- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

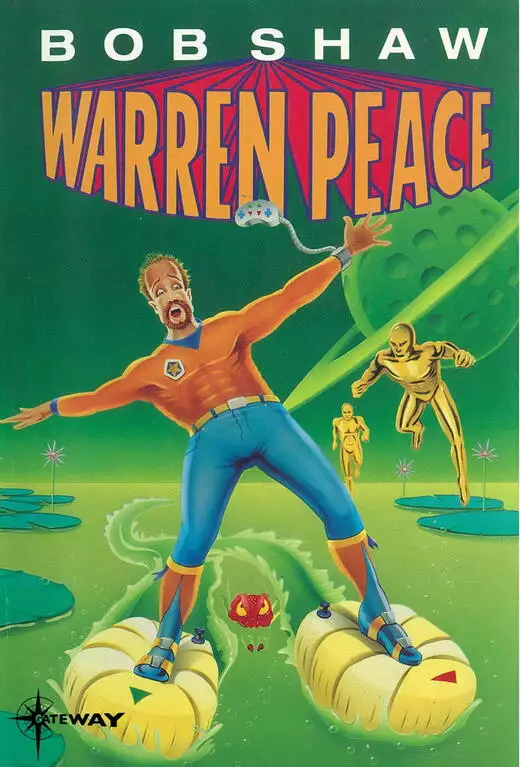

A humorous science-fiction novel featuring Warren Peace, first encountered in "Who Goes Here?". Warren embarks on a new career as a galactic troubleshooter. His first mission takes him to a water planet where a company producing a mind-blowing drug is having trouble with its alien workforce.

Release date: July 15, 1993

Publisher: Gollancz Ltd

Print pages: 320

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Warren Peace: Dimensions

Bob Shaw

It was the eighth day of the Oscar Galactic Jamboree, and he was supposed to be having the time of his life – but the malaise of a bleak, grey, sterile discontent had entered his soul.

There was nothing really new about his having a fit of the blues. In the past, back in the days when he was a human being, he had quite often found himself plunged into a mood of depression. The difference between then and now was that in the old days a number of remedies had been available to him. Depending on his frame of mind, he could dose himself up with vitamin-rich foods; or drown his sorrows in the company of a few congenial boozers; or uplift his spirits by venturing on an exciting new love affair.

Now, however, those paths to happiness were barred to him – for the simple reason that, as an Oscar, he had no need for food, drink or sex.

This is terrible, he thought, glancing down in resentment at his gleaming body. It was more than two metres tall and resembled a golden statue of a perfectly developed man. It was also naked – partly because Oscars were impervious to even the most extreme weather, partly because there were no embarrassing protuberances in the region of the groin. When Peace had found himself ensconced in the splendid, indestructible body almost a year earlier he had been delighted, but of late he had come to regard it as a prison.

And it was a prison from which there could be no escape.

‘Hey, Warren!’ The familiar subetheric voice belonged to Ozzy Drabble, one of Peace’s oldest friends among the Oscars. ‘Why are you skulking around here by yourself? Why aren’t you joining in the fun?’

‘What fun?’ Peace said gloomily, turning to face the approaching figure. To human eyes Drabble would have looked exactly like any other Oscar – a bald-headed, ruby-eyed golden giant – but Peace’s superacute vision was able to pick out distinctive lineaments in his face.

‘Are you kidding me?’ Drabble was unable to repress a laugh as he gestured towards a group of Oscars who were sitting around a campfire a few hundred metres away in the deepening twilight. ‘Those characters are still at it! They passed the four-thousand mark a while ago – and they’re still going strong! It’s the funniest thing you ever heard, Warren.’

‘Is it?’ On the first night of the jamboree, eight days earlier, the Oscars by the fire had begun a rousing subetheric chorus of ‘One man went to mow …’ – and they had been singing ever since. Peace had eventually managed to tune them out of his consciousness, but Drabble’s remarks were weakening his mental defences. Suddenly the joyously combined voices came flooding into his mind.

… 4460 men, 4459 men, 4458 men, 4457 men, 4456 men …

‘Old Harry Kurtzle got his numbers all mixed up last night, and they nearly had to start the song all over again,’ Drabble said with an enthusiastic chortle. ‘You should have heard him, Warren. I thought I was going to die!’

‘That seems an appropriate reaction,’ Peace commented.

‘Aw, don’t be like that, Warren.’ A concerned expression appeared on Drabble’s smooth-cast features. ‘You should be joining in the fun. There must be something going on that you can enjoy. How about going back into the relay race?’

Peace shook his head. The jamboree was being held on the planet Mildor IV, a smallish uninhabited world whose surface was entirely covered with rocky desert. On the day he arrived Peace had been persuaded to take part in the relay race, in which members of competing teams had to run all the way round the equator to get back to the starting point and hand over the baton. It had taken Peace three days to complete one circuit of the globe – three days of utter stultification as he pounded across a featureless landscape – and on getting back to the camp he had promptly resigned from the team.

‘Well, how about the pitching competition?’ Drabble went on. ‘You were doing great there, Warren.’

Peace glanced towards another campfire, where a dozen or so Oscars were engaged in hurling pebbles in a generally eastern direction. They had been similarly occupied since the jamboree had begun and, as Oscars never had to sleep, had kept going even during the hours of darkness. The object of the competition was to see who could propel the largest pebble into low orbit. Peace had found the activity almost as dull as the relay race, the single spark of excitement coming when Joby Lorenz had been struck in the back of the neck by a big pebble descending from a freakishly accurate single orbit. Joby had somersaulted for more than a hundred metres across the desert floor before coming to rest, and his companions were still chuckling over the comical expression he had worn when rejoining the group.

‘I’m sorry,’ Peace said. ‘I just can’t work up any kind of interest in chucking rocks into the sky.’

‘At least you could sit by the fire with Hec Magill and me,’ Drabble persisted. ‘We’re roasting wienies and mallows and yarning about the old days.’

‘For God’s sake, Ozzy!’ Peace cried, losing his temper. ‘What’s the point in roasting wienies and mallows when you can’t even eat the flaming things?’

Drabble looked hurt. ‘It’s traditional, Warren. It creates a nice atmosphere.’

‘That’s another point! This is an airless planet – so there’s no atmosphere of any kind, nice or otherwise. Even your campfires are running on bottled gas! And why the hell would anybody in his right mind want to talk about the old days? All that happened to us in the old days was that the Legion kept us half-starved and shipped us to every hellhole in the galaxy and did its best to get us killed!’

‘Those were hard times,’ Drabble conceded. ‘But talking about them reminds you of what a great life you have now.’

‘Great life!’ Peace was no longer able to keep his feelings in check. ‘You call this a life! I’d have been better off if you and Hec had left me to die that day I got hit by the van. I’m sorry I ever became an Oscar.’

‘Warren!’ Drabble took a step backwards, the ruby lenses of his eyes widening in shock. ‘That’s a terrible thing to say – you must be sick!’

‘Oscars don’t get sick, you dummy.’

‘I forgot,’ Drabble said. ‘But there must be something wrong with you, Warren – nobody else has ever had any complaints.’ Drabble paused, corrugations appearing on the brazen skin of his forehead. ‘Maybe the throw rug we put over you was sick.’

Peace considered the new idea for a moment. The throw rugs were an alien life form which had been encountered in the forests of the planet Aspatria. Their name was derived from their blanket-like body form, which had vivid patterns on the upper surface. The underside, consisting of millions of quivering blood-red feelers, had far less aesthetic appeal. The throw-rugs lived in the branches of tall trees, and had the disconcerting habit of dropping on any human who was unwary enough to walk directly below. At first it was thought that any legionary engulfed by one of the bizarre aliens was simply digested by it, but it later transpired that the throw-rugs were not killers. What a throw rug did when it swaddled a man was to enter a symbiotic relationship with him – and the outcome was an Oscar.

Peace had been badly mangled when knocked down by a van, and Drabble and Magill had rushed him to Aspatria. He had been on the point of death when his friends had taken the extreme measure of draping a throw rug over him, thereby saving his life. That had been almost a year ago, and during that time Peace had seemed to be just like any other Oscar – an invincible golden giant, immune to all human weaknesses, dedicated to fighting crime and corruption throughout the galaxy. Now, however, the honeymoon was definitely over.

‘Look, I’m sorry about this, but I have to get out of here,’ Peace said. ‘I’m going to slip away on the quiet for a while. I’m going to go gafia.’

‘Gafia?’ Drabble looked puzzled. ‘What does that mean?’

‘It’s a new acronym I’ve just made up.’ The Oscars had a strange predilection for inventing words which outsiders could not understand, and for reasons Peace could not explain he had a longing to be the originator of at least one in-group expression. ‘It stands for Getting Away From It All, and I hope it becomes part of Oscar-speak.’

‘There isn’t much chance of that,’ Drabble said. ‘It’s a direct contradiction of Oscaring Is A Way Of Life – which we usually shorten to oiawol.’

‘That’s a useless word,’ Peace protested. ‘It makes you sound like you’ve got sinus trouble.’

‘Oscars don’t have sinuses.’

‘I forgot,’ Peace mumbled. ‘And I still don’t like it.’

‘Never mind that,’ Drabble said. ‘Where are you going to go? What will you do with yourself?’

Peace glanced up into the sky, which had turned completely black during the brief conversation, and let his gaze drift from star to star. ‘I’ll go back on duty. There must be somebody out there who needs help, and I feel better when I keep myself busy.’

‘Brown Owl isn’t going to be too happy about this,’ Drabble said. ‘He likes everybody to show solidarity.’

‘Brown Owl will just have to put up with it,’ Peace said carelessly. He had not spent much time with his commander-in-chief, but – even though Oscars were without gender – he was slightly unhappy about serving under a former male who had chosen himself such an odd title.

‘You’ll be on your own if you get into a jam,’ Drabble warned. ‘The jamboree has another six days to run, and the guys won’t want to tear themselves away before the fun is all over.’

‘I won’t get into a jam,’ Peace said confidently. ‘I’m the first to admit that I’m slightly accident prone, but I know I can stay out of trouble for a mere six days. I can do that standing on my head, for heaven’s sake! Six days! Huh!’

He gave Drabble the Oscar salute – circled forefingers and thumbs pressed to the eyes to symbolize vigilance – then turned and strode off towards where he had left his spaceship. The parking lot resembled an industrial estate filled with ugly, prefabricated buildings – which reminded Peace about another of his grievances against life in general. The romantic side of him demanded that a spaceship, especially one dedicated to the fight against evil, should be an aesthetically gleaming spire with a needle prow pointing at the stars.

By contrast, the standard space cruiser was a low-lying metallic rectangle made of coarsely welded steel sheets, 200 metres long and with a small tower at each end. One tower housed a matter transmitter, and the other a matter receiver, and the ship progressed by transmitting itself forward and receiving itself millions of times a second. In that way it could travel at huge multiples of the speed of light without violating any of the laws of relativity.

There was no doubt that the design was superbly efficient. It was also very safe because, as no ship could be regarded as being in one place or another at any given instant, it was impossible for it to be in a collision. The main trouble, as far as Peace was concerned, was that he had dreamed of crusading through the galaxy, in one piece, in a beautiful silver ship – not of being wafted from star to star as a cloud of particles inside a crude steel lunchbox.

He had no trouble locating his own vessel among dozens of identical shape, because his was the only one with shabby and blistered paintwork. Perhaps his first indication that he was not cut out for the life of an Oscar had come when he noticed he did not share their compulsive need to keep everything gleaming like new, no matter how much boring and repetitive drudgery it took.

He entered the ship by the door in the forward tower, activated all its systems and took off at a leisurely speed. The desert, with its sprinkling of orange and yellow fires, sank in the view screens. Although he had escaped the oppressive tedium of the jamboree he was still suffering from ennui and, just to occupy his mind, he decided to try departing Mildor IV along the centre of its conical shadow without using astrogational instruments. He studied the image of the planet, which was mostly in sunlight from his point of view, then directed the ship sideways until all he could see was a vast black disk imposed on fields of stars. When he judged himself to be in the right position he nudged the ship into what ought to be a perpendicular course, then he switched off the drive and allowed it to coast. If his aim had been good he would eventually be rewarded by the sight of an even corona appearing around the planet as its apparent size shrank to less than that of the sun.

‘It’s not as good as that wonderful moment when a beautiful woman first locks eyes with you over the candle flame at dinner,’ he told himself. ‘It’s not even as good as when the waiter is coming towards you with a bottle of decent wine cradled in his arm. It’s not even as good as slipping your fingers under a well-built burger – but it sure as hell beats sitting around a fire with a bunch of overgrown boy scouts.’

Peace incautiously allowed his long-range supersenses to focus on the group who were singing the roundelay and a wisp of unmelodic song drifted into his mind: … 3824 men, 3823 men, 3822 men, 3821 men …

He shuddered, tuned the relentless phrasing out of his thoughts, and settled down to watch the aft view screen. An hour dragged by, then another and another, during which the view on the screen scarcely altered. Peace was beginning to think that his newly invented pastime hardly deserved its generic name when, with shocking suddenness, a voice echoed silently within his skull.

Wimpole! What are you doing with your helmet off?

A moment later came a reply: My head was sweating, boss. These lead helmets is murder. I swear my brains was beginning to cook.

The strength with which the words registered on Peace’s telepathic faculties told him, much to his surprise, that the speakers were quite close. Their proximity was unexpected because a starship’s radio and tachyon beacons normally advertised its presence in any given region of space – and all of Peace’s detectors had remained quiet. He concentrated on trying to glean more information.

Your brains can boil over and spill out through your ears for all I care, the first speaker stated. This is my last warning to you, Wimpole – keep your helmet on!

But the Oscars ain’t likely to pick us up at this range – and, anyways, you ain’t wearing your helmet.

That’s only because I have trained myself not to think when I’m on a mission like this.

There wasn’t no need to train yourself, boss.

Are you trying to be funny, Wimpole? Put your helmet back on and get ready to release the meteorite.

There followed a long silence which suggested to Peace that the men on whom he had eavesdropped had again screened off their brain emanations by means of lead-lined helmets. But on the last word of the exchange, because telepathic communication often went beyond the verbal level, he had picked up a peculiar mental image. It was of an egg-shaped boulder which seemed to emit a shifting purple glow.

Frowning, he bent his mind to the task of interpreting the stray fragment of conversation. It seemed obvious that criminals were sneaking up on the Eighth Galactic Jamboree with the intention of launching an attack. In one respect the plan was a good one, because all the Oscars in the galaxy were supposed to be conveniently gathered into one small area of Mildor IV. That, however, was where the merits of the attack plan ended. It was impossible to kill an Oscar, and any misguided attempt to do so would only result in a battalion of enraged golden supermen descending on the aggressors. Peace did not like to dwell on the outcome, because the strength of Oscars was such that, even when they were doing their best to exercise only reasonable force, wrongdoers tended to come apart in their hands.

Puzzled by the naivety of the unseen attackers, Peace went to the ship’s control console and switched on its full range of detector systems. There was nothing to indicate the proximity of another ship, but that was hardly surprising considering that cheap anti-detection devices were available at Dixons electronic stores on most civilized worlds. Peace turned the instruments up to maximum sensitivity and was rewarded when one of the screens began to register a small body which was travelling towards Mildor IV at 40 km/sec. When he processed the data he found that the speeding body was slightly more than a metre in its major dimension and had a density greater than that of pure uranium.

It was clear that the criminals had launched their weapon towards the assembly of Oscars, but Peace was still unable to make sense out of the operation. No matter what kind of explosion the projectile might cause the Oscars would survive it, and would set off in pursuit in their –

That’s it! Peace thought, feeling the same kind of exultation he usually got on solving a difficult crossword puzzle. Although the Oscars will be unharmed, all their spaceships could be destroyed! The Oscars could be marooned on a backwater planet … it might be a year before they were discovered and rescued … and the forces of organized crime could achieve many of their evil ambitions in only a year or so …

‘Not while I’m on the scene!’ Peace snarled aloud, all his sense of a purpose in life returning with full force. He interrogated the ship’s main computer, then instructed it to put him alongside the missile which was plunging towards the Oscars’ camp site. The operation took less than a minute, thanks to the fact that the ship’s auto-transceiver system of propulsion was not plagued by the age-old problems, such as inertia, associated with Newtonian physics.

He slid aside the door in the forward tower section and saw, less than a metre away, and set against a starry background, a purple-glowing ovoid of chipped and pockmarked rock. Its strange luminescence aside, the object looked just like any other chunk of celestial debris. It was gradually sliding forward with regard to the ship because of a slight mismatch in velocities.

Peace took a firm grip on the doorframe, extended one leg and placed his foot against the rock. At the instant of contact a curious icy tingle ran up his leg and through his body, causing a momentary blurring of his vision, but the effect was too slight to command much attention. Even if the rock proved to be highly radioactive, which was a possibility, it would do no harm to his superhuman constitution.

There are times, he told himself, when being an Oscar is no bad thing.

Gathering all his strength, he drove his leg out straight and propelled the luminous ovoid away from the spaceship. It departed immediately with considerable speed, tumbling as it shrank in apparent size, and within a matter of seconds had dwindled to a point resembling a fading star. Peace waited until it had passed beyond even his long-range perceptions, then went back to the control console and told his computers to advise him of the rock’s current status. The answer was highly satisfactory: the glowing boulder had been guided into a new path which would take it clear of Mildor IV, and from there, with gravitational slingshot assistance, directly into the local sun.

It had been his intention to disappear into the depths of the galaxy, and perhaps live like a hermit until he felt like rejoining the mainstream of life – no matter what the damage to his standing among his fellow Oscars. Now, however, he had a personal triumph to report to Brown Owl, and the prospect of a great deal of egoboo was almost enough to make him change his mind. (Egoboo, an abbreviation of ego boost, was a term which had been invented by the Oscars to describe the great satisfaction that a member of their fraternity derived from seeing his name favourably mentioned in their group publications.) After a moment’s thought, realizing he was beyond normal telepathic range, he switched on the ship’s subetheric communicator and got through to Ozzy Drabble on the special Oscar band.

‘Hello, my old buddy,’ he said cheerfully. ‘This is Warren calling. How are things going?’

‘Things are going great,’ Drabble replied, sounding a little cautious, undoubtedly wondering why Peace had taken the trouble to call him. In the background Peace could hear …4133 men … 4132 men … 4131 men … and was suddenly tempted to break the connection, but his craving for egoboo won the day.

‘Ozzy,’ he said, ‘have you mentioned anything yet to Brown Owl about my taking off on my own?’

‘No. He’s having so much fun in the tunnel-digging competition tha. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...