17 & Gone

- eBook

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Seventeen-year-old Lauren is having visions of girls who have gone missing. And all these girls have just one thing in common—they are 17 and gone without a trace. As Lauren struggles to shake these visions, impossible questions demand urgent answers: Why are the girls speaking to Lauren? How can she help them? And . . . is she next? Through Lauren’s search for clues, things begin to unravel, and when a brush with death lands Lauren in the hospital, a shocking truth changes everything.

With complexity and richness, Nova Ren Suma serves up a beautifully visual, fresh interpretation of what it means to be lost.

Release date: March 21, 2013

Publisher: Speak

Print pages: 384

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

17 & Gone

Nova Ren Suma

HE and I were different, too, but I don’t want to forget all the good things about him. Like how he’s fearless when it comes to braving heights, or breaking and entering; he once scaled the side of my house to reach an open window when I’d locked myself out, balancing on a flimsy gutter high up over the backyard, holding on by his fingertips. There was the way he’d go ahead and do something with me, simply because I asked him to. He didn’t need to know why.

Like right then, in the snow. He was lifting the lock to take a look. A puff of his cold breath hung between us, as if reaching out to touch me, but I was just out of range. Just.

There I was, watching flurries fall and catch in his hair, those unruly curls of his poking out from under his hoodie, wishing I could tell him about Abby. But Jamie didn’t believe in things like ghosts. And how do you tell a sane, rational person that you’ve had an encounter with one? That you’ve connected somehow with a girl whose face you found on a poster? A girl who went missing right here? How she’s reaching out to you, you’re sure of it? How she’s trying to communicate something, though you can’t quite make out the message?

I think bringing him with me was my way of telling him—but no matter what screamed out in the dark of my head while we stood there together at the gate, I guess he couldn’t hear if I didn’t open my mouth and let it out.

OTHER BOOKS YOU MAY ENJOY

Catalyst Laurie Halse Anderson

Dreamland Sarah Dessen

Extraordinary Nancy Werlin

If I Stay Gayle Forman

Imaginary Girls Nova Ren Suma

Looking for Alaska John Green

The Sky Is Everywhere Jandy Nelson

Spirit Walk Richie Tankersley Cusick

Trance Linda Gerber

Willow Julia Hoban

Wintergirls Laurie Halse Anderson

— — —

GIRLS go missing every day. They slip out bedroom windows and into strange cars. They leave good-bye notes or they don’t get a chance to tell anyone. They cross borders. They hitch rides, squeezing themselves into overcrowded backseats, sitting on willing laps. They curl up and crouch down, or they shove their bodies out of sunroofs and give off victory shouts. Girls make plans to go, but they also vanish without meaning to, and sometimes people confuse one for the other. Some girls go kicking and screaming and clawing out the eyes of whoever won’t let them stay. And then there are the girls who never reach where they’re going. Who disappear. Their ends are endless, their stories unknown. These girls are lost, and I’m the only one who’s seen them.

I know their names. I know where they end up—a place seeming as formless and boundless as the old well on the abandoned property off Hollow Mill Road that swallows the town’s dogs.

I want to tell everyone about these girls, about what’s happening, I want to give warning, I want to give chase. I’d do it, too, if I thought someone would believe me.

There are girls like Abby, who rode off into the night. And girls like Shyann, who ran, literally, from her tormentors and kept running. Girls like Madison, who took the bus down to the city with a phone number snug in her pocket and stars in her eyes. Girls like Isabeth, who got into the car even when everything in her was warning her to walk away. And there are girls like Trina, who no one bothered looking for; girls the police will never hear about because no one cared enough to report them missing.

Another girl could go today. She could be pulling her scarf tight around her face to protect it from the cold, searching through her coat pockets for her car keys so they’re out and ready when she reaches her car in the dark lot. She could glance in through the bright, blazing windows of the nearest restaurant as she hurries past. And then when she’s out of sight the shadowy hands could grab her, the sidewalk could gulp her up. The only trace of the girl would be the striped wool scarf she dropped on the patch of black ice, and when a car comes and runs it over, dragging it away on its snow tires, there isn’t even that.

I could be wrong.

Say I’m wrong.

Say there aren’t any hands.

Because what I sometimes believe is that I could be staring right at one of the girls—like that girl in my section of study hall, the one muddling through her trigonometry and drawing doodles of agony in the margins because she hates math. I look away for a second, and when I turn back, the girl’s chair is empty, her trig problem abandoned. And that’s it: I will never see that girl again. She’s gone.

I think it’s as simple as that. Without struggle, without any way to stop it, there one moment, not there the next. That’s how it happened with Abby—and with Shyann and Madison and Isabeth and Trina, and the others. And I’m pretty sure that’s how it will happen to me.

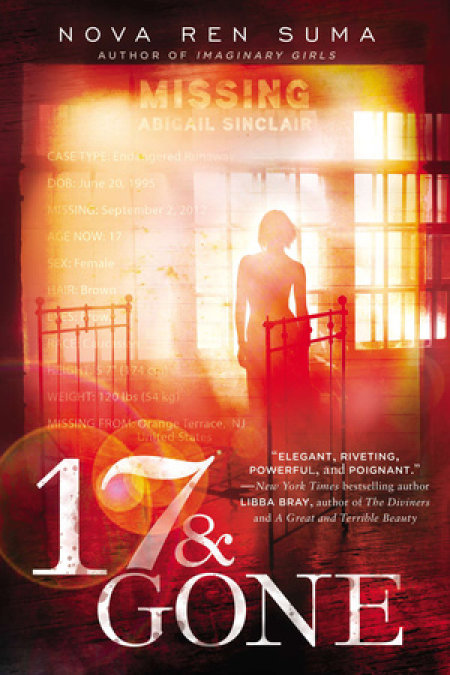

MISSING

ABIGAIL SINCLAIR

CASE TYPE: Endangered Runaway

DOB: June 20, 1995

MISSING: September 2, 2012

AGE NOW: 17

SEX: Female

RACE: Caucasian

HAIR: Brown

EYES: Brown

HEIGHT: 5' 7" (174 cm)

WEIGHT: 120 lbs (54 kg)

MISSING FROM: Orange Terrace, NJ, United States

CIRCUMSTANCES: Abigail, who more often goes by the nickname Abby, was reported missing September 2 but may have been seen last on July 29 or July 30 on the grounds of Lady-of-the-Pines Summer Camp for Girls in the Pinecliff area of New York State. She was said to be riding a blue Schwinn bicycle off the campground after the 9 p.m. lights-out. She may have been wearing red shorts and a camp counselor T-shirt. Her nose is pierced. Her family does not believe she returned to New Jersey.

ANYONE HAVING INFORMATION SHOULD CONTACT

Pinecliff Police Department (New York) 1-845-555-1100

Orange Terrace Police Department (New Jersey) 1-609-555-6638

SHE’S Abigail Sinclair, brown hair, brown eyes, age 17, from New Jersey—but I call her Abby. I found her on the side of the road in the dead of winter, months after she went missing.

Abby’s story started in the pinewoods surrounding my hometown. The seasons changed and the summer heat faded, and no one knew yet. The dreamland hung low in the clouds, smoke-gray lungs shriveled with disease, and no one looked up to see. The snow came down and the bristly trees shuddered in the wind, sharing secrets, and no one stopped to listen. Until I did.

I was forced to stop. My old van made it so, as if someone had tinkered with the engine, knowing it would hold out down my driveway and onto this main stretch of road, until here, where the pines whispered, it would choke and give out and leave me stranded.

I drove this road practically every day—to school and to the Shop & Save, the supermarket on the outskirts of Pinecliff where I stocked shelves and worked the registers on Saturdays and a couple afternoons during the week. I must have passed this spot where the old highway meets Route 11 hundreds of times without realizing. Without seeing her there.

She came visible seconds after my engine gave out, as if a fog had been lifted from off the steep slope of our railroad town that mid-December morning.

Abby Sinclair. There at the intersection. I’m not saying she was there in the flesh with her thumb out and her hair wild in the wind and her bare knees purpled from cold—it didn’t start out that way. The first time I saw Abby, it was only a picture: the class photograph reproduced on her Missing poster.

When the light turned green and traffic started moving, I wasn’t moving with it. I was arrested by the flyer across the road, that weathered, black-and-white image of Abby, with the single bold word above her forehead that pronounced her MISSING.

I remember being dimly aware of the cars behind my van honking and swerving around me, some drivers flipping me off as they blasted past. I remember that I couldn’t move. The van, because the engine wouldn’t start, and my body, because my joints had locked. The green light dangling overhead had cycled through again to yellow—blinking, blinking—then red. I knew this only from the colors dancing on the steering wheel, which I held in two fisted hands, so my knuckles that had been green, then yellow, were now red again.

Ahead of me, where the old highway halted in a fork, a stretch of pine trees braced themselves against the biting wind. The pines were weighted down by weeks’ worth of snow, but they still moved beneath it, unable to keep still. The slope of ground between them and the road was white and pristine, not a footprint to mar it. Centered within all of this was the telephone pole and, hung there as if displayed on the bare walls of a gallery, the missing girl’s face.

I left my van door swinging open, keys in the ignition, backpack on the front seat, and abandoned it to run across the intersection toward the stretch of pines. A pickup truck skidded; a horn shrieked. A car almost met me with its tires, but I moved out of the way before I could feel the bumper’s touch. I was vaguely aware of a big, yellow vehicle stopping short behind me—the school bus, the one I rode before I got my license and saved up to buy the old van—but by then I’d made it to the pole.

I trampled through the snow to get close. The flyer was old, the date she was last seen long passed. Her photocopied picture had been duplicated too many times for much detail to show through the ink on ink, so with all those layers smudging away her face, and with the snow spatter and the fade, she could have been anybody really, any girl.

By that I mean she could have been someone who had nothing to do with me. Someone I’d leave attached to the pole on that cold day, someone I’d never think of again in this lifetime.

But I knew she wasn’t just any girl. I had a glimmering pull of recognition, burning me through and through, so I couldn’t even sense the cold. I’d never felt anything like it before. All I knew is I was meant to find her.

The flyer had only facts. She was 17—like I was; I’d just turned 17 the week before. She’d gone missing from some summer camp I’d never heard of—though it was around here, in the Pinecliff area, near this place that overlooked the frigid, gray Hudson River from the steep hill on which our town was built. The commuter train that ran alongside the river stopped here nearly every hour during the day, and crept past at night. The summer camp had to be close.

I tore the page from the pole, ripping it loose from where it was stuck fast with packing tape that had been wound and wound around the pole to keep her from falling face-first into the snow, or from getting carried away on a gust of exhaust and escaping into the traffic leading to the New York State Thruway. It was the clear tape covering the details on the flyer that had kept it from disintegrating for all these months. It was also the tape, so much of it, that made it almost impossible to tear her free.

When I crossed the intersection again—more horns honking—and reached my van, I saw that some Good Samaritan (or a creeper disguising himself as a Good Samaritan) had stopped his own car on the shoulder to offer help. There was some tinkering with the engine, mention of a possibly busted fan belt, and a plume of gray smoke that spat itself into the man’s face and then lifted up into the bone-white air overhead, a blot of hate on the sky that already threatened more snow. There was a tow I couldn’t afford, and an hour waiting on a greasy folding chair in the back of the garage because it was too cold to wait outside. It wasn’t until they fixed my van and I was headed in late to school that I had a moment alone to take a closer look at the flyer.

I didn’t tell Jamie or Deena, or anyone. There wasn’t anyone I wanted to tell. This discovery was mine, and I wanted to hold it close.

My heart had an irregular beat that I can almost hear again now, like an extra thump was thrown in to make me think there were two hearts in the van, thumping.

There were—but I wasn’t aware at first. This was before I knew she followed me.

I’D parked in the senior parking lot even though I wasn’t a senior, cut the engine, and was sitting there holding it. The flyer. The paper was the same temperature as my fingers—cold—so I couldn’t feel either.

I tried to flatten the paper against the steering wheel, smoothing the tears and wrinkles from her face as best I could to study what they said about her.

“Endangered Runaway” they called her. A sliver of fear entered me when I saw they said she was in danger, but now I know that everyone under eighteen who goes missing is called endangered. On Missing posters, if you’re not an “Endangered Runaway,” you’re “Endangered Missing,” but you’re always in danger—it’s never a “She’s Probably Doing Okay, But We Have to Check Since It’s the Law” missing girl.

Besides, Abby was in danger. I felt it.

I pored over her flyer again, learning her hometown, her hair color, her eye color, her weight and height. I learned that she was gone before she was reported missing, and I didn’t understand why. I learned of her pierced nose. I didn’t learn about her habit of writing the name of the boy she liked on the inside of her elbow, then spitting on it and rubbing at it till it was clean. That information wasn’t on the flyer, and this was before she told me.

I would have pocketed the piece of paper and gone into the school building, and maybe all of what happened next would have been different, but that’s when I saw the light.

My Dodge van had one of those cigarette lighters built into the dashboard, a knob beside the stereo that you press in to heat. It glows orange, and then when it’s ready to use, it pops back out. I’d had the van a couple months, but I’d never used the lighter.

Now the knob was pressed in. An orb of fire-orange was blazing from the dashboard as if someone had reached out an arm to light a cigarette. A phantom cigarette and a phantom arm, because I was alone in the van. I was alone.

I told myself I must’ve knocked the lighter when I parked. Or the mechanic who’d fixed the engine got it stuck. It’s been lit up, I assured myself; it’s been on the whole time.

I looked out at the quiet parking lot, a white expanse beneath the rising ridge above the school. Nothing stirred.

This was when something streaked past outside: a fast-moving blur, as if someone were sprinting the length of the school property. Someone wearing red.

My temples hammered, and I screwed my eyes shut. I lost my grip on the flyer and felt it fall to the floor. There were stars clouding my vision, stars that became one star, until then, there: the sparkling cubic zirconia in her left nostril.

She was visible in the van’s rearview mirror when I opened my eyes. Bright and searing like a sunspot, until my eyes adjusted, or her heat dimmed enough so I could see her clearly.

She’d taken the middle bench seat, the collapsible one I hadn’t bothered to collapse all week, as if I’d known to expect her company. This seat was just behind mine, but I didn’t turn around. I could say that I didn’t want to make any sudden movements, that I was trying not to scare her away, but truth is I couldn’t. My body wouldn’t move for me at all.

Her reflection in the rearview showed her face at eye level. Her shoulders hunched. Her two bare knees folded to her chin, purplish blooms of bruises on her shins like she’d crawled across the icy asphalt lot, slithering between parked cars, to reach my black van.

This was Abigail Sinclair from the Missing flyer. I could smell her, harsh and hot like a tuft of hair burning.

She uncrossed her arms and lowered her knees, and I noticed that her T-shirt had the name of the summer camp and a picture to go with it: a veiled lady lifted up above a trio of pine trees, as if in the midst of being taken herself. The shirt was covered in grime and streaked with mud, so the words COUNSELOR-IN-TRAINING could barely be made out above her heart. Below the shirt, I saw she had on a pair of shorts. Red ones, with thin white racer stripes. She had been on the home team in Color War that day—I found that out later.

She was letting me see what she was wearing on the night she disappeared, but I knew, even then, that this wasn’t about what a girl was wearing when she found herself gone. Nothing she could have worn on that night would have made a difference. Not these shorts or another pair that were longer or less red. Not a bathing suit. Not a bear costume. Not a short skirt. Not a burqa.

There was so much more to her story I didn’t know.

“Abigail?” I said. It came out in a whisper.

Without a word or warning, my vision shifted. I was soon seeing through some layers of smoke and coughed-up haze into what she herself saw the night she went missing. This seeing was more like knowing. I didn’t have to question it—in the way that I can be sure, without needing to check first, that there are five fingers on my hand.

What I came to know was this:

She didn’t like it when people called her Abigail. So I wouldn’t, not anymore.

And she did ride away on that bike, though it was green, not blue as had been reported. What I saw of her—what she willed me to see—was a moving image spooling out in the frame of my rearview mirror, a home movie projected in an empty theater for me and only me.

There she was, riding a bright green bicycle into a sea of darkness. That was her, coasting on a gust of wind and letting her long hair untangle and fly. It was a rusty old bike, one she borrowed from the counselor’s shed; it was an empty road, one on which no cars passed; it was a slick, sweet-smelling summer’s night.

That was it, that was the last of her. She lingered on it, and so did I, holding the memory between us like something sweet slowly licked off a shared spoon.

I watched the reflective light mounted on the back of the bicycle catch and glow and grow small as she traveled into the dark distance. Watched her pedal, quick at first, then slowing to coast down the hill. Watched as she lifted both arms from the handlebars for a heartbeat of a second, then put them back down and held on. I watched her go.

Then I lost sight of her. The bike dipped under, but the image of the road stayed still. I was leaning forward, trying to see farther, when the mirror went dark and I realized someone was pounding on the window of my van.

My neck turned until I was face-to-face with the intruder.

It was Mr. Floris, ninth- and tenth-grade biology teacher by trade and prison guard in his dark dreams and deepest fantasies. Everyone knew Mr. Floris loved trolling the school grounds during his free periods, itching to hand out detentions. And even though it was no surprise to find him in the parking lot seeking to foil late sleepers and slackers, it was still a shock to be caught. I’d forgotten where I was.

He rapped his knuckles on the glass, then lowered the red scarf that he’d wound around his face to keep out the cold. When his mouth was free, I saw the chapped lips beneath his mustache shape out the words: You. Roll down this window this instant, young lady.

There was only a single layer of window glass between us, but I couldn’t hear him. I heard nothing but the distant whirring of two bicycle wheels. Then he pounded again, and I heard that and flinched and was rolling down the window and saying, “Sorry, Mr. Floris. I didn’t see you there.”

At the same time I was taking another glance in the rearview mirror, needing to know—was she still in the van with me? Was she huddled behind my seat, in the dark cavern in back? But something was blocking my view: the reflection of the pale girl in the mirror who must have been rubbing at her eyes again, a bad habit. She had smoke-gray tracks of mascara streaking down her cheeks as if she’d been holed up in the van crying. She wasn’t. I hadn’t cried in years.

On top of my head was the puffy wool hat my friend Deena Douglas stole from the mall and didn’t like on herself and so gave to me. The hat was pulled low over my eyebrows, hiding my ears and hiding the view of the backseat where Abby still could be.

“Miss Woodman,” Mr. Floris said, “you do realize it’s third period and you should be in class? Get out of this van and come with me or I’ll have to write you up.”

I’d never been written up before. This was before I started skipping all that school, before the “marks” on my “permanent record” that I’d “regret” for the “rest of my life.” This was before I shattered into the particles and pieces I’m in now.

Even so, I didn’t get out of the van.

“But . . .” I said, pausing there, waiting.

Because didn’t he see?

I was expecting him to notice her behind me. He was close enough to my window that he must have been able to see the bench seat and who was in it. There . . . the apparition of a girl hiding behind her hair, wasn’t she there with her grimy face and her scratched-up knees?

I could still smell her. I could sense her breathing, too, her mouth sharing air with my mouth even though logically I knew it wasn’t possible.

But Mr. Floris’s eyes landed on something else: The lighter in my dashboard had thrust itself out with a hard pop.

“That’s it, Lauren, get out. Now. I’m writing you up.”

He didn’t see—he was blind to it. To her. Soon enough he was opening the door for me and waving me out onto the icy pavement. I glanced directly at her only once, when I was reaching down to rescue her flyer from the floor.

Her long hair was tangled with leaves, I noticed then, stuck through with loose green leaves and pine needles and matted with twigs and sap. One bruised knee was bleeding, and the trail of blood had wound down her leg to between her toes. She was wearing one flip-flop. The other had been lost somewhere I couldn’t imagine.

I knew she fell off the bicycle; I could see it happening, a loose rock under her tire catching her off-balance in the dark depths of the night. But did she get up again, or did something stop her? What and who did she meet at the bottom of that hill?

She didn’t say. I wouldn’t have expected her to tell me in front of him, anyway.

I stepped out of the van, closed and locked the door, and followed Mr. Floris to the front office, where I was about to be awarded a block of after-school detention. But I did look back. I kept looking back. Nothing would keep me from looking for her now.

— — —

That was the first time I was visited by Abby, who met her fate outside the Lady-of-the-Pines Summer Camp for Girls. Now, there are so many more things I know about her.

She’s Abigail Sinclair of Orange Terrace, New Jersey. Yes, there’s that. But she’s really only Abigail to her grandparents and her homeroom teacher. To everyone else, she’s Abby.

Abby with the smallest speck of a stud in her nose, so it looks like a sparkling star has been plucked from the sky and hung low beside her face, a star that follows her wherever she goes, night or day. Abby who chews her nails, just the ones on her thumbs. Abby who never wears skirts. Abby who’s afraid of clowns and isn’t kidding when she says so. Abby who doesn’t mind when it rains. Abby who played flute, for three months, then quit. Abby, solid C student. Abby, still a virgin, on a technicality, which does count. Abby who can tap-dance. Abby who can’t whistle, no matter how hard she tries. Abby who likes, maybe even could have loved, Luke.

Abby with brown hair, brown eyes, 120 pounds, 5'7", small scar on her right knee from tripping over the back step when she was five.

Abby: age 17, reported missing September 2, but gone before that, gone in summer and no one went looking.

Gone.

I don’t know how I made it through the day I first found Abby.

My memory holds on only to vague pieces, because other, sharper things have since come to take their place. I remember the detention slip for cutting class and smoking in the parking lot, torn ragged on one side so it looked like someone had taken a bite out of my sentence, but I don’t remember the detention itself. I don’t remember what happened in my classes or what I learned, if anything. I don’t remember lunch period with Deena, and what particular kind of slop-on-a-tray I carried to our table and then put in my mouth. Or what plans she made for her eighteenth birthday party, which was all she could talk about even though it was weeks and weeks away. Or anything else she said.

At one point there was my boyfriend, Jamie Rossi, at my locker, asking what happened and why I was late, and I remember this because it was the first time I had ever kept something from him.

“Just engine trouble,” I heard myself telling him, “that’s all.” I didn’t say anything about a girl taped to a telephone pole, a girl hidden in the back of my van. It was still possible I’d imagined it. Imagined her.

I have this freeze-frame of Jamie in my memory, this picture. In it, the hood of his sweatshirt is popped up over his head, and the dark curls over his forehead are spilling out because he needed a haircut again like he seemed to practically every other week. He’s leaning in, eyes closed so I see how long his lashes are. And there are his lips out to meet mine. His stubble showing, but only on his chin, because he couldn’t grow a full beard, not if he tried. I can’t tell what he’s thinking—if he believes me—because his eyes are closed. Not that I could ever guess, with Jamie. He’s a guy, so he’s used to keeping things close.

Then the picture of Jamie’s face falls away, and I must have kissed him back, or a teacher came by and stopped us, but I don’t remember that part.

I was outside myself, as if I were standing at the dip in the highway that led to Pinecliff Central High School, the last place you could turn before heading to school, all while some shadow-me was inside the building going to my classes, kissing my boyfriend, answering to my name when it was called.

I couldn’t get Abby out of my mind.

During my free period, I did a search online, on one of the library computers, and found a listing in the missing persons database for an Abigail Sinclair from New Jersey. That flyer on the telephone pole may have been a few months old, but she was still out there somewhere. She was still 17 years old. Still missing.

There was also a public page online that her family or friends must have made for her—a memorial of sorts where anyone could post a message:

ABBY! IF YOU ARE READING THIS! Come home! We miss you.

------------------------------------------------------

Abigail, it’s your cousin Trinity. You have Grandma and Grandpa so worried you have no idea. Where are you????? Call me if you’re reading this. We just want to know you’re ok!

------------------------------------------------------

Dear Abby, I have never met u but I am praying for u every night

------------------------------------------------------

Abbz U R missed @ school <3

------------------------------------------------------

luv you girl come home!!!!

It was when I was scrolling through this page of notes left for Abby, notes I felt sure she’d never seen, from some people she didn’t even know, that I realized a person was standing behind me, waiting for the right moment to speak.

When I turned in my chair, I watched this girl’s gaze peel away from my computer screen and go to me. I didn’t recognize her at first, and then her face took on shape and I realized she was a freshman, a girl I’d seen around school. I was more aware of the fact that she was breathing, undeniably alive, than of anything else. This girl wasn’t missing; she was right here. And all I wanted was for her to go away.

“Hey, Lauren,” she said, “we saw you this morning. Are you, um . . . okay?”

“You saw me? Where?” The thought of being watched while I was in the van alarmed me.

“Before school? You were in the middle of the road? The bus almost hit you? We all sa

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...