An Alternate History of El Salvador or Perhaps the World

THE SPANISH SHIPS LEAVE THEIR DOCKS, but there is no crash landing, no savior knocking at the isthmus’s shore—only civilization as it was and continues to be. A tempest thrashes La Niña around as men fall off her side in a choir of shrieks and prayers. An empire-size wave swells and crashes down on La Pinta, splintering the cork-oak frame and pine planks. The Santa Maria sinks, full of salty-sweet water, until it sits on the ocean floor. Bottom-feeders nibble on dead Spaniards’ skin.

Another attempt, decades later. This is how the story goes: Thousands of Pipil stand before the Spanish soldiers with spears in their hands, obsidian blades pointed toward the rain clouds as they prepare for a battle that will determine who stays and who leaves this land they know as Cuscatlán or San Salvador; one name Spanish, one name true. The Spanish are on horses, the Pipil on foot, and the air soon fills with the sound of gunfire and screams, the battlefield soaked in gunpowder and horse blood.

The Pipil soldiers find themselves on the precipice of defeat. Enslavement is almost guaranteed. Their skin branded with a red-hot iron, their bodies shipped to a land other than this. They fight, though their cotton-armor is soaked and heavy. Outmanned, losing men by the second, they continue swinging and jabbing. Mud makes their dark skin darker.

Then the clouds shift. The rain intensifies, each droplet expanding into a heavy orb. In the deluge, a Pipil soldier sees an opening and lunges forward. The Spanish army commander’s hair sticks to his forehead as he falls from his horse, pierced in the side by a spear tip. He tumbles into the quagmire, and his blood mixes with brown water. If he doesn’t die there, an infection will inevitably kill him.

The Pipil win the battle, and the Spanish never return. 1524 marks a continuation. The year signifies neither murderous start nor massacred end.

Onward, forevermore. The coast is quiet. Death is just a part of the rainforest’s life cycle, a cosmic part of Earth’s give-and-take. There is no war, no aftermath, no nation. No blood or sweat or singed skin in the dirt.

He Eats His Own

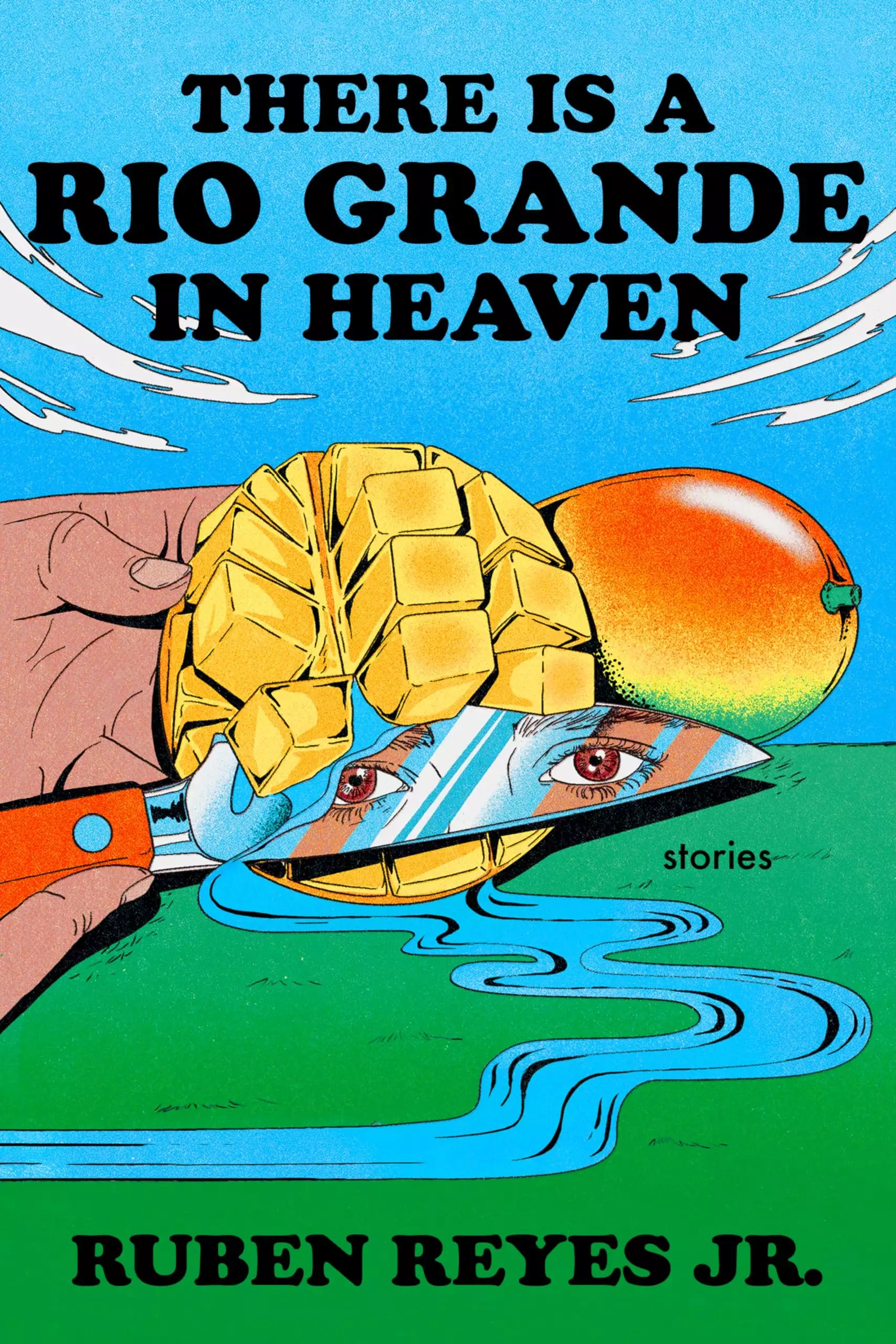

EVERY MORNING, AT 8:05 A.M., Neto pulled out his white plastic cutting board and placed one fresh mango on it. As if conducting an autopsy, he placed the tip of the knife at the top and made a slow, deliberate incision down to the base of the fruit. He repeated the action five times, cutting around the seed until he ended up with six perfect slices. Neto picked each one up by the skin, careful to avoid touching the soft yellow flesh, and dropped it into a bowl he’d pulled from above the counter.

Then he washed the cutting board in the sink, dried it with a freshly pressed dishrag, and put it away, out of sight. Neto’s kitchen was spotless, everything hidden in the cabinets above the marble counter. It was the opposite of the clutter his parents kept at their home when he was growing up, the kind that accumulates when ghosts from the third world prevent you from throwing anything away.

Around 4:30 P.M., Tomas climbed down from Neto’s mango tree slowly, careful not to disturb a single leaf. He’d broken a branch once, sending three mangoes toppling to the ground, and received a beating that left him sore and with a scar that never quite went away. Tomas clutched the day’s harvest close to his chest, secured the padlock on the corrugated metal fence protecting the tree, and ran down the trail leading back to his home.

The brick-wall, dirt-floor home his family lived in had two dining tables. The first was a rectangular table with chipped black paint. This is where they ate dinner. The second was mahogany, covered with a plastic sheet that was easy to disinfect. This was where the mangoes went.

Tomas’s tiny hands held the bag wide open for his mother. Round and round she turned each mango, inspecting every bit of its reddish orange skin. If the mango was imperfect, she’d throw it into the red basket at the foot of the table, her frustration growing with each toss. They needed ten impeccable mangoes. Tomas’s favorites were the mangoes with wormholes because Mami would cut out the ugly bits and let him eat the rest. At high season, he’d sneak fresh ones, even though his parents and cousin forbade it. No one would find the pit in the brush that lined the path to the mango tree.

That afternoon, Tomas brought home a perfect batch; no worms, bruises, or unwanted holes left by hungry birds. Each mango was firm but would be perfectly ripe when they arrived at their destination. Delicately, as if handling diamonds, Mami took each mango and put it in the crate. A cushion padded the bottom, and the sides were lined with felt. She packed the mangoes close together, placing folded rags between them to ensure they wouldn’t shift in transit.

At 10:30 P.M., Papi carried the crate into the passenger seat of his 2001 Toyota Camry, as he did every night. His shoulders, carefully shaped by hours of farmwork, peeked out from his thin white tank top. Tomas watched his muscles flex and relax like the bubbling creek he crossed on the way to Neto’s mango tree. Papi turned on the ignition and made the seventy-five-minute drive from Guazapa to the airport.

Instead of pulling up to the front of the terminals, where family members kissed travelers bearing cardboard boxes full of cheap clothing, Papi went to the back of the airport. In a year and a half of deliveries, he’d never brought a box with a missing or stowaway fruit. A flight attendant counted them anyway, though he profusely apologized. He didn’t doubt that Papi was a trustworthy man, but he had orders to follow.

Papi signed a contract saying he’d delivered the fruit and, shortly after, the ten mangoes were placed onto a wheelchair and pushed into the airport. By the time Papi had returned to his little home in Guazapa, the mangoes were strapped into an economy seat on a five-hour flight to Los Angeles International Airport. Neto always bought

all three seats in a row, so the mangoes could travel undisturbed.

Neto’s boyfriend hated mangoes. It hadn’t always been that way, but after so many mango smoothies, meats served with a mango reduction sauce, and unevenly chopped pieces of mango in his salads, the mere sight of the fruit angered Steven. Once, at the Whole Foods that had replaced a shop specializing in Central American imports, he purposefully knocked over a stack of boxed mangoes. It was all caught on camera and the manager forced him to pay for everything under the threat of arrest, which made Steven despise mangoes even more.

He would never tell Neto how deeply his hatred went. When he admitted he was getting sick of mangoes, Neto had been incredibly understanding, cutting back on the flavor whenever he cooked for them. But still, the fruit’s mere presence bothered Steven, so much so that he changed his work schedule to leave their apartment before Neto got back from the airport. He couldn’t stand the sight of Neto cutting up his breakfast.

Still, he loved Neto for many reasons. Neto was generous with his time and attention, a generosity he extended to Steven and his own parents in equal measure. They’d met a decade earlier, before either of them lived in Los Angeles, at one of those fancy northeastern universities where tuition was higher than the national median income. Neto came from modest money and Steven from nearly none, which meant that they didn’t run in the same circles: different parties, different extracurriculars, different friends. On their fifth date, they realized they’d attended the same Scarface-themed party as sophomores. It was the only social event they remembered being at together. “Impossible to believe I missed a face as handsome as yours in that crowd,” Neto had said.

They reconnected at a crummy alumni reunion put on in Orange County, organized by folks who had graduated at a time when racial slurs were still en vogue and an interracial gay relationship raised major eyebrows. As two of the youngest men there, and by far the handsomest, they slowly drifted to each other. When Neto very vaguely mentioned working in finance, Steven’s interest deflated, but then he made a quip about being as well endowed as the university, and that was enough reason for Steven

feel him out a bit longer. The handsome and rich so seldom needed a personality.

A real attraction emerged from the elitist petri dish of a hotel ballroom and Neto fed it. He made time for dates with Steven, despite working arduous hours and unexpected overtime. He paid for day trips and overnight stays in Joshua Tree and Big Bear. Steven was merely smitten at first, but then fell fully in love with a man who looked at him as if there were nothing more precious in the world. When Neto asked him to move in, Steven didn’t flinch.

They’d been living together for about three months when Neto finally told Steven about his mango tree. Steven laughed at first, but by the end of the night he’d left the apartment, feigning a trip to the gym. Instead, he went to Yogurtland and filled a medium-size cup. Steven surveyed the toppings, calculating whether the kiwi chunks would be lighter than the strawberry slices, and therefore cheaper, until the sight of syrupy, congealed mango bits put him off fruit entirely. He ate plain vanilla in silence, trying to make sense of what Neto had told him.

Neto’s morning drive to LAX was perfect for organizing the loose ends of his life. He called his mother, who was recently on his ass for not keeping in touch.

“It’s been three weeks since I’ve seen you,” she said. Her filtered voice rushed out of the car speakers. She still lived in Neto’s childhood home, on a suburban street full of empty nesters. He visited as often as his work schedule allowed, but it never felt like enough, so he called her almost daily to keep her at bay. The past couple of weeks, though, the strategy was only moderately successful. “Three weeks. I’ve been counting.”

“They’re selling units in a new apartment building in the Arts District, not too far from my place,” Neto said. “It’d be easier to see each other if you didn’t live all the way out in Diamond Bar.”

She tsk-tsked and said it’d be too small. They rehashed the same conversation every couple of months. Neto was willing to buy his parents an apartment, so long as they downsized. The boxes of Christmas decorations, the extra sets of kitchenware, the bags of old hand-me-downs his mother insisted she’d eventually take to his relatives in El Salvador—all of it had to go. Neto told them to leave everything behind, and that he’d furnish the apartment with entirely new things. But his mother hated hearing that, insisting that she needed every piece of her hundred-piece nativity scene. Every box of trinkets was a treasure chest.

“Have you talked to your tia recently?” she asked, changing the subject. The boxes of mangoes arrived fine, so Neto hadn’t.

“Send her a little extra this week,” she said. “She woke up with a massive headache this morning. She won’t ask for it, but she needs money to pay for a doctor’s visit and whatever they might prescribe.”

Neto was pulling up into the airport parking lot, so he promised he would and hung up. When he’d first conceived of the scheme, a deliveryman handled the pickup, but a few weeks in, an aching anxiety set in. Neto spent the earliest hours of his day, which used to be his most productive, worrying. His mangoes were so sweet, so delicious, and he relied on them the way Steven relied on his antidepressants. The delivery took on an almost mythic quality. If he didn’t get his mangoes, everything else he’d built for himself would fall apart too. Until the doorbell rang, Neto was useless, so he began making the drive himself.

Travelers emerged from a hallway below the waiting area. As they climbed up the ramp, pushing carts full of luggage, their loved ones tried desperately to spot them. By now Neto had cataloged the kinds

of hugs exchanged at the airport, hinging on three factors: relationship between the embracers, time gone without having seen each other, and gender of the involved parties. A mother who was reuniting with her son after his two-month summer trip in El Salvador would give a tight embrace, but she wouldn’t cry. She’d be smiling nonstop. A hug from a daughter who hadn’t seen her father for more than a decade—because either the visa or money wasn’t there—would be different. She’d embrace him tightly, like the mother reuniting with her son, but she’d loosen her grip much sooner, realizing that her papi was frailer, wrinklier. Both would cry. Change the daughter into a son, and only the father would let out a few well-controlled tears. Most reunions, though bittersweet, were joyous, brimming with the sort of elation Neto felt seeing Steven after a business trip.

Neto stood alone, waiting, quietly taking in the tears, embraces, laughter, and aroma of Pollo Campero that filled the terminal. When he caught sight of the flight attendant around the corner, pushing a wheelchair with a box of mangoes strapped in, he finally let his guard down. The sight softened his heart, opening it to the other airport-goers’ fervor. Relief and joy rushed him. If he could perform this man-made miracle, again and again, nothing would get in his way.

He handed the flight attendant a ten-dollar tip, hugged the box close to his chest, and made the drive home. By the time he pulled out his cutting board, he’d forgotten about sending the extra money for his aunt.

The night of Neto’s confession, before he had gotten sick of the mangoes, Steven scraped the bottom of his cup with his spoon and laid out what he’d been told.

Neto owned a mango tree in El Salvador. He’d planted it a few years ago, while he was on a trip with his parents. It was on a plot of land that belonged to his uncle. Three summers later, he returned and finally tasted one of the mangoes. They were the best mangoes he’d ever eaten. Neto smuggled a few into the United States, sliced up and hidden in a box of chocolates at the bottom of his luggage. ...

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved