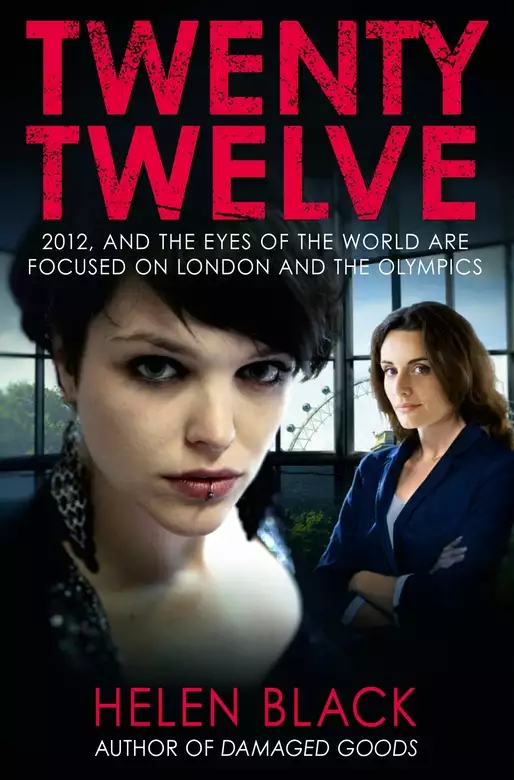

Twenty Twelve

- eBook

- Paperback

- Audiobook

- Hardcover

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

As the UK struggles with a hopeless war in the Middle East, the worst recession in a hundred years and a fraud scandal which has rocked the government to its core, the prime minister is determined to host a summer of top sporting achievement. Jo Connolly, government advisor and dedicated sports fan, is among the thousands eagerly anticipating the Olympic Games and is overjoyed when she is asked to become the poster girl for the Department for Culture, Media and Sport. It's a dream come true, getting heavily involved in the plans for the opening ceremony - until the first bomb explodes...

Release date: April 5, 2012

Publisher: C & R Crime

Print pages: 321

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Twenty Twelve

Helen Black

‘Sweet baby Jesus.’

Officer George Stanley wiped a fat sweaty hand across a fat sweaty face.

‘Go back to the cruiser and get me a beer from the trunk,’ he growled.

Nathan Shaw hesitated. George was the senior officer. Hell, Nathan was barely out of the academy, but drinking on duty?

‘Did you hear me, boy?’ George shaded his eyes against the sun’s dazzle and frowned.

Nathan shrugged and scrambled up the dusty bank to where the cruiser was parked out of view. He popped the trunk and found a plastic icebox nestled between the first aid kit and a carton of surgical gloves. He lifted the lid and let his hand graze the bottles inside. The cold glass was delicious against the pink heat of his skin.

‘Get yourself one,’ George called.

Nathan smiled. One beer wouldn’t hurt. And anyways, who would ever know out here in the August heat? Carefully, he closed the trunk and headed back to George, a Bud in each hand.

George acknowledged him with a nod and reached into his pocket for a bottle opener. ‘Always be prepared,’ he said.

Nathan forced a chuckle and took a long swig. The condensation on the glass had wet his hand and when he lowered himself to the ground, the gritty earth breadcrumbed his thumb, like a chicken tender. He rubbed it against his trouser leg.

‘Goddamn waste of time.’ George held the Bud against his cheek.

Nathan didn’t argue. They’d been here swatting flies and stinking like snakes for six hours straight. He peered at the deserted yard of the Pearsons’ farmhouse. ‘Are they even home?’ Nathan asked.

‘Ain’t no telling,’ said George. ‘Reckon Tobias and the boys left before sun up.’

‘What about the wife? And the little kids?’

George drained the last of his beer with a sigh. ‘Probably inside.’

‘Doing what?’

‘Cooking, praying, who knows?’ said George. ‘And more to the point, who cares?’

Nathan squinted through the white heat at the shutters, bleached by the sun and closed tight. ‘The Chief thinks they might have illegal weapons in there,’ he said.

‘The Chief thinks a lot of things.’

‘You don’t believe it?’ asked Nathan.

George blew across the mouth of his empty bottle, the air making one long sad note. ‘Ain’t about what I believe; it’s about what I know. And what I know is that the Pearsons are God-fearing folk who’ve kept themselves to themselves for the last fifteen years.’

Nathan chewed his lip. George was old school. Voted for Dubya and his daddy before him. If a body didn’t bother him, he saw no reason to bother them. But as far as Nathan could see it, illegal guns and children didn’t have any business being together.

‘I don’t see why we couldn’t just knock on their door and ask ’em,’ he said.

George let out a hoot like an owl. ‘And what would you have done if they didn’t want to talk to you?’

‘Well I don’t know.’ Nathan scratched his chin. ‘I reckon that would have made me suspicious enough to go back to the station for a warrant. To have a look-see around the place.’

‘Uh huh,’ said George. ‘And do you know how to get one of those warrants?’

‘Not rightly.’

‘Let me tell you, boy, they don’t hand ’em out like Christmas cards. You gotta show reasonable cause. You gotta show ev-i-dence.’ George spread his arms out wide, to take in their dusty hideout overlooking the farmhouse. ‘And that is why we are here.’

Nathan turned and scanned the yard once more. In six hours no one had been in and no one had been out. The scene was freakishly quiet.

‘I don’t get it,’ he said. ‘The Chief must be expecting something to happen.’

George pulled at his collar with a doughy finger and breathed a gust of air down the gap.

‘Then answer me this. If there ain’t been nothing happening up here in fifteen years, what makes you think things are going to get crazy today?’

I hate hospitals.

I know everyone says that.

‘It’s the smell.’

Well, of course it’s not.

I mean, I don’t actively like the smell of vomit masked by disinfectant; I wouldn’t, you know, swap my Chanel No. 5 for it. But I don’t loathe it in the way I loathe public swimming pools, or standing in queues, or people who let their dog stick his nose in your crotch and tell you he’s ‘only being friendly’.

If people are honest about what they truly dislike about hospitals, what makes them squirm, it’s the fear of all that pain and death so blatantly and proudly on show. Putting it bluntly, they’re shit scared.

With this cheery thought warming the cockles of my heart, you can imagine how delirious I am as I pull up outside High-fields Hospital for the Elderly and Terminally Ill.

‘Are you my mummy?’

I try not to wrinkle my nose at the old lady in the Winnie the Pooh nightdress and matching slippers.

She bares her hard pink gums at me. ‘Are you my mummy?’

I’m thirty-three and she’s a hundred in her stockinged feet. I try not to be offended.

I look around for a member of staff but, as usual, the place is like the Mary Celeste. Back at reception, three women sit behind a wooden desk festooned with fresh flowers and leaflets urging the aged to eat their five a day. They smile with their straight, white teeth.

‘Welcome to Highfields,’ they trill and direct you to the visitors’ area.

But once inside the belly of this beast, you get neither help nor smiles. Take this poor old lady, for instance; why haven’t her relatives complained? They can’t be happy that she’s left to wander the corridors stripped of her dignity and probably her knickers, can they? But what’s the alternative? Look after her themselves?

Fat tears well in her eyes. ‘Mummy?’

I shake my head and a blanket of hopelessness settles on her shoulders. She opens her mouth in a silent howl. For a second she reminds me of that painting by Edvard Munch.

‘Mummy, Mummy, Mummy,’ she chants, desperately grabbing my wrist in her bent and swollen fingers.

I try to prise her off but she’s surprisingly strong. ‘Could I get some help here?’ I call out.

No answer. Typical. How much does this place cost a week?

At last I spot a familiar figure stumbling out of a side room. He’s more bent than the last time I saw him. He leans more heavily on his walking frame.

‘Dad!’ I wave at him with my free hand. ‘Dad, is that you?’

He shuffles towards me, his breath exploding in raspy puffs. ‘Well it isn’t George bleedin’ Clooney.’

When he finally closes the distance between us, I am startled at the damage inflicted by the last two months in this hellhole. His hair, once thick and curly, is now so thin it barely covers his skull, revealing a smorgasbord of liver spots, moles and itchylooking warts. I berate myself for not visiting more often, for not being a better daughter.

‘What’s the matter?’ He peers at me. ‘Lost my youthful good looks, have I?’

‘You’ve lost weight,’ I reply.

‘If you saw the crap they serve here, you’d understand why.’

I don’t answer. The hospital email me their weekly menu detailing the delicious food on offer: chicken soup. Toad in the hole. Apple crumble.

‘Lord knows your mother couldn’t cook, but she’d make this lot look like Jamie bleedin’ Oliver,’ he says.

I smart at the mention of Mum and want to defend her lumpy cauliflower cheese, but I can’t do another argument. Instead, I nod at the old crone still attached to my arm.

Dad looks at his fellow patient with what might be pity or sorrow and leans in to her ear. ‘Piss off!’ he shouts.

The woman screams and scurries away like a beetle.

I’ve got to hand it to him; even a place like this can’t change my dad.

After the slow march back to Dad’s room, he settles on his bed. Sun streams through his window. In the glare he looks insectile, the thin sticks of his legs held at an odd angle, the skin of his hands as dry and papery as the wings of a dead moth.

He scowls at me. He hates being here as much as I hate visiting. The irony that this place is where he has ended up isn’t lost on either of us. After what he did to Davey, it’s almost a bad joke.

‘So what have you been up to?’ he asks.

‘Not much.’

I’m toying with him. I know what he wants but can’t resist the perverse pleasure of not giving it to him.

He raises an eyebrow, white whiskers sprouting at wild angles like a catfish.

I open my palms as if there is nothing to tell. Why do I do this? Torturing a shell of a man is pathetic.

‘I heard there’s going to be a reshuffle,’ he says.

He looks so eager, like a child waiting for a slice of birthday cake, hoping to get a bit with a sweet on it. The great Paddy Connolly, darling of the party, champion of the hardworking family, enemy of the unions, brought to this. Sniffing out scraps of gossip like a puppy.

I relent. ‘Davison is out.’

Dad nods. ‘About time. The man couldn’t get a hard-on in a brothel.’

‘They say McDonald will get the job.’

‘A move from Education to the Foreign Office.’ Dad whistles. ‘That Scottish bastard always was ambitious.’

I tell him the rest. Who’s in. Who’s out. Who has the PM’s ear. When the old man is satisfied that’s he’s exhausted the detail, he leans back against his pillow. He closes his eyes, so I drop my own little ingot into the conversation.

‘I’ve been offered something.’

His eyes open, instantly alert.

I hold my hand up to calm him. ‘It’s not much. Just a junior appointment.’

‘Everyone has to start somewhere. Even me,’ says the man who became the youngest ever cabinet minister.

I laugh, and for the first time in as long as I can remember he laughs too.

‘So where is it?’ he asks. ‘Health?’

I shake my head.

‘Defence?’ he says.

‘Don’t be daft.’

‘Education?’ He gives a throaty chuckle. ‘Spent some of the best years of my life in Education under Keith Joseph.’

‘It’s Culture, Media and Sport,’ I say.

Dad stops laughing.

‘I guess with my background it seemed an appropriate choice,’ I say.

‘Your background,’ he repeats.

I count to ten in my head. According to Dad, my background is one of politics and power, hailing, as I do, from stock so steeped in the business of government that one of my godparents was the chief whip of the party, the other, Chancellor of the Exchequer.

‘I meant my running, Dad,’ I say.

He blinks at me.

I try to keep the irritation from my voice. ‘I wasn’t bad at it, remember? In the 1996 Olympic squad.’

‘Yes,’ says Dad, but he’s no longer interested.

‘Actually, I’m pretty excited with the Games coming up. I think I can really bring something to the table.’

Dad doesn’t answer. He closes his eyes.

‘Try to eat more,’ I say and make for the door.

I slam the Mini Cooper into third, stamp on the accelerator and barrel down Shooters Hill Road, glad to put Blackheath and Dad behind me.

I can’t believe the old sod still has the ability to make me so angry. I’m a ten-year-old girl again, waving my medals under his nose, only to be asked why I don’t do something more constructive with my time than ‘a bit of bleedin’ running’.

A black cab pulls out in front of me and I press the heel of my hand against the horn. When I spot a tiny gap in the oncoming traffic I hit the gas and overtake, ignoring the cabbie’s proffered middle finger.

‘Your dad’s a hard man to please,’ my mum used to tell me, retrieving the medals from under my pillow.

‘I just want to make him proud,’ I said.

She wiped the tarnished brass against the leg of her trousers and gave me one of her slow, sad smiles. ‘You will, love, you will.’

I thump the side window with the edge of my fist. I refuse to end up like Mum, still trying to do the right thing until the day she died, still dancing to the old bastard’s tune.

She never learned that it didn’t matter whether she did the waltz, the twist or the bloody cha-cha-cha: Dad is never satisfied.

Well, not me. Not any more. I’m hanging up my jazz shoes.

When the leg gave way and all the doctors could do was shake their heads, I didn’t look for sympathy. My running career was over but I got on with my life, didn’t I?

The old man didn’t disguise the fact that he was relieved I’d stop pissing my life away on the track.

‘Mind you,’ he told me, ‘you’ll never make an MP. Too pretty, too indecisive.’

So I joined the civil service.

‘That’s who really run the show.’ Dad winked at me.

And he’s probably right, but I’ve hated every stinking minute of it. The hours, the egos, the backstabbing. Tepid glasses of wine while my smile breaks my jaw.

This job in Culture, Media and Sport is the first thing that has made my blood pump in a very long time. The chance to be involved in the 33rd Olympic Games – here, in London. My town. The chance to reach out and touch, if only fleetingly, something I love.

I force myself to inhale deeply, to exhale through my nose. I will not allow that man to spoil this. The world is bubbling with excitement and I’m going to be at the very heart of it.

‘I am calm,’ I sing out. ‘I am relaxed.’

Shit.

I miss my turn-off for Greenwich and end up in the sludge of Deptford’s one-way system.

Miggs was the last to arrive.

Steve and Deano were already in the kitchen, rooting in Ronnie’s fridge. Deano pulled out a carton of milk and sniffed it. ‘Fucking hell, this is minging.’

He catapulted it into the sink, which was already piled high with greasy dishes and empty takeaway cartons. It landed with a thud, spraying thick white lumps of cottage cheese over the fag ends and cold chips that littered the draining board.

Miggs swallowed down a pang of nausea. He’d stayed in some shitholes in his time but Ronnie’s spot was like a Glasgow crack house.

‘Got any bevvies?’ he asked.

Ronnie didn’t even look up. ‘Cupboard next to the cooker.’

Miggs helped himself to a warm can of Stella and handed out the rest. He wondered why Ronnie didn’t keep them in the fridge, but given the state of it, it was probably for the best.

He took a swig and settled on the sofa where he knew Ronnie slept. A stained sleeping bag lay in a heap in the corner of the room, but the cushions retained the smell of their leader’s sweat.

The TV was already on, though the sound was off. Some twenty-four-hour news channel.

Deano took his place next to Miggs. ‘You want to get yourself a flat screen telly, Ron,’ he said. ‘Much better picture than this heap of shit.’

Miggs caught sight of Deano’s beefy fingers. Between each tattoo, the knuckles were raw and bloody. How many times had Ronnie warned him not to get into any fights, not to draw attention to himself? ‘My brother could get you one for less than five hundred quid. Thirty-six-inch, surround sound,’ he said.

Ronnie shrugged. ‘I’m not really bothered about all that.’

Deano turned to Steve, who was perched on the arm of the sofa. ‘Got you one, didn’t he, mate?’

‘Put my order in.’ Steve flashed the gaps in his teeth. ‘Next day delivery.’

‘See?’ said Deano. ‘As good as fucking Currys.’

Sometimes Miggs couldn’t believe what a stupid cunt Deano could be. Selling knock-off tellies was a sure-fire way to bring the five-oh crashing down on his head. He flicked a glance at Ronnie, looking for the telltale throb at the temples that would signal the shit was about to hit the fan.

Ronnie and Miggs had known each other since they’d been in care. Miggs was originally from the schemes in Possilpark and had been acquainted with a few hard bastards in his time, but nothing prepared him for the brutality of the kickings wee Ronnie would dole out on an almost weekly basis. Miggs had been on the wrong end of a few batterings himself. Umpteen anger management courses and a spell in the madhouse had made no impact. Violence was simply a part of Ronnie’s life.

Luckily for Deano, Ronnie’s attention was diverted by the screen. ‘Turn up the sound.’

Steve leaned forward and punched the remote control. Some bird was standing outside the Olympic Village in Stratford. The breeze ruffled her jacket to reveal the hint of a black bra.

Deano whistled at the screen. Steve joined in. Ronnie put up a hand and silenced them both.

The presenter was smiling into the camera. She had those straight teeth you always saw on the telly but never in real life.

‘An excited crowd is gathered here today to watch the official opening of the Olympic Village, which will be home to more than fifteen thousand athletes from two hundred countries around the globe.’

The camera panned around the village, revealing the rows of spanking new accommodation blocks built around communal squares. A water feature was tinkling pleasantly in the middle. A lifetime away from Miggs’s childhood.

In the distance the five rings of the Olympic flag fluttered.

Miggs risked another sideways glance, but Ronnie’s eyes didn’t leave the screen.

I roar into the car park outside the Village and race over to where the minister is finishing an interview.

Sam Clancy is a consummate performer. When he’s done, he sees me and the smile slides off his face. ‘You’re late.’

‘I had to visit my dad,’ I say.

Sam’s face softens. Even now, Paddy Connolly’s name is royalty. ‘Where are we at?’ he asks.

I pull out my BlackBerry and check my list of things to do. ‘The rooms are completely ready,’ I tell him.

‘You’ve checked the paperwork? We don’t want a re-run of the Delhi fiasco.’

‘It’s all in order,’ I assure him. ‘Building regs, health and safety, you name it. There isn’t a loose screw in the whole place.’

Sam nods in satisfaction. ‘And the Yanks?’

‘All booked on flights and ready for a quick photo op at Heathrow.’

‘The ambassador?’

I pull a face. The American ambassador is never happy. With anything.

‘Still banging on about security, I suppose?’ says Sam.

‘I danced him through every last detail, even the MI5 assessments,’ I say. ‘Short of holding the Games in secret, we can’t make it any tighter.’

Sam cracks a smile. ‘You know what they say, Jo – you can’t please all of the people all of the time.’

As we’re led towards the crowded Plaza, groups of children are pressing their way inside, laughing and pushing one another.

‘Looks like we can please some of the people,’ I say.

Sam gives my shoulder a couple of taps. ‘And that’s what it’s all about, Jo.’

We make our way inside and I can’t keep the smile from my face. The Plaza is fantastic. During the Games this is where the athletes will meet their friends and family, but today we are set up for a conference. Every seat is taken, press and cameramen standing at the sides. I’m glad I wore my new shoes – smart ballerina pumps, the colour of fresh raspberries.

The front row has been allocated to a special school whose pupils have travelled by coach from Bromsgrove so that Sam can make the point that the Paralympics are every bit as important to London as the real deal. A teenage boy with Down’s syndrome is giggling loudly, his round features lit up in excitement. The girl to his right sits low in her wheelchair, clapping.

Their teacher puts a finger to her lips to quiet them but they can hardly contain themselves. It’s infectious and I laugh too.

See, this is what Dad doesn’t get. That politics doesn’t have to be all about arguments and meetings that go on into the early hours.

The Olympic Games are about hope and optimism. They send out the message that we should all strive to be the best we can be. Who wouldn’t want to be involved in that?

Sam takes to the podium. ‘Ladies and Gentlemen, boys and girls, I’d like to welcome you to the 33rd Olympic Games.’

The crowd bursts into spontaneous applause. Even the press corps joins in.

‘I’m sure many of you remember the rapturous news that the UK had been successful in its bid to host the 2012 games. I certainly had a few glasses of bubbly that night.’

A ripple of polite laughter snakes around the room.

‘But after the streamers were cleared away, the reality of the task ahead began to set in.’ Sam lifts a finger. ‘Make no mistake that it has taken years of hard graft and commitment to ensure that everything is ready and in place. It hasn’t been easy. The country has been facing difficult times. We’ve all had our backs against the walls and, to be honest, there have been times when I’ve questioned whether we could pull it off.’

He pauses and lets his gaze sweep across the audience.

‘But ultimately we succeeded because the people of this great country always succeed. We were determined to host a summer of unrivalled sporting achievement which will propel this country into a new era.’

The crowd erupts into cheers and someone throws their cap to the ceiling. The boy with Down’s leaps to his feet and punches the air. He takes two steps towards Sam but security block his path.

‘It’s fine,’ says Sam. ‘We all want to celebrate, don’t we?’ He beckons the boy towards him and every camera in the place begins frantically clicking.

Still grinning, the boy looks behind him to the back of the room. Perhaps his mum is there. ‘I’m here,’ he calls.

I imagine her bursting with pride, snapping away. My mum would have done exactly the same. I hope she’s getting a good view.

Then boom.

A flash of light.

An ear-splitting crack.

Black.

I try to open my eyes but they feel heavy, as if something is weighing them down. I lift my hand to my cheek but I can’t feel that either. Am I dead?

I remember a sea of faces. Clapping. Laughing. A boy with a huge smile. Then nothing.

I try to move but I don’t know if I’m sitting or standing. I can’t feel anything around me. It’s as if I’m suspended. As if all around me is air. Hot air. I break into a sweat.

Christ on a bike, am I in Hell?

I know I’ve been a bit of a twat to my dad, and then there was the time I told that bloke I thought I might be a lesbian so he’d dump me. But are these the sort of sins that warrant an eternal roasting?

I need to open my eyes. I have to see where I am. I let my arms and legs loosen and direct every scintilla of energy towards my face. I control my breathing and concentrate. At last I manage to lift one of my eyelids. Only a tiny slit. But it’s enough.

I see black smoke swirling above me and orange flames snaking towards me like tongues flicking back and forth.

I open the other eye and try to take it all in. Sheets of metal are hanging and swinging like branches in the breeze. Rubble and dust shower down. There are chairs scattered everywhere, mangled and broken.

I try to lift my head, ignoring the pain, and I see it. Through the billowing clouds of smog I can just make it out. A flag. Five rings.

Not Hell, then.

And it all comes flooding back to me. I know that sounds like a cliché but that’s exactly what it feels like. The sights, the sounds, the smells all pour back into my mind, in a raging torrent. Everything mixed up and violent.

Sam was holding out his hand to the boy, urging him to come up to the podium.

The boy, initially so eager, became uncertain. Sam stepped forward.

Then an explosion that seemed to come from miles away and rush at me with the force of a train. It picked me up and slammed me against the wall. It sucked the air from my lungs, squeezing the life from me.

But I’m not dead.

‘What’s happening?’ I call out.

No one answers. I look around me but there’s no one. Where is everybody? ‘Is anyone there?’ I shout.

Only the sound of roaring, like a wild animal, comes back to me.

‘Is anyone there?’ I shout out again.

I . . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...