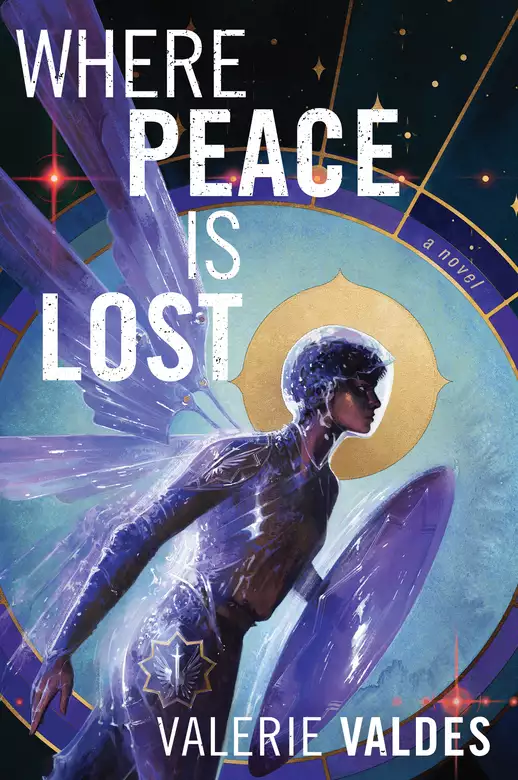

Where Peace Is Lost

- eBook

- Audiobook

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

A brand-new space fantasy novel from master world-builder Valerie Valdes! A refugee with a secret, a dangerous foe, and a road trip that could either save a planet or start a war.

Where peace is lost, may we find it.

Five years ago, Kelana Gardavros lost everything in the war against the Pale empire. Now Kel Garda is just another refugee living on the edge of an isolated star system. No one knows she was once a member of an Order whose military arm was disbanded and scattered across the galaxy. And no one knows that if her enemies found her, they might destroy the entire world to get rid of her.

Where peace is broken, may we mend it.

Kel’s past intrudes in the form of a long-dormant Pale war machine, suddenly reactivated. If the massive automaton isn’t stopped, at best it will carve a swath of devastation that displaces thousands of people. At worst, it will kill every sentient creature on the planet.

Where we go, may peace follow.

When two strangers offer to deactivate the machine for a price, Kel and a young friend agree to serve as their guides. The journey through swamps infested with predators and bandits is bad enough, but can they survive more nefarious dangers along the way? And will Kel’s fear of revealing her secrets doom the very people she’s trying to protect?

Where we fall, may peace rise.

Release date: August 29, 2023

Publisher: HarperCollins

Print pages: 448

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Where Peace Is Lost

Valerie Valdes

Kel hung upside down from the side of the enormous xoffedil she’d been climbing and reconsidered her life choices.

The creature thankfully hadn’t noticed her distress; if it did, it might reach back with its long, tentacled proboscis and try to yank her off. This might tear out a clump of its fur and make it violently angry, sending it charging into the forest with Kel in its furious clutches. Or it might rip Kel’s leg off at whichever joint was weakest, and she’d probably die of shock, pain, or blood loss long before anyone noticed she was missing.

Or it might eat her. Or all those things in no particular order.

None of the options appealed, but admittedly, nor did being stuck with her booted foot going numb while leaves and branches slapped her face and arms with every step the creature took through the trees. Above her—or technically below her—a slash of lavender sky flashed in and out of view, flanked by walls of vegetation as the xoffedil lumbered along its path. Birds hummed or whistled deeper in the green, occasionally taking to the air with a scream, and insects clicked their carapaces and rattled their wings in defiance of the predators lurking in the underbrush, eager for a crunchy snack.

With a grunt of effort, Kel wrenched herself up by bending at the waist, then fumbled for the rope wrapped around her ankle. Her muscles strained as she pulled until she was vertical, climbing further up to ease the tension on the knotted loop. Wrapping a length of the cord around her wrist a few times, she reached down and bent her leg, grabbing the loop and tugging it over her boot’s heel. All this work to scale the creature for a few fistfuls of kexeet—the valuable rainbow moss growing on its shaggy fur.

The xoffedil trumpeted, and Kel jerked in surprise, nearly losing her grip. In the distance, a similar call replied. Oh spirits. The giant hexapod wasn’t out looking for food; it was trying to find a mate.

A series of new potential methods of dying spread out before her like a feast in the village. Xoffedil were extremely vigorous in their reproductive activities. Kel had to get away before the two creatures reached each other.

Abandoning all hope of a profitable harvest, Kel clambered up the xoffedil’s flank as fast as she could. She reached the spot where she’d attached her anchor line to its fur, decoupling the elaborate series of clips that spread her weight around. The more she moved, the more likely the creature would notice her presence and try to rid itself of an unpleasant pest. If she lost her grip on the way down, she could easily fall to her death. If she survived the four-story drop, she might be crushed by a foot the size of an armed transport.

If this were simple, everyone would do it, Kel thought. And the price of kexeet would be much lower.

Slinging the anchor line and clips diagonally across her back, Kel climbed sideways toward the creature’s nearest thigh, its swaying gait making the task more difficult. Knots in the fur served as natural hand- and footholds, but she paused between movements to avoid attracting attention, slowing her down. The xoffedil trumpeted again, the answering call closer now.

Kel sped up, halving the distance to the middle leg. She could do this. Just a little farther. Not for the first time, she wistfully considered how much easier this would be if—

A flash of movement caught her attention: the xoffedil’s whiplike tail, heading

right for her.

Kel dug in like a tick and clung to the creature’s side. The thick tail slid down, its natural curve scraping the fur to the left of her while leaving her untouched. She relaxed her grip and breathed a sigh of relief, the xoffedil’s musky scent filling her nose and mouth.

Then the tail came back up from underneath and flicked her into the air.

For a few stunned moments, Kel flew, higher than she had in years without a flitter. The top of the forest canopy stretched in front of her like a richly woven carpet, shades of green mixed with purples and reds and oranges that might be fruit or flowers.

And then she reached the apex of her flight and fell toward the trees.

Death by falling had always been one Kel expected, even welcomed more than a sudden shot through the head or a blade through the heart. And after everything, perhaps she deserved to die alone. To her surprise, though, she found she wasn’t ready to accept that fate.

Years of training and instinct kicked in, once she overcame her first impossible impulse. Kel relaxed her limbs, tucking her chin close to her chest and covering her face, knees bent. She hit the canopy, vines and twigs catching at the ropes and clips slung across her back even as they whipped her legs. While she might slow her descent by grabbing a branch, she could also break or dislocate an arm, so she resisted the urge.

The density of the vegetation thinned as she plunged into the dim light of the understory. Below her, a sun-dappled assortment of shrubs, ferns, and moss-covered saplings fought for supremacy over the ground. In other circumstances, she might have better control over where she landed, but now she was entirely at the mercy of gravity. Down she went, mentally preparing herself for a hard landing, hoping she’d be able to execute a maneuver she hadn’t practiced in years—

The ropes on her back went taut and yanked her to a halt, burning her skin and pressing sharply against her chest and underarms. She dangled long enough to draw a shuddering breath and assess that she had about two stories left before she hit dirt. Whatever branch had caught her sagged beneath her weight, then snapped, sending her once again plummeting to the forest floor.

The shock to her feet on landing quickly dissipated up her legs as she rolled awkwardly

sideways, finally coming to a stop flat on her back after two full rotations. The branch, still attached by her ropes, missed her by a handbreadth. Above her, only the barest gap in the canopy existed to indicate where she’d entered, and she had no doubt it would be gone within a month. The plants cared little for the passing of humans, and kept their own counsel.

Kel inhaled tentatively, wary of bruised ribs. Her only pains were external, skin and muscle and dull aches in her joints that would no doubt worsen. She was lucky. If she told the villagers the story of what had happened today, when she brought them the kexeet, they’d probably tease her about the poor quality of her bird impression. Or they would say the planet had offered her its protection and she should be honored. And yet, despite her previous desire to continue living, she had trouble feeling good about it.

Where we fall, may peace rise.

Old memories Kel avoided came rushing back, and she lay there staring up at the dark underside of the trees feeling miserable and alone. A bug crawled across her arm, then fluttered away, its translucent wings catching the light like colored glasteel. Eventually, grudgingly, she sat up and untangled herself from her ropes, then stood, then began the long walk to her borrowed flitter, wounds new and old aching in her flesh and bones and soul.

A tenday after her xoffedil mishap, Kel sat cross-legged on the small covered porch in front of her house at the edge of the swamp, mending a tear in a spare shirt, when the insects and birds around her fell silent. She didn’t get many visitors, and they usually called out their approach from a distance, to let her prepare for company. The last time she’d been surprised, the poor man who’d come to warn her about an impending storm had left with a wrenched arm and her most profound apologies. He’d spread the word, more for everyone else’s safety than hers.

Still, one person persisted in attempting to sneak up on her.

“Lunna,” Kel said, calmly continuing her work. “You’ll be sorry if I stick my finger.”

“How do you always know it’s me, Friend Kel?” Lunna asked, emerging from behind a tree. Their coppery hair fell over their shoulder in a single braid interlaced with colored threads, loose wisps framing their narrow, freckled face and bright blue eyes. They wore their usual brown tunic over a long-sleeved shirt, with comfortably loose pants tucked into knee-high boots. Also as usual, they brimmed with barely contained excitement, though it seemed to be overflowing today.

I don’t always know it’s you, Kel thought. Every time she guessed it was Lunna, part of her whispered that it could be someone else, and her presumption would mean her death.

“You have news,” Kel said instead. “Go on, before you burst like an overripe stinkmelon.”

“You could at least pretend to be interested,” Lunna said, flinging themself down on the wooden floor next to Kel.

Kel pretended a lot of things, to her shame, but not this. “Well?”

Lunna grinned back, then leaned forward conspiratorially. “There’s been a sighting. A Pale war machine.”

Now Kel did stab herself with the needle, hissing in surprise and pain. “A war machine?” she asked, sticking her bleeding thumb in her

mouth.

Lunna nodded. “One of the really big ones. Bigger than a xoffedil.”

Flashes of memory assaulted Kel. She sucked her thumb hard.

“Where is it now?” she asked.

“Still in the Parched Fields, I expect.” Lunna stroked a puffy weed that grew in a crack between two boards. “My parents sent me to tell you there’s an all-villages meeting to decide what to do about it. In Esrondaa, tomorrow night.”

Esrondaa was the only true city in southern Loth, where the spaceport was located. A meeting there meant thousands of people from dozens of villages cramming into the open-air amphitheater where such business was conducted. Anyone was allowed to attend, but many would simply give their opinions to some chosen representative to pass on in their place.

Kel didn’t make a habit of involving herself in local politics, even though she’d been living on Loth for almost five trade years. The locals knew their own business better than she did. Still, every time there was a meeting, Lunna or someone else from their village, Niulsa, was sent to invite her. Every voice mattered, they always said. Kel had believed that once, too.

This time, though, she might actually go to this meeting. A Pale war machine was no trade or farming discussion. While Loth wasn’t an official territory of the Prixori Anocracy and hadn’t been among the planets caught up in any recent wars, the Pale had exerted political pressure to be permitted to set up a temporary base in the northern part of the continent. They had promised to withdraw after their war at the time ended, and for the most part they had done so.

Unfortunately, they’d left a few things behind. Always at war somewhere.

“Has someone been notified?” Kel asked.

“What, like the Pale?” Lunna asked.

