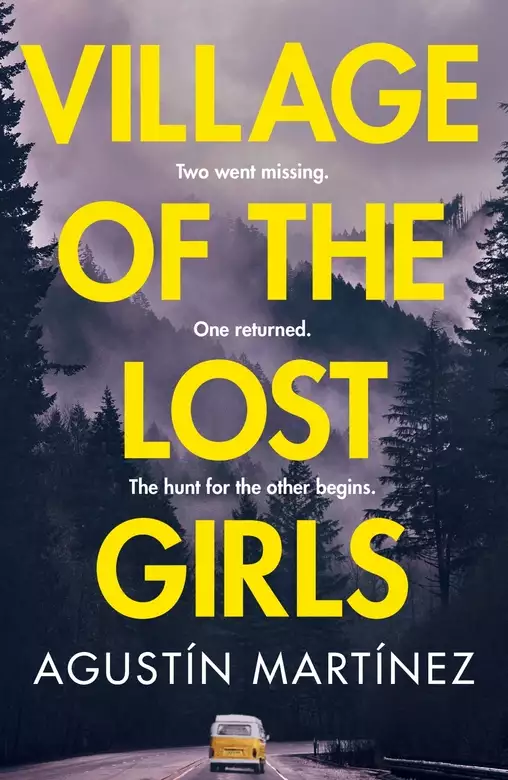

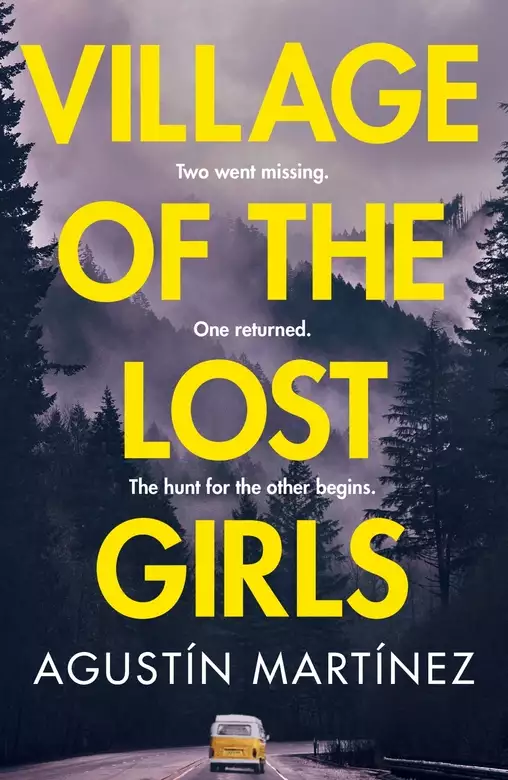

Village of the Lost Girls

- eBook

- Paperback

- Hardcover

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

'Gripping and atmospheric' - Sunday Times A breath-taking missing persons thriller set under the menacing peaks of the Pyrenees Five years after their disappearance, the village of Monteperdido still mourns the loss of Ana and Lucia, two eleven-year-old friends who left school one afternoon and were never seen again. Now, Ana reappears unexpectedly inside a crashed car, wounded but alive. The case reopens and a race against time begins to discover who was behind the girls' kidnapping. Most importantly, where is Lucia and is she still alive? Inspector Sara Campos and her boss Santiago Bain, from Madrid's head office, are forced to work with the local police. Five years ago fatal mistakes were made in the investigation conducted after the girls first vanished, and this mustn't happen again. But Monteperdido has rules of its own. 'Addictive, atmospheric and haunting, one of the best books you'll read this year' - Jo Spain, internationally bestselling author of The Confession

Release date: January 24, 2019

Publisher: Quercus Publishing

Print pages: 416

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Village of the Lost Girls

Agustín Martínez

Her daughter had climbed up a little hill, plunging her hands into the snow to steady herself as she went. The footprints marking her ascent had transformed into tiny black holes. Having reached the top, she tried to stand up without losing her balance, flinging her arms wide and tottering wildly. It looked as though at any moment she would fall and roll down the snowy slope. She was laughing.

Laughing as though she were being tickled.

Her rubber boots sank up to the ankles, giving her enough purchase to be able to bend and scoop up a handful of snow. Excited as a child on Christmas morning, she giggled as she raced to make a snowball. Ana had just turned eleven.

‘They’ll end up getting hurt, you’ll see,’ Montserrat grumbled as she sat down next to Raquel.

At the foot of the snowy hill, Montserrat’s daughter hunkered down, waiting for the impact of the snowball Ana was making. The girls were the same age. They were neighbours. They were inseparable.

‘There’s a lot of snow,’ Raquel said. ‘If they do fall, they’re not going to get hurt. Besides, they’ve got hard heads.’

That morning, as soon as Ana saw that the storm had passed, she had raced into the kitchen and demanded that her mother take her outside to play. Raquel, who had been preparing breakfast, said that she would, though she would have preferred to have stayed at home in the warmth. After they’d eaten, they popped next door. As soon as Montserrat opened the door, Ana had dashed past her in search of her friend, shrieking, ‘Snowball fight!’

A few minutes later, Raquel and Montserrat headed out with their daughters. Wrapped up warm in mittens, woolly hats and puffa jackets (Ana’s was pink, Lucía’s pale blue), the two girls ran on ahead. Two squealing, furry creatures prancing and zigzagging through the snow, heading for the park.

The little hill Ana had climbed was actually the playground slide, buried beneath a snowdrift. From her perch at the top, Ana launched snowballs, trying to make her voice sound deep; she was playing at being an ogre, a fiendish monster. At the bottom, Lucía hid behind bushes that had been transformed into frozen white parapets.

The sky was cloudless, the sunlight glittered on the soft snow and brought a little warmth to Raquel’s face. She closed her eyes and breathed in a lungful of air: cold and clear as a mountain spring. Next to her, Montserrat huddled in her thick coat for warmth.

There was a soft, agreeable murmur. The rustling wind in the trees echoed with their voices and the girls’ shrill laughs. Raquel was in no hurry. She was thinking of the scent of bedlinen, the warmth of her husband’s skin under the sheets as he took her in his arms.

The river rushed on, invisible beneath a thin sheet of ice.

Silent under the mantle of snow, the pulse of the village continued. Steady, constant.

A deer appeared from among the trees that circled the park. Raquel opened her eyes, as though somehow aware of its presence. Snow hung on its antlers, its coat. It took a few steps towards them, oblivious to the girls, unafraid.

‘I can’t believe it,’ Montserrat whispered, watching as it came closer.

Raquel hissed not to make a sound, not to alert the girls. The deer walked over to where they were seated, hooves sinking into the snow, sunlight making its coat shimmer like copper. It looked taller than any deer they had ever seen before. Huge. When it was only a few metres away, Raquel closed her eyes again. She pictured it passing within inches, pausing for a moment to look at her, to smell her. She could feel its breath. As though it were the breath of this mountain village.

When she opened her eyes again, the deer had vanished.

The girls were laughing and throwing snowballs.

She knew that this image would be forever engraved in her mind. That, in time, she would search for it among her memories, as one might seek out the shelter of home.

Eleven-year-olds Ana M. G. and Lucía C. S. left Valle del Ésera School at 5 p.m. last Monday, 19 October 2009, and set off to walk along their usual route to the neighbourhood of Los Corzos, on the outskirts of the village of Monteperdido, in the province of Huesca. Neither of the girls made it home.

‘We are keenly aware that the first 48 hours of an investigation are crucial. We have not been able to do as much as we would have liked, but we will not rest until Ana and Lucía are safely home,’ said a police spokesperson, who denied that there had been any evidence of violence at the site where the girls were last seen, which could lead to fears for their safety.

The parents of the girls have not made a public statement, though a spokesperson for the families has said that they are shocked and deeply concerned. Since their daughters were very familiar with the route home, the parents have rejected suggestions that the girls might have become lost, but have no idea who might have taken them. They firmly hope that their daughters will soon be able to give them answers.

A VILLAGE IN SHOCK

Monteperdido is a well-known tourist spot, famed for its spectacular natural setting, ringed as it is by two national parks in the shadow of the highest peaks of the Pyrenees. Ana and Lucía are well known to local villagers. Both are excellent students and, being next-door neighbours, they are inseparable friends.

Although neighbours are doing everything possible to help with the search, there has been a growing impatience at the lack of any concrete results. No witnesses have come forward; it is as though the two girls vanished into thin air. The Guardia Civil has dispatched a number of officers that specialize in abductions of minors to lead the investigation.

‘We know that it is difficult, but we would ask that people be patient and respect the privacy of the families during this difficult time,’ said one of the recently assigned officers. ‘This is a distressing case, but one that we hope to resolve quickly. In order to do so, however, we need the support of the people in the Monteperdido area, and of the media.’

‘Of course we want to believe that the girls are safe and well. We’re clinging to that hope; it’s what is keeping us going,’ confessed someone close to the two girls. It is a hope shared by everyone in Monteperdido.

The glacier was melting in the summer heat. Ice sheets fractured with a soft crack, and a thin trickle of water spurted from the sheer face of the mountain that towered above the village and gave it its name: Monteperdido – the Lost Mountain.

Some way down the slope, at the bottom of a ravine, the front wheels of the crashed car continued to spin. It lay on its roof, the windscreen a spider’s web of splintered glass, the whole scene enveloped in a cloud of dust and smoke. It had careered over the edge of the dirt road a hundred metres above. The fall had left a trail of broken trees and rutted earth.

Wind whipped away the smoke to reveal a pool of red inside the car, fed by a constant trickle of blood, like water from a leaky tap. The blood dripped from the forehead of the driver, still strapped into his seat belt, now suspended upside down. His skull had been shattered by the impact.

The only sound was the wind and a faint whimper. A girl dragged herself from the wreck, her arms marbled with innumerable thin slashes, her clothes cut to ribbons, a tangle of golden hair falling over her face. As she crawled through the broken rear windscreen, shards of glass became buried in her thighs. She was no more than sixteen. She choked back the pain and managed to pull herself free only to collapse, utterly exhausted. She lay on the grass, her breathing ragged, her whole body shuddering with every breath.

The place where the car had crashed was almost inaccessible: a deep gorge between mountains that were still snow-capped in summer.

Along the rim of the canyon, a narrow road wound its way down to the valley. A four-wheel drive had stopped and a man of about thirty was standing on the edge, staring down into the gorge. He took off his sunglasses to check he had not been mistaken: a car had gone off the cliff. He rummaged for his mobile phone in the glove compartment and made a call.

*

For five years now, the churchyard of Santa María de Laude in Monteperdido had held memorial events for the missing girls. In the early days, it had been the meeting place for the families and their neighbours in the village, for the forest rangers and the journalists. Makeshift shrines were set up next to the church doors, with flowers, stuffed toys, messages . . . Everyone wanted to leave some token of their grief, their anger . . .

Víctor Gamero, a sergeant with the Guardia Civil, remembered that the journalists had been the first to disappear. Although, at the time, he had merely been a junior officer with the force in Monteperdido, he had been responsible for shielding the families from the milling crowds who came from other villages to take part in the search for Ana and Lucía.

Lucía’s father, Joaquín Castán, was angry and frustrated. There were only neighbours from Monteperdido now, and not even all of them. Too much time had passed, the village could not simply grind to a halt every time Joaquín decided to hold another meeting to further the investigation. Two huge photographs of the girls flanked the table at which the parents were sitting. Lucía, with almond eyes and a mischievous smile, looked as though she had been caught in the middle of some private game. Ana, with her mouth open, was flashing a gap-toothed grin. The summer sun had given her skin a golden glow, and her blonde hair was bleached almost white and contrasted with her deep, dark eyes. The girls had been happy when these pictures were taken, yet today, as Lucía’s father protested at the scant resources being allocated to the police investigation, the photographs of the girls looked sad.

Sergeant Víctor Gamero felt his phone vibrate and stepped away from the churchyard to take the call. Burgos, one of his officers, explained the situation, tripping over every word. He knew that no one would be happy with the news.

‘Why didn’t someone alert me? Who gave the order?’ Víctor said.

He had a right to be informed. He was the senior officer of the Guardia Civil in Monteperdido, and the only road into the village had just been cordoned off without his permission.

*

Assistant Inspector Sara Campos gave the officer his orders. He was to stop every vehicle entering or leaving Monteperdido, search the boot of every car, the rear of every van. No one – however well he knew them – was to be waved through. Burgos was irritated by this last suggestion.

‘When I wear this uniform, I’m a Guardia Civil to everyone, even my own mother,’ he protested.

‘Have you alerted the duty sergeant?’ she said, ignoring the officer’s affronted dignity.

‘I just called him. He’ll be waiting for you at the petrol station on the outskirts of the village,’ Burgos said, still bristling.

Sara turned on her heel and walked back to the car where Santiago was waiting. An icy wind rushed down the mountain, so she pulled on her black fleece jacket, zipped it up and buried her hands in the pockets, her dark brown hair fluttering wildly in the brisk wind.

Inspector Santiago Baín kept the engine idling as he waited for the officers to remove the barriers blocking the road to Monteperdido. He could have spared himself the journey, could have called ahead and told the families to meet him at Barbastro Hospital, but he wanted to observe their reactions in the village, give them the news face to face; he knew that the information he was bringing was not a conclusion, but the first line of a story that was yet to be told.

The passenger seat was piled with papers and case files – it was impossible for Sara to squeeze in – so, careful not to disturb the pile, she set it on the dashboard.

‘I just hope he follows orders and checks the boots of the cars,’ she said pessimistically. ‘I don’t think he likes the idea of questioning his neighbours.’

Burgos lifted the barrier and allowed the car to pass. Baín pulled away, heading down the narrow road towards the village. Though it was still early, the sun had already begun to dip behind the mountains. The road ran parallel to the River Ésera, which snaked through a deep ravine between the soaring central Pyrenees, which cast a deep shadow over the whole valley. Though the road climbed steeply uphill, around treacherous hairpin bends, still the mountain peaks towered over the landscape. From time to time, the setting sun flashed through the branches of the trees, staining their vivid green leaves a dusky pink. For a moment, Sara allowed herself to soak up the verdant scene, blossoming with life this 12th July. Standing on a high crag, a deer seemed to be watching the car, then, in an instant, it turned its head and bounded into the trees.

Sara smiled and picked up the mountain of paperwork she had set down on the dashboard.

‘Right, so Lucía’s parents are Joaquín Castán and Montserrat Grau, forty-seven and forty-three respectively. Aside from Lucía, they have another child, Quim, who would be about nineteen at this stage . . . Joaquín Castán has been the driving force behind the Foundation . . .’

‘I think I’ve seen him on TV a couple of times,’ Santiago said, not taking his eyes off the road.

‘Ana’s mother is Raquel Mur. She’s a little younger. Just turned forty.’

‘And her father?’

‘There is no current address for him on file.’ Sara leafed through the documents, desperately looking for the information. ‘The whole investigation was a disaster. No wonder the girls were never found. Roadblocks weren’t set up until seventy-two hours after their disappearance; no evidence was gathered from the place where they were abducted; by the time forensics were called in, the rain had washed away every trace . . .’

Inspector Baín was not surprised; he was familiar with how Guardia Civil operated in rural villages like Monteperdido. He had worked with them on other cases during his long years in the service – almost thirty-five years. ‘So, Ana’s parents are separated?’ he asked.

‘Yes, to all intents and purposes, though they were never legally separated. The father, Álvaro Montrell, was the only person arrested during the whole investigation, and he was only in custody for a couple of days. They clearly had no concrete evidence to hold him. I’m guessing the marriage unravelled after that.’

Sara looked up and saw that Santiago had put on his driving glasses.

‘You’re really handsome in those glasses,’ she mocked.

‘As soon as light starts to fade, my eyesight is shot to shit . . . What do you expect me to do? Do they make me look old?’

‘No older than you are.’

‘One of these days, you’ll be my age, and you won’t find it remotely amusing when some rookie officer makes fun of your presbyopia.’ Santiago Baín smiled.

Sara looked at her boss. His face was lined with wrinkles, but that was not about age. Or at least not entirely. He had had them ever since Sara first met him and, thinking back, she remembered the image that had sprung to mind when she first set eyes on Inspector Baín’s wrinkled face: a chickpea.

Both officers fell silent, intimidated by the landscape as the road wound through the foothills of two imposing mountains. The majority of Pyrenean three-thousanders were in this section of the mountain range, which was one of the factors that had made the original investigation so difficult. When she raised her head from the dossiers, it looked to Sara as though they were approaching a dead end; the tarmacked road seemed to stop at the base of the mountain, never reaching the village hidden on the far side. Monte Albádes and Pico de Paderna towered like colossal statues, like two immortal guards who decided who should pass. As they rounded the last bend, Sara saw the road disappear into Monte Albádes. They took the narrow tunnel that ran through sheer rock like a needle through fabric, and, when they emerged on the other side, what the tourist brochures called the ‘Hidden Valley’ was spread out before them.

On the horizon, she could just make out the village of Monteperdido. Dark, silent houses were punctured by yellow windows, now that the sun had set. To Sara, the houses looked as though they had not been built by men, but rather had been shaped by nature, by seismic shifts and centuries of erosion, like the sierra all around.

A sign by the roadside gave a name to the stretch of mountain they had just come through: FALL GORGE.

‘I don’t know where I went wrong,’ Baín joked. ‘The rookie officer usually has to drive.’

‘You picked the wrong partner. The day I finally got my licence, I swore I’d never get behind the wheel again.’

‘So what will you do when I’m not around?’

‘Plod on.’

Up ahead, on the right-hand side of the road, stood the service station – though in fact it was just a single petrol pump. The Guardia Civil four-wheel drive was parked on the forecourt. The headlights were on, picking out the silhouette of someone standing in front of it. By now, it was pitch dark. As Sara was about to get out of the car, Santiago stopped her.

‘Just this once, let me do the talking.’

She noted that he was trying to sound offhand, as though this was a throwaway remark, when actually he had been waiting for the right moment to say it.

‘Why?’ she asked, feeling like she had done something wrong.

‘Because I’ll want you to deal with the local Guardia Civil from here on. Let them know who’s in charge.’

‘But you usually like to play bad cop,’ she protested meekly.

‘I don’t have many years left in the service; I’d like to play good cop just once,’ Santiago said, trying to make a joke of it.

Santiago clambered out of the car and Sara watched him walk towards the headlights. He did not usually give orders without explanation. And Santiago had never cared about being nice, especially not to people involved in a case. There had to be another reason. It had to be about her. Santiago was trying to spare her having direct contact with those involved in the girls’ disappearance.

‘Fucking chickpea,’ Sara muttered to herself before finally getting out of the car.

*

Sergeant Víctor Gamero watched as the two officers from the Policía Nacional approached. Five years earlier, specialized officers from the Guardia Civil had led the investigation. He could not understand why the Policía Nacional and the Servicio de Atención a la Familia should get involved now, nor why the road needed to be closed. The officer approaching was an older man wearing a suit. He tucked a pair of glasses into his inside pocket and held out his hand with a warm smile.

‘Inspector Santiago Baín of the S.A.F.’

‘Víctor Gamero, sergeant in charge of Monteperdido Station. What’s going on? If you wanted to close the road, I should have been informed.’

‘Actually, we haven’t closed it, we’ve just set up a checkpoint,’ Baín explained.

‘What for?’

Santiago did not answer but turned to his colleague. She strode across the forecourt, sweeping her hair back into a ponytail. Soft features, not particularly tall, she was wearing jeans and a black sweater that rode up over the gun holstered in her belt.

‘This is Assistant Inspector Sara Campos,’ Baín said.

Víctor held out his hand and Sara hesitated a moment before proffering hers. She looked at him for only a split second before turning to survey the landscape surrounding the village.

‘We need to talk to the families of the two girls,’ she said.

‘Has something happened?’

‘Since we’ve come all this way, I’d have thought it was obvious that something has happened, wouldn’t you?’ she said curtly. ‘You drive, we’ll follow.’

Sara turned and headed back to the car. Víctor choked back his anger as he saw Baín smile; he seemed amused by his pushy fellow-officer.

*

Víctor drove through the village along Avenida de Posets. In the rear-view mirror, he could see the car carrying the S.A.F. officers. When he came to the crossroads, he took the road leading to the Hotel La Guardia and then headed towards the suburb of Los Corzos. He crossed the bridge over the Ésera. He had already phoned Joaquín Castán, the father of Lucía. The public meeting was over and he was back at home. Immediately afterwards, Víctor had called the comandante in Barbastro. Apparently the decision to have the S.A.F. lead the investigation came from high up. All officers were asked to cooperate. Víctor Gamero parked the car outside the parents’ houses, at the very edge of the development. To the rear and on the right-hand side, the duplex belonging to Ana’s parents was surrounded by pine forest. Lucía’s house stood next to it.

*

Sara got out of the car and looked at the semi-detached houses. Although architecturally they attempted to blend with the style of the traditional houses in Monteperdido, with local stone and slate roofs, they were obviously ersatz. It was a recent housing development. The house on the left had a little shrine next to the garden gate. A photo of Lucía ringed with fresh flowers, three weather-beaten stuffed toys and a slate on which were chalked the words 1,726 DAYS WITHOUT LUCÍA. The house on the right had nothing to identify it as the one where Ana had lived. The sergeant from the Guardia Civil approached Sara.

‘Should I get the two families together?’ he said.

Sara saw the door to Lucía’s house open. Joaquín Castán appeared on the threshold. She recognized him from photographs in the case file.

‘Did you tell him we were coming?’ It was not so much a question as an accusation.

‘I was asked to track them down,’ Víctor said sullenly.

Sara glared at the officer and Víctor realized that this was the first time she had really looked at him.

‘We’d like to talk to Ana’s mother first,’ Sara said.

Then she looked past Víctor, towards the four-wheel drive. He followed her gaze; on the back seat, a dog was clearly visible.

‘He’s mine,’ Víctor said. ‘But maybe he’s not supposed to know anything either? Because I’m guessing he overheard what we said at the petrol station.’

Sara flashed a half-smile, only to suppress it as quickly as possible. A warning look from Santiago reminded her of her role: this time, she was the bad cop. She quickly turned and headed towards the house of Raquel Mur so that Gamero would not notice her uncertainty. Before they’d arrived, Santiago had asked her to relay the news. This was not the sort of situation where he felt he needed to spare her.

‘From now on, any decision that needs to be taken, we’ll discuss it first. We need to be on the same page. You understand that, don’t you?’ Baín said, laying a hand on Víctor Gamero’s shoulder. He was young to be a senior sergeant, and Baín felt it would be easy to gain his trust.

*

Raquel Mur came to the door and, finding Sara there, she clumsily buttoned up her shirt, which showed a little too much cleavage. It was a man’s blue, checked shirt that fell to her thighs, revealing her bare legs. It was obvious that she had not been expecting strangers.

‘Sara Campos, from the Family Protection Unit. Do you mind if we come in?’ She held up her warrant card.

Sara stared at the woman’s bare feet as they padded almost fearfully across the parquet floor of the living room. Santiago Baín and Víctor Gamero followed Sara into the house. Raquel was clearly confused; her dark eyes tried frantically to catch Víctor’s, waiting for an explanation. Her legs trembled as she slumped on to the sofa. What can she possibly be thinking, this mother who lost her child five years ago? Sara wondered. She had no desire to prolong the woman’s anxiety. She sat on a coffee table facing the sofa, took Raquel’s hands in hers and smiled.

‘It’s not often we get to give good news,’ she said. ‘We’ve found Ana.’

Raquel Mur felt the air in her lungs congeal, as though her whole body was suddenly crumpling. She gripped the officer’s hands tightly.

‘She’s fine,’ said Sara.

Hot tears welled in her eyes. Raquel Mur said nothing, but felt her lips curve into a smile. She brought her hands up to her face and began to sob.

*

Víctor Gamero led Raquel towards Inspector Baín’s car. She was wearing the same jeans and shirt she had worn at the public meeting in the churchyard some hours earlier. She walked nervously, took a few steps back, as though she had forgotten something, then walked on again. Suddenly, she stopped dead, as if remembering what it was she had forgotten. She looked at Montserrat’s house and whispered to the sergeant: ‘I have to tell Montserrat.’

‘The other officer will talk to her,’ Víctor Gamero said, gently turning her away.

Montserrat was standing at the window that overlooked the front garden. By now, Lucía’s mother must have realized that what was coming was not good news. Joaquín Castán was still standing in the doorway.

Santiago Baín and Sara Campos silently stepped inside, followed by Joaquín. In the living room, Montserrat nervously wiped her hands on a dishcloth, and did not stop until Joaquín gestured for her to sit next to him on the sofa. The walls were a shrine to the memory of their missing daughter: Lucía’s smile beamed down from dozens of photographs that charted her childhood from newborn baby to the age of eleven.

‘A crashed car was found this morning, about sixty kilometres south of here. It had skidded into a ravine,’ Inspector Baín explained. ‘When the call came in to the emergency services, they dispatched a helicopter from Barbastro. The site where the car had crashed could not be reached on foot. By the time the helicopter arrived, the driver, a man in his fifties, was already dead. He was almost certainly killed instantly, but we will have to wait for the autopsy results to confirm this. There was a girl there. She was unconscious, but had suffered no other serious injury. She was airlifted to Barbastro Hospital, where attempts were made to identify her. She was carrying no identity papers, but her fingerprints were in the system. It was Ana Montrell. It was at this point that my colleague and I visited the hospital.’

‘What about my daughter?’ Montserrat murmured.

‘There was no one else in the car.’

‘Maybe she wandered away from the car. What if she is somewhere nearby?’

‘The helicopter scanned the area several times to eliminate that possibility,’ Sara said.

‘She’s dead.’ Montserrat began to sob, unable to think of another explanation for Ana’s sudden reappearance.

‘We have no reason to think that is the case,’ Santiago reassured her, gripping her hand tightly. ‘I know this is hard, but you shouldn’t give up hope. We’ve been searching for your daughter for a long time, but this is the closest we have come in five years.’

‘Who was the driver?’ said Joaquín, stiff and motionless on the sofa, listening carefully to every word the officers said.

‘We haven’t yet been able to identify him. Rescuing the girl was the first priority for the emergency services. At first light tomorrow morning, they will go back to airlift the body and attempt to raise the car . . .’

Joaquín Castán remained silent for a moment. Montserrat was still sobbing quietly. Sara saw Joaquín glance at Baín’s hands holding those of his wife, and then he said, ‘The driver of the car – is he the man who took our daughter?’

Though the police suspected as much, it had proved impossible to access the body in the tangled metal of the wreck. The car had no licence plates, so Sara would need the chassis number in order to identify the vehicle – something it would be impossible to get until the car had been winched up from the ravine.

‘I’m going to drive Ana’s mother to the hospital,’ Santiago said to Sara as they left the house. ‘Ask Sergeant Gamero to take you to the police station and set up an incident room. And see if you can find us somewhere to sleep. We need to be working at 110 per cent tomorrow.’

*

A hotel called La Renclusa stood at the end of the main street, where the houses of Monteperdido began to peter out and the road rose steeply towards the mountains. The best accommodation in the village, Víctor said as he pulled up outside. The four and five-star hotels were higher up, in Posets, or further still, where the road vanished in the hills. A nervous girl with birdlike features led Sara and Víctor to the second floor. She stumbled through a description of the hotel’s facilities, meal times, but Sara was not paying attention. She was staring at this girl, who looked no older than eighteen and seemed as fragile as a porcelain doll that might break at any minute. Her name was Elisa, she said, as she opened the windows that looked out towards the north-east. She talked about the spectacular sunrises over Monte Ármos to be seen from the window. Elisa was pretty, though she wore baggy clothes, as though determined to hide her body.

‘Would you like me to get you some dinner?’ she asked.

‘No, thanks,’ Sara said, ‘I just need the keys to both rooms.’ She looked at Elisa’s long-sleeved blouse and the baggy cardigan and smiled. ‘Does it get cold up here?’

‘It gets a little cooler at night. But it’s mid-July, so it never drops below twenty degrees.’ The girl was a little confused by the question, then, noticing the way the offi

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...