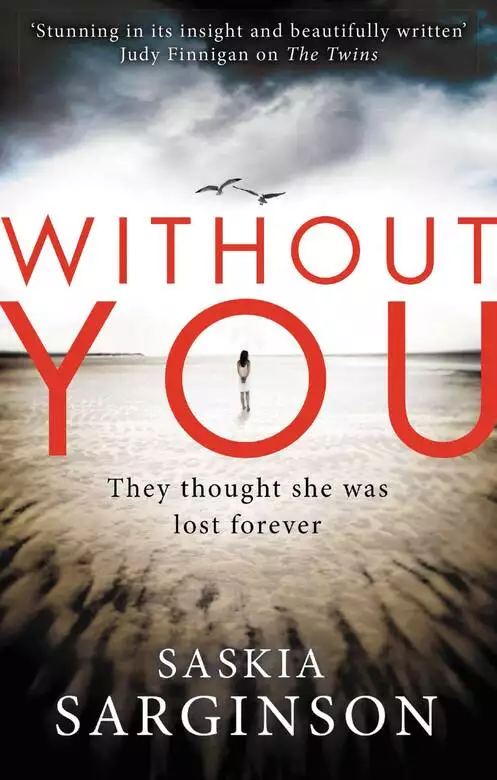

Without You

- eBook

- Paperback

- Audiobook

- Hardcover

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

1984, Suffolk. When 17-year-old Eva goes missing at sea, everyone except her younger sister presumes that she drowned. Faith refuses to consider a life without Eva; she's determined to find her sister and bring her home alive. Close to the shore looms a mysterious island, dotted with windowless concrete huts. What nobody knows is that inside one of the huts Eva is being held captive. That she is fighting to survive- and to return home.

Release date: June 10, 2014

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Without You

Saskia Sarginson

There are boys fishing for crabs off the quay. I stop dead in the sunshine, blinking and uncertain. Then it’s OK because it’s nobody I know. Just townie kids here for the summer holidays. They’re squatting next to buckets, poking at crabs they’ve caught on lines baited with bacon rind, strangers with pale skin and funny accents.

It’s low tide, so I sit on the end of the quay, swinging my legs over the edge. There’s only a couple of feet of water around the slimy wooden base, clumps of brown bladderwrack tangling under the surface. Even if I was stupid enough to fall in, I’d be able to stand up, my toes squelching in the mud. It’s already hot. The sky is clear, and there’s a breeze strong enough to set masts clanking. Seagulls hover overhead, alien eyes swivelling for scraps of bacon fat, wings bright against the sun.

Ted, the quay master, walks by with a coil of rope over his shoulder and ruffles my hair with his thick hand. ‘Not crabbing today, Faith, eh?’ he says in a normal, friendly voice, but the look he gives me is like all the other adults’–full of pity for the little girl with the drowned sister. I concentrate on watching a plump boy hauling up his line, hand over careful hand, leaning over to see if he’s caught anything. There is a barnacled crab at the end, hanging onto the bacon with pincer claws. Just as the boy is about to reach out and grab it, the crab falls with a splash. Crabs that have been caught before know exactly when to let go, escaping with shreds caught in their cunning jaws. I watch the boy’s face, how his mouth droops and his cheeks redden. He scowls at me.

I shut my eyes with a snap and turn away, telling myself to ignore him: sticks and stones. I begin to hum under my breath. Hello Dolly, you’re still glowin’, you’re still crowin’, you’re still goin’ strong…

The boats on the river flit past on gusts of wind. Red, white and brown sails flapping. It used to be Dad and Eva out there. You could hear him shouting from the shore. Mum said it was embarrassing. Dad has always had a temper. In a boat he was worse. Eva ignored him or shouted back, standing up to her knees in the river, Dad struggling with the ropes–‘Keep her steady, damn it!’ But then they’d go off and by the time they came back, wind-blown and red-cheeked, they were smiley and pleased with themselves, talking about how they went past the island and out to sea.

Dad hasn’t lost his temper since the accident. He can’t remember what happened the day that he and Eva sailed into the storm. The boat capsized and Dad lost consciousness. He was fished out of the water by the coastguard but they never found my sister. The doctor says Dad’s put up barriers in his mind and I know that Mum is angry with him for keeping the barriers there when there are so many questions to answer. Eva’s lifejacket was found floating in the waves. Mum keeps asking why he let Eva sail without it and Dad swears that she must have been wearing it. Dad has sold the boats, says he’ll never sail again. I don’t mind. I’m not a sailor. Capsizing was the worst. But they were Eva’s boats too.

Still humming, I shade my eyes to stare at the island. It lies beyond the mouth of the river, about half a mile offshore. A long time ago it was connected to a spit of land that runs along the other side of the river. But tides and waves have worn the spit away. Without the boats, without my sister, there’s no way I can go back there. It’s private, out of bounds. When Eva and I landed we had to do it in secret. The island squats on the horizon, the pagodas sticking up like weird chimneys. I screw up my eyes against the glare and think about the last time I was there with her.

The boat flew over the water’s surface, spray kicking up under the prow. Stars rose from the glittering river to break against my gaze. The sail strained, fat with wind. Eva, sitting at the tiller behind me, was already ducking her head ready for the swing of the boom.

‘Hey Shrimp, going about!’ she yelled and I released the jib. The dinghy turned and slowed inside the choppy waves. Then with a snap, the wind caught the sail again. I yanked as hard as I could, my fingers tight around wet rope and we were flying across the water towards the island. I wasn’t frightened in a boat with Eva. She’s a good sailor.

We sailed onto the gravelly beach. The boat made a crunching noise, stones grating against the hull, scraping the paint. Eva winced. Dad would be furious. We left the boat half-hidden, pulled up on the shingle, with a big stone over the anchor to keep her safe.

‘Race you to the other side!’ Eva called. It wasn’t a fair race. She’s seven years older than me and her legs are twice as long as mine. I followed her, slipping on mud, splashing through shallow rivulets and puddles. I was glad to be on land again, relieved by the feel of earth under my feet. The island slopes up from the shore, becoming stony and dry. Gorse bushes cling, withered and stunted, to the pebbly, windswept crest. And then the land falls away and there is nothing but the grey North Sea, seagulls wheeling and crying as if they’re flying over the edge of the world.

Stripping off her shirt and jeans, Eva threw herself into the waves in her knickers and bra. I sat on the steep bank of pebbles, watching. I can’t swim properly. I can manage a doggy-paddle if I have to, swimming with my head clear of the water, mouth open to gasp air. I’m frightened by the waves. Whenever I wade into the sea, they push me over and drag me across sharp stones, splashing salt into my eyes, knocking the breath out of my lungs. I come out covered in bruises. I hate getting wet as much as I hate being cold.

‘You’ve got to stop being a wimp!’ Eva shouted. ‘There’s nothing to be frightened of. Just let yourself float. Let the waves do the work for you.’

She couldn’t understand what it was like to be afraid of the currents or unseen fish slipping past her legs, or a wave taking her out to sea. When I was a baby, they put a lifejacket on me and tied a rope around my waist, letting me bob up and down at the end of the tether, believing that I’d learn to swim like Eva had. But I didn’t. I screamed and cried until Mum or Dad hauled me onto dry land, blotting the wet from my face, frowning at me anxiously.

I shivered, watching Eva swim back and forth, battling through the big brown waves. Her arms gleamed as they powered up and over her head, pulling her along. She only swam for a little while. It was too cold, even for her. When she was swimming, her movements were exact and elegant, but it’s impossible to walk on shingle barefoot with any dignity and it made me laugh the way she staggered out, hobbling and wincing over the stones, limbs jerking like a rag-doll. To pay me back she flicked water from her dark hair at me as she knelt down, panting, her clothes in her arms. I could feel her energy, bright as the drops of moisture on her skin. Eva seems more alive than other people.

She lay back on her elbows. It was just the two of us on the long deserted beach, as if we were the only ones left on a planet made of shingle, sea and sky.

‘What a mess,’ Eva was saying, gazing at the rubbish that had been thrown overboard: plastic bottles, yoghurt pots, corks and bits of rope and odd shoes caught up in twists of seaweed and driftwood at the tide-line. ‘Honestly–sometimes I wonder why we love it so much.’

I followed her gaze. Sometimes really disgusting things like Tampax or nappies got washed up on the beach. But I couldn’t see anything revolting. She’d taken a cigarette out of her jacket pocket and lit it with difficulty, cupping her hands around the match and turning her head away from the wind. Her fingers were pink-tipped and puckered by seawater. Inhaling deeply, she sighed. ‘Maybe ’cos it belongs to us.’

The island didn’t belong to us. It belonged to the Ministry of Defence. It still does. We were trespassing. Half the island is fenced off by trailing wire and ruined by derelict huts, crumbling roads, rolls of razor wire and the concrete pagodas. People say they were laboratories, used for atomic-weapon research. The project’s been abandoned and the buildings lie empty and forbidden. I don’t like them, especially the pagodas. It feels as though things inside watch you, although there are no windows. Blank walls stare. Eva’s smoke made my nose itch. I turned my head away. She would be in trouble if Mum and Dad knew.

‘Actually, nobody should own this place,’ she continued, ‘not even us. It’s too wild to belong to anyone, isn’t it?’

I lay on my front on the stones, turning my head to look at her. She wasn’t bothering to dry herself or get dressed, even though her lips were violet with cold and her skin prickled with goose bumps. Her knickers had ‘Monday’ appliquéd onto them. She had all the days of the week, wearing them at the wrong times. Her attention seemed to be on the slow movement of the cigarette to her lips, and the lazy drift of smoke out of her half-open mouth. She was practising her technique.

‘Watch out for the oil.’ Eva nodded to a sticky patch oozing over the stones as she stubbed the cigarette out on a bit of driftwood. I moved my hand. My warts looked worse in the sunlight. I got my first one when I was five. A lump that grew on my knee after I’d grazed the skin. More came, like mushrooms sprouting overnight on my knees and hands. I hate them.

She pulled on her clothes and we started to make our way across to the far tip of the island, to where the seals basked. There was a dead fox near the gorse bushes and I squatted to examine the way his fur had come away in chunks, exposing rotting flesh. You could see the white of his bones pushing through, like the wreck of a ship surfacing. There were living things writhing inside him. They’d already eaten his eyes. Soon it would be picked clean. I wondered if I came back in a couple of weeks whether I could persuade Eva to let me take his skull home.

‘God!’ Eva turned away, putting her hands over her face. ‘It stinks!’

Better to swallow this dead-fox smell, I thought, than nicotine fumes. Eva had changed. Her new interest in boys and cigarettes and parties blotted out other parts of her, making her behave like an idiot. She pretended she was afraid of spiders and dead foxes.

‘Guess what?’ she asked as we walked through the samphire towards the point. ‘I’ve met someone.’

I was silent. The gulls were swooping low over the river and the tide was going out, boats turning the other way on their moorings.

‘He’s… different,’ she continued. ‘He’s really cool. Cooler than any of the boys around here.’ She examined her nails and glanced at me sideways so that I was flattered that she wanted to confide in me.

I scratched around in my head for the right question. ‘Where did you meet him?’

She grinned. ‘A club. In Ipswich. Mum and Dad thought I was staying with Lucy. He’s from London. He’s even lived in America. He’s a musician. He’s into gothic stuff.’ She flushed and nodded as if this was important information. ‘He’s called Marco. I’m not going to tell Mum and Dad about him. They won’t like him, just because he’s older than me, and he’s got a tattoo and dyes his hair black. His parents moved to Ipswich, but he hates it here; he’s planning to go back to London.’

Thinking about him seemed to put her into a trance. She tipped her head back, squinting into the sky. ‘The way he makes me feel… I don’t know. It’s like being drunk without drinking,’ she said in a low voice. ‘It makes me feel like anything could happen. Anything at all.’ She grabbed my hands and began to dance the polka, ‘One, two, hop and turn,’ across the stones; and I was caught up in the whirling movement, stumbling and turning with our hair flying out behind us. Her fingers gripped hard. The sky and the beach blurred into a Catherine Wheel of blues and greens. And we were in the centre of it–the bright, turning centre. My stomach lurched as we danced faster, my head reeling with dizziness. Breathless, we broke apart, falling back onto the shingle. ‘Maybe I’m in love,’ she said.

We lay panting, spread-eagled, gazing at shreds of cloud floating past, and the wheeling birds making shapes against the sun. I wondered what Eva and I would look like from up there, through a seagull’s eyes, imagining us as fixed dots inside the hard shine of its stare. Eva clambered back onto her feet when the beach stopped spinning, hauling me up. A few moments later we’d reached the point, and I could see fat bodies on the mud. ‘Seals,’ I mouthed, pointing, and she winked.

Eva stopped. Her hair, dry now from the wind, blew in curls across her face. She looked serious. ‘Promise on your life that you won’t tell Mum and Dad about Marco.’

She spat into her hand, a splatter of slimy bubbles, and put it out for me to shake. We locked fingers and I felt the wet of her spit.

Dropping onto all fours, we crawled quietly through the bushy green, sharp pebbles biting into palms and knees. The wind was blowing towards us so we were able to get close enough to the seals to see their noses framed by whiskers like over-sized cats. Their eyes looked as though they were filled with tears.

‘Selkies,’ Eva murmured.

‘Do you think all of them are, or just some?’

‘Ah, well, we can’t know that,’ she whispered. ‘It’s only at night that the seals shed their skins and become human.’

I’d heard this story lots of times. But I never tired of it.

‘And then they become women,’ her voice was dreamy, ‘slipping out of their seal form, and dancing on the beach all night with their webbed toes. If one of them falls in love with a mortal, some handsome fisherman maybe, then she’ll give up her seal shape and live as a woman.’ Eva smiled at me. ‘But her husband will have to hide her seal skin, or the sea will call her back.’

‘We should come at night,’ I suggested, excited by the idea, ‘sail over to see them.’

‘Are you brave enough?’ She tilted her chin. ‘We’d have to be careful not to be caught by the selkies, or by them…’ She jerked her head in the direction of the windowless concrete pagodas. ‘God knows what crawls out of those places.’

I shivered in the sun. Eva’s eyes were liquorice dark, just as I imagined a selkie’s would be. Her fingers brushed against mine and she took my hand and squeezed it. She didn’t mind my warts. Her head touched mine and I smelt nicotine in her hair and the tang of the sea.

I miss her.

I miss her even though she’d do her big-sister act of slamming doors in my face and telling me to piss off. Once she locked me in the cupboard on the landing for an hour. But Eva’s bedroom feels lonely without her, without her clashing perfumes, tantrums and dance routines, Police and Culture Club turned up too loud on the radio.

She’s been gone for three months.

A few days before the accident, I walked in to find her kneeling by her dressing table, hands clasped tightly in prayer. She’d closed her eyes. Anything, I heard her beg, I’ll do anything if you let me not have a spot this weekend.

I snorted, clasping my hand over my mouth. Eva threw a hairbrush at my head. It missed. She’s rubbish at over-arm.

‘I don’t think God cares if you get a spot,’ I said, picking up the hairbrush. ‘Hasn’t he got wars and starving babies to worry about?’

‘Warts?’ she exclaimed, eyes round.

‘No…’ I began to explain, but she’d already forgotten me.

Mum says one day I’ll wake up and my warts will be gone. Until that happens, I keep my sleeves pulled down. I thought Eva might lose interest in her mirror and speak to me. I’d lingered in her doorway, the frayed cuffs clasped between my fingers, loose threads tickling my skin. But she only gave me an impatient glance.

I don’t know why Eva kept checking her reflection. It stayed the same. She has a wide mouth in a square jaw and sloping cheekbones, slanted as a cat’s. She glows a kind of dark gold, her skin shiny as polished amber. My complexion is thin and white as a piece of paper.

At first Mum wouldn’t even pick up the tangle of dirty clothes lying on Eva’s bedroom floor, although later they ended up clean and ironed and folded in Eva’s drawers. I go in there and stroke her ornaments, her china rabbits and the desert rose; sometimes I try on her string of water pearls. They gleam in my hands, and they seem to hold the warmth of Eva’s skin. If I crumple her clothes into a ball and push my nose into the folds, I can still smell her. Once when I pulled her nightdress from under her pillow, I found one of her dark hairs stuck to the fabric.

I hate it when people talk about her because they use a special hushed voice, as if they’re in church. They say she was this; she did that. But she didn’t drown, I tell them. They shake their heads, and give me worried smiles, glancing away, embarrassed.

She’s not dead. Not like Granny Gale, cold in a box under the churchyard. I miss Granny too. She used to live in a caravan in our garden. Missing her is a low ache inside my bones. The thing is, she was very old and she wasn’t afraid to die. She told me that she’d been blessed to find love at her age, ‘After more than forty years of being alone, imagine that,’ she said. ‘But nothing lasts for ever, darling. The curtain always comes down when the show’s over.’ Eva is too young to die. She’s only seventeen and she’s lost inside deep water, far from the surface, far from human voices. Missing Eva is a sharp pain that makes my heart beat too fast.

There are creatures in the sea: ancient things, beyond imagination and knowledge, unseen by people. When they looked up through the waves and saw Eva’s black curls and golden skin with no spots, they must have fallen in love, like a selkie catching sight of a fisherman. Everyone fancies my sister. The boys that hung around at the village bus stop called after her, letting out long whistles, and scratching her name onto the wood of the shelter with their penknives. Robert Smith followed her home from school. He hung around behind the hundred-year-old oak across the road, peering up at her window. I looked under the tree after he’d gone and there was a mess of fag ends and a hard pink ball of chewed gum. ‘Pervert,’ she said when I told her he was there. But she was laughing.

‘Don’t let it go to your head,’ Granny Gale warned when Eva got five Valentine’s cards. I didn’t get any, except the one that Mum sent. She put it through the letterbox but she forgot to put a stamp on it, so I knew it was from her. Dad told Eva that she was too young for boyfriends. They argued about how many evenings she was allowed out a week and what time she could get back. ‘It’s like living in a prison!’ she’d yell. And Dad kept telling her that if she worked hard at school she’d give herself choices, would make her world bigger. ‘You’ve got the rest of your life for boys,’ he said.

Dad’s nickname for Eva was ‘Duchess’. It was supposed to be a joke, because of her airs and graces; but Eva had a way of walking, as if there was a pile of books balanced on her head, and a habit of tossing her hair when she was annoyed, that made you imagine her in a long, swishy dress with servants scurrying behind.

The coastguard worked for thirty hours before calling off the search. There was a helicopter and boats. A month afterwards, Mum and Dad held a memorial service for her. The church was packed–people standing in the graveyard sobbing, trying to sing hymns with shaky voices. O Christ! Whose voice the waters heard, and hushed their raging at thy Word. The vicar talking about Eva from the pulpit: the tragedy of her short life. Other people getting up to read poems and tell stories about her, stopping to blow their noses, wiping their eyes. They didn’t seem to be talking about my sister. It was as if she’d been too good to be true–like a saint. I stood in the pew at the front between Mum and Dad, unable to sing, the closed hymn book clutched in my hands, white flowers glowing in the dim light, shedding their sickly scent.

Eva, if you can hear me, I hope that you aren’t cold and lonely. You must miss Mum and Dad, your Topshop jeans and your old teddy. I want you to know that I haven’t given up on you. And I’m sorry for using your lipstick and drawing with it so that the end squished down into a stub. I love you, Eva. I will find a way to bring you back.

He didn’t tell me his name for a long time. But one morning he said that it was Billy. It sounds soft and harmless in my mouth, a lilting whisper, two syllables like a bird-call. I told him my name at the beginning, because I remembered hearing somewhere that it’s important to become a real person, to make your kidnapper see you as human. But he keeps calling me ‘girl’.

Coughing up my guts on the beach, lungs on fire, I couldn’t see who crouched over me. I was confused and weak and he was just a blurry outline, dark against dark. He hoisted me into his arms, carrying me like a baby. He was panting, struggling to hold me, his feet working inside the crunch of pebbles. I was jolted, my head bumping against his shoulder as he scrambled up a steep, crumbling slope. There was the slide and clatter of stones under us. And then more walking–this time on a flat surface. We entered a building, so black that it seemed as though I’d been blindfolded. He laid me down on the ground: fabric at my chin, a scratchy blanket itching me, rough against my face. I smelt musty air, and I remember thinking that I should ask where Dad was, and if he was all right, but I didn’t have the strength.

When I woke in the dim wash of early morning, I thought I could hear the sea. I looked around, turning my neck gingerly to take in the windowless peeling walls. My head felt heavy, bruised. The waves seemed to be inside my skull, pounding against my brain. I stared, puzzled, at frayed and severed wires hanging loose and a grid of corroded pipes under the vaulted roof. It was some kind of derelict shelter. I felt a tick of fear. I knew that I should be at home or even in hospital and that this wasn’t right. My breathing came fast and shallow. I moved parched lips and swollen tongue, trying to find words to ask for help, to find out where I was, to call for Dad.

A faceless creature loomed. His palm sealed my mouth, the pressure of his fingers stopping my scream. I stared into a pair of grey eyes, expressionless as stones. The rest of his face was wrapped in a blue woollen scarf. I shrank inwards, as if I could hide inside my skin, shrivelling inside damp clothes. ‘Awake then?’ The voice sounded low, muffled by folds of fabric. ‘You thirsty?’

It was then that I realised my wrists were tied.

He doesn’t bother with the scarf anymore. He doesn’t need to. His hair obliterates most of his face. He has a thick, brown beard and moustache and matted, shaggy hair that falls into his eyes. I hate it when he gets close and I smell the unwashed stink. It makes me want to gag.

‘Time to go in the hole.’ He nods towards the crater in the floor. ‘I’ve got to get provisions.’

‘No.’ My toes clench with resistance, my heart beating fast. ‘I won’t run away.’ I’ve taken on the pleading tone that I despise. ‘Please don’t leave me down there…’

‘Nah,’ he shakes his head, a sly smile as if he’s amused, ‘you’ve tried it too many times. Come here.’

He has rope in his hands, a thick coil. I’ve backed into a corner. A broken metal rod sticking out of the wall pokes my back. There is no point trying to fight him, trying to struggle. Under the beard and the filthy clothes, he’s young and strong, taller than me. Maybe even as tall as Dad. He carries a knife at his belt. He told me that he used to be a soldier; he’s been trained to kill people. He has killed people. When I tried to slip past him before, he got my arm behind my back and the blade against my neck in one slick movement, pressing the sharp point into my skin, so that I felt my blood pulsing against it.

I wait in the corner. I’ve got nowhere to go. He’s too fast for me. ‘Please.’ I try to sound reasonable, but my voice is a hoarse whisper. ‘Please, Billy.’

He jolts when he hears his name. With a quick mutter, head down, he grabs my wrists. He secures the rope around my waist and then his own. Bracing himself, he nods to me, telling me that I should step backwards off the edge, so that he can lower me into the pit. Billy says that it was used for storing atom bombs. We are in one of the concrete pagodas on the island. Once I’d worked it out, I could see that the high vaulted roof with the glassless gaps between pillars, the odd metal casings and derelict equipment all made sense.

Whenever Faith and I came to the island, it never occurred to us to go inside them. There are warning notices next to the lines of barbed wire telling people to keep out–to stay away from the unexploded landmines hidden under the pebbles in that half of the island. And I knew what the interior of the pagodas had been used for, so I suppose I’d thought the air would be tainted, poisoned by the fumes from bomb experiments.

My feet slip against the concrete wall; the rope digs into my waist. I hold onto the hairy, coarse twist of it tightly with both hands. It’s about a ten-foot drop below me. Bruising my knees, scrabbling for control, I abseil slowly into the dank hole. As soon as I’m standing on the bottom, Billy indicates that I untie the rope so that he can pull it up. He throws down a plastic bottle of water.

I am rigid with a familiar fear. The tall, steep sides are scratched and pockmarked. They hold darkening shadows, heavy with stale air. There is nothing down here except rusting tin cans, bottle tops and broken glass, bits of screwed up paper and a three-legged chair that the army must have left behind. Far above me I can hear Billy moving about, and then his footsteps as he leaves. He calls back, ‘Won’t be long. Don’t go anywhere.’

They are new, these unexpected flashes of humour. They’re cruel, I suppose, sarcastic, but it’s an improvement. The first time he left me here he didn’t say anything. I’d struggled against him when I realised that he’d wanted to put me in the crater. He’d bruised my arms forcing me in. I’d stumbled, swinging from the rope onto the bottom of the pit, scraping my cheek against the rough sides. Staring up at him, I’d been certain that he was going to pull out a gun. I’d closed my eyes. Numb. Cold. There was nowhere to run. Nowhere to hide. Against my shuttered lids I’d seen flash after flash of snatched memory, a lifetime passing in the gabble of a speeded-up film. When I’d opened my eyes, he’d gone. I realised then that he could kill me without pulling a trigger. All he has to do is leave me here.

Even now that I know I won’t be in the pit for more than a couple of hours, it’s still unbearable. It smells of old urine and metal. Claustrophobia presses in, and it feels as though the narrow space is shrinking, the walls leaning in closer, squeezing the life out of me. Panic that something will happen to him and I’ll be left here for ever scrabbles inside. Nothing will make it go away. I feel sick with anxiety. The helplessness of it carves out a hollow in my stomach. I crouch on rubbish, my back resting against the wall and close my eyes. I can hear the faint wash of the sea, looping cries of seagulls as they fly above the flat roof of the pagoda. Sometimes a bird will get in. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...