“Yes,” Kel said. Best to report it and stay well away.

Lunna’s bright expression dimmed. “That’s why we’re having the meeting. It was reported right away, but the Pale say they won’t send anyone.”

“Impossible.” The war machines were dangerous. They couldn’t be left roaming about.

Lunna shrugged. “They said it’s low priority and they’ll take care of it when they can. Something about resource allocation? You could

have lit a cookfire with the flames coming from my ma’s eyes.”

Kel felt pretty heated herself. That settled it. She was definitely attending the meeting. Perhaps the people who contacted the Anocracy hadn’t explained the problem adequately. She needed more information and, if necessary, she had to ensure none of the locals attempted something foolish—like trying to stop the machine themselves.

“I should pack,” Kel muttered, staring down at the half-mended shirt in her hands.

“You’ll go?” Lunna asked, clapping their hands in delight. “Oh, bring me, please? My parents said I could go with whoever went, but Leader Thrim already conveyed her regrets, and her counsel. I think they assume no one else will want to go.”

They likely didn’t want Lunna to go, Kel thought, but didn’t want to oppose the request outright. At twenty-two trade years old, Lunna was entitled to make their own choices; even so, they would always be a baby to the people who’d raised them.

Even Kel sometimes saw the fresh-faced eighteen-year-old they’d been when she first met them, instead of the adult they’d matured into. At their age, Kel was already somber and star systems away from the planet where she was born. Lunna, by contrast, retained a youthful brightness and optimism, still lived at home, and had responsibilities to their family and the village.

Perhaps Kel should discourage them with a carefully placed nudge?

“Don’t you need to finish repairing the village’s fabricator?” Kel asked. “Before your family leaves for the trade fair?”

“We won’t be leaving until the war machine problem is solved anyway,” Lunna said. They tilted their head in thought. “Now that you mention it, I do need to get a new belt and print head. Can’t fix the fabricator without them, and the only supplier is in Esrondaa. It’s a perfect excuse!”

She’d hoped to convince Lunna to stay, not give them a bespoke reason to go. “You’re safer here,” Kel said, knowing how weak it sounded.

“I can choke on a bone anywhere,” Lunna retorted. Their tone became wheedling. “You shouldn’t travel alone, either. You know I love seeing the spaceport, and I know all the villages and paths between here and Esrondaa.”

“So do I.”

“Please,” Lunna begged, their blue eyes wide with longing. “I’ll keep asking until you agree. I’ll . . . I’ll stand outside your window and make fyoo calls all night so you can’t sleep!”

Kel snorted a laugh. “Threats? Not bribes?”

“You won’t take bribes,” Lunna said dismissively. “And anyway, we both know I won’t do it. I might lure a real fyoo here, and then I’ll have to stay home until I get the stench off.”

“True,” Kel said. “And you’ll have to clean the stench out of my home as well.”

Lunna’s laughter rang out, loud enough to send a flock of birds—probably not fyoo—winging into the sky. They leaped to their feet and gave their lips a perfunctory flick of goodbye with two fingers.

“I’ll be here at first light,” they said, nearly skipping down the path through

the trees.

“Talk to your parents,” Kel called after them. “Be sure you’re not leaving them floating in the swamp without a pole.” Until Lunna made good on their grand plan to travel the stars someday, they couldn’t simply flit away without a care.

Kel had worked hard to earn her quiet life here after the war. Part of that meant ensuring she followed village customs as best she could, and didn’t cause anyone trouble. The last thing she needed was to draw attention to herself.

Which she would be doing by traveling to Esrondaa. She would have to be careful there. Keep her hair covered. Let Lunna do the talking. If it seemed like the Speakers were going to make a poor decision, she’d figure out some way to intervene.

With a sigh, Kel returned to her mending. She had planned to try another kexeet harvesting trip soon, and instead she’d be making a journey that could prove far more dangerous. But at least she would have an extra shirt to bring with her.

True to their word, Lunna arrived just as the sun rose, its rays peeking between the high arching roots of the mangrove trees and shimmering across the surface of the water. Kel had gone for her usual run and now waited in the same spot on the floor as if she hadn’t moved all night, except a pack sat next to her, heavy with supplies. While they should reach Esrondaa within a half day, swamp and weather willing, she didn’t want to be underprepared.

“Morning!” Lunna called cheerfully. “Ready to go?”

Kel ran through her mental inventory once more. Sleeping tarp, bedroll, rations, shirts, pants, underclothes, socks, sandals. The daily pills that made local food edible to people like her who hadn’t been modified. Her raincloak was crammed through a side loop so she wouldn’t have to open her pack to get it when it rained. She’d strapped a machete to her thigh, more for vegetation than defense, and her long walking stick was propped against the wall next to her front door.

She’d also spent half the night arguing with herself over whether to bring other items, ones she had hidden years earlier under the foundation of her one-room house. If she had them, she would be tempted to use them, she told herself, and that would reveal her presence to anyone with the knowledge to recognize what she was, so it was better to leave them behind. Better not to take the chance of being found by her enemies. Better to leave the past buried, quite literally.

But if she didn’t have them and needed them against the war machine, what then? Would not having them be more dangerous? Could innocent people be needlessly harmed when her intervention might have saved them? She would have to suffer that burden on her conscience with all the rest, and that load was already heavier than the pack she would carry to Esrondaa.

Was it weakness or strength that drove her to preserve her anonymity? Was it fear, or the last frayed strands of her honor?

In the end, Kel wriggled into the narrow space underneath her house, ignoring the bugs and mold and muck that smelled faintly of bad eggs, and retrieved the container that held the last vestiges of her old life. Her sword stayed where it was; few people on this planet carried such a weapon, so it would immediately call attention to her. She also left her uniform, its fabric impermeable and comfortable in virtually any climate, but eminently recognizable. She did take her ellunium bracers, which she could easily hide under her shirtsleeves; anyone who happened to glimpse them might mistake them for decorative cuffs or some similar adornment.

It was the best balance she could think of between secrecy and preparedness. And if the worst came to pass, she had one other skill to rely on.

Lunna’s easy laugh interrupted her musing. “I thought it was a simple question,” they said. “I should have known you would give it a great deal of thought.”

“It comes of being older,” Kel replied. “I know what it’s like to run off with my boots half laced.”

Lunna laughed again. “You’re not old, Kel,” they said. “You’re just broody as a hen. Come on, I want to be there before I’m the one who’s old.”

Kel picked up her pack and slung it across her back, then took up her staff and trailed after Lunna. When she reached the tree line, she paused and looked at her small house, at the carefully laid wooden beams and fitted slats, the roof covered with broad palm leaves and sealed with tar, the wide porch where she’d sat and watched the rain come down in sheets year after year, dreaming of other places and seasons.

She tried to tell herself this was just another journey, no different from traveling to the xoffedil territories or any of the villages beyond Niulsa. But none of those trips had involved the Pale or their war machines. None had come so close to trailing their cold fingers along scars that still itched and burned and startled Kel with a pain like fresh wounds.

The wind picked up, sending clouds overhead scuttling across the brightening sky and bringing with it the smell of coming storms. No sense delaying the inevitable, Kel thought. She turned away and left.

Despite dark clouds dumping buckets of warm rain on them, turning the roads into rivers of mud, Kel and Lunna arrived in Esrondaa just after midday. Rows of colorful outer buildings made of wood and mud bricks and recycled metal sheets gave way to mosaic-covered concrete and tinted glasteel, the structures growing taller and closer together in clusters around communal gardens or buildings or intersections. Passenger transports cautiously nudged their way through the groups of people walking or riding from place to place, and unicabs darted around all of them with a recklessness born of skill and experience. Volunteers carried long poles with bags of fruit picked farther afield, or set up fireboxes where the day’s catch sizzled over open flames, while vendors pushed umbrella-covered carts full of handmade or fabricator-printed goods around the perimeters of the parks.

At the center of the town, the largest of the gardens grew in carefully managed quadrants, nearly as big as all of Niulsa. Some of the trees, vines, and ground plots were currently laden with almost ripe fruit, berries, and vegetables, while others waited for their natural turn to bud and bloom. Still others had already been harvested by robots or people, the food arranged for easy access in nearby bowls and boxes, or sent to a factory for processing and distribution. Insects drifted between the flowers whose sweet scents perfumed the air, humming serenely, oblivious to the emotions of the humans around them.

Along with dozens of other people, Kel and Lunna ate a late meal sitting on a broad wooden bench near one of the public water dispensaries, the sun drying their damp clothes with the help of a warm breeze. Kel even splurged and bought them each a crispy flat bread from a street vendor, the buttery top sprinkled with sugar and chopped nuts.

The meeting wouldn’t be held until the sun went down, so they had plenty of time to rest and relax—except Lunna wouldn’t allow it. With an energy that belied their journey, they dragged Kel first from one shop to the next, delighted at the variety of items on display for barter or the infrequently used local currency called scales. They bought the necessary parts for the fabricator, bargaining earnestly and cheerfully. Then they went to the spaceport, a tall spire stretching higher than any other buildings or trees, to see the landing platforms and the interstellar communications hub and anything else that was publicly accessible. They tried to beg a ride on a flitter from one of the attendants, who gently rebuffed them, which is how Kel learned that flights across the planet had been grounded due to the war machine. An overreaction, maybe, since the machine’s scanning radius was about twenty standard marks, but if some curious soul decided to fly nearby to catch a glimpse, it could interpret them as an enemy unit and act accordingly.

Better safe than scorched, Kel thought. At least road and water travel were still possible, even if they took longer.

Their proximity to the port also meant she saw an unfamiliar starship land. Loth didn’t get much traffic, far as it was from galactic trade routes, and the Pale had apparently decided it was too poor in coveted resources for them to conquer and strip-mine. Only the kexeet that grew on the xoffedils held any interest for them, since that was unique, and locals used it to make a particularly fine, beautiful cloth. Kel had heard complaints that inferior artificial imitations were starting to flood the market, but it hadn’t driven down prices yet.

The ship looked like an interstellar transport, big enough to have a warp drive but small enough to land instead of staying in orbit and sending down a tender. The shape was more squat than sleek, curved wings tucking themselves against an oblong body.

It was painted a utilitarian gray speckled with small blue and gold dots that might be shapes, if Kel were able to get close enough to examine them. She was more familiar with military craft than civilian ones, but she thought it might be Chonian, which meant the captain could be from a Pale-occupied planet or a border world. Likely not one of the Pale themselves, though; the Prixori Anocracy had their own shipyards and preferred styles, which tended toward unnecessary extravagance and the bone-white hulls that gave the empire their more colloquial nickname.

Odd timing for them to arrive now. And surprising they were allowed to land at all, given the flight bans.

Kel talked Lunna into having their evening meal just before the meeting began, then the pair joined the crowds heading toward the amphitheater. The large structure was as round as a bowl, rising three stories up and one down into the ground, with ramps leading to tier after tier of seating or spaces for wheeled or hovering chairs. Instead of a ceiling, an energy curtain kept the rain out, but the clear, balmy night made it unnecessary. Floral and spicy and green scents from the nearby gardens drifted in on the breeze, mingling with sweat and perfumed oils and the sharp, minty salves that drove away the most obnoxious insects. The dim glow of small lights affixed to the floors cast the assembled faces into shadow, so the processions entering the building appeared strange and mysterious—marching masses of disembodied legs, Kel thought with amusement. But as soon as they cleared the entry tunnels, the setting sun chased away the darkness, and two thousand people, give or take, took their seats to hear about the danger the Pale had inadvertently brought to their thresholds.

Lunna paused in their perusal of the assembly, leaning closer to Kel. “Are you going to say something?” they asked.

Kel shook her head, gripping her staff more tightly. Lunna had discussed the concerns their parents wanted raised along the way, and Kel thought they were reasonable—mostly worries about evacuation criteria, mutual aid needs, and destruction of habitats. They were likely to be mentioned by someone else before Lunna got a turn to speak. Kel had always been more inclined to listening than talking anyway, so she leaned against the wall behind her and settled in to do just that.

A few stragglers were still making their way inside when a platform at the center of the amphitheater was illuminated by a large, bright spotlight. An older woman limped across the stage, leaning on a cane, wearing a simple belted dress in a red fabric that complemented her coppery skin. Her white braided hair was threaded with green and purple and gold, among other colors, arranged to signify her personal pronouns, birth village, marital status, and position in the local government: Speaker for Esrondaa, which meant she had likely prepared

a statement on behalf of the city’s council and anyone who had given her their thoughts in advance.

“Be welcome, friends,” she said, her husky voice amplified by some hidden receiver. “Our water is your water.”

“Our sky is your sky,” the assembly replied in unison, raising their cupped hands.

“I am Speaker Yiulea,” the woman continued, “and I am sorry to meet you all in a time of fear and uncertainty. As you were informed, a Prixori Anocracy war machine was discovered approximately two days ago, by an ecologist retrieving soil data in the Parched Fields. Specifically, this is the SIARV-417 Mark 3, commonly known as a demolisher. It is approximately five trunks tall and three times that length, and weighs over ten thousand stones.”

Gasps and mutterings went up among the crowd, from people who perhaps hadn’t been fully aware of the sheer size of a demolisher. The biggest creature they routinely interacted with was the xoffedil, and those were mostly viewed from afar unless they were being climbed by kexeet harvesters.

And that’s just one of the Pale’s land units, Kel thought bitterly. They have battlecruisers as large as Esrondaa.

Speaker Yiulea lifted a hand and the chatter lessened. “The demolisher will reach the Gounaj Gulch in seven days, and at its current pace, if it is not stopped, it will reach the Verdwell Basin in ten days.”

The xoffedil breeding grounds were in the Verdwell Basin. The scattered whispers now turned to exclamations of dismay and outrage. Some people sprang to their feet and gestured emphatically, while others commented to their neighbors or absorbed the information in stony silence.

“Ten days!” Lunna said, shaking their head. “What will it do when it gets there?”

Nothing good, Kel thought.

As if she’d heard Lunna’s question, Speaker Yiulea said, “Our understanding of Prixori defensive programming suggests the demolisher will not attack the xoffedil unless provoked, but what it considers to be provocation is unclear. Even if it did not begin an assault, its mere presence will almost certainly destroy the breeding grounds, given the damage it has already done to the land from its passage.”

“Stop it, then!” someone yelled, loud enough to be heard over the crowd.

“If you have a comment,” Speaker Yiulea said calmly, “please save it for when we open the discussion after I conclude my remarks.” She waited for the noise to settle from a boil to a simmer, leaning on her cane with a poise that made Kel smile wistfully at the memory of someone like her.

“The Prixori have been contacted,” Speaker Yiulea said finally. “Their representatives were apologetic—and yes, we spoke to more than one—but they assured us they could not spare anyone to deactivate

the machine immediately. We have been added to their support queue and will be helped as soon as possible.”

“What does that mean?” came another shout.

Speaker Yiulea ignored them. “The most important thing we can communicate to you now is: do not go anywhere near the demolisher. We have already sent out warnings, but we want to emphasize this again. If the machine believes itself to be under attack, it will retaliate overwhelmingly.”

Once a demolisher went into attack mode, it would remain in that mode until every designated enemy on sensors was killed. It would pursue anyone marked as hostile, ...

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...