Garden White butterfly, common as grass, but pretty nonetheless. She darted off in search of an early cabbage or perhaps a tasty nasturtium, free as the wind itself. I knew precisely how she felt. Aunt Nell had been the final knotted obligation tying me to England, and I was unfettered once and for all, able to make my way in the world as I chose.

The vicar concluded his prayers and gestured to me. I stepped forward, gathering a clump of earth into my gloved palm. It was good earth, rich and dark and crumbling.

“Rather a waste,” I murmured. “It would make for an excellent garden.” But of course it was a garden, I realized as my gaze swept over the gravestones arranged in neatly serried rows—a garden of the dead, the inhabitants planted to slumber peacefully until they were called to rise by the trumpet of the Lord. Or so the vicar promised them. It seemed a singularly messy undertaking to me. To begin with, wouldn’t the newly risen be frightfully loamy? Shaking off the fanciful thought, I stepped forward and dropped the earth. It struck the lid of the coffin with a hollow thud of finality, and I brushed off my gloves.

There was a touch at my elbow. “My dear Miss Speedwell,” the vicar said, drawing me gently away. “Mrs. Clutterthorpe and I would be very pleased if you would come to the vicarage and take some refreshment.” He smiled kindly. “I know you did not wish for any formal gathering, but perhaps a cup of tea to warm you? The wind is brisk today.”

I had small wish to take tea with the vicar and his dull wife, but accepting was easier than thinking of a reason to refuse.

The vicar led me through the lych-gate and onto the path that led to the great, shambling rectory. He was burbling on like a talkative brook, no doubt reciting from a lesson he had been taught in seminary—“Comforting Thoughts for the Newly Bereaved,” perhaps. I gave him a polite half smile to indicate I was listening and carried on with my thoughts. Whatever they might have been, they were diverted instantly by the curious sensation that we were being watched. I turned to look behind and saw a figure at the lych-gate, tall and beautifully erect, with the sort of posture a gentleman acquires through either generations of aristocratic breeding or enthusiastic beatings at excellent schools. There was something foreign about his mustaches, for they were exuberant, long and sharply waxed into elegant loops, and even at a distance I could detect the slender slashes of old scars upon his left cheek. A German, then, I decided. Or perhaps Austrian. Such scars were unique to the Teutons and their bloodthirsty habit of marking each other with saber tips for sport. But what business did a Continental aristocrat have that required him to lurk near the graveyard of so nondescript a village as Little Byfield?

I turned to put the question to the vicar, but as I did, I saw a flicker of movement and realized our visitor had slipped away. I thought no more about him, and in a very short time I was seated in the stuffy drawing room of the vicarage, holding a cup of tea and a plate of sandwiches. With the effort of packing up the cottage, I had not always remembered to eat in the hours following Aunt Nell’s death. I diligently applied myself to two plates of sandwiches and one of cake, for the vicarage employed an excellent cook.

The vicaress raised her brows slightly at my prodigious appetite. “I am glad you feel quite up to taking some nourishment, Miss Speedwell.”

I did not reply. My mouth was full of Victoria sponge, but even if it had not been, there seemed no polite response. The vicar and his wife exchanged glances, significant ones, and the vicar cleared his throat.

“My dear Miss Speedwell, Mrs. Clutterthorpe and I naturally take a very keen interest in the welfare of everyone in the village. And while you and your aunt are relative newcomers among us, we are, of course, most eager to offer you whatever assistance we can at this difficult time.”

I took a sip of the tea, pleased to find it scalding hot and properly strong. I abhorred weakness of any kind but most particularly in my tea. But the vicar’s pointed reference to “newcomers” had nettled me. True, Aunt Nell had moved to the little cottage in Little Byfield upon Aunt Lucy’s death only some three years past, but English villages were terminally insular. No matter how many socks she knitted for the poor or how many shillings she collected to repair the church roof, Aunt Nell would always be a “newcomer,” even if she had lived among them for half a century. I felt a flicker of mischief stirring and decided with Aunt Nell gone there was no need to suppress it. “She was not my aunt.”

The vicar blinked. “I beg your pardon.”

“Miss Nell Harbottle was not my aunt. It was a title she claimed for the sake of convenience, but we were not kin. Miss Harbottle and her sister, Miss Lucy Harbottle, took me in and reared me. I was a foundling, orphaned and illegitimate, to be precise.”

The vicaress sat forward in her chair. “My dear, you speak very frankly of such things.”

“Should I not?” I asked as politely as I could manage. “There is no shame in being orphaned, nor in that my parents were unmarried—at least no shame that ought to attach to me. It was an accident of birth and nothing more.”

Another significant exchange of glances between the vicar and his wife, but I pretended not to notice. I realized my views were exceedingly unorthodox in this respect. We had moved from town to town as I grew, and in every village, no matter how peaceful and pretty, there was always someone to wag a tongue and pass a judgment. The fact that my surname was different from my guardians’ had always excited suspicion, and it was never long before I heard the whispers alluding to the sins of the fathers being visited on the children, occasionally from Aunt Nell herself. Aunt Lucy had been my champion. Her warm affection had never wavered, but the constant moves had frayed Aunt Nell’s nerves and soured her temper. She used to watch me as I grew, her expression wary, and in time that wariness deepened to something not unrelated to dislike. With Aunt Lucy watching over me, Aunt Nell seldom dared to give tongue to her feelings, but I understood she was quite put out by my excellent spirits and rude good health. I think she would have found it far more just if I had suffered from a crooked back or spotty complexion to mark me as the product of sin. And yet I knew her resentments stemmed from being excluded, being marked out as a subject of gossip by the very Christian folk into whose bosom she longed to be gathered. Folk like the Clutterthorpes.

“I am afraid we did not have the pleasure of knowing Miss Harbottle’s sister,” the vicar began.

I recognized an inducement to talk when it was offered and swallowed my mouthful of cake to oblige him. “Miss Lucy Harbottle died some three years ago. In Kent—no, I am mistaken,” I said, tipping my head thoughtfully. “It was in Lancashire. That was after we lived in Kent.”

“Indeed? You seem to have lived in very many places,” the vicaress commented, only the slight pursing of her lips suggesting that it might not be in the best of taste to change one’s house almost as often as one changed one’s shoes.

I shrugged. “My guardians did not care to stay long in one place. We moved frequently, and I have been fortunate to live in most corners of this country.”

The pursed lips pushed out a little further. “I cannot like it,” Mrs. Clutterthorpe pronounced roundly. “It is not right to uproot a child in so cavalier a fashion. One must provide a stable home when one is bringing up a young person.” Mrs. Clutterthorpe, who had no children of her own, was given to such pronouncements. She was also very fond of issuing directives on how children ought to be weaned, fed, toileted, and taught their letters. Her husband might have learned to ignore her declarations, but being comparatively new to the village, I had not.

I considered the vicaress with the same detachment I might study a squashed caterpillar. “Really? I found it perfectly ordinary and quite useful,” I said at last.

“Useful?” The vicar’s brows rose quizzically.

“I learned to converse with all sorts of people under many and various circumstances and to depend upon no one but myself for entertainment and support. I gained self-reliance and independence, qualities which I must now rely upon in my present situation.”

His brows relaxed. “Ah, you bring me to the point of this discussion,” he said in some relief.

Before he could continue, the vicaress cut smoothly across him. “My dear, no doubt you will think us meddlesome,” she began, leveling me with a look that dared me to do so, “but the vicar and I are most concerned about your welfare.”

I swallowed the last of the cake and dusted my fingertips of crumbs. “That is very good of you, I am sure, Mrs. Clutterthorpe. But I can assure you I have my welfare entirely in hand.”

Mr. Clutterthorpe looked a trifle startled, but his lady was not so easily cowed. She gave me a thin smile. “I am sure you think so. Young ladies,” she said, with a slight emphasis on the word “young” to show she did not really mean it, “do not always know best. You must permit us to guide you with the benefit of our years and wisdom.”

I glanced at Mr. Clutterthorpe but found no succor there. He had applied himself to a fish-paste sandwich as if it were the most interesting thing he had ever seen. I did not blame him. It seemed to me the shortest way to an easy life for him was by capitulating to his wife at every possible opportunity.

“As I said, Mrs. Clutterthorpe, I have made arrangements.”

The vicar looked up, his expression pleased. “Oh, so you are settled, then? Did you hear, Marjorie? We need not worry about Miss Speedwell,” he finished with a jovial smile directed to his spouse.

Her lips thinned. “Whatever arrangements Miss Speedwell has made, I am sure she will be quick to alter them when she learns of my conversation with Mr. Britten this morning,” she said with an air of satisfaction. “Mr. Britten is a farmer with substantial property, very prosperous,” she told me. “And since the death of poor Mrs. Britten, he is in sore need of a wife for himself and a mother for his little ones. You would be mother of six!”

I tilted my head and regarded her thoughtfully as I considered my reply. In the end, I chose unvarnished truth. “Mrs. Clutterthorpe, I can hardly think of any fate worse than becoming the mother of six. Unless perhaps it were plague, and even then I am persuaded a few disfiguring buboes and possible death would be preferable to motherhood.”

She went white for a moment, then deeply red. In his chair, the vicar was choking gently into a handkerchief, but when I rose to offer assistance, he waved me aside with a genial hand.

Mrs. Clutterthorpe recovered herself, gripping the arms of her chair so tightly I could see the bones of her knuckles through the papery skin. “I have heard you are fond of a jest, and I think it amuses you to shock respectable folk.”

I spread my hands and adopted a disingenuous expression. “Oh no, Mrs. Clutterthorpe. I never mean to shock anyone. It simply happens. I have a dreadful habit of speaking my mind, and it isn’t one I look to curb, so you must see that your suggestion of marriage to this Mr. Britten is quite unsuitable.”

“It is not the suggestion which is unsuitable,” she countered coldly. “I have thus far overlooked the rumors which have come to my ears regarding your behavior whilst abroad, but if you insist upon utter frankness, let us have it.”

I gave her a smile of devastating politeness and answered her in my sweetest tone. “What rumors, Mrs. Clutterthorpe?”

Her high color, almost faded, heightened again, mottling her complexion. She darted a glance at her husband, but he bent swiftly to fuss with his shoe buttons, hiding his face. “A decent lady would not speak of such things,” she replied, clearly relishing the chance to do exactly that.

“But you have introduced them into the conversation,” I pointed out gently. “So let us be candid. What rumors?”

“Very well,” she burst out. “I have it on good authority that during your trip to Sicily you behaved immorally with an American traveler.” She scrutinized me from head to heels, condemnation in her eyes. “Oh yes, Miss Speedwell, we have heard of your indiscretions. You are fortunate that Mr. Britten is willing to overlook such shortcomings in a potential wife.”

I bared my teeth in a wolfish smile. “And who told him of them? Never mind, I think I can guess.” I rose and collected my gloves. The vicar leaped to his feet and I extended my hand. “Thank you for your kindness during my aunt’s illness. I shall not see you again. I am off this very afternoon upon my next adventure.”

He dipped his head conspiratorially. “More butterflies?” he asked.

“What else?”

He shook my hand, but before I could make my escape, Mrs. Clutterthorpe thrust herself to her feet and launched a fresh attack.

“You are a foolish, impetuous person,” she said stoutly. “You cannot mean to go friendless into the world and spurn the prospect of an excellent marriage to a man who will look past the indelible stain of your iniquities.”

“I am quite determined to be mistress of my own fate, Mrs. Clutterthorpe, but I do sympathize with how strange it must sound to you. It is not your fault that you are entirely devoid of imagination. I blame your education.”

Mrs. Clutterthorpe stood with her mouth agape, lips moving silently.

I stepped past her, then turned back as I reached the hall. “Oh, and you might tell your sources—it wasn’t an American in Sicily. It was a Swede. The American was in Costa Rica.”

CHAPTER TWO

As I walked down the path towards Wren Cottage, I found my step was very light indeed. I owed the Clutterthorpes a debt of gratitude, I reflected. I had been feeling a little dull after the long, gloomy months of Aunt Nell’s decline, but the visit at the vicarage had cheered me greatly. I was always on my mettle when someone tried to thwart me—poor old Aunt Nell and Aunt Lucy had learned that through hard experience. I had been an obstinate child and a willful one too, and it did not escape me that it had cost these two spinster ladies a great deal of adjustment to make a place for me in their lives. It was for this reason, as I grew older, that I made every effort to curb my obstinacy and be cheerful and placid with them. And it was for this reason that I eventually made my escape, fleeing England whenever possible for tropical climes where I could indulge my passion for lepidoptery. It was not until my first butterflying expedition at the age of eighteen—a monthlong sojourn in Switzerland—that I discovered men could be just as interesting as moths.

It was perfectly reasonable that I should be curious about them. After all, I had been reared in a household composed exclusively of women. Friendships with the opposite sex were soundly discouraged, and the only men ever to darken our door were those who called in a professional capacity—doctors and vicars wearing rusty black coats and dour expressions. Village boys and strapping blacksmiths were strictly off-limits, and when a splendid specimen presented itself for closer inspection, I behaved as any good student of science would. My first kiss had been bestowed by a shepherd boy in the forest outside Geneva. I had hired him to guide me to an alpine meadow where I could ply my butterfly net to best effect. But while I pursued Polyommatus damon, he pursued me, and it was not long before the diversions of kissing took the place of butterflies. At least for the afternoon. I enjoyed the experience immensely, but I was deeply aware of the troubles I might encounter if I were not very careful indeed. Once back in England, I made a thorough study of my own biology, and—armed with the proper knowledge and precautions and a copy of Ovid’s highly instructive The Art of Love—I enjoyed my second foray into formal lepidoptery and illicit pleasures even more.

Over time, I developed a set of rules from which I never deviated. Although I permitted myself dalliances during my travels, I never engaged in flirtations in England—or with Englishmen. I never permitted any liberties to gentlemen either married or betrothed, and I never corresponded with any of them once I returned home. Foreign bachelors were my trophies, collected for their charm and good looks as well as attentive manners. They were holiday romances, light and insubstantial as thistledown, but satisfying all the same. I enjoyed them enormously whilst abroad, and when I returned from each trip, I was rested and satiated and in excellent spirits. It was a program I would happily have recommended to any spinster of my acquaintance, but I knew too well the futility of it. What was to me nothing more than a bit of healthful exercise and sweet flirtation was the rankest sin to ladies like Mrs. Clutterthorpe, and the world was full of Mrs. Clutterthorpes.

But I would soon be past it all, I thought as I stooped to snap off a small sprig of common broom. Its petals glowed yellow, a cheerful reminder of the long, sunny summer to come—a summer I would not spend in England, I reflected with mingled emotions. At the start of each new journey I felt a pang of homesickness, sharp as a thorn. This trip would take me across the globe to the edge of the Pacific, no doubt for a very long time. I had passed the long, chilly spring months at Aunt Nell’s bedside, spreading mustard plasters and reading aloud from improving novels while I dreamed of hot, steaming island jungles where butterflies as wide as my hand danced overhead.

My daydreams had been a welcome distraction from Aunt Nell’s querulous moods. She had been by turns fretful and sullen, irritated that she was dying and disgusted that she was not quicker about it. The doctor had dosed her heavily with morphia, and she was seldom truly lucid. Many times I had caught her watching me, her lips parted as if to speak, but as soon as I lifted a brow in inquiry, she had snapped her mouth closed and waved me off. It was not until the last fit had come upon her, suddenly and without warning, that she had tried to speak and found she could not. Robbed of speech, she tried to write, but her hand was weak, stiff with the apoplexy that had stilled her tongue, and she died with something unsaid.

“No doubt it was a reminder to pay the milk,” I said, tucking the broom into my buttonhole. But I had seen to the dairy bill as quickly and efficiently as I had done everything these past months. Accounts with the doctor, butcher, and baker had all been settled. The rent on the cottage was paid through the end of the quarter on Midsummer Day. Most of the furnishings had been carted away and sold, leaving the few pieces that had come with the cottage—a couple of chairs, a kitchen table, a grievously worn rug, and a poorly executed still life that looked as if it had been painted by someone with a grudge against fruit. All of the Harbottle personal effects and the last of my carefully mounted butterflies had been sold to fund my next expedition.

All that remained to be done was to take up my small carpetbag and leave the key under the mat, provided I could find the key, of course. Folk in the village were remarkably relaxed about things like keys—and waiting for invitations, I realized as I reached the doorstep. For the cottage door stood ajar, and I had little doubt one of the village matrons had availed herself of my absence to call with a cake or perhaps a meat pie for my supper. Aunt Nell had not been popular enough to warrant attendance at her funeral by the inhabitants of Little Byfield, but an eligible spinster would bring them all out en masse, bearing sponge cakes and consolation—or worse, unattached sons for my perusal. A daughter-in-law with competent nursing skills was a tremendous coup for an elderly widow, I reflected with a shudder. I pushed open the door, prepared to do my duty and offer tea, but the greeting died upon my lips. The front room of the cottage was a ruin, the carpet littered with broken bits from the wreckage of a cane chair. The only painting—the indifferent still life—had been slashed, its frame reduced to splinters, and the cushions of the window seat had been torn open, goose down still floating lazily upon the air.

My gaze fixed upon the drifting feathers and I realized that whoever had done this thing must have done so within the last few minutes. Just then, a slight scraping noise came from the kitchen. I was not alone.

Thoughts winged through my mind almost too quickly to grasp. The open door stood behind me. I had made no noise. Escape would be a simple matter of turning on my heel and slipping silently out the way I had come. Instead, my hand reached out of its own accord to the umbrella stand and took up the sword stick I had purchased in Italy.

My heart surged in anticipation. The sword stick was a sturdy piece, made of good, stout hardwood. I pressed the button, releasing the sheath, and the blade came free with a silky murmur of protest. The edge of the blade was dull, for it had been some years since it had been sharpened or oiled, but I was pleased to see the end was still alarmingly pointed. I must thrust rather than slash, I reminded myself as I crept towards the kitchen.

A flurry of other noises told me that the intruder had not yet fled and, furthermore, had no notion of my presence. I had the element of surprise, and armed with that and my sword, I flung open the door, giving a very good impression of what I imagined a Maori battle scream might sound like.

Instantly, I realized my mistake. The fellow was enormous, and it occurred to me then that I had overlooked the essential precaution of taking the measure of one’s opponent before launching an attack. He was well over six feet in height, and the breadth of his shoulders would have challenged the frame of any door. He wore a tweed cap pulled low over his features, but I discerned a gingery beard and an expression of displeasure at the interruption.

To my surprise, he did not use his size to his advantage to overpower me. Instead he turned to flee, upending the long deal table to throw a barrier between us. The most cautious course of action would of course have been to let him go, but caution held little charm for me. My rage was roused at the sight of the ruined cottage, and without any conscious decision on my part, I gave chase, vaulting over the table and following him down the garden path. His was the advantage of size, but mine was the advantage of terrain; I knew it and he did not. He followed the stone path to the bottom of the garden where the road passed by. I turned hard to the left and made straight for the hedge, plunging into a gap and emerging, breathless and beleafed, just as he passed by. I reached a hand and grasped him by the sleeve, yanking hard.

He whirled, his eyes wide with surprise—and panic. For a heartbeat he hesitated, and I lifted the sword stick.

“What is your business at Wren Cottage?” I demanded.

He darted a glance to the end of the road, where a carriage stood waiting. That glance at the conveyance seemed to decide him. I brandished the sword stick again, but he simply reached out, batting the blade aside with one thick hand while he grabbed my wrist with the other. He gave a sharp twist and I cried out, dropping the stick.

He began to drag me towards the carriage. I dug in my heels, but to no avail. My slender form, though athletic and supple enough for purposes of butterflying, was no match for this fellow’s felonious intent. I lowered my head and applied my teeth to the meatiest part of his hand, just above the seat of the thumb. He howled in pain and rage, shaking his hand hard, but would not loose me. He put his other hand to my throat, tightening his grip as I bore down with my teeth like a terrier upon a rat.

“Unhand her at once!” commanded a voice from behind. I glanced over my shoulder to see the Continental gentleman from the lych-gate. He was older than I had thought; at this distance I could see the lines about his eyes and the heavy creases down each cheek, the left crossed with his dueling scars. But he drew no sword against this miscreant. Instead, he held a revolver in his hand, pointing it directly at the fellow.

“Devil take her!” the intruder growled, shoving me hard away from him and directly into the gentleman’s arms. My newfound champion dropped the revolver to catch me, setting me on my feet again with care.

“Are you quite all right, Miss Speedwell?” the gentleman inquired anxiously.

I made a low sound of impatience as the villain reached the end of the road and vaulted into the waiting carriage. The horses were swiftly whipped up and the carriage sprang into motion as if the very hounds of hell were giving chase. “He is getting away!”

“I think perhaps this is a good thing,” was my companion’s gentle reply as he pocketed his revolver.

I turned to him, noticing for the first time that his brow was bleeding freely. “You are hurt,” I said, nodding towards his head.

He put a tentative finger to the flow, then gave me a quick smile. “I am rather too old to be dashing through hedges,” he said with a rueful compression of the lips. “But I think it is not so serious as my other hurts have been,” he told me, and my gaze flicked to his dueling scars.

“Still, it ought to be cleaned.” I took a handkerchief from my pocket, not one of those ridiculous flimsy scraps carried by fashionable females, but a proper square of good cambric, and pressed it to his face.

I smiled at him. “This was rather more adventure than I had expected in the village of Little Byfield. Thank you for your timely interference, sir. I was prepared to bite him to the bone, but I am glad it proved unnecessary. I did not much care for the taste of him,” I added with a moue of displeasure.

“Miss Veronica Speedwell,” he murmured in a voice thick with the accents of Mitteleuropa.

“I am. I believe you have the advantage of me, sir,” I said.

“Forgive me for the informality of the introduction,” he said. He produced a card. “I am the Baron Maximilian von Stauffenbach.”

The card was heavy in my fingers. It bespoke wealth and good taste, and I ran my thumb over the thickly engraved crest. He clicked his heels together and made a graceful bow.

“I am sorry I cannot offer you a place to sit,” I told him as we made our way into the kitchen. “Nor a cup of tea. As you saw, I seem to have been intruded upon.”

The baron’s eyes sharpened under his slender grey brows as he glanced about the wreckage of the room. “Has anything of importance been taken?”

I moved to the shelf where a tiny tin sewing box shaped like a pig usually stood in pride of place. It had been dashed to the floor and rolled to the corner. I was not surprised the housebreaker had overlooked it. Aunt Lucy had firmly believed in hiding one’s money in plain sight, reasoning that most thieves were men and that a man would never think to look for money in so homely and domestic an

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...