The key to Nancy Jones’s heart dropped through her letter box at 7.35 a.m., as she carefully shared out cat biscuits into five blue saucers. The key fell to the floor with a clatter, a label tied to it with string addressed to ‘Ms Jones, Cat Lady, ref. 38 Evelyn Road, as discussed’. Dressing gown steadfastly knotted, Nancy opened the door a crack, blinking in the sunlight, to see if she could catch the tail of the person who’d delivered it. Nobody was there, but that was no surprise. People didn’t hang around her front garden. Cats did. It wasn’t on the town’s Open Gardens Day programme. Dense and tangled, it was overgrown, with towering holly trees and clumps of thorny brambles like military rolls of barbed wire. Teenagers tossed energy drink cans and Kentucky Fried Chicken wrappers into the long grass. Last winter one person dumped an old mattress and it had taken her two weeks to summon the courage to have it removed.

‘People think this place is derelict,’ the council collection officer had said, while Nancy shivered in her cardigan, releasing a small nervous laugh.

‘What a cheek,’ she’d tried to joke, retreating indoors to find a wall to cling to, blushing with shame. But while it was true the garden was a wilderness and the exterior of the house a little run-down, inside was a slightly better story. She’d moved in thirteen years ago, the town of Christchurch in Dorset chosen from between the starched white sheets of a hospital bed in Northampton.

Walking in through the front door of the house had been like stepping into time forgotten; the house being previously lived in by an old couple who hadn’t lifted a paintbrush since the 1940s. Nancy had hastily viewed the rooms, the forest-green walls, jasmine-patterned wallpaper, chessboard floor tiles and floral curtains blurring into a scene from another century. A grey-and-white cat, with a proud fluffy tail, purring as if playing a tiny trumpet, had convinced her to stay.

Close to Christchurch’s historic quay, where artists painted at their easels near the bandstand, pleasure boats and swans sailed on the water, Norman castle ruins and the Priory church stood alongside a café selling American-style waffles, it was the noise of the seagulls she liked. Their evening chorus was deafening, like a recorder group all blowing into their instruments at once.

She picked up the key and moved to put it in her handbag; she had to get ready for her job at St Joseph’s junior school. Watched by five pairs of cats’ eyes, she glanced at her name on the label. Ms Jones. Years ago, she had been a Mrs, but there wasn’t a shred of physical evidence. The wedding photographer, a friend visiting from Wales who had offered to do the photographs for free, handed her the Kodak film roll after the wedding for developing. She had excitedly put them into the one-hour service at Snappy Snaps, ripping open the packet before leaving the shop. All thirty-six were blank. He had failed to properly close the back of his Pentax camera and light had spoilt the film. She had posted him a bottle of Scotch, and written a note: The photographs are beautiful, thank you so much! The marriage certificate was lost, wedding ring buried in a jewellery box and the off-white lace wedding dress donated to Help the Aged. There must be proof on a register somewhere, locked in a vault in Northampton Registration Office, or had it been shredded since? Nancy tried not to think about that time in her life at all, but memories played on a loop in her mind.

‘Better get dressed, Ted, if you don’t mind,’ she said to the now elderly cat who had first welcomed her to the house. With a splendid white ruff reminiscent of an Elizabethan aristocrat, Ted was phenomenally polite. He stayed perfectly still and closed his eyes, as any gentleman would.

Passing the linen cupboard on the landing – stuffed not with linen, but with boxes full of a life she couldn’t bring herself to look at – Nancy quickly moved into her bedroom and dressed in a long floral print skirt, a cream top and beige ballet pumps. Glancing at herself in the mirror, she wondered at her reflection. Slim, pale-skinned, with a straight nose, large grey eyes, arched eyebrows and high cheekbones, she had once been quite a beauty. Now, she wore no make-up or jewellery. Nothing to draw attention. Her brown hair, streaked with grey, was pulled back from her face with tortoiseshell hair combs. At fifty-six, she searched for her 26-year-old self in the reflection, but she’d been lost on the way. Thumbed a ride on the back of a Harley-Davidson, perhaps, and roared off into a different future.

After calling goodbye and blowing kisses to each of her five cats, she left for work. ‘I’ll love you and leave you and come back later,’ she said to Elsie, her loyal and devoted second-oldest cat, who followed her down the garden path.

Nancy made her way to St Joseph’s, where she worked as a part-time administrator, and took a detour on the way to the address on the label: 38 Evelyn Road. The house was an enormous Georgian property with wrought-iron electric gates that screamed wealth to anyone in the vicinity.

She stood awkwardly, waiting for the gates to open, eyeing a stone statue of a rearing horse by a pond peppered with lily pads. Her shoes crunched on the long gravel drive. A dignified Persian cat, chin raised, was framed in an upstairs window like a portrait of Marie Antoinette. Perfumed wisteria clung to the wall above the glossy black front door and buzzed with fat, rapturous bees. A glint of blue caught Nancy’s eye – there was a swimming pool in the back garden!

She looked through the window to get a closer view, astonished to see a woman slumped on the floor in the hallway, tapping her temples with her fingertips, her back against the wall. The woman’s chestnut hair obscured her features, but Nancy guessed she was in her twenties. Startled, Nancy stepped back and knocked into a planter. Soil spilled out. She yelped. Correcting the toppled pot, she heard a voice from inside the house.

‘Who’s there? If that’s you, Gerard, I meant what I said,’ the woman called. ‘It’s now or never, and I’m rapidly inching towards never.’

Nancy cleared her throat. ‘Oh, hello, it’s… um… I’m feeding your cat this weekend I believe, Mrs… Loveday?’ she called through the door, biting her bottom lip. ‘Your husband – he called into the school and asked if I could cover your long weekend away, so I thought I should come this morn—’

She let her sentence drift. There was an exasperated silence.

‘Oh yes,’ said the woman. ‘But not until tomorrow. Didn’t Gerard give you the dates, for heaven’s sake?’

The woman’s words faded into a strangled sob, which she disguised as a cough. Nancy blushed.

‘No dates, just the key. Shall I come tomorrow then?’ she called, biting her bottom lip again.

‘Yes, tomorrow!’ the woman snapped. ‘We’ll be on the beach in Norfolk by then.’

Nancy’s heart capsized. Of course, she heard the word ‘Norfolk’ often, but it always hit her between the eyes like a flint dagger. She opened her mouth and closed it again. Feeling light-headed, she muttered her mantra: ‘This too shall pass, this too shall pass, this too shall—’ But it was too late. How easily she was knocked off balance.

Retreating from the house, she walked towards the school, trying to focus on her surroundings. The Citroën garage on the corner. Tapper’s Funeral Service, opposite. The neon sign of the Advanced Cosmetic Centre that did laser hair and red-vein removal. The row of terraced houses with pots of red geraniums outside, cars parked nose to tail.

She joined the stream of children walking to school, dressed in yellow T-shirts and black shorts, a thistle in a field of buttercups. With wretched secrets locked in her heart, she gripped the key to another person’s life in her clammy hand.

Bright red blood, the colour of strawberries, oozed from the nose of Alfie Payne, a boy in Year Four. Hovering near the iron railings of St Joseph’s school – a Grade II listed building which had been standing since 1890 and audibly groaned with age – Alfie smudged the blood onto a sleeve of his yellow school T-shirt, his unzipped rucksack at his feet. He was skinny as a blade of grass. Head bowed, he battled not to cry. Nancy’s heart splintered. Squeezing her fingers around the key, she straightened her shoulders and forced all thoughts of Norfolk, and the unsettling sight of Mrs Loveday slumped on the floor at 38 Evelyn Road, into a dark corner of her brain.

‘Nosebleed?’ she asked Alfie with a gentle smile, wondering if, in actual fact, he’d been in an altercation. It wouldn’t be the first time. ‘You might need an ice pack on that.’

Alfie sighed, opened and closed his big blue eyes and gave her an exhausted nod, before spitting a big, bloody globule onto the hopscotch that had been freshly painted on the asphalt. Their eyes met and, despite his obvious distress, he gave her a tiny, rebellious, upside-down smile.

‘It’s not that bad,’ he muttered. ‘I just… banged it.’

‘Let’s find you a wipe so you can get cleaned up,’ Nancy said, her heart still pounding, ‘and a fresh shirt.’

She took another deep breath to slow her racing pulse. Over in the playing field, the rest of the schoolchildren were star-jumping on the sun-scorched grass, in a wake-and-shake exercise session led by the PE teacher. Music blared from speakers and parents stood on the sidelines laden with bags and gym kits and lunch boxes, some wearing enormous sunglasses like spies. The other office ladies were there too, in their glittery sandals, lanyards swinging, holding their sides as they shook with laughter. Nancy felt a familiar pang. She allowed herself to imagine, for the briefest moment, what it must be like to join in. Heart leaping as you unselfconsciously move to the music, shrieking at the silliness of it all, without a single care in the world.

Scanning the field for possible culprits, she caught sight of the caretaker, George, hammering a nail into the roof of the gazebo. George wore a khaki sun hat, the sort a hiker might wear, and lifted it three inches from his head when he noticed Nancy, as if a brass band was belting out the national anthem. George was something of a hero at St Joseph’s. He’d saved a schoolboy from choking to death one lunchtime last April, by hitting him firmly between the shoulder blades and dislodging a cherry tomato from the boy’s throat. The tomato had popped out like a champagne cork, to a communal sigh of relief. A reporter from the local radio station had interviewed him.

‘Anyone with a pulse would have done the same thing,’ George had said to the reporter, batting off the praise, trying to make the extraordinary ordinary. ‘Have you finished? I’ve got work to do.’

He had a weathered complexion and the broad shoulders of a man used to physical labour. Nancy found herself wondering if he had a wife at home to apply sunscreen to the back of his neck or whether he did it himself in the bathroom mirror. The thought made her blush deeply and she stared intently at her skirt. It was coated in cat hair. Ted shed more fur than the others put together – as if he was constantly too hot, like a toddler refusing to wear a coat. She plucked hopelessly at the fluff.

‘Come on in, Alfie,’ she said, opening the school entrance door.

Nancy had learned not to fuss over Alfie. He was a quiet boy, with unkempt hair and eyes like saucers. He moved around the school with his head bowed, as if trying to take up as little space as possible. He lived on the street that ran parallel to Nancy’s, and the bottom of his garden met the bottom of hers, separated by a dilapidated fence which often collapsed in the wind. Nancy knew that Alfie’s parents had recently split up and she had seen him in his garden, swinging on a rusty old swing, which creaked eerily as it moved. There was something dejected about Alfie that made her long to scoop him up in her arms like an injured kitten, take him home for a bowl of ice cream, but she couldn’t do that, not least because of his timidity. Even a direct question asked in the wrong voice could made him scatter, like clapping at a pigeon.

The school reception was quiet and cool, with teachers ducking in and out of classrooms, preparing for the day ahead, an occasional ‘Morning!’ bursting forth in a reassuring, sing-song tone. Nancy felt the tension begin to slip from her shoulders and she reached inside her bag for wipes.

‘Look at my shoe,’ Alfie said, his eyes bulging with enraged tears. ‘The sole is falling off.’ He lifted his left foot, to demonstrate the flapping sole. He had to drag his feet to keep it on, as if he was wearing skis. ‘I wish I was invisible. He emptied my bag and took my crisps.’

‘Who did?’ Nancy asked, trying and failing not to sound too interested. ‘Who took your crisps?’

He stood perfectly still.

‘I don’t remember,’ he said, refusing to look at her. ‘Nobody.’

‘Was it someone from this school?’ she asked gently, passing Alfie a wipe and tissues. ‘Sit down for a moment.’

‘Not this school,’ he said unconvincingly, perching on the edge of a chair in the corridor.

So many things about Alfie seemed to make boys want to pick on him: the wrong hairstyle, no mobile phone, broken shoes. Meaningless things. Nancy wanted to empty the mobile phones and smartwatches out of those boys’ rucksacks – whoever they were – and stamp on them until they were crushed into a million pieces. Would that teach them empathy?

‘Oh, let me check – I think I might have spare crisps,’ Nancy said, suspecting that he had packed only crisps for lunch. The school catchment netted areas from the rich side and the poor side of the town – so the children were an incongruous mix of haves and have-nots. Mr Phillips, the head teacher, was proud of saying the school represented their diverse local community, but Nancy often wondered how the poorer kids felt as they watched their wealthier counterparts eating smoked-salmon bagels and plump, fragrant strawberries for lunch, while they survived on free meals. Not that she begrudged children the right to strawberries. If life had worked out the way it was supposed to have done, any child of hers would have eaten strawberries. Bowls of them. Fields of them.

‘Have these,’ she said, quickly taking a bag of crisps, a cereal bar, an apple and a banana from her own bag and pushing them into his rucksack. It was the least she could do. ‘Your nose looks fine now,’ she said. ‘Do you feel okay?’

He nodded.

‘I can clean your shirt if you like,’ she said. ‘Meantime, let me find you a fresh one. Wait here a moment.’

She let herself into the front office, leaving the door open while Alfie waited on the chair. Placing her bag on her desk, she quickly dug through the lost-property box – mountain-high with abandoned uniform – and pulled out an unnamed yellow shirt. There were black plimsolls in his size in there too, better than the broken shoes he had on.

‘These should fit,’ she said, watching relief rinse through him.

‘Thank you,’ Alfie said, suddenly standing as he caught sight of the gold maneki-neko fortune cat on Nancy’s desk. The Japanese ceramic figurine with a beckoning hand was supposed to bring the owner good luck. Alfie stepped inside the door to get a better look and pointed at a blurry image of Nancy in a copy of the school newsletter also on her desk. ‘Is that a picture of you?’ he asked.

Nancy blushed. The newsletter had been Emma’s idea. The school secretary, Emma, kept the day-to-day life of the school running smoothly, and while she dealt with the snowstorm of pupils, parents and visitors who needed attention, Nancy worked quietly in the wings. Words fizzed out of Emma like she was a shaken can of Vimto. Her life was a soap opera, but though she never stopped talking, Nancy was grateful for her stream of news. It meant she could wordlessly organise the class registers and allocate the wristbands for school lunch, while Emma chatted on. And on. Last month, on a warm Friday evening, Emma had invited Nancy for a drink at the pub with the other girls, and despite part of her longing to accept, Nancy had instinctively invented an excuse.

‘I’m cat-sitting this weekend,’ she’d lied. ‘Sorry. It’s, um, for a neighbour. I can’t let them down.’

‘Urgh cats,’ Frances, personal assistant to the headmaster, who sat alongside Emma and Nancy, had said, dramatically shuddering. ‘I’ve always thought cats are evil. Do you know they steal the breath of a baby while they sleep? I’m one hundred per cent a dog person.’

Nancy had felt her hackles rise. Images played out in her mind. Elsie, her beautiful, loyal tabby cat with deep green eyes and the serious air of the deeply religious, waiting anxiously, velvet white-socked paws neatly together, at the end of the garden path for Nancy’s safe return from work. Ted, sitting on the top of wardrobes and cupboards, keeping watch, like a grey-and-white version of the Queen’s Guard. Tabitha, plump and orange as marmalade, who slept on the pillow spooning Nancy’s head – a living trapper hat. William, dressed in a black-and-white tuxedo, whatever the time of day, straddling his latest kill with muscle-bound shoulders. And finally, sweet Bea, with a patchwork coat of white, brown and black, as if having rolled in paint, always willing to butt heads. They were her everything. They were her family.

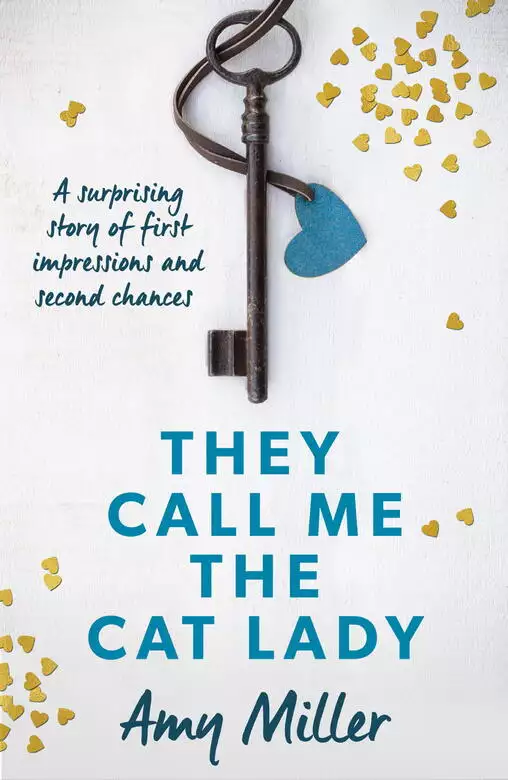

‘That’s horrible.’ Emma frowned, stretching her lips into a grimace. ‘Anyway, perhaps you could take advantage of this, Nancy? Everyone around here already calls you the “cat lady” because you have millions of cats. Not to mention your little friend here.’

Emma pointed a long fingernail at Nancy’s Japanese cat figurine, her words repeating in Nancy’s head. Everyone already calls you the cat lady.

‘Five cats,’ Nancy muttered, knowing Emma wasn’t listening. ‘I only have five.’

‘Five!’ scoffed Frances. ‘Good God, even that’s insane. How can you stand it? All that fur. I’m terribly allergic. Show me a picture of a cat and I’ll sneeze for twenty-four hours straight.’

Frances’s eyes dropped to clumps of fur visible on Nancy’s skirt. She pulled a nasal decongestant from her bag and squirted it up her nose.

‘The very thought makes me shudder,’ said Frances, clasping her hands together. ‘Give me a black Labrador or a cockapoo any day.’

If I had five children, Nancy thought but didn’t say, you wouldn’t bat an eyelid. You’d think I was unremarkable – blessed even.

‘I can whip you up an advert, then if Mr Phillips approves, we can put it in the newsletter, on the board in the staff room, and email the trust staff,’ Emma enthused. ‘I bet plenty of parents need an animal sitter for when they go on their fancy weekend breaks. It’ll be a money-spinner for you and’ – she lowered her voice – ‘get you out and about a bit more. Never know what it might lead to. I don’t like to think of you all alone in that old house of yours. Apparently, my mother was telling me, your house used to be stunning, but the old dear who lived there before you lost her husband then her marbles, and the place went to pot. Shame, isn’t it?’

Nancy imagined marbles spilling from the previous inhabitant’s head, in the hallway of the ramshackle house. Each marble bouncing off to dark corners and mouse holes and cracks in the floorboards. The cats would go wild for them. That poor old woman. Even on her hands and knees she would never have been able to find those marbles again.

She swallowed, knowing what people thought of her. It was obvious in their overly polite smiles, and the speed with which they checked the time and found they had – ohmygod – run out of it. They thought she had lost a few marbles herself. That she was a cat lady who collected cats’ whiskers (she did, as to find one and keep it in your purse meant good fortune), allowed all of her cats to sleep on the bed (she did, they were brilliant hot-water bottles) and who loved cats more than humans (debatable). It suited them to pigeonhole her, but even real pigeons don’t want to sit in holes. They sit under bridges, perch on ledges, balance on branches. Fly six hundred miles, if they wish, in one single day.

‘What do you reckon?’ Emma said. ‘Might be fun – you can have a poke through people’s lives and find out their deepest, darkest secrets, then tell us all the juicy details!’

Emma cracked up laughing. Nancy paled. Emma had a generous heart at the core of her, Nancy knew that. Like an artichoke.

‘I’m not sure about that,’ Nancy mumbled, but Emma was already designing an advertisement in bubble font.

With the head teacher Mr Phillips’s approval, the advert had gone out in the newsletter and had been pinned up in the staff room, alongside staff notices including the sale of a nearly new paddleboard and a polite reminder about contri. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved