- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

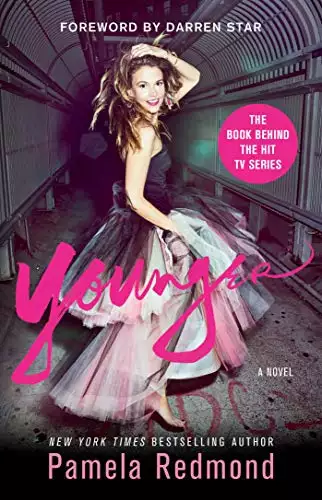

A story of inspiration and transformation for every woman who’s tried to change her life by changing herself—now a hit TV series from the creator of Sex and the City starring Sutton Foster and Hilary Duff. She wants to start a new life. Alice is trying to return to her career in publishing after raising her only child. But the workplace is less than welcoming to a forty-something mom whose resume is covered with fifteen years of dust. If Alice were younger, she knows, she’d get hired in a New York minute. So, if age is just a number, why not become younger? Or at least fake it. With help from her artist friend Maggie, Alice transforms herself into a faux millennial and soon finds an assistant’s job, a twenty-something bff, and a hot young boyfriend, Josh, who was in diapers when Alice was in high school. You’re only as young as you feel. Alice is too thrilled with her new relationship and career to worry about the fallout from her lie. But when Maggie decides she wants a baby, Alice’s daughter comes home early from studying abroad, and Alice finds herself falling in love with Josh, she realizes her masquerade has serious consequences, especially for her. Can Alice turn the magic into her real life? Or will the truth come out and break the spell?

Release date: June 4, 2019

Publisher: Pocket Books

Print pages: 384

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Younger

Pamela Redmond

chapter 1

I almost didn’t get on the ferry.

I was scared. And nervous. And overwhelmed by how out of place I felt, in the crowd of young people surging toward the boat bound for New York.

Not just New York, but New York City on New Year’s Eve. The mere thought of it made my hands sweat and my feet tingle, the way they did the one time I rode to the top of the Empire State Building and tried to look down. In the immortal words of my daughter, Diana, it made my weenie hurt.

I would have turned around and driven right back home to my safe suburban house—I can see the ball drop better on TV anyway!—except I couldn’t leave Maggie waiting for me on the freezing pier in downtown Manhattan. Maggie, my oldest and still closest friend, didn’t believe in cell phones. She also didn’t believe in computers, or cars, or staying in New Jersey on New Year’s Eve, or for that matter, staying in New Jersey ever. Maggie, who came out as a lesbian to her ultra-Catholic parents at sixteen and made her living as an artist, didn’t believe in doing anything the easy way. And so I couldn’t cancel our night out, and there was nothing for me to do but keep marching forward to my potential doom.

At least I was first in line for the next boat. It was frigid out that night, but I staked my claim to the prime spot, hanging on to the barricade to keep anybody from cutting in front of me. These kind of suburban yos who were milling around on the dock with me, I knew, majored in line-cutting in kindergarten.

Then a weird thing happened. The longer I stood there, guarding my turf, the more I began to want to go into the city—not just for Maggie, but for myself. Looking out across the dark water at the lights of Manhattan sparkling beyond, I began to think that Maggie had been right, and going into New York on New Year’s Eve was exactly what I needed. Shake things up, she said. Do something you’ve never done before. Hadn’t doing everything the way I’d always done it—the cautious way, the theoretically secure way—landed me precisely in the middle of my current mess? It had, and no one wanted that to change more than me.

And so when they opened the gate to the ferry, I sprinted ahead. I was determined to be the first one up the stairs, to beat everybody else to the front of the outside deck, where I could watch New York glide into view. I could hear them all on my heels as I ran, but I was first out the door and to the front of the boat, grabbing the metal rail and hanging on tight as I labored to catch my breath. The ferry’s engine roared to life, its diesel smell rising above the saltiness of the harbor, but still I sucked the air deep into my lungs as we chugged away from the dock. Here I am, I thought: alive and moving forward, on a night when anything can happen.

It wasn’t until then that I noticed I was the only one standing out there. Everybody else was packed into the glassed-in cabin, their collective breath fogging its windows. Apparently I was the only one who wasn’t afraid of a little cold, of a little wind, of a little icy spray—okay, make that a lot of icy spray—as the boat bucked like a mechanical bull across the waves. It was worth it, assuming I wasn’t hurled into the inky waters, for the incredible view of the glowing green Statue of Liberty and the twinkling skyscrapers up ahead.

As I gripped the rail even tighter, congratulating myself on my amazing bravery, the boat slowed and seemed to stall there in the middle of the harbor, its motor idling loudly. Just as I began to wonder whether we were about to sink, or make a break for the open seas at the hands of a renegade captain running from the law, the boat began to back up. Back up and turn around. Were we returning to New Jersey? Maybe the captain had the same misgivings about Manhattan on New Year’s Eve that I did.

But no. Once the boat swung around, it began moving toward the city again. Leaving me facing not the spectacular vista of Manhattan but the big clock and broken-down dock of Hoboken, and darkest New Jersey beyond. Frantically, I looked over my shoulder at the bright, snug cabin, which now had the prime view of New York, but it was so crowded, it would have been impossible to squeeze inside. I was stuck out in the cold facing New Jersey, all alone. The story of my life.

* * *

Half an hour later, I was hobbling through the streets of Soho arm in arm with Maggie, cursing the vanity that had led me to wear high heels and fantasizing about grabbing the comfy-looking green lace-up boots off Maggie’s feet. Maggie was very sensibly striding along beside me in skinny jeans, a down-filled coat as enormous as a sleeping bag, and a leopard-print hunter’s cap, with the earflaps down and a velvet bow tied under her chin.

“Are we almost there yet?” I asked, the shoes nipping at my toes.

“Come on,” she said, tugging me away from the crowded sidewalk of West Broadway toward a dark, unpopulated side street. “This’ll be faster.”

I stopped, looking with alarm down the deserted street. “We’ll get raped.”

“Don’t be such a scaredy-cat.” Maggie laughed, pulling me forward.

Easy for her to say: Maggie had moved to the Lower East Side at eighteen, back when Ratner’s was still serving blintzes and crackheads camped under her stairwell. Now she owned her building, the entire top floor turned into a studio where she lived and worked on her sculptures, larger-than-life leaping, twirling women fashioned from wire and tulle. All those years in New York on her own had made Maggie tough, while I was still the soft suburban mom, protected by my husband’s money, or should I say, my soon-to-be-ex-husband’s ex-money.

My heart hammered in my ears as Maggie dragged me down the black street, slowing only slightly when I focused on the sole beam of light on the entire block, which seemed, for some strange reason, to be pink. When we reached the storefront from which the light was emanating, we saw why: in the window was a bright pink neon sign that read “Madame Aurora.” The glow was further enhanced by a curtain of pink and orange glass beads covering the window, filtering the light from inside the shop. Beyond the beads, we could just make out a woman who could only be Madame Aurora herself, a gold turban askew on her gray hair, smoke curling from the cigarette that teetered from her lips. Suddenly, she looked straight at us and beckoned us inside. Taped to the window was a hand-lettered sign: “New Year’s Wishes, $25.”

“Let’s go in,” I said to Maggie. I’d always been a sucker for any kind of wish and any kind of fortune-telling, so the combination of the two was irresistible. Besides, I wanted to get out of the cold and off my feet, however briefly.

Maggie made a face, her “You have got to be out of your fucking mind” face.

“Come on,” I said. “It will be fun.”

“Eating a fabulous meal is fun,” Maggie said. “Kissing someone you have a crush on is fun. Dropping good money on some phony fortune-teller is not fun.”

“Come on,” I wheedled, the way I did when I called to read her a particularly good horoscope, or suggested she join me in wishing on a star. “You’re the one who told me I should start taking more risks.”

Maggie hesitated just long enough to give me the confidence to step in front of her and push open Madame Aurora’s door, giving Maggie no choice but to follow.

It was hot inside the room, and smoky. I waved my hands in front of my face in an attempt to signal my discomfort to Madame Aurora, but this only seemed to provoke her to take a deeper drag on her cigarette and then to emit a plume of smoke aimed directly at my face.

I looked doubtfully at Maggie, who only shrugged and refused to meet my eye. I was the one who’d dragged us in here; she wasn’t about to get us out.

“So, darling,” said the Madame, finally removing the cigarette from her mouth. “What is your wish?”

What was my wish? I wasn’t expecting her to pop the big question right out of the gate like that. I figured there’d be some preamble, a few moments examining my palm, shuffling the tarot cards, that kind of thing.

“Well,” I stalled. “Do I get only one?”

Madame Aurora shrugged. “You can have as many as you want, for twenty-five dollars a pop.”

And no fair, as everybody knows, wishing for more wishes.

Again, I tried to catch Maggie’s eye. Again, she looked stubbornly away from me. I closed my eyes and tried to concentrate.

What was the one thing I wanted, above all others? For my daughter, Diana, to return from Africa? Definitely, I wanted that, but she was scheduled to come home this month anyway, so that seemed like a waste of a wish.

To get a job? Of course. I’d been so determined to support myself when my husband left that I’d negotiated sole title to our house in lieu of long-term alimony. Then I’d spent half the year humiliating myself at interviews at publishing houses. No one, it seemed, wanted to hire a forty-four-year-old woman who’d spent precisely eight months in the workforce before becoming a full-time mom. I tried to tell them I’d devoted the past twenty years to reading everything I could get my hands on, and I knew better than anybody what middle-class suburban women in book groups—women exactly like me, who made up the prime novel-buying market—wanted to read.

But nobody cared about my experience in the reading trenches. All they seemed to see was a middle-aged housewife with an ancient English degree and a résumé padded with such “jobs” as co-chair of the book fair at my kid’s elementary school. I was unqualified for an editor’s position, and though I always told them I would be happy to start as an assistant, I wasn’t considered for entry-level jobs. No one put it this way, but they thought I was too old.

“I wish I were younger,” I said.

By the looks on Madame Aurora’s and Maggie’s faces, I must have said that out loud.

The Madame burst out laughing.

“Whaddaya wanna be younger for?” she said. “All that worryin’, who am I gonna marry, what am I gonna do with my life. It’s for the birds!”

Maggie chimed in. “What are you saying, that you want to go back to all that uncertainty? Now that you finally have a chance to get your life together?”

I couldn’t believe they were ganging up on me. “It’s just that if I were younger I could do some things a little differently,” I tried to explain. “Think about what I want more, take my career more seriously . . .”

But Maggie was already shaking her head. “You are who you are, Alice,” she said. “I knew you when you were six, and even back then you always put everybody else first. Before you went out to play, you had to make sure your stuffed animals were comfortable. When we were freshmen in high school, and everybody else was consumed with trying to look cool, you were the one who volunteered to push that crippled girl around in her wheelchair. And once you had Diana, she was always what you cared about above everything else.”

I had to admit, she was right. I may have left my job at Gentility Press because I had to, when I started bleeding and almost lost the baby. But once Diana was born, I stayed home because I wanted to. And then, as she got older, I kept telling myself I couldn’t go back to work because maybe this was the year I’d finally get pregnant again, but the truth was that Diana herself was all the focus I needed in my life.

So now I wanted to undo that? Now I wished I could go back and put Diana in day care, become a working mom, or even not have Diana at all?

The very idea was enough to send an enormous shiver up my spine, as if even the shadow of the idea could jinx my daughter, my motherhood, the most important thing in my life. I could never wish her out of existence, never dream of wishing away even one of the moments I’d spent with her.

But still, what about me? Had devoting all those years to my child disqualified me from ever claiming a life for myself? The real reason I wished I’d been different back then was so that I could be different now: ballsier, bolder, capable of grabbing the world by the throat and bending it to my will.

“What’s it gonna be?” said Madame Aurora.

“I want to be braver,” I said. “Plus maybe, if you could do something about my cellulite . . .”

Maggie rolled her eyes and jumped to her feet.

“This is ridiculous,” she said, taking hold of my arm. “Come on, Alice. We’re leaving.”

“But I didn’t get my wish,” I said.

“I didn’t get my money,” said Madame Aurora.

“Too bad,” said Maggie. “We’re out of here.”

* * *

Now Maggie was walking really fast. I tried asking her to slow down, but instead of listening, she kept forging ahead, expecting me to keep up. Finally, I stopped dead in my tracks so she had to double back and talk to me.

“Give me your boots,” I said.

She looked puzzled.

“If you expect me to walk this far and this fast, you’re going to have to trade shoes with me.”

Maggie looked down at my feet and burst out laughing.

“You need more help than I thought,” she said.

“What are you talking about?”

“You’ll see.” She was already untying her green boots.

“Where are we going?” I always trusted Maggie to be my guide to New York, following unquestioningly, like a little girl, wherever she wanted to take me. Tonight, for instance, I thought she said we were going to a cool new restaurant. But now that I took a moment to look around at the low brick buildings and decidedly uncool neighborhood as I stepped into Maggie’s boots, I was starting to wonder.

“We’re going to my place,” she said.

“Why?”

“You’ll see.”

Even wearing the heels, she walked faster than me, but at least my feet didn’t hurt anymore. And once we passed out of the no-man’s-land that still separated Little Italy from Maggie’s neighborhood, I began to relax. The blocks around her building used to be terrifying, but had improved considerably in the past few years. Tonight, the streets were full of people, and all the hip restaurants and bars were packed. Every place looked good to me—I was starving, I realized—but Maggie was not to be deterred.

“We’ll go out after,” she said.

“After what?”

She smiled mysteriously and repeated the phrase that was becoming her mantra: “You’ll see.”

It was a five-flight climb to Maggie’s loft, which I used to find daunting but now took with ease, thanks to all the hours I’d logged on the elliptical trainer in the past year. After a lifetime as a dedicated couch potato, I’d started exercising because it was the only thing I could think of, in my past year of horrible events, that would reliably make me feel good. And after a lifetime of dieting, I’d found the pounds disappearing without doing anything at all—anything, that is, except working out for an hour or two every day. I’d even, maybe twice, had a flash of that high you’re supposed to get from working out, though I still preferred a gimlet.

Coming from the suburbs, where Pottery Barn was considered the height of living room fashion, Maggie’s loft was always a shock. It was basically one gigantic room that occupied the entire top floor of the building, with windows on all four sides and a bright red silk tent sitting smack in the middle of the three thousand feet of open space—the closet. The only furniture was an enormous iron-framed bed, also bright red, and an ornate purple velvet chaise that provided the place’s sole seating, unless you counted the paint-spattered wooden floor. Which I didn’t.

“Okay,” Maggie said, as soon as she’d triple-bolted the door behind us. “Let me have a look at you.”

But I was too distracted by what was different about Maggie’s loft to stand still. All her sculptures, all her nine-foot-tall chicken-wire women, with their size 62 ZZZ breasts and their ballet skirts as full and frothy as flowering cherry trees, had been shoved into one corner, where they mingled like inmates in some prison for works of art. Now occupying the prime spot in Maggie’s work area was a concrete block as big as a refrigerator.

“What on earth is that?” I said.

“Something new I’m trying with my work,” said Maggie breezily. “Come on, take off your coat. I want to see what you’re wearing.”

Now I could finally focus. Maggie wanting to survey my clothes was never a good thing. She was always, from the time we were first able to dress ourselves, trying to make me over, and I was always resisting. Don’t get me wrong, I thought Maggie had fantastic style, but fantastic for her, not for me. Her hair had turned white when she was still in her twenties, and every year it seemed to get a little shorter and messier, standing up in tufts all over her head. As her hair got more butch, her earrings became more feminine and ornate and numerous. The featured attraction tonight was green-jeweled chandelier earrings. Maggie, whose body was still as slim and limber-looking as a teenager’s, also must have had the soul of a French woman. She had that knack for throwing on an odd assortment of clothes—tonight it was the faded jeans she’d had since high school with an antique lace-trimmed cream silk blouse and a long gray-green velvet scarf wound around her neck—that always managed to look enviably perfect.

She walked around me, rubbing her chin and shaking her head. Finally she reached out and grabbed a hank of the oversize beige sweater I was wearing.

“Where’d you get this?” she asked.

“It was Gary’s,” I admitted. One of the many pieces of clothing he’d left behind when he left me exactly a year ago for his dental hygienist. Clothing I’d kept because, for a long time, I assumed he’d come back. And continued to keep because, for the next few months at least, he was still paying the mortgage on the house where his clothes and I lived together.

“It’s a rag,” Maggie said. “And what about that skirt?”

The skirt choice I was actually rather pleased with. The same beige as the sweater, it was fitted through the hips and ended above the knee, considerably sexier than the khakis and sweatpants I’d favored for the past two decades.

“It was Diana’s,” I said proudly. “I couldn’t believe it fit me.”

“Of course it fits you!” Maggie exclaimed. “You’re a stick! Come here.”

She spun me around and tried to push me forward.

“Where are you taking me?”

“I want you to look at yourself.”

She propelled me across the loft until we were standing in front of an oval mirror with a curlicued gold frame, like the one the Wicked Stepmother communes with in Snow White.

“Mirror, mirror on the wall,” I said, laughing, trying to get Maggie to join in the joke. But she only gazed poker-faced over my shoulder, refusing to so much as crack a smile.

“This is serious,” she said, pointing her chin toward the mirror. “Tell me what you see.”

It had been a long time since I’d looked in a mirror with much enthusiasm. Sometimes, especially when Diana was small, I’d go for days without checking my reflection. And then through the years, as I got heavier, and my hair started to turn gray, and the lines began to appear around my eyes, I discovered I felt happier when I didn’t look at all. In my mind’s eye, I was forever some grown-up but neutral age—thirty-threeish—and some womanly but neutral weight—133ish—and looked acceptable if not gorgeous or sexy or notable in any way. I was always shocked when I caught sight of my reflection in a shop window or a car door and was forced to see that I was considerably older and heavier than I believed.

But now, compelled to confront my image, really take it in, for the first time in the year my life had been turned upside down and inside out, I had the opposite reaction. I lifted my chin and turned my head to the side; without thinking, I stood up taller and smiled.

“That’s right,” Maggie said. She gathered the back of my baggy sweater into her hands so the fabric was pulled tight against my newly buff body. “What do you see?”

“I see—,” I said, trying to think how to put it. There was me, staring back from the glass, but it was some version of myself before child, before husband, before all the years had clouded my vision. “—myself,” I said finally, lamely.

“Yes!” Maggie cried. “It’s you! It’s the Alice I’ve known and loved all these years, who was getting buried under a layer of fat and misery.”

“I wasn’t miserable.” I frowned.

“Oh, pooh,” Maggie said. “How could you not have been miserable? Your husband was never around, your daughter was growing up and leaving home, your mother was fading away, you had nothing to do—”

I felt stung. “I had the house to take care of,” I said. “My mother to look after. And just because Diana was theoretically grown up and away at college didn’t mean she didn’t need me anymore.”

“I know,” Maggie soothed. “I don’t mean to denigrate all you did. What I’m trying to get you to see is how much lighter you look now. How much younger.”

“Younger?” I said, focusing again on my reflection.

“It’s partly the weight,” Maggie said meditatively, staring at my image in the mirror, “but it’s something else too, some burden that seems to have been lifted. Besides, you always looked a lot younger than you really were. Don’t you remember when we were seniors in high school, you were the only one who could still get into the movies for the kids’ price? And even when you were in your thirties, long after you had Diana, you’d still get carded in bars.”

“I don’t think I’d get carded now.”

“Maybe not, but you could look a lot younger than you are. A lot younger than you do.”

“What do you mean?”

“I mean that with some color in your hair, a little makeup, some clothes that fit, for God’s sake, you could still look like you were in your twenties!” Maggie exploded. “That’s why I dragged you out of that fucking voodoo parlor! We’re the only ones who have the power to turn our dreams into reality.”

I smirked at Maggie. She was usually the first one to puncture what she called “that power-of-positive-thinking bullshit.” I was the one who made wishes on stars and birthday candles, who believed, as Cinderella said in the Disney movie I’d watched at least two hundred times with Diana nestled into my side, that “if you dream a thing more than once, it’s sure to come true.” But now instead of smirking back, Maggie only gazed at me with a look of utter conviction.

“So you think,” I said finally, “that I have the power to make myself younger just by wishing it were so?”

“Not just by wishing,” she said. “We’re going to need a little help from Clairol. Let’s get started.”

* * *

It was while I was sitting on the purple chaise, munching on a cold slice of pizza that was going to have to count for dinner, with a garbage bag knotted over the chemical glop on my hair, that Maggie told me about her dream. She wanted to have a baby.

“You’re kidding,” I said, trying to keep my mouth from falling open.

She looked insulted. So insulted that it was clear this was anything but a joke. It was just that I’d known Maggie as long as I could remember, and she’d never had the least interest in children or motherhood. When I was rocking my baby dolls and tucking in my stuffed animals, Maggie was crouched on the floor, trying a new finger-painting technique. When I was eagerly babysitting to earn extra money, Maggie was mowing lawns, helping people clean out their attics—anything to get out of helping take care of her seven younger brothers and sisters. She always said that growing up, she’d changed enough diapers to last a lifetime.

And now here she was, at forty-four, suddenly changing her mind.

“What happened?” I said.

“Nothing happened. I guess I finally decided that I’d been a kid for long enough. I’m ready to grow up and be the parent now.”

“But a baby,” I said. Living in the suburbs, I was around mothers and babies all the time—the kids in the house behind me, screaming all day and night; the young moms in the supermarket, struggling to keep their squirming toddlers in the grocery carts. After all my years of wishing for and dreaming of having another baby, of looking at pregnant women and mothers with infants with a level of envy and longing that could literally make me double over, I had finally passed into some other stage where I thought babies, like tiger or bear cubs, were adorable but frightening, best viewed from a distance. Through glass.

I struggled for a way to convey my misgivings to Maggie without coming straight out and telling her I thought having a baby at this age, after an entire adulthood of independence, was the worst idea she’d had since shaving her head.

I took Maggie’s hand, rough as a carpenter’s from years of twisting wire into roundness.

“You know,” I said, in the gentlest voice I could summon, “it’s so much work having a baby, especially on your own. Waking up in the middle of the night, carrying the stroller up and down the stairs, the diapers, the crying—”

“I grew up with that, remember?” Maggie snapped, snatching back her hand.

“Exactly!” I said. “But you were helping out your mom then; it wasn’t all on your shoulders. You live in this neighborhood where almost nobody has kids, none of your friends have kids, your life is in no way set up for it. And it’s not just having a baby—you’ve got the nursery school search ahead, tuition payments, adolescence. When the kid’s out of college, you’d be collecting social security.”

“That’s it, isn’t it?” Maggie said stonily. “You think I’m too old.”

“You are too old!” I exploded. “We’re both too old!”

“I thought that you, of all people, would understand my desire for a child,” Maggie said, blinking back tears, “after all you went through to have Diana, after all the years you tried to have another baby.”

I softened, remembering how powerful my own yearning had been. But I also remembered how completely a baby, even the quest to have a baby, could take over your life; how exhausting parenthood could be even when you were twenty years younger than Maggie and I were now.

“I do understand,” I told her, trying to take her hand again. “But sometimes you reach a point in life where you’ve just got to leave something behind. When it’s just too late.”

I knew that was harsh, as Diana would say. But Maggie and I had vowed, way back in fourth grade, to always tell each other the Bottom Line Truth—the BLT—even when we knew the other person didn’t want to hear it. She had to

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...