I’m not sure what else to say about Rose. If you know me at all, then I doubt that’s surprising. I suppose I could tell you more about how we got to know each other. How she took me to the inn that afternoon, where we sat outside in the shade of the redwood trees, and I told her how much I liked her shoes—they were made of this bright camel-brown leather and were shinier than anything I’d ever seen. Rose smiled when I said this, pleasing me that I’d pleased her. Plus, she was pretty like her shoes—shiny and rare and right in front of me; I was entranced, watching feverishly as her lips moved and her legs crossed while she rambled on about life with her French-Peruvian parents and dour-faced twin brother, who, she hinted, in a provocative voice, had serious issues of some mysterious nature.

I could tell you how she pined daily for the city she’d left behind. The people. The music. The food. The culture. Being able to see a first-run movie every now and then. Owning the inn might’ve been her parents’ dream, but Rose thought for sure she was going to leave this place someday. The town of Teyber was just a way station on her march to Somewhere, and I supposed I was, too. Rose had plans for college. Graduate school. To be special. Be the best. That’s one way we were different. From my vantage point, there was no hope for escape; I’d reached my zenith, a dim, low-slung, fatherless arc, and had long stopped believing in more.

I could also tell you how, in the two years we dated, Rose was my first everything. First kiss, first touch, first girl to see me naked and lustful without bursting into laughter (although she was the first to do that, too). We did more eventually. We did everything. Whatever she wanted. Rose dictated the rhyme and rhythm of our sexual awakening, and I loved that. I never had to make up my mind when I was with her.

By the way, I have no problem admitting I was nervous as hell the first time we actually did it—both of us offering up our so-called innocence during an awkward Thanksgiving Day fumbling that happened on the floor of the locked linen closet at the inn. For an awful moment, right before, as I hovered above her on the very edge of a promise, I feared I wouldn’t be able to—my ambivalence runs deep—but Rose stayed calm. In her steady, guiding voice, she told me what to do and just how to do it. I was eager to listen. I was eager to be what she needed.

I don’t know. There’s more to say, of course, much more. Two years is a long time in a short life, especially when you’re in high school. But that’s not the Rose anybody wants to read about, is it? Tragedy is infinitely more interesting than bliss. That’s the allure of self-destruction. Or so I’ve found.

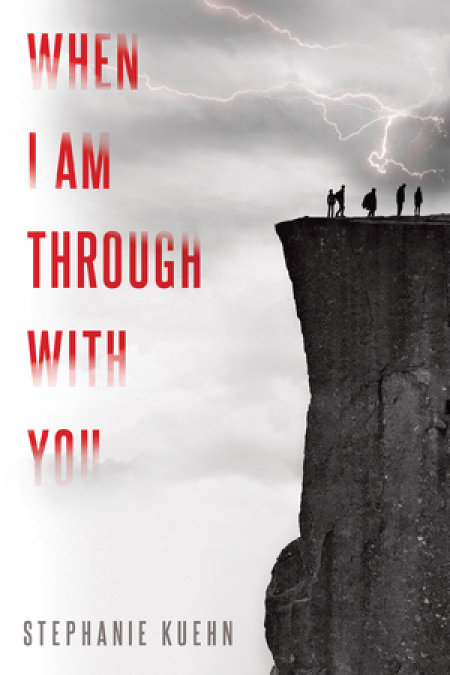

But I’ll end with this: I miss Rose. I’m even glad I met her, despite what happened on that mountain. There were bad parts, yes; if I had my own days of darkness and suffering and pain-imposed sensory deprivation on account of my headaches, then in between her moments of verve and brashness, Rose had her own kind of darkness—bleak and savage, like a circling wildcat waiting to eat her up. What she needed during those times was for me to keep her alive, and for two years, that’s exactly what I did. And whether I did it by making her laugh or making her come or shielding her from her fears of tomorrow by giving her all my todays, I did it because she told me to and because I loved her. Truly.

So why’d I kill her?

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved