- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

A Simon & Schuster eBook. Simon & Schuster has a great book for every reader.

Publisher: Accent Press

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Close

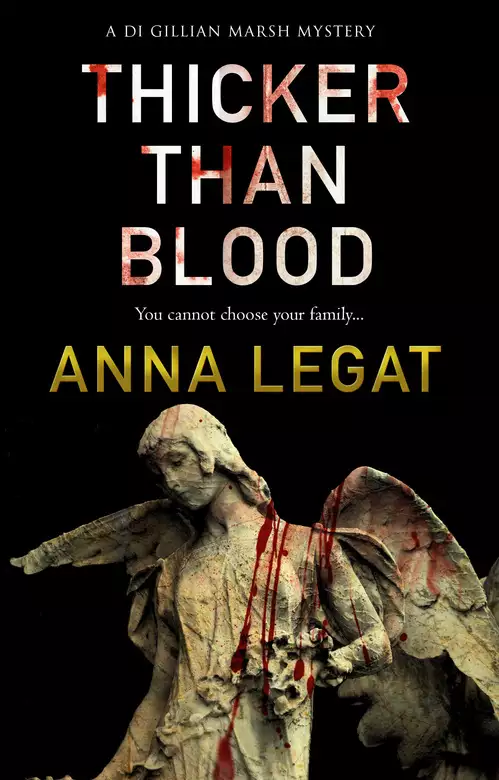

Thicker Than Blood

Anna Legat

PLOUGHING ON

Liam Cox is twiddling his thumbs, willing the priest to take a shortcut to that part where he says, ‘Go forth, the Mass is ended’, the answer to which is quivering on Liam’s lips, ready to come out: ‘Thanks be to God!’

But the priest is taking his time, sending out fumes of frankincense and pronouncing the glory of the Almighty left, right, and centre. Mother must have paid a fortune for this memorial service and she expects good returns on her investment. It will be a while yet. Liam has to grin and bear it. He remembers those long church hours of Sunday Mass stretching into infinity, a purgatory for a small boy with his mind on climbing trees. Today, nearly forty years later, his mind is still on earthly matters, such as his stumbling business. Mother could help, if she wanted to co-operate, but before they get to that he must sit through this spectacle, biding his time. This will please her. ‘Your father will be proud of you,’ she will say, as if Father would have given a toss even when he was alive. Now that he is dead, and has been so for two years exactly, he cares even less. But it matters to Mother. She still believes in all this mumbo-jumbo of praying for the dear-departed in the hope that it will make their afterlife easier.

Oh well, you can take a nun out of a nunnery, but you can’t take the nunnery out of a nun.

‘God, give me strength!’ It is rather hypocritical of Liam to pray for divine intervention under the circumstances of his uncharitable thoughts, but he hopes the loving God will overlook them.

He fidgets, and Mother shushes him, just like she used to when he was a youngster. She puts her forefinger to her lips and frowns at him, whispering, ‘Sit still!’

Liam turns to sit on the other cheek, because the bench is hard as hell and his backside is aching. He catches a glimpse of people on the back benches. Not many people. Maybe ten in all. They are old faces he remembers vaguely from his childhood, faces of no significance now. Right at the back sits a man. He also has a face that is vaguely familiar, but Liam can’t put a name to it. He isn’t that old either: late forties, thick blond hair and beard, Liam’s build. What is he doing attending a mid-week memorial Mass? Who is he? Liam has a strong feeling he should know who that man is.

The priest bellows, ‘Go forth, the Mass is ended!’

‘Thanks be to God!’

When it rains, the freshly turned soil glistens with its own oily sweat. It gives out the scent of musk. It is carnal. Unwashed. Intimate. Mildred loves the smell of ploughed fields in the rain. It makes her feel alive and, at the age of seventy-six, it is a feeling to be cherished. She inhales deeply and holds it in, getting intoxicated on fresh air. Her thoughts ebb and flow inside her skull, the rows of turned earth an extension of her brain waves. She pauses for the hundredth time, and scans the fields. They permeate her. It isn’t so much that she owns them as it is that they own her.

Raindrops crack open against the sou’wester she is wearing over her scarf. It is an old scarf – they don’t make scarves like that anymore. It’s the kind the Queen favours, with a bold floral pattern and a rich, aged-gold border like a picture frame. Her green waterproof anorak keeps her bones warm and dry inside. She could stand here and look at the fields for hours. And inhale them. Mildred sucks in the air greedily. Young people don’t appreciate the simple pleasure of drawing breath, she thinks. They take in air and spit it out without relishing it, like fast food.

‘Mum, we’ve got to be moving. I’ve got millions of things to do back at the office,’ Liam points out with an exasperated scowl. He is a big bull of a man; fleshy, flushed with the effort of walking, already short of breath. And patience. Just like his father, Mildred observes. Reginald too was always annoyed, always had something better to do, something urgent waiting round the corner. He was chasing it relentlessly, like a dog chasing its own tail. He had had no time or patience for Mildred – he simply tolerated her. Nor had he had the time or patience for the land. He had cultivated it without love, without a pause for thought.

‘Mother!’ Liam is talking to a brick wall.

‘Give her a break. She’s catching her breath,’ Colleen tells him.

Mildred smiles at her daughter. In her doe-brown walking boots and a knee-length pleated skirt of demure black under the frills of her exuberantly purple poncho, standing under a green-and-red check umbrella, Colleen is a mismatch of colour and style. Her ripe-plum coloured hair, pinned on top of her head, has fallen out of the bun in thin wisps and is clinging to her neck and cheeks as if the purple hair dye has run. She is puffed and frumpy. She has never cared about her appearance. No wonder she has never married. It used to worry Mildred, but it no longer does.

It is four p.m. Mildred was hoping she could offer them a snack before they left, considering the effort they have made to be here. They didn’t have to come to the service. She half-expected to hear the usual excuses: a dentist appointment, a meeting with a client, the car has gone for service… They surprised her. Seeing them arrive gave her that tiny flutter of motherly pride deep inside her stomach. Liam had even herded in Stella. She stepped out of the car wrapped in a slinky black fur coat, wearing six-inch heels, looking like a penguin on stilts. She used to be a beautiful girl – peachy complexion, slender body. No wonder Liam put up such a fight over her and used every trick in the book to seduce her away from his brother, David. Would he do the same nowadays? He probably would. He is his father’s son. He owns things and he owns people. He won’t let go of what’s his without a fight.

They are standing together. Stella is desperate to squeeze under his umbrella and save both her fur and her hair from ruin. Her narrow heels have sunk deep into the ground and she is leaning forward to maintain balance. An expression of angelic patience graces her face. ‘She’s going to catch her death in this rain,’ she says, unwisely presuming that Mildred can’t hear her. Mildred can, but she is selective about responding. She won’t waste her breath on flippant remarks. She won’t get herself wound up. Sometimes it is easier to pretend she is deaf as a post. That way she can keep track of what is said behind her back.

‘Mother, please, let’s get a move on!’ Liam is such an ankle-biter.

Mildred stirs. ‘Will you stay for a snack and a cup of tea?’ she asks. ‘It won’t take Grace a minute to whip up sandwiches. I have scones and fresh clotted cream. Strawberry jam, homemade…’

‘I’m in, Mum. I’d kill for hot tea. And your strawberry jam…’ Colleen takes her gently by the arm and leads her down the path.

‘Thank God for that!’ Mildred hears Liam mumble under his breath. She is not sure what he is so grateful to the Lord about: the strawberry jam or her being on the move again. His shoes squelch on the muddy ground. Stella’s heels dig into the clay like chisels. When did she become such a madam? She used to live two houses down the lane, on Dove Farm. She used to run about barefoot.

It was his mother’s idea to walk to church. There was the civilised option of taking the car, but she would have none of it. ‘There’s a perfectly good shortcut,’ she’d said. ‘I’d be the laughing stock of Sexton’s Canning being driven five hundred yards in a car! It’s only ten minutes on foot.’ So they went treading through mud and cowpats to please her.

At the gate, Esme is talking to that farmhand – an Irishman whose name Liam never remembers. He became a permanent feature on the farm after Father’s death, or perhaps it was only then that Liam started noticing his sulky presence. All sorts of scum crawl out of the woodwork when a man dies. They feed on hapless senile widows, like ticks on blood.

They are standing by the stables where Esme keeps her horse. Rohan, she calls him. It costs a fortune in insurance. Liam wishes his daughter would spend his money in a more constructive way. But she won’t. She has always been contrary, like her grandmother. Chose to study biology. He asked her why she couldn’t go one step further, become a vet. Push herself a bit. It would give her something concrete in hand, but no! – biology is what she wanted. What do you do with biology? Put your diploma in the bottom drawer and volunteer to do odd jobs for the National Trust; let your father pay the bills.

The farmhand sees them approach, hangs his head low, and disappears inside the stables, taking the horse with him. There’s something shifty about that man! Liam is a good judge of character, and he doesn’t trust him as far as he can spit. He will have to get rid of him. He will have to make lots of changes around here.

Esme is waving, a big smile on her face. She is pretty – strawberries and cream, like her mother used to be at that age. What is she doing talking to that man? What can they possibly be talking about?

‘Sorry, Nan! Couldn’t make it to the service,’ Esme has to bend practically in half to kiss her gnarled grandmother. She is looking guilty. Judging by the fact that she’s wearing her riding boots and jacket, she clearly had no intention of making it to the church.

‘No matter! You’re here now.’ Mother pretends not to be bothered, but she is. It means the world to her – the church, the service, all that hocus-pocus.

‘Was the service good?’

‘It’s a new priest, you see. He didn’t really know Reginald, but still -’

‘He must’ve known him. He’s been here for five years, if not longer. He probably doesn’t stay in touch with his parishioners.’ Stella points out in a tone that implies gross irregularity.

Mother ignores her, or simply can’t hear her. ‘Still, he knew Reginald’s name and got the dates right, and read out the prayer I gave him. He even added a few bits from himself … Good voice – I heard every word he said. Unlike Father O’Leary.’

‘Father O’Leary! His speech was incomprehensible. I couldn’t get past his thick accent and on top of that, he mumbled and grunted… and whistled through his nose. Remember how silly it sounded?’ Colleen chortles.

‘Even when he was young,’ Mildred adds.

‘Was he ever young? I can’t imagine him as a young man.’

‘Now you don’t have to. He died last winter -’

‘Let’s go inside and have that tea,’ Liam butts in, bristling with impatience. “I really ought to be going soon, but there are matters to discuss. Since we’re all here…’

The kitchen is large and airy, as a farmhouse kitchen should be. The pots are hanging high up on hooks under the ceiling where Reginald installed them fifty years ago – now too high for Mildred to reach. Thank heavens for Grace! She is tall and robust. Nothing is ever too high or too heavy for her.

Except that Grace is not here yet. She was going to cycle home after the service, check on the dogs, and come over straight after that. Something must have got in the way. Mildred is disconcerted. She doesn’t know where Grace has put the butter – it isn’t in the fridge. It may be in the larder, but you need a torch to search in there. The torch should be in the top drawer, but isn’t. If she starts opening all the drawers, she will look confused. She most certainly cannot afford to look confused in her own house.

‘I’ll put the kettle on. I say, everyone could do with a cup of tea,’ she says, assertive and competent. Stella stares at her, alarmed by the old woman stating the obvious. She has taken off her fur, folded it inside-out and placed it on the bench next to her. Her hand rests protectively over it, pressing down hard as if the thing was about to come to life and run away.

‘Let me help you,’ Colleen offers and reaches for the bread. She lifts it to her nose and inhales. ‘God, I love the smell of a fresh loaf!’ The sharp knife slides through the crust.

Mildred is picking out the mugs. So many of them are chipped or cracked, or stained inside. Some commemorate Charles and Diana’s wedding. Two of them go back as far as the Silver Jubilee. Eventually she carries five carefully selected mugs to the table, one by one. It is then that she sees the rosebud tea set she washed and dried earlier, ready for tea this afternoon. Flustered, she takes the mugs back to the cupboard. Stella is still staring. Liam has just put down his mobile phone, and is now tapping his fingers on the table, watching her.

Where is Grace?

Mildred succeeds at prising open the tin of tea leaves. With a shaky hand she takes a few scoops, then fills the tea pot with boiling water. Some of it spills out and leaves a wet ring on the bench top, but she carries the pot triumphantly to the table. The milk is definitely in the fridge – she put it there this morning. Mildred pours it into a small jug. The tea is ready. She sits down at the table and feels like bursting into ‘Glory in the Highest’.

‘Mum, where do you keep the butter?’ Colleen’s question makes her heart sink. She doesn’t know where the butter is. And even more to the point, she does not know where Grace is. Where on earth is Grace?

‘Why don’t we wait for Grace?’ she says. ‘She’s in charge of the butter.’

‘Forget the sandwiches, Colleen. We can have the scones instead,’ Stella proposes.

‘I sliced the bread for sandwiches… and the ham looks delicious,’ Colleen looks disappointed.

‘We can have them without butter,’ Esme shrugs.

‘Grace would know,’ Mildred says faintly.

‘I’ll just have the scones. Did Mildred mention clotted cream?’ Stella inquires through the medium of her husband.

Mildred gets up to fetch the jam and cream. The jam is in the cupboard – the bottom shelf – but the clotted cream… It is in the same place as the butter, only Mildred doesn’t know – doesn’t remember – where. She surrenders.

‘I wish Grace was here. She knows where everything is.’

‘Let’s just drink the tea.’ Esme is a good girl.

‘Only I’ve already sliced the bread,’ Colleen insists like a stubborn old mule.

Liam stops tapping the table and points at his mother. ‘This is precisely why you can’t go on like this!’ he bursts out, sweeping his arm around the kitchen as if it was a freak show.

‘Like what?’ Mildred blinks nervously.

‘You aren’t coping. You can’t cope on your own.’

‘Grace is usually here. Something must have -’

‘Grace can’t be here all the time, Mother,’ his tone is placid and patronising, as if he was addressing a five-year-old. ‘If anything – God forbid – was to happen to you, Grace couldn’t cope. Like I said, half the time she isn’t even here.’

‘Not to mention she isn’t a qualified carer,’ Stella adds. ‘Mildred needs professional support.’

Liam glares at her. He dreads what Mother will do. She has this uncanny propensity to dig in her heels just to spite Stella.

She does exactly that.

‘I don’t need a carer – qualified or not. I’m perfectly capable of looking after myself.’

‘She doesn’t even know where anything is in this house,’ Stella goes on, oblivious to the effect she is having.

‘Grace does the housekeeping. I don’t have to know where everything is as long as she does.’

‘Stella, honey, leave it to me,’ Liam fixes his wife with an icy glare.

She snorts, suitably admonished. ‘I don’t feel like the scones anymore.’

‘Why don’t you go outside then? Get some air. Clear that pretty little head of yours.’

‘It’s raining and it’s cold. Why would I want to go outside and stand in the cold?’

‘I really don’t care what you do,’ he grits his teeth, ‘so long as you shut up and stay out of it.’

There is a moment, a glimmer of realisation, when Stella’s lower lip quivers and she swallows the insult loudly and pointedly. She is blinking rapidly, holding back tears.

Suddenly Mildred brightens up. ‘The butter! Grace said she would take it out for us. It’s on top of the fridge,’ she points it out to Colleen. She is a master-evader, avoiding the subject. She may come across as scatty, but she knows what she’s doing.

‘Oh, so it is! Smashing!’ Colleen is overjoyed. Little things make her happy. ‘How many sandwiches? I’ll have two myself.’ No one answers.

‘I feel like such a pig,’ Colleen chuckles. ‘I really ought to lose some weight. I think that’d be my New Year’s resolution.’

‘Mother, I’ve had a good look around residential homes.’ Liam thrusts three spoons of sugar into his tea and stirs frantically. ‘There’s a lovely place in Werton. Grace could visit you every day. We could, too – it’s a ten-minute drive from my office. Mind you, it costs an arm and a leg, but we can afford it if we sell the farm. It’s better to pay a bit more and have peace of mind…’

He reaches for her hand. ‘I’m worried about you, Mother… Here on your own. What if something happens? You see where I’m coming from? At Autumn House they have all the facilities you could ask for: medical nurses, beautiful grounds… You’ll love the gardens!’

‘But I love it here. My farm… I’ve got everything I need. You shouldn’t have troubled yourself, son.’ She squeezes his hand.

Stella snorts again and raises one eyebrow at Liam, as if saying I told you it’d be a waste of breath. He rubs his shiny, well-exfoliated chin, exhales and composes himself again.

‘That’s just the point, Mother: the farm. It’s a business – it has to be run like a business. It’ll go to waste. You can’t run the farm by yourself! I’ve given you two years – just to humour you. To give you time to get over Dad passing, and all that… But without him and at your age, let’s face it, you can’t manage a working farm on your own.’

‘Who said I want to?’

A glimmer of hope lights his eyes. ‘I’m glad you see it this way. We must sell up before it’s run into the ground.’

‘It won’t come to that.’

‘But it will if it isn’t properly managed. It has to go into capable hands, I’ll take care of that. I’ve given it some thought. We have to market it as a going concern, together with the outbuildings and the farmhouse – all as one. So you see, you’ll be so much better off -’

‘I’m not selling.’

‘But I thought we agreed the farm can’t go to waste. We owe it to Father…’

‘The farm is doing well. It is properly managed.’

Liam gawps at her, incredulous. ‘By who? You? You don’t know the first thing -’

‘Sean does. He runs the farm, keeps accounts for me, the payroll – the lot. Grace takes care of the house and the chores. I’m in good hands. Everything is taken care of.’

‘Who the hell is Sean?’

‘Sean! You must’ve seen him around. He’s here from dawn till dusk. In fact, he lives in the cottage. He’s refurbished it – a fresh coat of paint, all the plumbing, patched up the roof. To think that only -’

‘You mean the farmhand? For God’s sake, Mother, we’re talking business management here, we’re talking big money!’

‘We’re talking farming, Dad. He’s good at that, knows his stuff. His family had a farm in Armagh,’ Esme interj. . .

Liam Cox is twiddling his thumbs, willing the priest to take a shortcut to that part where he says, ‘Go forth, the Mass is ended’, the answer to which is quivering on Liam’s lips, ready to come out: ‘Thanks be to God!’

But the priest is taking his time, sending out fumes of frankincense and pronouncing the glory of the Almighty left, right, and centre. Mother must have paid a fortune for this memorial service and she expects good returns on her investment. It will be a while yet. Liam has to grin and bear it. He remembers those long church hours of Sunday Mass stretching into infinity, a purgatory for a small boy with his mind on climbing trees. Today, nearly forty years later, his mind is still on earthly matters, such as his stumbling business. Mother could help, if she wanted to co-operate, but before they get to that he must sit through this spectacle, biding his time. This will please her. ‘Your father will be proud of you,’ she will say, as if Father would have given a toss even when he was alive. Now that he is dead, and has been so for two years exactly, he cares even less. But it matters to Mother. She still believes in all this mumbo-jumbo of praying for the dear-departed in the hope that it will make their afterlife easier.

Oh well, you can take a nun out of a nunnery, but you can’t take the nunnery out of a nun.

‘God, give me strength!’ It is rather hypocritical of Liam to pray for divine intervention under the circumstances of his uncharitable thoughts, but he hopes the loving God will overlook them.

He fidgets, and Mother shushes him, just like she used to when he was a youngster. She puts her forefinger to her lips and frowns at him, whispering, ‘Sit still!’

Liam turns to sit on the other cheek, because the bench is hard as hell and his backside is aching. He catches a glimpse of people on the back benches. Not many people. Maybe ten in all. They are old faces he remembers vaguely from his childhood, faces of no significance now. Right at the back sits a man. He also has a face that is vaguely familiar, but Liam can’t put a name to it. He isn’t that old either: late forties, thick blond hair and beard, Liam’s build. What is he doing attending a mid-week memorial Mass? Who is he? Liam has a strong feeling he should know who that man is.

The priest bellows, ‘Go forth, the Mass is ended!’

‘Thanks be to God!’

When it rains, the freshly turned soil glistens with its own oily sweat. It gives out the scent of musk. It is carnal. Unwashed. Intimate. Mildred loves the smell of ploughed fields in the rain. It makes her feel alive and, at the age of seventy-six, it is a feeling to be cherished. She inhales deeply and holds it in, getting intoxicated on fresh air. Her thoughts ebb and flow inside her skull, the rows of turned earth an extension of her brain waves. She pauses for the hundredth time, and scans the fields. They permeate her. It isn’t so much that she owns them as it is that they own her.

Raindrops crack open against the sou’wester she is wearing over her scarf. It is an old scarf – they don’t make scarves like that anymore. It’s the kind the Queen favours, with a bold floral pattern and a rich, aged-gold border like a picture frame. Her green waterproof anorak keeps her bones warm and dry inside. She could stand here and look at the fields for hours. And inhale them. Mildred sucks in the air greedily. Young people don’t appreciate the simple pleasure of drawing breath, she thinks. They take in air and spit it out without relishing it, like fast food.

‘Mum, we’ve got to be moving. I’ve got millions of things to do back at the office,’ Liam points out with an exasperated scowl. He is a big bull of a man; fleshy, flushed with the effort of walking, already short of breath. And patience. Just like his father, Mildred observes. Reginald too was always annoyed, always had something better to do, something urgent waiting round the corner. He was chasing it relentlessly, like a dog chasing its own tail. He had had no time or patience for Mildred – he simply tolerated her. Nor had he had the time or patience for the land. He had cultivated it without love, without a pause for thought.

‘Mother!’ Liam is talking to a brick wall.

‘Give her a break. She’s catching her breath,’ Colleen tells him.

Mildred smiles at her daughter. In her doe-brown walking boots and a knee-length pleated skirt of demure black under the frills of her exuberantly purple poncho, standing under a green-and-red check umbrella, Colleen is a mismatch of colour and style. Her ripe-plum coloured hair, pinned on top of her head, has fallen out of the bun in thin wisps and is clinging to her neck and cheeks as if the purple hair dye has run. She is puffed and frumpy. She has never cared about her appearance. No wonder she has never married. It used to worry Mildred, but it no longer does.

It is four p.m. Mildred was hoping she could offer them a snack before they left, considering the effort they have made to be here. They didn’t have to come to the service. She half-expected to hear the usual excuses: a dentist appointment, a meeting with a client, the car has gone for service… They surprised her. Seeing them arrive gave her that tiny flutter of motherly pride deep inside her stomach. Liam had even herded in Stella. She stepped out of the car wrapped in a slinky black fur coat, wearing six-inch heels, looking like a penguin on stilts. She used to be a beautiful girl – peachy complexion, slender body. No wonder Liam put up such a fight over her and used every trick in the book to seduce her away from his brother, David. Would he do the same nowadays? He probably would. He is his father’s son. He owns things and he owns people. He won’t let go of what’s his without a fight.

They are standing together. Stella is desperate to squeeze under his umbrella and save both her fur and her hair from ruin. Her narrow heels have sunk deep into the ground and she is leaning forward to maintain balance. An expression of angelic patience graces her face. ‘She’s going to catch her death in this rain,’ she says, unwisely presuming that Mildred can’t hear her. Mildred can, but she is selective about responding. She won’t waste her breath on flippant remarks. She won’t get herself wound up. Sometimes it is easier to pretend she is deaf as a post. That way she can keep track of what is said behind her back.

‘Mother, please, let’s get a move on!’ Liam is such an ankle-biter.

Mildred stirs. ‘Will you stay for a snack and a cup of tea?’ she asks. ‘It won’t take Grace a minute to whip up sandwiches. I have scones and fresh clotted cream. Strawberry jam, homemade…’

‘I’m in, Mum. I’d kill for hot tea. And your strawberry jam…’ Colleen takes her gently by the arm and leads her down the path.

‘Thank God for that!’ Mildred hears Liam mumble under his breath. She is not sure what he is so grateful to the Lord about: the strawberry jam or her being on the move again. His shoes squelch on the muddy ground. Stella’s heels dig into the clay like chisels. When did she become such a madam? She used to live two houses down the lane, on Dove Farm. She used to run about barefoot.

It was his mother’s idea to walk to church. There was the civilised option of taking the car, but she would have none of it. ‘There’s a perfectly good shortcut,’ she’d said. ‘I’d be the laughing stock of Sexton’s Canning being driven five hundred yards in a car! It’s only ten minutes on foot.’ So they went treading through mud and cowpats to please her.

At the gate, Esme is talking to that farmhand – an Irishman whose name Liam never remembers. He became a permanent feature on the farm after Father’s death, or perhaps it was only then that Liam started noticing his sulky presence. All sorts of scum crawl out of the woodwork when a man dies. They feed on hapless senile widows, like ticks on blood.

They are standing by the stables where Esme keeps her horse. Rohan, she calls him. It costs a fortune in insurance. Liam wishes his daughter would spend his money in a more constructive way. But she won’t. She has always been contrary, like her grandmother. Chose to study biology. He asked her why she couldn’t go one step further, become a vet. Push herself a bit. It would give her something concrete in hand, but no! – biology is what she wanted. What do you do with biology? Put your diploma in the bottom drawer and volunteer to do odd jobs for the National Trust; let your father pay the bills.

The farmhand sees them approach, hangs his head low, and disappears inside the stables, taking the horse with him. There’s something shifty about that man! Liam is a good judge of character, and he doesn’t trust him as far as he can spit. He will have to get rid of him. He will have to make lots of changes around here.

Esme is waving, a big smile on her face. She is pretty – strawberries and cream, like her mother used to be at that age. What is she doing talking to that man? What can they possibly be talking about?

‘Sorry, Nan! Couldn’t make it to the service,’ Esme has to bend practically in half to kiss her gnarled grandmother. She is looking guilty. Judging by the fact that she’s wearing her riding boots and jacket, she clearly had no intention of making it to the church.

‘No matter! You’re here now.’ Mother pretends not to be bothered, but she is. It means the world to her – the church, the service, all that hocus-pocus.

‘Was the service good?’

‘It’s a new priest, you see. He didn’t really know Reginald, but still -’

‘He must’ve known him. He’s been here for five years, if not longer. He probably doesn’t stay in touch with his parishioners.’ Stella points out in a tone that implies gross irregularity.

Mother ignores her, or simply can’t hear her. ‘Still, he knew Reginald’s name and got the dates right, and read out the prayer I gave him. He even added a few bits from himself … Good voice – I heard every word he said. Unlike Father O’Leary.’

‘Father O’Leary! His speech was incomprehensible. I couldn’t get past his thick accent and on top of that, he mumbled and grunted… and whistled through his nose. Remember how silly it sounded?’ Colleen chortles.

‘Even when he was young,’ Mildred adds.

‘Was he ever young? I can’t imagine him as a young man.’

‘Now you don’t have to. He died last winter -’

‘Let’s go inside and have that tea,’ Liam butts in, bristling with impatience. “I really ought to be going soon, but there are matters to discuss. Since we’re all here…’

The kitchen is large and airy, as a farmhouse kitchen should be. The pots are hanging high up on hooks under the ceiling where Reginald installed them fifty years ago – now too high for Mildred to reach. Thank heavens for Grace! She is tall and robust. Nothing is ever too high or too heavy for her.

Except that Grace is not here yet. She was going to cycle home after the service, check on the dogs, and come over straight after that. Something must have got in the way. Mildred is disconcerted. She doesn’t know where Grace has put the butter – it isn’t in the fridge. It may be in the larder, but you need a torch to search in there. The torch should be in the top drawer, but isn’t. If she starts opening all the drawers, she will look confused. She most certainly cannot afford to look confused in her own house.

‘I’ll put the kettle on. I say, everyone could do with a cup of tea,’ she says, assertive and competent. Stella stares at her, alarmed by the old woman stating the obvious. She has taken off her fur, folded it inside-out and placed it on the bench next to her. Her hand rests protectively over it, pressing down hard as if the thing was about to come to life and run away.

‘Let me help you,’ Colleen offers and reaches for the bread. She lifts it to her nose and inhales. ‘God, I love the smell of a fresh loaf!’ The sharp knife slides through the crust.

Mildred is picking out the mugs. So many of them are chipped or cracked, or stained inside. Some commemorate Charles and Diana’s wedding. Two of them go back as far as the Silver Jubilee. Eventually she carries five carefully selected mugs to the table, one by one. It is then that she sees the rosebud tea set she washed and dried earlier, ready for tea this afternoon. Flustered, she takes the mugs back to the cupboard. Stella is still staring. Liam has just put down his mobile phone, and is now tapping his fingers on the table, watching her.

Where is Grace?

Mildred succeeds at prising open the tin of tea leaves. With a shaky hand she takes a few scoops, then fills the tea pot with boiling water. Some of it spills out and leaves a wet ring on the bench top, but she carries the pot triumphantly to the table. The milk is definitely in the fridge – she put it there this morning. Mildred pours it into a small jug. The tea is ready. She sits down at the table and feels like bursting into ‘Glory in the Highest’.

‘Mum, where do you keep the butter?’ Colleen’s question makes her heart sink. She doesn’t know where the butter is. And even more to the point, she does not know where Grace is. Where on earth is Grace?

‘Why don’t we wait for Grace?’ she says. ‘She’s in charge of the butter.’

‘Forget the sandwiches, Colleen. We can have the scones instead,’ Stella proposes.

‘I sliced the bread for sandwiches… and the ham looks delicious,’ Colleen looks disappointed.

‘We can have them without butter,’ Esme shrugs.

‘Grace would know,’ Mildred says faintly.

‘I’ll just have the scones. Did Mildred mention clotted cream?’ Stella inquires through the medium of her husband.

Mildred gets up to fetch the jam and cream. The jam is in the cupboard – the bottom shelf – but the clotted cream… It is in the same place as the butter, only Mildred doesn’t know – doesn’t remember – where. She surrenders.

‘I wish Grace was here. She knows where everything is.’

‘Let’s just drink the tea.’ Esme is a good girl.

‘Only I’ve already sliced the bread,’ Colleen insists like a stubborn old mule.

Liam stops tapping the table and points at his mother. ‘This is precisely why you can’t go on like this!’ he bursts out, sweeping his arm around the kitchen as if it was a freak show.

‘Like what?’ Mildred blinks nervously.

‘You aren’t coping. You can’t cope on your own.’

‘Grace is usually here. Something must have -’

‘Grace can’t be here all the time, Mother,’ his tone is placid and patronising, as if he was addressing a five-year-old. ‘If anything – God forbid – was to happen to you, Grace couldn’t cope. Like I said, half the time she isn’t even here.’

‘Not to mention she isn’t a qualified carer,’ Stella adds. ‘Mildred needs professional support.’

Liam glares at her. He dreads what Mother will do. She has this uncanny propensity to dig in her heels just to spite Stella.

She does exactly that.

‘I don’t need a carer – qualified or not. I’m perfectly capable of looking after myself.’

‘She doesn’t even know where anything is in this house,’ Stella goes on, oblivious to the effect she is having.

‘Grace does the housekeeping. I don’t have to know where everything is as long as she does.’

‘Stella, honey, leave it to me,’ Liam fixes his wife with an icy glare.

She snorts, suitably admonished. ‘I don’t feel like the scones anymore.’

‘Why don’t you go outside then? Get some air. Clear that pretty little head of yours.’

‘It’s raining and it’s cold. Why would I want to go outside and stand in the cold?’

‘I really don’t care what you do,’ he grits his teeth, ‘so long as you shut up and stay out of it.’

There is a moment, a glimmer of realisation, when Stella’s lower lip quivers and she swallows the insult loudly and pointedly. She is blinking rapidly, holding back tears.

Suddenly Mildred brightens up. ‘The butter! Grace said she would take it out for us. It’s on top of the fridge,’ she points it out to Colleen. She is a master-evader, avoiding the subject. She may come across as scatty, but she knows what she’s doing.

‘Oh, so it is! Smashing!’ Colleen is overjoyed. Little things make her happy. ‘How many sandwiches? I’ll have two myself.’ No one answers.

‘I feel like such a pig,’ Colleen chuckles. ‘I really ought to lose some weight. I think that’d be my New Year’s resolution.’

‘Mother, I’ve had a good look around residential homes.’ Liam thrusts three spoons of sugar into his tea and stirs frantically. ‘There’s a lovely place in Werton. Grace could visit you every day. We could, too – it’s a ten-minute drive from my office. Mind you, it costs an arm and a leg, but we can afford it if we sell the farm. It’s better to pay a bit more and have peace of mind…’

He reaches for her hand. ‘I’m worried about you, Mother… Here on your own. What if something happens? You see where I’m coming from? At Autumn House they have all the facilities you could ask for: medical nurses, beautiful grounds… You’ll love the gardens!’

‘But I love it here. My farm… I’ve got everything I need. You shouldn’t have troubled yourself, son.’ She squeezes his hand.

Stella snorts again and raises one eyebrow at Liam, as if saying I told you it’d be a waste of breath. He rubs his shiny, well-exfoliated chin, exhales and composes himself again.

‘That’s just the point, Mother: the farm. It’s a business – it has to be run like a business. It’ll go to waste. You can’t run the farm by yourself! I’ve given you two years – just to humour you. To give you time to get over Dad passing, and all that… But without him and at your age, let’s face it, you can’t manage a working farm on your own.’

‘Who said I want to?’

A glimmer of hope lights his eyes. ‘I’m glad you see it this way. We must sell up before it’s run into the ground.’

‘It won’t come to that.’

‘But it will if it isn’t properly managed. It has to go into capable hands, I’ll take care of that. I’ve given it some thought. We have to market it as a going concern, together with the outbuildings and the farmhouse – all as one. So you see, you’ll be so much better off -’

‘I’m not selling.’

‘But I thought we agreed the farm can’t go to waste. We owe it to Father…’

‘The farm is doing well. It is properly managed.’

Liam gawps at her, incredulous. ‘By who? You? You don’t know the first thing -’

‘Sean does. He runs the farm, keeps accounts for me, the payroll – the lot. Grace takes care of the house and the chores. I’m in good hands. Everything is taken care of.’

‘Who the hell is Sean?’

‘Sean! You must’ve seen him around. He’s here from dawn till dusk. In fact, he lives in the cottage. He’s refurbished it – a fresh coat of paint, all the plumbing, patched up the roof. To think that only -’

‘You mean the farmhand? For God’s sake, Mother, we’re talking business management here, we’re talking big money!’

‘We’re talking farming, Dad. He’s good at that, knows his stuff. His family had a farm in Armagh,’ Esme interj. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved