1

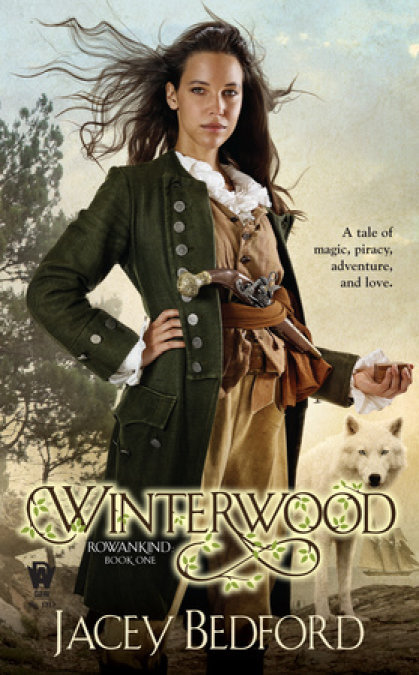

A Bitter Farewell

April 1800, Plymouth, England

THE STUFFY BEDROOM STANK OF SICKNESS, with an underlying taint of old lady, stale urine, and unwashed clothes, poorly disguised with attar of roses. I’d never thought to return to Plymouth, to the house I’d once called home; a house with memories so bitter that I’d tried to scour them from my mind with saltwater and blood.

Had something in my own magic drawn me back? I didn’t know why it should, though it still had the capacity to surprise me. I could control it at sea, but on land it gnawed at my insides. Even here, less than a mile from the harbor, power pulsed through my veins, heating my blood. I needed to take ship soon, before I lost control.

Little wonder that I’d felt no need to return home since eloping with Will.

My ears adjusted to the muffled street sounds, my eyes to the curtained gloom. I began to pick out familiar shapes in the shadows, each one bringing back a memory, all of them painful. The dressing table with its monstrously carved lion mask and paw feet where I had once sat and experimented with my mother’s face powder and patches, earning a beating with the back of a hairbrush for the mess. The tall bed—a mountain to a small child—upon which I had first seen the tiny, shawl-wrapped form of my brother, Philip, the new son and heir, pride and joy, in my mother’s arms.

And there was the ornate screen I’d once hidden behind, trapped accidentally in some small mischief, to witness a larger mischief when my mother took Larien, our rowankind bondsman, to her lonely bed. I hadn’t understood, then, what was happening beneath the covers, but I’d instinctively known that I should not be there, so I’d swallowed my puzzlement and kept silent.

Now, the heaped covers on that same bed stirred and shifted.

“Philip?” Her voice trembled and her hand fluttered to her breast. “Am I dreaming?”

My stomach churned and my magic flared. I swallowed hard, pushed it down and did my best to keep my voice low and level. “No, Mother, it’s me.”

“Rossalinde? Good God! Dressed like a man! You never had a sense of decorum.”

It wasn’t a question of decorum. It was my armor. I wore the persona as well as the clothes.

“Don’t just stand there, come closer.” My mother beckoned me into the gloom. “Help me up.”

She had no expectation that I would disobey, so I didn’t. I put my right arm under hers and my left arm around her frail shoulders and eased her into a sitting position, hearing her sharp indrawn gasp as I moved her. I plumped up pillows, stepped back and turned away, needing the distance.

I twitched the curtain back from the sash window an inch or two to check that the street outside was still empty, listening hard for any sound of disturbance in the normality of Twiling Avenue—a disturbance that might indicate a hue and cry heading in my direction. I’d crept into the house via a back entrance through the next-door neighbor’s shrubbery. The hedge surrounding the house across the street rippled as if a bird had fled its shelter. I waited to see if there was any further movement, but there wasn’t. So far there was nothing beyond the faint cries of the vendors in the market two streets over and the raucous clamor of the wheeling gulls overhead.

Satisfied that I was safe for now, I turned back to find my mother had closed her eyes for a moment. She snatched a series of shallow breaths before she gave one long sigh. Opening her eyes again, she regarded me long and steady. “Life as a pirate’s whore certainly seems to suit you.”

“Yes, Mother.” Pirate’s whore! I pressed my lips together. It wasn’t worth arguing. She was wrong on both counts, pirate and whore. As privateers, we cruised under letters of marque from Mad King George for prizes of French merchantmen, Bonaparte’s supply vessels. As to the whore part, Will and I had married almost seven years ago.

“So you finally risked your neck to come and say good-bye. I wondered how long it would take. You’re almost too late.”

I didn’t answer.

“Oh, come on, girl, don’t beat about the bush. My belly’s swollen tight as a football. This damn growth is sucking the life out of me. Does it make you happy to see me like this? Do you think I deserve it?”

I shook my head, only half-sure I meant it. Damn her! She still had me where it hurt. I’d come to dance on her grave and found it empty.

“What’s the matter?”

I waited for “Cat got your tongue?” but it didn’t come.

“Give me some light, girl.”

I went to open the curtains.

“No, keep the day away. Lamplight’s kinder.”

I could have brightened the room with magic, but magic—specifically my use of it—had driven a wedge between us. She had wanted a world of safety and comfort with the only serious concerns being those of fashion and taste, acceptable manners and suitable suitors. Instead she’d been faced with my unacceptable talents.

I struck a phosphor match from the inlaid silver box on the table, lifted the lamp glass and lit the wick. It guttered and smoked like cheap penny whale oil. My mother’s standards were slipping.

I took a deep breath; then, to show that she didn’t have complete control of the proceedings, I flopped down into the chair beside the bed, trying to look more casual than I felt.

Her iron-gray hair was not many shades lighter than when I’d last seen her seven years ago. Her skin was pale and translucent, but still unblemished. She’d always had good skin, my mother: still tight at fifty, as mine would probably be if the wind and the salt didn’t ruin it, or if the Mysterium didn’t hang me for a witch first.

She caught me studying her. “You really didn’t expect to see me alive, did you?”

I shrugged. I hadn’t known what to expect.

“But you came all the same.”

“I had to.” I still wasn’t sure why.

“Yes, you did.” She smirked. “Did you think to pick over my bones and see what I’d left you in my will?”

No, old woman, to confront you one last time and see if you still had the same effect on me. I cleared my throat. “I don’t want your money.”

“Good, because I have none.” She pushed herself forward off her pillows with one elbow. “Every last penny from your father’s investments has gone to pay the bills. I’ve had to sell the plate and my jewelry, such as it was. All that’s left is show. This disease has saved me from the workhouse.” She sank back. “Don’t say you’re sorry.”

“I won’t because I’m not.”

Leaving had been the best thing I’d ever done.

Life with Will had been infinitely more tender than it had ever been at home. I didn’t regret a minute of it. I wished there had been more.

The harridan regarded me through half-closed eyes. “And have I got any by-blow grandchildren I should know about?”

“No.” There had been one, born early, but the little mite had not lasted beyond his second day. She didn’t need to know that.

“Not up to it, is he, this Redbeard of yours? Or have you unmanned him with your witchcraft?”

I ignored her taunts. “What do you want, forgiveness? Reconciliation?”

“What do I want?” She screwed her face up in the semblance of a laugh, but it turned to a grimace.

“You nearly got us killed, Mother, or have you conveniently forgotten?”

“That murdering thief took all I had in the world.”

All she had in the world? Ha! That would be the ship she was talking about, not me.

“That murdering thief, as you put it, saved my life.”

And my soul and my sanity, but I didn’t tell her that. He’d taught me to be a man by day and a woman by night, to use a sword and pistol, and to captain a ship. He’d been my love, my strength and my mentor. Since his death I’d been Captain Redbeard Tremayne in his stead—three years a privateer captain in my own right.

“Is he with you now?”

“He’s always with me.”

That wasn’t a lie. Will showed up at the most unlikely times, sometimes as nothing more than a whisper on the wind.

“So you only came to gloat and to see what was left.”

“I don’t want anything of yours. I never did.”

“Oh, don’t worry, what’s coming to you is not mine. I’m only passing it on—one final obligation to the past.” Her voice, still sharp, caught in her throat and she coughed.

“Do you want a drink?” I asked, suddenly seeing her as a lonely and sick old woman.

“I want nothing from you.” She screwed up her eyes. Her hand went to her belly. I could only stand by while she struggled against whatever pain wracked her body.

Finally she spoke again. “In the chest at the foot of the bed, below the sheet.”

I knelt and ran my fingers across it. It had been my father’s first sea chest, oak with a tarnished brass binding. I let my fingers linger over his initials burnt into the top. He’d been an absentee father, always away on one long voyage after the other, but I’d loved his homecomings, the feel of his scratchy beard on my cheek as he hugged me to him, the smell of the salt sea and pipe tobacco, the presents, small but thoughtful: a tortoiseshell comb, a silken scarf, a bracelet of bright beads from far-off Africa.

I pulled open the catch and lifted the lid.

“Don’t disturb things. Feel beneath the left-hand edge.”

I slid my hand under the folded linen. My fingers touched something smooth and cool. I felt the snap and fizz of magic and jerked back, but it was too late, the thing, whatever it was, had already tasted me. Damn my mother. What had she done?

I drew the object out to look and found it to be a small, polished wooden box, not much deeper than my thumb. I’d never seen its like before, but I’d heard winterwood described and knew full well what it was. The grain held a rainbow, from the gold of oak to the rich red of mahogany, shot through with ebony hues. It sat comfortably in the palm of my hand, so finely crafted that it was almost seamless. My magic rose up to meet it.

I tried the lid. “It’s locked.”

She had an odd expression on her face.

“Is this some kind of riddle?” I asked.

“Your inheritance.”

“How does it open? What’s inside it?”

“That’s for you to find out. I never wanted any of it.”

My head was full of questions. My mother hated magic, even the sleight-of-hand tricks of street illusionists. How could this be any inheritance of mine?

Yet I could feel that it was.

I turned the box around in my hands. There was something trapped inside that wanted its freedom. No point in asking if anyone had tried to saw it open. You don’t work ensorcelled winterwood with human tools.

Wrapping both hands around the box, I could feel it was alive with promise. It didn’t seem to have a taint of the black about it, but it didn’t have to be dark magic to be dangerous.

I shuddered. “I don’t want it.”

“It’s yours now. You’ve touched it. I’ve never handled it without gloves.”

“Where did it come from?”

She shook her head. “Family.”

“Neither you nor Father ever mentioned family, not even my grandparents.”

“Long gone, all of them. Gone and forgotten.”

“I don’t even know their names.”

“And better that way. We left all that behind us. We started afresh, Teague and I, making our own place in society. It wasn’t easy even in this tarry-trousers town. Your ancestors companied with royalty, you know, though much good it did them in the end. You’re a lady, Rossalinde, not a hoyden.” She winced, but whether from the memories or the pain I couldn’t tell. “That blasted thing is all that’s left of the past. It followed me, but it’s too much to . . .” Her voice trailed off, but then she rallied. “I wasn’t having any of it. It’s your responsibility now. I meant to give it to you when you came of age.” She narrowed her eyes and glared at me. “How old are you, anyway?”

I was lean and hard from life at sea. You didn’t go soft in my line of work. “I’m not yet five and twenty, Mother.” I held up the box and stared at it. “What if I can’t open it?”

“I suppose you’ll have to pass it on to the next generation.”

“There won’t be a next generation.”

She shrugged and waved me away with one hand.

“Give it to Philip.” I held it out to her, but she shrank back from it and her eyes moistened at my brother’s name. What had he been up to now? Likely he was the one who’d spent all her money. I hadn’t seen Philip for seven years, but I doubted he’d reformed in that time. He’d been a sweet babe, but had grown into a spoilt brat, manipulative and selfish, and last I saw he was carrying his boyhood traits into adolescence, turning into an opportunist with a slippery tongue.

“Always to the firstborn. But you’re behind the times, girl. Philip’s dead. Dead these last seven months.” Her voice broke on the last words.

“Dead?” I must have sounded stupid, but an early death was the last thing I’d envisioned for Philip. The grievances I’d held against him for years melted away in an instant. All I could think of was the child who’d followed me around, begging that I give him a horsey ride or tell him a story.

“How?”

“A duel. In London. A matter of honor was the way it was written to me.”

“Oh.” It was such an ineffectual thing to say, but right at that moment I didn’t really know how I felt. Had Philip actually developed a sense of honor as he grew? Was there a better side to my brother that I’d never seen? I hoped so.

“Is that all you can say? You didn’t deserve a brother. You never had any love for him.”

I let that go. It wasn’t true.

“I thought you might have changed.” My mother’s words startled me and I realized my mind had wandered into the past. Stay sharp. This might yet be a trap, some petty revenge for the wrongs she perceived that I heaped on her: loss of wealth, loss of station, now loss of son. Next she’d be blaming me for the loss of my father, though only the sea was to blame for that.

“That’s all I’ve got for you.” She turned away from me. “It’s done. Now, get out.”

“Mother, I—”

“I’m ready for my medicine.”

I knew it would be the last time I’d see her. I wanted to say how sorry I was. Sorry for ruining her life, sorry for Philip’s death. I wanted to take her frail body in my arms and hold her like I could never remember her holding me, but there was nothing between us except bitterness. Even dying, there was no forgiveness.

I turned and walked out, not looking back.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved