- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

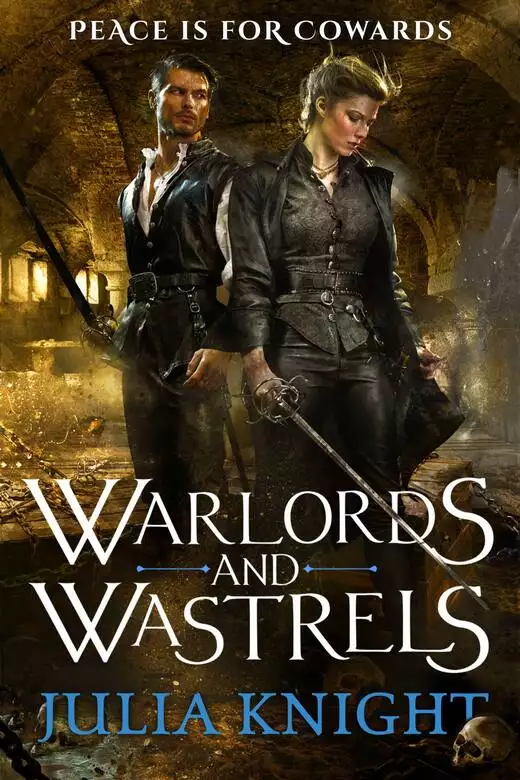

The epic conclusion to the fast-paced new adventure fantasy series, the Duelists trilogy, in the vein of Michael J. Sullivan and Scott Lynch.

Vocho and Kacha may be known for the first swordplay in the city of Reyes, but they’ve found themselves backed into a corner too often for their liking.

Finally reinstated into the Duelist’s Guild for services rendered to the prelate, who has found himself back in charge, Vocho and Kacha are tasked with bringing a prisoner to justice. But this prisoner is none other than Kacha’s old flame Egimont. The prelate wants him alive, and on their side. However the more they discover of Egimont and his dark dealings with the magician, the more Kacha’s loyalties are divided. Soon she must choose a side—the prelate or the king, her brother or her ex-lover.

The fate of Reyes is balanced on a knife-edge.

Release date: December 15, 2015

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Warlords and Wastrels

Julia Knight

Suitably fortified and numb enough that he wouldn’t limp and ruin the effect, he strode along the cloister and out into the damp and misty courtyard ready for sparring practice. Lessers today, first-year students with lots of shiny little faces turning to watch Vocho the Great as he readied himself for the lesson. Just one more reason to keep taking the syrup, he told himself. Vocho the Great didn’t limp or feel fear. He did everything with as much style as he could muster, and he was going to carry on being Vocho the Great if it killed him.

“Right, line up in twos,” he said. “Footwork today, boys and girls, because you lot are a bloody disgrace.”

Vocho the Great wasn’t a natural teacher either. These lessers were so new and clumsy that he despaired. Had he ever been that useless? He didn’t think so. Besides, he should be out doing great feats of derring-do as befitted his name. Not nursemaiding little children and trying to get them to not fall over their own feet when they used a sword, or watching them try not to cry when he raised his voice. He drew the line at wiping snotty noses.

“Cospel! Oh, there you are. Will you do something about that nose over there? It’s making me feel ill.”

Cospel rolled his eyes and advanced on the offending boy, muttering under his breath about “not being paid for this”.

“I don’t pay you to moan either, but you do that all right.”

Truth be told, they were both bored rigid. No to mention this wasn’t their job, not really. It should have been Kass out here. She was guild master–she’d cheated in the duel, he was sure of it, the only way to explain how she’d beaten him, even with his dodgy hip. As such, she should have been herding snotty children and trying to make them into duellists, not him. But after that brief spurt of action to win the title, a few weeks where she’d got stuck in, ordering the guild as she saw fit, grief had finally won, a battle even she couldn’t win. She’d sunk further and further into herself, away from him. Away from life it seemed. And while he didn’t mind helping out, he’d somehow ended up doing pretty much all of the guild master work with none of the prestige of the actual title.

He got the lessers doing a few basic exercises, which they still managed to cock up, and looked up at the outer wall that overlooked the harbour. There she was, again. Watching the ships go in and out like she’d never seen them before, like they hadn’t been brought up on the docks. Watching her like that was one of the subtler pains that the jollop helped with. Every day there she was on a different section of the wall, ghosting along like a wraith. She barely spoke, and answered questions with a wan smile that worried him more and more as time spun on.

Worse, with her turned in upon herself like this, it left him to run the guild. He was making a pretty poor fist of it as well. It didn’t help that he was itching to do a job himself, something where he could shine a bit, help keep up the name. But he and Kass always did their jobs together, everything together, and now she’d left him on his own, even though he could see her up on that wall.

Pining for Petri or not, it was time Kass got out of her own head. He’d tried, Cospel had tried, half the masters, fed up of Vocho, had tried, but she just smiled and nodded and went and sat on the wall. It’d been months now, and something drastic needed to be done before Vocho either murdered the next master who complained about some trivial little thing or drowned in the snot of the lessers. Speaking of which.

“God’s bloody cogs, boy,” he bellowed. “You’re supposed to be a duellist, not a drunken sailor. Have a bit of style. Oh, for the love of… Cospel, will you get that one to stop snivelling?”

After what seemed like about three years, the lesson was over. The lessers scampered out of his bad-tempered way as he stalked out of the courtyard, away from the prying bronze gaze of the clockwork duellist. He’d once fondly thought she looked on him with pride. Just lately the look seemed more of gentle reproach.

He strode down a cloister and through a door, then allowed himself to sag against the wall for a moment. All the twisting and turning, showing the lessers just where to put their feet when they wanted to thrust, to turn an attack, to change a feint into a slash that would cut an opponent in half, all that footwork had taken its toll on his hip. Only one thing would help. He took a look out of a window, at the great clock that towered over the square in front of the Shrive. Not yet. Give it until, say, five o’clock. His hand shook a bit at that, but he told it not to be so stupid and carried on to the guild master’s office. Which was nominally Kass’s but appeared to have been turned over to him, along with all the paperwork that went with it.

His footsteps slowed as he neared the office, and not just because his hip was singing like a tortured choirboy. This was a guild of duellists, men and women who fought, honourably, for pay. It was all about the turn of the blade, the flash of sun off a well-timed attack, the glory and adulation that came with it. Glory and adulation, to his mind, should never involve so much paperwork. There’d been two tottering heaps of it on the desk when he’d left earlier. The Clockwork God alone knew how much there would be when he got back. Sometimes he thought it was his punishment, and he often dreamed about drowning in crackling sheaves of white, black ink flowing down his throat until he choked. He was Vocho the great duellist, not the great bloody signer of papers. It all made him want to lay about with his sword and sweep up the resulting bits later.

Cospel, having got the lessers back to their dorms for now, caught up with him.

“Have you got it?” Vocho asked. He wasn’t sure why he was whispering, given he was supposedly in charge here, but he was.

Cospel brought out a little clockwork gizmo, a fire starter of a newer design that was all the rage. You wound it up and, when you released the catch, two little bronze duellists fought each other in a tiny arena, swords clashing so fast, click-clack-click, it was almost one sound. Each time their blades met, a fat yellow spark would fly off. Unsurprisingly, cases of arson had shot up in the weeks since they’d become popular, to the point where Bakar, the prelate, had instigated a full-time corps for fighting the resulting fires.

“Good,” Vocho said. “I’m going to sort this paperwork once and for all.”

Cospel didn’t say anything to his face, but his eyebrows whirled like disapproving windmills, and there was a certain muttering behind Vocho as he made for the office.

There was a certain muttering in front too as they approached, if anything more disapproving than Cospel’s efforts. Vocho recognised at least two of the voices that drifted out of his office and liked neither of them. His hip twinged in sympathy and he ground to a halt. The limp was back through the numbing syrup, slight but all too noticeable, to him at least. He wasn’t facing what sounded like half the damned guild with a limp. A clock struck in the background, swiftly followed by all the others across the city until the only sound was bells and gongs and the tinkling of inner workings that told everyone who wasn’t deaf, and possibly even those who were, that it was four o’clock.

With a furtive look at Cospel, who was busy muttering under his breath about wages, overtime and days off, Vocho slid his hand into his tunic. One quick snifter, just to settle his hip. Help him deal with the stupid stuck-up bastards he’d been lumbered with as masters. Just a nip. That’s all.

He shut his eyes and waited the few moments before the jollop got to work, then took a deep breath and strode, without a trace of a limp, into the office.

He actually liked the room, when he got it to himself. Large and airy, appointed with only the best–a desk of shining dark wood from Five Islands with a whole host of little drawers, open and secret, plain and booby-trapped, that had kept Vocho busy with his lock pick for the best part of a month. A tapestry from the far-ago time of the now fallen Castan empire, showing some great battle which supposedly the guild had won for the emperor and had led to their currently exalted position. An upholstered Ikaran chest, chased in gold and ivory, a rug made from what was supposedly the hide of a unicorn but which Vocho deeply suspected was, or rather had been, just a very nice horse. A whole collection of swords through the ages from the crude but brutal via the experimental to the springing elegance that was currently in fashion. A splendid view over the docks and, depending on what change o’ the clock the city was on, variously the palace, King’s Row or Bescan Square, with its markets and stalls, truth sayers, storytellers and outright liars. No matter what change they were on, the Shrive still loomed to his left, the great clock in the square before it, but he tried not to look that way if he could help it.

Today he could hardly see the damned window, let alone the view. A master bore down on him from the left, waving yet another bit of paper and bleating about how so-and-so had better rooms than he did–he’d said so last week, and why hadn’t Vocho sorted it immediately? Kass would have done. A second came from the right, one of the dorm masters. She was informing him that Bronze Dorm had a bad case of stomach flux, which was testing the cleaning skills of every maid they had, and that not only would Kass have known what to do, she would have done it without the dorm master having to ask. Another sat back in the chair behind the desk–his chair, damn it, well OK, not exactly but even so. She had her muddy boots up on the shining desk as she drawled on about some of the journeymen who’d been caught selling their nascent services to a street gang from Soot Town, which wasn’t a problem only they weren’t cutting the guild in and did he want her to teach the little buggers a lesson? If Kass had been herself she’d have had her down there a week ago, of course, but Vocho wasn’t quite as good at this guild mastering, she supposed.

Her boots caught one of the towers of papers, sending them scudding over the floor, but she barely even paused. Vocho noted she had some of his best rum in a glass too but didn’t have the chance to do more than open his mouth before another one started, complaining about such-and-such getting all the best jobs, and why wasn’t he getting them, he wanted to know, because everyone knew what an idiot such-and-such was, and just when would Kass be doing something about all this, hmm, because Vocho was obviously not up to the job. Kass this, Kass that. Why aren’t you doing what Kass would? When will Kass start leading this guild properly instead of the hash-up you’re making of it? When is Kass going to start leading this guild? And all in the sort of annoying upper-class drawl that set his teeth on edge.

Later Vocho wasn’t entirely sure what had happened, but the next thing he was aware of was that the woman who’d sat in his chair was on the floor, surrounded by a shower of falling paper, the complainer about so-and-so had a bloody nose, and the one who didn’t like such-and-such was nursing what looked like was going to be a perfect shiner. The dorm master had the reflexes to get across the room fast enough and appeared to have escaped unscathed as she stood by the now half-open window, waiting to see what would happen next. The desk was clear of everything except Vocho’s hands and his sword, and the other masters were staring at him with shock and a simmering anger that would likely boil over later. For now the silence was broken only by the tolling of the god-buoy out in the harbour and Cospel’s sniggers.

“Well,” the dorm master said with a raised eyebrow, “I suppose we can’t expect anything else from you.”

Vocho glowered at her and she had the grace to blush. He took a deep, steadying breath and made sure not to look at Cospel, who was struggling not to laugh. He wasn’t struggling all that hard though, because it kept leaking out like steam from a kettle.

There was a lot Vocho could have said. He could have asked them just how well Kass was doing up on that wall every bloody day. Perfect Kacha wasn’t being very perfect at running this guild now, was she? She wasn’t being guild master at all. But no one seemed to see that, only remembered her as she had been not as she was, and blamed him because he was here and she wasn’t. A lot he could have said but didn’t because he thought Kass had enough of a knife inside her without him twisting it further.

Instead he took a death grip on the desk to avoid lashing out again and a deep breath. “Out, the lot of you. No, I don’t care what he said, or what anyone has done. Out!”

They went, muttering about his lack of manners and breeding, and that Kass would hear of this and more besides. Vocho held on to his temper, barely, until Cospel had firmly shut the door and let loose the laughter that had almost given him a hernia.

“You’re not helping.” Vocho gave the now scattered documents a vengeful kick.

“Maybe not, but we got to take all the laughs we can at the moment,” Cospel said when he’d got his breath back.

Vocho conceded he might have a point and limped about the room gathering the papers into a nice pile in the grate, where Cospel employed his fancy new gizmo and set the bloody things alight. At least it took the chill out of what passed for a Reyes city winter, which mostly consisted of a misty dampness that seemed to seep into Vocho’s hip and make it creak like a clipper in a gale. He lowered himself gingerly into the chair and stared at the flames.

“I’m not sure I can take any more of this. We should be out doing… things! Heroic things! Feats! Tales of great bravery they’ll be talking about a hundred years from now. Saving people, guarding hoards—”

“Getting recognition instead of doing paperwork and listening to moaning minnies?”

“Exactly!”

Cospel slid a sly look his way. “Of course, that means she won, don’t it? That she’d be better at this than you?”

“Normally, I agree–admitting Kass is better at something would be bad. However, this time I’m prepared to let her be better than me.”

“Very magnanimous of you, I’m sure. Thing is, how you going to get her to do the work?”

A good question. They’d all tried. Vocho had talked until he was blue in the face, even Cospel had tried wheedling with that kicked-spaniel look he did so well, but she just shrugged. Some of the masters had tried complaining directly to her and got the same. For all they were happy to tell him how he didn’t compare to her, he knew the masters were running out of patience with her too–there’d been too many whispered conversations that stopped hurriedly if he or Kass came into view, too many looks askance. He needed to do something and soon, or Kass wouldn’t be guild master even in name.

“What we need,” he said now, “is some commission for her–for us. Not just guard duty or anything boring but something to get her teeth into. You know what she’s like about mysteries. They get her all fired up. We need a commission like that, something to engage her gears, get her out of her own head and back into the world. I mean, you know, for her.” Not for his sake in the slightest, oh no.

Cospel poked at the dying flames. “I think we just burned all the job requests.”

“Bugger.” Vocho thought about it some more as Cospel found what was left of the rum and poured them each a glass. There was only one person she might listen to, who might be able to find something to jolt her out of her misery. Vocho told himself he was doing it for her, really. Helping her because she clearly needed it and she was his sister, and he did kind of love her. Most of the time. Maybe he should talk to her again first. He wanted her to be happy, not drifting around the guild like a ghost of the woman she really was.

But a lack of snot in his life would help too.

Six months ago

The freezing rain driving into his face made Petri Egimont’s empty eye socket burn behind the sodden mask that hid it, but that was the least of his worries. Night came early as autumn spun on into winter, and with it came a blazing cold that threatened every bit of him that was exposed. If he wasn’t careful, an eye and the use of a hand weren’t all he’d be without.

The road was drowning in freezing mud, ankle deep and more, dragging at bones that were so weary they felt made of glass. His cloak, such as it was, gave no real protection against the rain that found every crevice and wriggled its bitter way onto his skin. He barely even knew why he was on this particular road, except that it felt like he’d tried every other and had yet to find a place where he was welcome. He’d traded every fine thing he’d had on him when he escaped the city–every trinket, every polished button, even his boots, until all he had left was a shirt, his breeches, the holed shoes he’d traded for the boots and a threadbare cloak that was no match for his old one. Traded them all for a bite to eat, a place to stay. For a surgeon who was so far gone on rum his hands wouldn’t stay still, the only surgeon Petri had been able to afford to cut out the infection that had settled into the wounds on his face, and a mask to cover what was left when he was done. Even with the mask, there was no hiding the ruin of it, or hiding from the reaction it got, which meant sleeping under a lot of hedgerows, in a lot of stables. Weeks spent reeking of mud and horse piss and grinding his teeth.

The Reyes mountains in the coming winter were no place for a man with nothing, not even a pot to piss in. But the plains were full of villages, farms, fields and hedges that people owned and didn’t want him in. A man whose face scared the horses, whose right hand was now useless, who was still learning to use his left, who couldn’t do much of anything to pay his way. A man who dared not say his name because he’d betrayed the prelate, sent him mad, helped plunge the whole country into war. Who was dead, so the newssheets said, and was in any case dead inside. But the mountains were all that were left to him, no matter the stories of robbers and cut-throats and highwaymen, and even that reminder of Kass brought a sharp pain to his chest.

Two ponies trudged past, heads down against the weather, a man bundled up in furs on one, a woman on the other. Petri’s heart gave a lurch, but it wasn’t her. Not Kass. Couldn’t be. Besides, her horse was a deadlier beast than either of those two ponies and doubtless would have taken a chunk out of his leg on the way past. If it had been her what would he have done? Slunk off into the shadows like the coward he used to be or taken out his newly forged rage on her? The old Petri was dead, but he hadn’t discovered who the new one was yet, except he seemed to boil with anger, and that hadn’t helped him much down on the plains either.

The ponies passing him and taking a tiny side track that wound around a sharp fold in the land did show him one thing. If he squinted with his one eye through the rain, past a stand of trees, there was a light. Several lights in fact. What might be a village and maybe, if he was lucky, an inn. One or two innkeepers had taken pity on him, mistaking him for a man wounded in the battle with Ikaras in the summer, whispering with their patrons at his scars, at the accent that marked him. Not pity for long, or for much, but they’d let him sleep in a clean bed, had given him the few jobs they had that he could do to repay them rather than take their charity. Other payments once or twice that he shuddered to recall, dark and sweating and furtive, giving the last, only thing he had to give, leaving him shamed and shameful, torn and tearful, but alive to know it.

But an inn was a good bet–and out of this freezing rain, where he’d die if he stayed much longer. He’d find something to trade, find some job he could do in return for something to eat, a dry place to sleep. Even stables were better than this. Maybe up here in the mountains things would be different.

He turned his numb feet in their holed shoes towards the lights and lurched through the mud after the ponies, hoping only for a warm place.

Light and warmth and the glorious half-forgotten smell of cooking food, of the meaty smell of stew, the yeast of new bread, stopped Petri dead as he stumbled in the inn door. He stood there, dripping freezing rain from his sodden cloak, and savoured it for half a heartbeat.

All he was allowed. The room didn’t go silent, but it did fall to whispers punctuated by the loud laugh of a drunkard in the corner who hadn’t seen him yet. Petri gritted his teeth against the stares, shook out his cloak one-handed–that caused a whole new set of whispers as they saw what was left of the other hand–and swept the rain from his hair, which was just growing back and was now long enough for it to be curled over his shoulder in a way that would mark him as a man of means. Long enough, but he left it wild because he was a man of means no more. The soaked mask had slipped, and he hurried to get it back into place, but the fabric was ruined and with a pang he ripped it off.

In his head he strode serenely towards the bar, ignoring the muttered comments of “Poor bastard” and “God’s cogs, that’s ugly” and “I feel sick” and “Should be ashamed to be out in public.” But numb feet betrayed him, made him stagger, and the need to tell them all to go fuck themselves burned behind clenched teeth.

He curled what was left of a lip at the nearest customer, a heavyset man dressed in a thick smock and loose breeches above mud-caked boots, who flinched back into his chair. Petri didn’t blame him–he’d looked in a mirror once down on the plains and had no wish to look again. His old face was dead, like the old him.

The lump of a man behind the makeshift bar gave him an appraising look from under a heavy brow, but shrugged. “As long as you’ve got coin I don’t give a crap about your face,” the shrug said, which was an improvement on the whispers behind Petri.

“Battle of the Red Brook,” someone said in a voice loud enough to carry and was shushed. Red Brook–or as it had been before so many were slaughtered in it, Smith Brook–fed the Soot Town waterwheels. That battle had taken place not two months ago during the war for Reyes while a regiment of clockwork gods fought off the Ikarans at the front gate of the city. Yet there had still been other battles to fight, and people to fight them. Ikarans had assaulted the brook hoping to breach the walls by Soot Town, and Reyen guards and duellists had defended it even as red-hot blood had fallen from the sky, burning the skin and hair and eyes of Reyens and Ikarans alike. So many had died on both sides that even the ground was stained red now, so they said, and most of those who survived had scars like Petri’s.

He’d been nowhere near Red Brook, though at times he thought it had to have been better than where he was. Most of the survivors had been Ikaran; almost all the Reyens who’d lived had been deserters, and that was where he came unstuck. But up here, so close to the border, where families were Ikaran or Reyen almost by accident, maybe he’d get away with the pretence if he kept his mouth shut, kept his accent behind clenched teeth. He’d always thought more than he spoke, but that had changed, along with a lot else. Down on the plains talk was looser and angrier, and no matter how he told himself to keep quiet, someone would say some bullshit about Eneko, or Bakar, or Kass even, and his once-even temper would explode, for all the good it did him. But up here on the edges of the mountains that had so lately been a bone of contention between Reyes and Ikaras, where laws were something you kept to if you felt like it, things were kept closer to the chest.

“Petri? Petri Egimont, is that you?” A familiar voice came from behind him, shattering any hope he had of staying anonymous.

“Of course it’s him, Berie, you idiot. Petri? Petri!”

They approached on his good side, from a corner where they’d been drunkenly oblivious to his entrance. Now they moved towards him in a flurry of powder and faded silks, hair curled over their shoulders like they were still nobles and ruled Reyes. The whispers about Petri stopped, to be replaced by other words.

“Fucking nobles, ex-nobles more like,” a man said. “More money than brains, and less use than a custard truss. Came up here because they was too scared to fight for Reyes, and now they’re stuck. I’d give ’em coin to bugger off, if I had any.”

Berie didn’t hear or maybe pretended not to–he’d always had a talent for that. He swooped down on Petri like a pigeon after scraps, with Flashy close behind. Petri caught a whiff of fear about their movements. Too sharp, too jerky for these two, who’d raised indolence to an art form. Stuck, the man had said, and it was certain they didn’t fit in this rough inn in the middle of nowhere, with no one of their own imaginary stature. Maybe they’d run out of people to borrow money from.

“Petri, old boy, how the hell are—”

Petri turned to face him with what passed for a smile on his ruined mouth. Berie blanched and staggered back with a very uncharacteristic word. Flashy waved a handkerchief in front of suddenly white lips and swallowed hard.

Nothing for it now. No hope of escaping without talking, revealing what he was, that these scars were not the scars of a hero but more likely that of a Reyen deserter. He could protest he’d been nowhere near the brook, but he’d tried that down on the plain and no one had believed him. So he cranked the smile up a notch and felt the ropes of scar tissue that ended where bare bone began bend and twist.

“About as well as could be expected,” he said. “Under the circumstances.”

A hiss of indrawn breath from behind, a startled curse from further off. Petri had tried but couldn’t get rid of the accent that gave away who he was, or rather what he had once been. Rich, noble, privileged. Hated by all the men and women who’d risen against the king and his favoured few two decades ago. Time changed many things but not hatred, Petri was beginning to understand. Battle of Red Brook or not–and with this accent it would be quite clear not–he was noble, and up here in the mountains things were different. Very different.

A glass smashed behind him, and another. Something metal clonged heavily against wood. Flashy keeled over backwards before anyone had even made a move towards him, while Berie clutched his clinking but skinny purse to himself.

“Them tosspots been up here a while,” the voice behind said slowly. “Throwing around their cash like confetti, acting like they was still lords of the manor, giving people all the more reason to hate ’em. Didn’t peg you for one of them though, not in that get-up. So are you?”

Petri shrugged. “Does it matter?”

“And the Battle of Red Brook?”

Another shrug.

“Here, isn’t Petri the name of that bloke in the newspapers? Didn’t he poison the prelate?”

With that, a bottle flew end over end and smashed on the unconscious form of Flashy. Something shiny slashed at Petri’s good side, but he managed to dodge, barely. It wasn’t going to stay that easy, not with only half his vision and half his hands working. He whipped round and got his back to a wall–at least he cut off one avenue of attack that way. Berie screamed like a child as a rugged set of fists slammed into his face.

“Petri,” he gasped when he could. “Petri, help me.”

Petri grabbed a bowl of hot soup and flung it in the face of the nearest man. Berie would have to fight his own battles because Petri had his hand full with his own.

The evening descended, as it so often did when people saw what was left of his face, heard his voice, into fists and chaos. It was a miracle he wasn’t dead already, but while down on the plains they seemed eager for him to bugger off out of their nice village, they drew the line at killing him, although he sometimes wished they’d get over their scruples and do it.

It looked like he might get that wish here; the mountains were known for their scant regard for the finer points of law. This wasn’t just barroom brawling, not just thrown pint pots and brass knuckles and the cracked ribs that seemed to follow him wherever he went across the plains. The people in this inn were as hard as the rock underneath them, and had knives and swords and even a clockwork gun or two.

Down on the plains Petri hadn’t fought back. What could he do against men and women burly from farming and brave from num. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...