- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

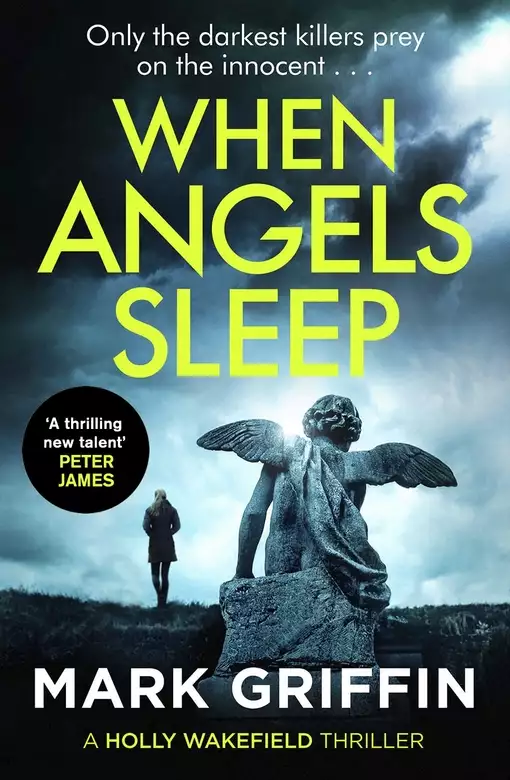

Synopsis

On a cold winter's morning, the body of a young boy is discovered in Epping Forest.

The body is pristine and peaceful, his head resting gently on a pillow, an angel pendant clenched in his small fist. It is a murder as carefully planned as it is brutal, and there's one person DI Bishop needs back on his team to help solve such a calculated crime.

Holly Wakefield, clinical psychologist for the Met Police, is better than anyone Bishop knows at getting inside the brains of psychopaths. But with the body count rising, it's going to take all Holly's strength to dive into the murky mind of someone who preys on young boys. And all Bishop's resolve to stop the serial killer before any more angels are put to their rest . . .

The second gripping thriller in the Holly Wakefield series, from the acclaimed author of When Darkness Calls. A dark and twisted serial killer thriller perfect for fans of Val McDermid, Mark Billingham, Stuart MacBride and TV crime series Luther.

Release date: November 28, 2019

Publisher: Little, Brown Book Group

Print pages: 397

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

When Angels Sleep

Mark Griffin

He had a lovely voice. Mellifluous, his singing teacher had once told him – a nightingale set free in the dark. When he had sung at school and the local church, he had always closed his eyes and fantasised.

My life is not beautiful, he used to think. It is not magical. But I can feel the love. Coming closer. Closer every day.

He had been asked to join the choir when he was thirteen – high praise indeed for a school of two hundred pupils, and when he had been asked to sing a solo in St Mary’s church in Chigwell that Christmas Eve, and his mother had watched from the wooden pews amongst the other mums and dads, he had thought for the briefest of moments that he actually was in heaven. There had been no applause or welcome hug after, but the fleeting smile had been enough. That was twenty-three years ago. How he had grown since then.

He turned into his driveway, parked the car and got out. It was February and cold. Blobs of cloudy snow littered the grass and the ground was slippery with wet. A quick wave at the light-sensor so he could see the lock, and then he turned the keys and pushed open the front door. The house was dark. It always was. Black wood panelling, sombre brown floors. A Gothic hallstand with an elephant’s foot base. He switched on the hall light. Tiffany stained glass that splashed gummi-bear colours all over the walls. Placed his suitcase on the hallstand and called up the steep stairs.

‘Hi, Mum!’

‘Is that you?’

‘Yes!’

‘You’re early.’

‘I’m going out tonight.’

‘What?’

‘I’m going out. Remember?’

He went into the kitchen, put the kettle on the stove and made himself a cup of tea. Five minutes later he put two sausages in the frying pan and watched them sizzle like fat fingers until they were brown all over. He boiled some peas, cut the sausages into edible-sized chunks, buttered two slices of wholemeal bread and put everything on a tray with some cutlery.

The stairs were surprisingly noiseless for a house this old, a Victorian throwback that was neither loved nor lost. He hoovered twice a week, but the dust always seemed to settle as if dropped by a sieve, and he couldn’t help running his finger over the banister when he got to the top. He took a left on the landing, past two bedrooms, the bathroom, and entered his mother’s room. The curtains had already been drawn, and the only light was from a lamp on the bedside table. The sixty-eight-year old woman was perched like a giant crow in the bed. Propped up by pillows, her emaciated arms draped across the duvet and her black lace nightdress was buttoned to the neck. Her head hung forward and was tilted slightly to one side. Her eyes seemed to follow him but her head never moved.

‘Where are you going then?’

‘I’ve told you, Mum. It’s a works do.’

‘Works do?’

He placed the tray of food gently on her lap.

‘Come on, eat up before it gets cold.’

His mother stared at the food, then picked up the knife and fork and started to eat. She chewed a piece of sausage loudly. ‘What time will you be home? Last time you left me I thought you were dead.’

‘I’ll probably be late. We’re all going to the Cosy Club, it’s—’

‘You needn’t go into detail. I hope I didn’t raise one of those boys who always tell you exactly what they’re doing when you ask them?’

‘No, Mum. Of course not.’

She had spilled peas onto the duvet and they rolled around like baby marbles. The man started to scoop them up but was interrupted by a quick rap on his knuckles with a fork.

‘I haven’t finished with them. Stop hovering! And where’s my tea?’

‘I forgot,’ he said, and quickly left the room.

Downstairs he re-brewed the kettle and made his mother a cup of tea. He put two Jammie Dodgers on a plate and headed up the stairs again. She was fiddling with the bedside lamp when he entered. The light was flickering like an SOS.

‘What are you doing, Mum?’

‘Trying to fix the . . . It’s always doing this.’

‘It’s fine. Just . . . hold on.’ He put the tea and biscuits on her lap. Went to the other side of the room and pushed her wheelchair to one side. Knelt down by the washbasin and opened a small door that was hidden behind. He went through to the next room, and when he returned a minute later the light had stopped flickering. He closed the door and pushed the wheelchair into place. ‘There you go. Nice and quiet. I need to get ready now.’

He had already showered and shaved that morning and opened the bag he had left on his bed. Looked at the clothes inside and added a pair of flat shoes and an iPhone. He shot himself a smile in the mirror but it ended abruptly when he felt suddenly sad. Stop it, he said, and he grabbed the St Jude medal around his neck. Stop it. Stop it. His eyes went to the ceiling where the painted angel mural was watching and he gave himself a minute.

By the time he went back into his mother’s room she was asleep, her gentle snoring like soft waves on a beach. The man wasn’t sure whether he should wake her, but—

‘I’m off now, Mum.’

‘Hmm . . .’ his mother stirred.

He leaned in closer and gave her a kiss on the cheek. Smelled her breath, her old hair. She squinted at him with rheumy eyes and wiped a bit of sausage fat off her chin.

‘Where’s Stephen?’ she whispered.

‘Don’t wait up for me,’ he said, his breath catching in his throat.

He took his mother’s tray and went downstairs. Washed everything up, put it all away, and placed a box of Weetabix on the kitchen table ready for breakfast.

‘Bye, Mum!’ he shouted up the stairs as he made his way into the hall, but he didn’t leave yet. He opened the front door then slammed it shut and stood in absolute silence. Listening for a soft footstep or a scrape of furniture. Barely daring to breathe. Five minutes. Ten. Nothing. Then he caught a glimpse of himself in the hall mirror and the sadness returned like a black wave. His head fell forward onto his chest and he cried for a full minute. The sort of crying where he had no idea if he would ever stop and his head hurt and his heart pounded and his face was a mess but he didn’t care. And he couldn’t see because everything was blurry and nothing looked real and he couldn’t feel pain because pain didn’t exist any more – there was only the never-ending slog of sadness.

‘What am I like . . .’ he sniffed. And after several minutes he rallied bravely, because deep down he knew exactly what he was like.

He was a lonely man with so much love to give, but nowhere to put it.

‘Are you drunk?’

It was a good question.

Someone had banged a nail into Holly Wakefield’s head about two hours ago and no matter how much she tried to find it she just kept grabbing tufts of hair. Dirty hair. Smelly hair. Cigarettes and rhubarb gin.

‘I think I might be,’ she managed.

She pulled herself upright and her eyes flipped open, a newborn shrew seeing the sun. And then there was something she hadn’t felt in a long time: the stomach lurch. The room spun and she wondered if she was going to be sick.

‘Are you going to be sick?’

Another really good question. Detective Inspector Bishop was on fire today.

‘Possibly.’

Hold it in. Hold it in. For God’s sake, hold it in.

Who had suggested shots at four thirty in the morning? It had started with gin and tonics at eight last night. A reunion with the girls from Blessed Home, her foster home from when she had been a young girl. Valerie, Sophie Savage, Michelle, Joanne, Rhonda, Zoe. Sixty-two flavours of gin? Who even knew that was possible.

Then they had all decided on something to eat.

Soho – where else?

Balans on Old Compton Street – it had to be.

And after they had been kicked out at 2.00 a.m. they had gone to a members-only club on Shaftesbury Avenue. The Connaught, or something. No – the Century Club, that was it, and they had stayed there until they went on lockdown. Valerie was a member and got them in and then the party had really begun. Sophie had fancied one of the waiters and he had told them one of the funniest jokes about a deer, a skunk and a cuckoo. How did it go? A cuckoo, a skunk and a deer went out for dinner at a restaurant one night and when it came time to pay, the deer didn’t have a buck, the skunk didn’t have a scent – and the cuckoo? No, that’s not right.

‘The cuckoo . . .’

‘What?’ said Bishop.

‘Shush. It was a joke from last night. Trying to remember. It was funny.’

Was it a cuckoo? Maybe it was a blackbird or a partridge? It would come to her. If it didn’t she could always ask one of the girls. Ah – the girls. Her girls. All grown up now. All beautiful and smart and strong and lovely. And hard as nails when they needed to be. Good company. Nostalgic until the last round. By four o’clock it had been free drinks, cigars on the terrace and then the singing had—

She was being guided. Gentle hands. One on her shoulder. One on her lower back.

‘Where are we going?’

‘Toilet.’

‘I think I’m okay.’

Stomach lurch number two and then that metallic taste in her throat and she could feel her jaw beginning to lock open as her body was about to—

‘Don’t watch me, please don’t watch me,’ she whispered.

The hands lowered her to the floor and she could feel the fluffy bathroom mat under her knees. Her fingers automatically gripped the rim of the bowl and then it all came up.

He held her hair as she vomited.

And kept vomiting.

‘Good shot,’ he said. And she had no idea if he was being sarcastic.

I wonder if he still fancies me?

And when she finished she found her laugh, because she had remembered the punchline to the joke. It wasn’t a cuckoo! It was a duck! The deer didn’t have a buck, the skunk didn’t have a scent and the duck didn’t have the bill.

‘That’s brilliant,’ she said as she wiped her mouth with her hand, and all of a sudden everything made sense.

‘Better?’

They were sitting in Brickwood Coffee & Bread, an artisan breakfast café in Balham, south-west London. Exposed bricks and wooden planks on the walls and a never-ending supply of healthy food and slow roast coffee. Holly had passed on the food but had taken a kale smoothie. It had tasted like lawnmower leftovers but she had held it down. Good stomach. Love you. Now she was nursing a black coffee.

‘Do I smell of sick?’ she said.

‘Coffee and lack of sleep. That’s what I’m getting from over here.’

‘I’m a classy chick. What can I say?’ She smiled and was suddenly conscious that she hadn’t even brushed her teeth. Their waitress brought out Bishop’s full English breakfast. Holly flinched as if it were part of a horror movie.

‘Is that black pudding?’

‘Yeah, you want some?’

‘I’d rather eat my own feet.’

‘What happened to the “hot chocolate and possibly a quiet movie if our mood takes us” evening with the girls?’

‘We started with good intentions but then it quickly descended into chaos. It was good food. Good drink. I like my girls.’

‘I know you do,’ he smiled. ‘Did you forget about our breakfast?’

‘No.’

Yes.

She had vaguely remembered at six thirty this morning when she had collapsed through the front door and belly-dragged herself into the bedroom.

‘I’ve got something for you,’ he said.

‘Another coffee?’

‘If you want.’ He ordered one then handed over a thin paper folder with no labels or words on the front cover. She started to open it but he closed it gently in her hands.

‘Not over breakfast,’ he said. ‘It’s the final report from the Sickert case.’

There was a mood breaker if ever there was one. Wilfred and Richard Sickert.

Doctor. Bastard. Patient. Bastard.

It had been nearly four months since she had first got the call from DI William Bishop of the Met Serious Crime squad and been asked to walk into a living room containing the freshly murdered and mutilated bodies of Jonathan and Evelyn Wright. He had been a doctor, she his loving wife. Forty years with each other wiped out by a flathead hammer and a wicked blade.

Angela Swan, the coroner, had concluded at the autopsy that the injuries to Evelyn were consistent with a previous murder; that of a British Airways flight attendant named Rebecca Bradshaw. Rebecca had been killed three weeks previously, left sitting propped up against her bed like a life-sized plastic doll. Wrists slashed, head resting against her chest as if she were asleep. Three murders. Similar MO and suddenly Holly had had a serial killer on her hands.

Before that her life had been quite simple really. Well . . . both her parents had been murdered by a serial killer and she had been brought up in a foster home . . . but she still considered herself one of the lucky ones. She had stayed in school, worked hard and gone on to major in criminology. Having had first-hand experience of death, she always wanted to know why. Why do you kill, Mr Sociopath? What makes your brain go tick-tick instead of tick-tock? Now she taught behavioural science to students at King’s College in London and the rest of her week was spent at the Wetherington Hospital on Cromwell Road in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, taking care of mentally challenged patients who had the propensity to kill.

Alongside DI Bishop she had helped track down two of the most brutal and clever killers England had ever seen. Two brothers: Wilfred and Richard Sickert. Born of the same womb, living by the same code. It had taken her to a crofter’s cottage by the sea near Hastings – how romantic – and ended with Richard breaking his neck and her stabbing Wilfred in the heart with the broken thigh bone from one of his previous victims. All in all – an eventful two weeks.

The CPS had briefly considered prosecuting her over the deaths of Wilfred and Richard, but the Commissioner and Chief Constable Franks had stepped in and all charges had been dropped. It was the first time in a long time that Holly had felt as though she had help from other people. That she wasn’t alone. That she had a family. She looked at Bishop, toying with the file. She wanted so much to read it, but then put it to one side.

‘I don’t ever want to know where they’re buried,’ she said.

‘I didn’t think you would.’

Her next coffee arrived and she downed it in one.

‘I’m living life, William,’ she said. ‘Not staying in the confines of my flat any more. It’s quite nice out there. With people.’

‘People are nice. Most of them. When’s your next doctor’s appointment?’ he asked.

‘A couple of hours.’

‘You want me to pick you up? Drive you?’

‘Yes please. I might get lost,’ she smiled and then his phone went. Holly watched him as he talked. He looked younger than his forty-three years. Maybe he’d had a haircut or maybe he was just sitting in good light. He listened for a while longer then frowned and hung up. Shot a look at Holly then returned to his breakfast. Indecision – fleeting – but it was there.

‘I have to go.’ He waved a hand to get the bill. ‘I’m sorry, Holly.’

‘What is it?’

‘It’s a body. Another case.’

‘Can I come? I should come. Hold on, let me get ready—’

‘No, stay. Go to your doctor’s appointment. Make sure everything is fine.’

‘Everything is fine, Bishop. I want to help.’

‘I’m sure you do, but not yet.’

‘At least tell me what it is—’

‘I’ll call you later.’

He left enough money on the table and walked away. The waitress returned before the front door had even closed.

‘More coffee?’

Holly managed a smile but thought it might have looked a bit wonky.

‘Keep it coming.’

Her brother Lee was reading a book when she entered his cell.

He folded over the corner of the page with precision, closed it and placed it face down on the table. Holly sat down opposite. Neutral body-language. Neutral face.

‘How are you today, Lee?’

‘I’m dandy. How are you? How’s the broken leg and mashed head?’

‘Still aches.’

‘Yeah, your face is killing me.’ He attempted a smile but quickly wiped it away. ‘Sorry. I get bored with the conversations here. The therapists. You’re the only one who gets my humour. Who I can have fun with.’

‘When was your last session with Mary?’

‘Mary, Mary, quite contrary, how does her garden grow?’ He pretended to take a hit on a joint. ‘Wretchedly, I would imagine. I saw her two days ago.’

‘What did you talk about this time?’

‘Gardenias and roses, fairies and hidden treehouses.’

‘Seriously?’

‘No. We talk about all sorts of things. She’s put me on a new type of medication. I’m mixing my pills. She thinks it will help but they’re making me tired. Irritable.’

‘What has she put you on?’

‘Fucking Clozapine.’

‘I didn’t know. I’m sorry.’

‘It’s not your fault, Sis.’

‘Any other side effects?’

‘Cramps. Nothing outrageous. Not like I’m giving birth or anything.’

‘What’s the book?’ she asked.

He turned it over and glanced at the cover.

‘A Beginner’s Guide to the Migration Pattern of the Common British Snail.’

‘How is it?’

‘Slow. A riveting tale of digestion and excretion.’ A beat. ‘I can smell it on you, by the way.’

‘What?’ She sniffed her jacket, her hair. ‘The alcohol? No, you can’t. I had a shower.’

‘Good night out?’

‘Yes.’

‘I had a good night last night as well. I had a Pot Noodle and a wank in my cell.’

‘It’s not a cell, it’s a room.’

‘Oh, of course: Hotel Wetherington, I forgot. In which case who do I lodge a complaint with because my waterbed has a puncture and my massage chair keeps breaking down. Oh, and everything smells like mashed potatoes and piss. What would you call this place then?’

‘A secure psychiatric facility.’

‘Not really selling it to me, Sis. How about a very desirable one-bedroom flat situated in a popular London location, well within walking distance of the communal canteen. The accommodation boasts a single bed, a table and two chairs, a modern fitted music stereo system and benefits from anti-riot plastic windows with stunning views of the surrounding brick walls.’

‘Very funny.’

‘It includes dodgy electrics, off-road parking for visitors and a small but pleasant garden to the rear that is available for one hour every day, normally just when it’s getting dark.’

‘Have you finished?’

‘Although one of the neighbours does smell a bit funny and sounds like he’s fucking a cat whenever he’s in the toilets, the property is offered with no onward chain. And the doctors are on call twenty-four hours a day for your convenience.’

‘Have you finished now?’

‘Yes.’

They sat in silence for a while and she studied him in the low light and felt the familiar flush of guilt. Two years her elder, Lee had actually witnessed their parents being murdered by the serial killer the press dubbed as The Animal, while Holly had come in minutes later and only seen the awful aftermath. Before that day, she had only really started to notice Lee when she was about six years old. He was a noise that annoyed her and kept her up at night, sibling rivalry at an early age that had dissolved when their parents had been taken away. They had clung to each other like limpets for weeks after the murders and as she got older he had kept her company. Held her when she felt down. Kissed her on the cheek when there was no one else and always promised that everything would turn out all right. She wondered if in a way it had.

At thirty-eight Lee’s face was sallow and gaunt. Last year the board had talked about his possible parole, and Holly had been asked to come in and interview him about the murder of his male lover – in an effort to garner information that the other therapists seemed unable to extract. She had been successful but parole had been denied and Lee had been in a slump ever since. He probably would be at Wetherington Hospital for the rest of his life, but nevertheless when the candle had been blown out she knew he couldn’t help but feel the darkness around him.

‘You look as though you’ve lost weight,’ she said.

‘I don’t think so.’

‘I want you to eat up all your food. Even if the eggs are overcooked. Eat it all, okay?’

He nodded absently. Eyes straying away.

‘I left my life behind when I was brought inside here.’

‘Of course you did.’

‘No. I mean literally. In a plastic bag at the reception. I keep thinking about that plastic bag.’

‘Why?’

‘Wondering if it’s still there. In some dark cupboard, collecting dust. Collecting . . . what else would it collect?’

‘Nothing probably. But it will be there.’

‘Waiting for me?’

‘Waiting.’

‘That was my life before I was arrested. What was inside. Not much really. Three pounds and fourteen pence. Half a pack of polos. My flat keys, car keys and another key that I found on Latimer Road in east London that I have no idea who it belongs to or which door it will ever open. I think that’s sad.’

‘Why?’

‘Because somebody is missing their key.’

‘I’m sure they had a new one cut.’

‘But it will never be the same, will it?’ he sighed. ‘A receipt from M&S – I ate a chicken salad the afternoon I was arrested, and I still had the plastic fork in my pocket. God knows why. It was wrapped in a paper napkin, I think. The physical things that we hold on to. Like emotions, aren’t they? We find it hard to let anything go. Three sticks of cinnamon-flavoured chewing gum. A Starbucks loyalty card. A Waterstones loyalty card. A Boots loyalty card. I’m very loyal, aren’t I? That’s my life in a plastic bag. Lying in a dark drawer somewhere waiting for me to reclaim it. But I know I never will. Does chewing gum ever go off?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘Probably got the shelf life of a nuclear isotope. All the crap they put in it. Killing us softly, but we’re so happy in our own oblivion.’

He sat in his chair, hands interlaced comfortably across his stomach.

‘I want to go back to reading my shitty book, please. But I appreciate the visit.’

She kissed her fingers and gently pressed them onto his hand. Got up and put her jacket on.

‘How’s the detective?’

She contemplated, shook her head.

‘We’re taking it slow.’

‘Is it time that I met him, do you think? Introduce him to the rest of the family?’

‘No.’

He picked up the book and found his place.

‘He knows about me?’

‘Not that you’re my brother.’

‘Interesting. Would he approve? Of course not. Does he know everything about you?’

‘No.’

‘Secrets are never good in a relationship, Holly. Best to bare your soul and be done with it.’

‘Says the man in a padded cell.’

‘Says the woman who’s lost her way.’

The cold, mechanical whir of an MRI scanner.

Holly lay inside. Pale skinned, her lips slightly parted, eyes closed as if she were asleep. Her light brown hair had been scraped from her forehead so hard it made her face look gaunt. Wearing a white hospital gown she could have been on an autopsy table in a mortuary.

‘Holly?’

Her eyes twitched then opened. Deep and dark brown. But the whites were cracked and scarred with tiny red veins. Lost sleep, lost time, lost everything. She stared up at the metal tube as it whirred and hummed around her like a human-sized convection oven.

‘How are you feeling?’

‘Like a kebab.’ Her throat was dry. Scratchy.

‘Another couple of minutes.’

Great, she thought. Another one hundred and twenty seconds to think about Bishop, where he was and why she wasn’t with him. They’d had a few special evenings over December. Hot chocolate, her evening fix after 6.00 p.m., tucked up on the sofa, conversation and then something on the television. No crime drama though when they switched on Netflix – it was their house rule – and she wondered if they would actually find time for each other this year. Maybe go somewhere for a proper meal. See a show. Cocktails? But not today. Today she was lying in a tube of metal waiting for the specialist to evaluate her recovery after the damage Wilfred had inflicted on her in their final fight.

Living the dream, Holly. Maybe she should buy a cat? Maybe she should get a cat and go and live in the Cotswolds or something. Nice and bland. A distinct lack of sadists and killers hiding in the Cotswolds, she thought. Or maybe not. Maybe they just haven’t been caught yet.

‘Okay. Holly. We’re done,’ the voice of God said. ‘You can move now.’

She didn’t want to move. Today she wanted to stay completely still and do nothing. Today all she wanted was to sleep.

She was sitting in an armchair in the specialist’s office.

His name was Dr Breaker. He was in his forties and lean and wore wire-rimmed glasses and had told her when they first met that he liked to paraglide at the weekends. She didn’t give a shit.

‘Considering the brutality of the assault you suffered, you seem to have recovered remarkably well,’ he said. ‘The right eye socket is still in a very slight state of dysfunction. Any loss of sight? Zigzag lines at the edge of your vision?’

‘No.’

He slipped the colourful scans onto a light board and examined them with the meticulousness of a man who clearly enjoyed his work. ‘There’s no edema of the brain tissue, which is good news, but we are going to carry on monitoring you for signs of change in your neurological status. The main ingredient for your recovery, however, is rest and quiet. How does that sound?’

Holly put her hands on the arm of the chair and found a loose thread to play with. She was chewing gum slowly as if the act itself required a huge amount of concentration.

‘Nice.’

‘How’s your memory these days?’

‘Sometimes I forget why I went into a room, but I think that’s normal.’

‘It’s not.’

‘For me it is.’

He nodded slowly, eyes unblinking

‘Are you drinking alcohol at all?’ he said.

‘Haven’t had a drop for weeks. Months probably.’

‘Good. Best to avoid alcohol at this point in your recovery.’

‘Of course.’

He closed her file with a flick of his wrist.

‘You’re as fit as a fiddle,’ he said.

‘Thank you, Doc.’

‘But we should do more tests.’

She changed out of the gown and into something more befitting a resurrected corpse. A black Cashmere sweater, blue jeans, a pair of low-heeled shoes and a touch of make-up. As she was making her way to her car she was surprised to see DI Bishop waiting outside. She shot him a shadow of a smile.

‘Realised you couldn’t live without me?’

‘Something like that. What did the doctor say?’

‘Says I’m fucked up.’

‘Christ, I could have told you that.’ He took a moment. ‘You want to go for a drive?’

She hesitated by her car door. Had to ask:

‘Is this the new case?’

He stared at her. Gave nothing away.

‘Keep me company.’

Travelling through late afternoon London traffic, the car journey was slow. They went north over Tower Bridge, the Tobacco Dock on their right and Aldgate on their left, dominated by dozens of the high-rise insurance companies and banks.. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...