- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

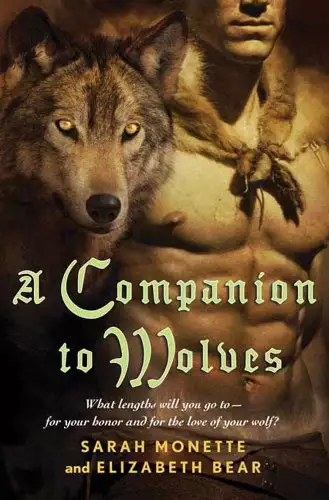

A Companion to Wolves is the story of a young nobleman, Isolfr, who is chosen to become a wolfcarl -- a warrior who is bonded to a fighting wolf.

Isolfr is deeply drawn to the wolves, and though as his father's heir he can refuse the call, he chooses to go. The people of this wintry land depend on the wolfcarls to protect them from the threat of trolls and wyverns, though the supernatural creatures have not come in force for many years. Men are growing too confident. The wolfhealls are small, and the lords give them less respect than in former years.

But the winter of Isolfr's bonding, the trolls come down from the north in far greater numbers than before, and the holding's complaisance gives way to terror in the dark. Isolfr, now bonded to a queen wolf, Viradechtis, must learn where his honor lies, and discover the lengths to which he will to go when it, and love for his wolf, drive him.

At the Publisher's request, this title is being sold without Digital Rights Management Software (DRM) applied.

Release date: July 29, 2008

Publisher: Tom Doherty Associates

Print pages: 304

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

A Companion to Wolves

Elizabeth Bear

ONE

Njall could not stop looking at the wolf.

She lay on the flags before the fire in his father's hall at Nithogsfjoll and panted, despite the chill. Njall was sixteen, almost a man, even if he was hoping for just one more spurt of growth, but her head was as broad as the span of his palm between her eyes. His arms couldn't have circled her barrel, and if she rose on her long racer's legs, she would--almost--be able to look him in the eye, were her attention not reserved entirely for her master.

She was big even for a trellwolf, and more, she looked tired. Her winter coat was shedding in hanks and clumps, like handfuls of dirty rags gray with scrub-water, and he could see her ribs under the skin like sprung staves. Her midsection bulged with the promise of pups, and her heavy black nipples leaked watery fluid on the stones where she lay, infinitely patient, waiting for her master to finish his business with Njall's father.

Njall didn't know what the business was, exactly, but he did know his father wasn't pleased to be doing it. Njall had been exiled--not to the boys' dormitory but to his mother'sempty solar--and fed his noon meal in isolation and bid stay like a puppy. Which he was not, and it rankled. Perhaps it was the insult that sent him, once the ale and bread and cheese and wizened last-winter apple were gone, edging down the long ragged curve of the stair to peer around the corner into the hall, stone rough under his palms, and learn what business his father had that his heir was excluded from.

And perhaps it was curiosity, too, for the men of the wolfheall almost never came to the keep. They were not welcome here, and they knew it.

The wolf had noticed him, for her ears flicked toward him now and again, but she never moved her firelight-hazel eyes from her master's face.

Njall had seen her master before--had even seen her at his side--among the cottages that clustered around the roots of his father's keep like goslings huddled at their mother's feet. The wolfcarl was a big man, almost as tall and stocky as a troll himself, wild-bearded, his graying red hair braided back from his temples; the edge of the axe he carried was bright with nicks and sharpening. He was Hrolleif, the Old Wolf, high-ranked in the werthreat, and Njall knew the villagers--and the manor--owed him obedience and fear.

Obedience, for he and the trellwolves and the werthreat were all that stood between the village and the trolls and wyverns of the North. And fear, for he was of the Wolfmaegth, the Wolf-brethren, and not quite human anymore. The more so because he had bonded a bitch, a Queen-wolf, with all that that implied.

Njall had heard stories about the werthreat and the trellwolves all his life; when he was a little boy, his nurse had threatened him that if he wasn't good, his father would tithe him to the wolfheall. Everyone knew the men of the wolfheall were half-wolf themselves, dark and violent in their passions, that they drank the blood of their fallen enemies and nursed from the teats of their she-wolves. Nodecent man, said Njall's father, wanted anything to do with them.

Njall didn't want anything to do with Hrolleif. He just wanted to look at the wolf.

His father's voice rang across the hall: "And I'm telling you there are no boys of an age to give to your tithe. You won't take them little but you don't want them once they've come to be men, either. We do not have that many children, wolfheofodman, and I cannot conjure them out of the fire for your asking."

"I thought your eldest son was of an age, Lord Gunnarr."

"My son is not for the tithe!"

Njall flinched back at the vehemence in his father's voice, and the wolf's head turned. For a dizzying moment her eyes caught him, pinned him like a spear through the gut, firelight and autumn leaves and a clarity he'd never seen in a dog's eyes, and then she looked back to her master, and Hrolleif laughed.

"Come out, then, pup! Let us see this boy who is not for the tithe."

Njall heard his father curse, and if it had just been Hrolleif he wouldn't have moved. Obedience was owed to his father, as jarl and as sire.

But the wolf had looked at him.

Njall came the rest of the way down the stairs, not looking at his father. Not looking at Hrolleif. He kept his eyes fixed on the trellwolf, and although she did not look at him again, her ears monitored his movements.

"So," said Hrolleif, and Njall had to look at him now, tilting his head to meet the Old Wolf's eyes. "My sister says you might be fit to join our threat, youngling. What think you?"

Sister? Njall was bewildered; the only people in the arched and gloomy hall were his father, Hrolleif, and himself, and why would the wolfheofodman be taking a woman's advice? But then the wolf turned her massive head to give him another look, this merely in passing, not the breath-stealingblow of before, and he knew that Hrolleif had meant her. His sister.

He gulped and said, "I do not know, Lord Hrolleif."

"An honest answer, at least. I do like a boy who doesn't swagger." Hrolleif stepped forward, swiftly and with such power that it took a conscious effort for Njall to hold his ground. He caught Njall's jaw in one broad hand, turning his face toward the firelight. Peeling calluses scratched Njall's face. "Handsome lad. He takes after your lady wife, I see."

"Damn you, Hrolleif--"

"Lord Gunnarr." All the easy amusement was gone from Hrolleif's voice, although his fingers stayed gentle against Njall's face. "You know the laws. You owe the wolfheall tithe, and as you yourself have said, there are not many lads of the right age in manor or village. We cannot farm when we are fighting, and if we are not fighting, you are jarl of--" His free hand rose in an expansive gesture "--nothing."

"Thorkell Blacksmith's son," Njall's father said, and Njall was embarrassed at the note of pleading in his voice.

"Is simpleminded," Hrolleif said flatly. "As this one is not. What's your name, pup?"

"Njall, Lord Hrolleif."

"Njall. You will fulfill your house's duty to the wolfheall, will you not?"

Fear blocked Njall's throat. Wolfheall. There were stories--he turned away, pulling against Hrolleif's grip, so he would not have to look into the wolfheofodman's eyes or at his father's rage. He owed a duty to his father. To the village and the manor. He was the jarl's son, raised to be heir. There was a girl, Alfleda, whom he'd half-promised to take as a paramour once he was married, and there was a betrothal to a jarl's daughter he'd never met, and there was his father's gaze, resting on him now with an iron weight.

And there were the stories of what the men of the wolfheall did with each other, with the boys who went in tithe.

But as he turned, the trellwolf lifted her head again and caught him with a gaze of such piercing, knowing sweetness that he swallowed the fear.

He couldn't stop looking at the wolf.

And he owed a duty to the wolfheall, too.

Because Hrolleif was right; if the wolfheall did not fight, there would be nothing left worth fighting for.

"Yes, Lord Hrolleif," Njall said, and his father the jarl turned away and slammed his fist against one of the great supporting beams.

"All is not lost, Gunnarr," Hrolleif said, releasing Njall and turning to go, his wolf--his sister--coming slowly to her feet to follow him. "He may not be chosen. It is a spring litter, after all, and spring litters are small." He paused, and traded a glance with the wolf. "Send him with the wagon tomorrow, when you deliver the rest of the tithe. I'll not take a boy from his mother without a kiss."

Njall swallowed again as the door closed behind Hrolleif. At another time he might have protested the implication that he was still a child, still tied to the woman's world of kitchen and solar. But now, his hands shook and his knees trembled. The more so when his father, staring at the banded door, did not raise his voice at all but only said, gently, as if to a woman, "Njall."

"Father?"

"I cannot stop you. You've sixteen summers, and were you not to be jarl after me, you'd be a year or three 'prenticed. But think a moment. What if that wench of yours is with child? What of your mother, and your sister, too? If I were lost on the hunt or the field, who would care for them and keep the town strong?"

"Father--" Njall said. His hands clenched in the fabric of his trews. He shook his head, but Gunnarr stayed him with a hand before he could answer, whatever he might have said.

"Think about it," Gunnarr said. "Before you sell yourself to be some ... unclanned bastard's catamite. Or worse." He shook his head, and turned to stare Njall in the face."Go to the dormitory, son. You have until morning to change your mind."

Of course Njall couldn't stay there. At this hour of the day the older boys were all at weapons-practice--as Njall should have been if his father had not chosen to try to hide him away like the child he wasn't--and the younger boys were giggling over some elaborate game among themselves. There was neither comfort nor counsel to be looked for from that quarter. He found himself shivering with delayed reaction, rubbing his hands across his face and then sniffing the fingers as if the smell of Hrolleif's wolf could have somehow transferred from skin to skin. He paced, and threw himself on the bed, and rose to pace again. He sent one of the younger boys to look for Alfleda, but the child returned to say that she had left the keep, and had said to tell Njall that she could not be found.

So was a woman's opinion made plain.

Eventually, inevitably, Njall's pacing led him out of the dormitory, across the courtyard, and up the stair toward his mother's solar. Perhaps he was not thinking clearly, but he had heard what Hrolleif had said--tomorrow, with the rest of the tithe--and, even be it womanish and weak, childish, he did not wish to leave without bidding his mother farewell.

Chosen by a wolf, he thought, and felt again the brush of the trellwolf's amber eyes.

He was halfway up the stairs when he realized that he had seen not a single servant or waiting woman--as if they had all vanished or been sent away--and that the keep, rather than bustling with dinner preparations, was silent as moonset. Hiding from Gunnarr's temper, no doubt; it could be formidable when there was cause. Njall knew the back of his father's hand well enough, although never without reason.

He had hoped that, when his own time came to inherit, he would make such a lord, so just and so strong.

Raised voices paused Njall's footsteps in the antechamber to his mother's domain. He pressed back against a tapestry, breath short, because one of the voices was his father's.

"We must send him away, Halfrid. Send him to the monks at Hergilsberg, away from Nithogsfjoll. Better a monk than a beast."

"Gunnarr." His mother's voice, smooth and level. Njall could picture her, tall and stalwart in her white kirtle and indigo surcote, her hips broad with childbearing and the corners of her eyes crinkled with smiles. It hurt to think of her, of how she smelled of barley-and-mint-water, of her fingers quick with a needle and a silver thimble. "You cannot send him away."

"I'll tell the wolfheofodman he ran."

"And when the wolf-bitch cannot find his trail over new snow? The wolfheall will not protect us if we do not tithe, my husband. As is only just. It is the law. Besides, I do not think you will convince him to flee. He knows his own honor." Gentle, implacable, and Njall felt something uncomfortable twist in his belly.

Perhaps sometimes it was wise to listen to a woman. Not that he would have to learn, unless he wasn't chosen. Wolfcarls did not marry. But for a woman's voice to speak reason when a man's counseled cowardice--there was shame.

"Damn you, Halfrid." But surrender filled Gunnarr's voice, although his next words fell cold as stones. "You know what they do to those boys."

Njall heard footsteps, his father's footsteps; he slid between the tapestry and the wall, holding his breath.

"You must warn him," she said.

The footsteps stopped shy of the door. The stone was dank against Njall's back. The tapestry smelled of cedar and smoke and mildew. "Warn him that they'll make a wolf-bitch of him? Warn him that I am handing him over to be some beast's nithling and toy? Warn him of what he already knows?"

"Hrolleif does not seem less than a man to me," Halfrid said, after a hesitation.

Njall's father snorted harsh laughter through his beard; the sound was almost a sob. Njall drove his nails into his palms, willing himself silent and still.

"Perhaps--" The sweep of her skirt across rushes. She sighed, and there was a rustle of cloth. Njall imagined she drew his father into her embrace. "Perhaps he will not be chosen. Perhaps he will be chosen by a male, and he will lead the werthreat someday himself. Perhaps he will grow to be a powerful ally to you, my lord. Your son, a wolfheofodman--"

"Perhaps is a cold word, Halfrid," Njall's father said, and then there was only silence through the doorway, until Njall slipped away.

The other older boys had returned to the dormitory, Njall's brother Jonak included, but he found he could not face them and walked out into the cold dusk instead. He crossed the courtyard once more to seek solace in the stable. His old pony Stout had been given to his sister Kathlin when he grew strong enough to handle a man's steed, but the little mare was still a friend, her shaggy wire-harsh gray mane drifting over gentle eyes. He leaned against the bar of the box she shared with two other ponies and let her drape her neck over his shoulder, steaming breath snuffing his cheek.

Kathlin found him there. She was a slip, an alf-seeming thing with the promise of their mother's looks, and all their father's temper. He wasn't surprised when she strode across the packed earth floor, stared at him for a moment, her chin lifted defiantly, and kicked him hard in the shin.

She got her hip into it. "Ow!" he protested, and was about to grab her and pick her up off her feet when she lunged forward, dissolving into sobs with the immediacyof a child. "Kathlin," he said, hopelessly. She cried harder, thumping his chest with both hands doubled up around the leather jerkin.

"You're leaving," she accused between sobs. "Father says you won't come back and I'm not to visit you. And Alfleda said she won't ever come back--"

"Did he say I was forbidden?" Njall asked, stroking her shoulders. She shook her head, her face pressed into his shirt. The tears soaked the cloth so cold bit through. Stout nickered and nosed Kathlin's hair, which made her laugh, and sniffle, finally, although she didn't step back.

"Don't go."

He hugged her tight. She was warm, but shivering. Her bones were too big for her flesh--she was growing, and felt stretched out over them. "I have to." He brightened, though. "I'll come visit you. When I can. If they let me."

"Won't they let you?" She stepped back, smoothing her dress, self-conscious enough to give him her shoulder. Younger than he by summers, but suddenly like a woman grown. "They can't keep you locked up, can they? I mean, wolfcarls aren't supposed to have families. You can't marry, you can't ... It's in all the songs. You're just going to fight the trolls until you die."

"They may not even take me," he said, and reached out to grab her shoulders. "Come on, Kathlin," he said, when he felt that she was shivering still. "Come inside before Nurse finds you missing, or you freeze. They probably won't take me. And if they don't, I'll be home by harvest, and our debt to the wolfheall will be paid."

She glanced at him under her lashes, her eyes startlingly blue. "Promise?"

"Promise," he said, and squeezed her tight before he hurried her inside.

He slept little and uneasily, rising well before dawn to wash and dress. His father had not sought him out,neither to tell him he was being sent to Hergilsberg--and Njall knew, with some surprise, that his mother was right: if his father had proposed that plan, he would have refused--nor to speak with him plainly, as man to man, about the customs of the wolfheall. Njall was not sure if he was glad or sorry, as he was not sure if he was glad or sorry that his father had not come to bid him farewell. The one thing he did know was that he would not have his house's duty to the wolfheall unfulfilled through his cowardice. No matter what they did to him, it would be better than knowing himself craven.

The tithe-wagon was in the courtyard, thralls loading it with sacks of turnips, barrels of salted herring. Halfrid stood beside the great, patient horses, stroking their noses while the tired-eyed wagoner swallowed the last of a hasty breakfast.

"Mother," Njall said awkwardly, and she turned and smiled at him, her eyes as warm and steady as ever.

"Are you ready, Njall?"

"I suppose," he said and then in a low-voiced rush, "Ready for what?"

"To attend the tithing. To become a man of the werthreat if you should be chosen. To defend Nithogsfjoll, keep and steading, with your life." She sighed and pushed an escaped tendril of wheat-fair hair behind her ear. "It is not the path to manhood I would have chosen for you, but it is an honorable path."

"Father said ... ." But he could not speak the word "nithling" to his mother. He blushed, and mumbled at his boots, "Father said it was my choice, but I fear I have chosen wrong."

The thralls were almost finished loading the wagon, the wagoner making some joke and swinging onto the wagon-seat. Njall looked up and saw his mother's face grim and rather sad. "You've heard stories, of course. Boys talk."

"Yes. But it's not--you said it was honorable, to go to the werthreat. I could protect you. I could--"

She kissed his brow swiftly and said, "You must decide what your honor is, Njall, and hold to it. I know men who have gone to the wolfheall and made a warrior's life there. You can too. Or you can come home, and we will have you."

"Father won't," Njall said.

"Your father has his own trolls to hunt," Halfrid said, and might have continued if the wagoner had not interrupted when she took a breath.

"Begging pardon, Lady Halfrid, but we haven't got all day. They like you to be timely at the wolfheall, so they do."

"Go on with you, then," Halfrid said to Njall. "You have your mother's blessing."

"Thank you," Njall said and climbed up into the wagon.

All the way down from keep to wolfheall, he pondered his mother's words. You must decide what your honor is. But honor was honor, wasn't it? It wasn't something you could pick and choose about. Yet she would not have wasted her breath with meaningless words.

But they reached the great barred gate of the wolfheall's wall before he had puzzled out her meaning.

Even as the wagoner was drawing his horses to a stop, the gate was opening, and a man came out, his hair iron-black and his face like something carved from flint, a trellwolf beside him that seemed the size of a bear. Even the great carthorses shied and stamped at the sight of that monster, and Njall's palms grew clammy. This wolf's eyes were more orange than those of Hrolleif's bitch and his heavy pelt rippled like water over his muscles. Njall recognized the man, just as he had recognized Hrolleif: Grimolfr, the wolfjarl, who ruled the wolfheall as Njall's father ruled the keep. Njall swallowed hard.

"So," said Grimolfr, while his wolf sat beside him and let his tongue loll. "You are Njall Gunnarson. It seems I owe Hrolleif a forfeit. I wagered you would not appear this morning."

Njall slid down from the wagon. "My house honors its duty to the wolfheall," he said.

"As well it should. Did you bring anything?"

"No."

"Good. That's less we have to get rid of. Come along."

He turned on his heel and strode into the wolfheall compound, calling for the thralls to come unload the wagon. His wolf moved with him as swiftly and surely as his shadow. Njall followed him, because whatever his honor might be, it certainly didn't include succumbing to the childish impulse to plant his feet and refuse to budge.

The wolfheall wasn't a grand stone keep like his father's. The walled compound was halfway flagged--and a good thing, too, because the feet of men and trellwolves had churned what wasn't paved into a springtide mire--but the central building was a roundhall in the old style, wooden, roofed in slates, a thick stream of smoke ascending from its center. The whole bustled with activity: wolves and men and thralls at work all about. Njall saw two men enter at the postern gate, a pole slung over their shoulders with a dead buck dangling from it. Two wolves paced them, one a red so pale he was almost tawny, the other dark as smoke, like Grimolfr's gigantic male. Will my wolf be gray? Njall wondered. If I am chosen?

He snuck a glance sideways at Grimolfr's male, and wondered if it was the father of Hrolleif's bitch's pups. And then he thought of the shocking things that were whispered by older boys to younger in the dormitories at night, thought of his father's brutal words; he looked up at Grimolfr and blanched at his imaginings.

"Vigdis won't whelp tonight," Grimolfr said, without returning the stare. "Tomorrow, perhaps. Have you eaten, pup?"

The wolfjarl's voice was not unkind, and Njall decided to risk honesty. "I haven't been hungry, sir. Are ..."

"Speak, whelp. Wolves say what they think when they think it; we have our politics, but they're not devious ones."

"I was going to ask where you were taking me."

"To Ulfmaer, the housecarl, and his brother. They have charge of pups, wolf and man, until they're bonded. Any other questions?"

Njall had thousands, but he settled for the first one to come to mind. "Is Vigdis the name of Hrolleif's bitch--I mean, sister?"

"One of her names," Grimolfr said, unexpectedly soft and fond, allowing a little smile to curl his lips under his beard. He did glance down then, and Njall found himself pinned on the man's dark-brown gaze as surely as he'd been pinned on Vigdis'. "My brother is called Skald. His own name--" The wolfjarl gestured, and Skald turned his head, staring into Njall's eyes with his own sunset-colored ones.

Njall smelled ice and cold wind, a musk like serpents, the dark metal of old blood. "Like a kill at midwinter," he said, coughing, and then realized what it meant. "Their names are smells."

"Aye," Grimolfr said, sounding pleased although he did not smile again.

"And Vigdis? What is her name?"

It was the scent of a wet dawn in late autumn, bare trees and pale sunrise and the leaf-mold sharp and crisp at the back of Njall's sinuses. He drew a deep, hard breath, and sighed.

"You like that, whelp?"

"Yes. Sir." No, no point in lying. None at all.

"Hmh." A grunt, a dog-sound, almost animal. Njall startled, but Grimolfr didn't seem to notice. Instead, he jerked his chin at the buck, dripping icicles of blood from a slashed throat as its bearers went past, the wolfcarls who bore it nodding respect to their jarl. "Well, you'd best eat when that game is served, pup. We hunt tonight and you'll need your strength."

They had all but crossed the yard. Njall sighed relief when they entered the wind-shadow of the roundhall. "Hunt, sir? What do we hunt at night?"

Grimolfr paused with his hand on the great copper-sheathed door. "Foolish puppy," he said, and showed Njall his teeth. "We hunt trolls."

Njall was relieved that the meat he was served for noon meal was cooked--and not, he judged, actually the buck that the wolfcarls had brought home that day. This was seasoned meat, hung until tender and roasted sweet. The wolfheall's cook knew his--or her--business.

Njall shared his trencher with a slight blond boy, Brandr, who'd arrived a few days earlier and who was full of gossip and good cheer. There were six boys in all, and Njall was sure that Ulfmaer thought that too few to give Vigdis' pups good selection. The stout gray-haired housecarl traded doubtful glances with his gray-faced trellwolf throughout the meal, his uncertainty making Njall feel gangly and grimy and much younger than his years--but the hall itself wasn't unlike his father's hall, except larger, and wood instead of stone, and the dogs gnawing bones and squabbling over their portions alongside the tables weren't dogs at all but wolves as big as men.

Njall did notice that Grimolfr sat at one end of the long table and Hrolleif at the other, just as Njall's father and mother sat--and that Skald stood guard over Vigdis while she lay by Hrolleif's chair and ate, and permitted no other wolf or man near her. Nor was it lost on him that the fond looks Grimolfr sent the length of the table included not just wolf and bitch but red-bearded Hrolleif as well.

Njall found himself pushing the meat on the trencher over to Brandr's side. Brandr accepted with a glance and a shrug. Njall watched Brandr make short work of the venison, because it allowed him not to look at Hrolleif, until Ulfmaer's knotted hand descended on his shoulder.

"Njall. Nerves about the hunt?"

"Yes," Njall lied, twisting his head to look up at the housecarl.

Ulfmaer smiled, a gap-toothed grin, and squeezed his shoulder. "We'll find you weapons after the meal," he said. "In the meantime, you must eat, lad." Lad, and not pup. That one word unknotted the tangle of fear in Njall's breast a little. "I know something you can think on to distract yourself."

"What?" Not meaning to sound so eager, but there it was.

"If you are chosen--and Vigdis has at least four pups in her, so the odds are good--you'll need a name."

"A--sir, a name?"

Brandr elbowed him. "Idiot. You don't think they're all born named 'Wolf.' Ow!"--as Ulfmaer cuffed the back of his head.

"Respect for your packmates, whelp," he said, and stomped off.

Brandr waited until he was out of earshot and then slid Njall a sly look, and grinned. "Old bastard. You know Hroi's his second wolf?"

"You can have more than one?" Njall blinked, surprised.

"Even wolves get killed by trolls," Brandr said. He made a long arm that would have gotten Njall or his brother clouted, and ripped a wing off the goose three places down the table. "I hear his first wolf was a bitch, and he misses it. Makes him cranky."

"Oh," said Njall, and blushed. "What will you ... I mean, have you thought of a name yet?"

Brandr made an expressive face. "My uncle's a wolfcarl--not here, in the wolfheall at Arakensberg. He made me promise I'd call myself Frithulf, after a friend of his who died."

"And will you?"

"I promised," Brandr said with a shrug, and Njall was relieved to realize that meant yes. Maybe honor would not be so difficult to hold here after all.

He was still thinking about that, chin on his fist and brow furrowed, when Brandr nudged him. There was--not a commotion, but a disturbance--at the head of the table, and Brandr bounced on the bench. Njall looked up; a tall spidery dark man was rising from his seat. "Skjaldwulf,"Brandr hissed, leaned so close to Njall's ear that Njall could feel him jitter. "Skjaldwulf Snow-Soft, they call him. We're in luck."

"Soft! That's a name for a wolfcarl?"

Brandr snorted. "Soft as a knife in the ribs. He nearly never talks," he explained. "But he can sing."

The tall man pushed black braids behind his shoulders and picked his way over snoring wolves on the rush-and-fur-strewn floor. When he had found a clear place to stand by the fire, he scuffed his feet wide and settled comfortably, eyelids lowered. One of the older tithe-boys brought him a horn of ale. He quaffed it and handed it back, and took a deep breath, running his gaze across the wolfcarls and tithe-boys and thralls spread around the hall.

The room went silent, as Njall was accustomed when someone was about to declaim. And Skjaldwulf Snow-Soft spoke in a resonant, carrying baritone that sounded as if it rose from the depths of the earth, carrying smoke and rain.

"Winter is long, and the nights are cold. There was a time when men maintained mere dogs to guard their cattle, when there were no wolfheallan and no wolfcarls, when trellwolves were troth-enemies of true-men. When fell trolls, terrible tyrants, walked in winter as they willed it, and our forefathers shuddered in shallow scrapes. This was the time of Thorsbaer Thorvaldson, who first knew a konigenwolf and swore to serve her for salvation.

"I took this tale from Red Sturla in his age, and as he told it me I tell it you. This was the time--"

Njall listened, enraptured. There had been better skalds at his father's hall, now and again, but not many--and there had been worse, as well. Skjaldwulf's voice rang like a brazen bell when he raised it, and the alliteration tolled from his tongue with heavy power. And Njall had not heard this tale before.

Skjaldwulf--Snow-Soft, and now Njall saw another reason for the kenning-name, for he was subtle and chill in his wit, as well--told it with precision and deftness. How Thorsbaer Thorvaldson had been cast out for sorcery, forplaying at women's magic, and how he had found--alone--a daytime encampment of trolls.

It would have been worth his life to attack them. And he could not return to his jarl's keep, even with a message of grave urgency--he'd die on the point of a spear before he spoke three words.

But perhaps he could send a message somehow, or raise a warning. Perhaps he could spoil their ambush, when night came.

He waited.

And with sunset--not that the sun ever rose but briefly, so deep in winter--the wolves came. When he saw that they had come to hunt the trolls, Thorsbaer Thorvaldson fell in with the pack.

And the pack, to his shock, permitted it. He'd half-expected to be pulled down with the trolls, treated as prey. Instead, he found himself moving with the wolves, dreaming--so said Skjaldwulf--with the wolves.

Until all the trolls were dead.

Thorsbaer's jarl would not take him back on the stren

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...