- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

At the end of Worldbinder, Fallion Orden, son of Gaborn, was imprisoned on a strange and fantastic world that he created by combining two alternate realities. It’s a world brimming with dark magic and ruled by a creature of unrelenting evil, one who is gathering monstrous armies from a dozen planets in a bid to conquer the universe.

Only Fallion has the power to mend the worlds, but at the heart of a city that is a vast prison, he lies in shackles. The forces of evil are growing and will soon rage across the heavens. Now, Fallion’s allies must risk everything in an attempt to free him from the wyrmling horde.

Release date: September 9, 2008

Publisher: Tom Doherty Associates

Print pages: 320

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

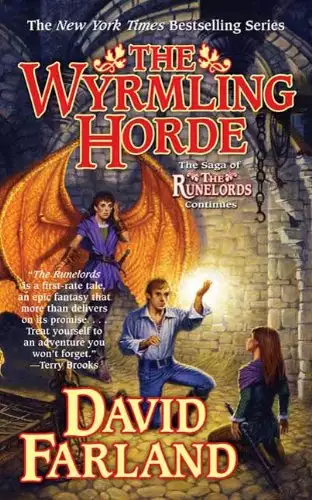

The Wyrmling Horde

David Farland

DANGEROUS NOTIONS

To control a man fully, one must channel his thoughts. You will not have to concern yourself with issues of loyalty once your vassal is incapable of disloyal contemplation.

-The Emperor Zul-torac, on the importance of reinforcing the Wyrmling Catechism on the youth

Cullossax the tormentor strode through the dark warrens of Rugassa, shoving lesser wyrmlings aside. None dared to snarl or raise a hand to stop him. Instead, the pale creatures cowered back in fear. He was imposing in part because of his bulk. At nine feet, Cullossax towered over all but even the largest wyrmlings. The bony plate that ran along his forehead was abnormally thick, and the horny nubs on his head were larger than most. He was broad of chest, and his canines hung well below his lower lip. All of these were signs to other wyrmlings that he was potentially a violent man.

But it was not his brutal appearance alone that won him deference. His black robes of office struck fear in the hearts of others, as did his bloodsoaked hands.

The labyrinth seemed alive with excitement. It coursed through Cullossax's veins, and thrummed through every taut muscle. He could see it in the faces of those that he passed, and hear it in their nervous voices.

Some had fear upon their faces, while others' fears deepened to dread. But some faces shone with wonder or hope, bloodlust or exultation.

It was a rare and heady combination. It was an exciting time to be alive.

Four days ago, a huge army had left Rugassa to destroy the last of the humans at Caer Luciare. The attack was to have begun that very night. Thus the hope upon the people's faces that, after a war that had raged for three thousand years, the last of their enemies would be gone.

But then two days past, everything had changed: a whole world had fallen from the sky, and when it struck, the worlds did not crash and break. Instead, they combined into one whole, a world that was new and different, a world that combined the magics and peoples of two worlds, sometimes in unexpected ways.

Mountains had fallen and rivers had flooded. Ancient forests suddenly sprouted outside the castle gate where none had stood before. There were reports of strange creatures in the land, and all was in chaos.

Now reports were coming from wyrmling outposts in every quarter: there was something new in the land-humans, smaller folk than those of Caer Luciare. If the reports could be believed, they lived by the millions in every direction. It was rumored that it was one of their own wizards who bound the world of the wyrmlings with their own.

Such power was cause enough for the wyrmling's nervousness. But there was also cause for celebration.

Within the past few hours, rumors had been screaming through the chain of command that the Great Wyrm itself had taken a new form and now walked the labyrinth, showing abilities that had never been dreamed, not even in wyrmling legend.

Strange times indeed.

The last battle against the human warrior clans had been fought. Caer Luciare had been taken. The human warriors had been slaughtered and routed.

The news was glorious. But the wyrmlings remained nervous, unsure what might happen next. They stood in small knots and gossiped when they should be working. Some were disobedient and needed to be brought back into line.

So Cullossax the tormentor was busy.

In dark corridors where only glow worms lit his way, he searched through the crèche, where the scent of children mingled with mineral smells of the warren, until at last he found a teaching chamber with three silver stars above the door.

He did not call out at the door, but instead shoved it open. There, a dogmatist stood against a wall with his pupils, wyrmling children fifteen or sixteen years of age. Few of the children had begun to grow the horny nubs at their temples yet, and so they looked small and effeminate.

At the center of the room, a single young girl was chained by the ankle to an iron rung in the floor. She had a desk-a few planks lying upon an iron frame. But instead of sitting at her desk, she crouched beneath it, moaning and peering away distantly, as if lost in some dream. She rocked back and forth as she moaned.

She was a pretty girl, by wyrmling standards. All wyrmlings had skin that was faintly bioluminescent, and children, with their excess energy, glowed strongly, while those who were ancient, with their leathery skin, faded altogether. This girl was a bright one, with silky white hair, innocent eyes, a full round face, and breasts that had already fully blossomed.

"She refuses to sit," said the dogmatist, a stern old man of sixty years. "She refuses to take part in class. When we recite the catechisms, she mouths the words. When we examine the policies, she will not answer questions."

"How long has she been like this?" the tormentor asked.

"For two days now," the dogmatist said. "I have berated her and beaten her, but still she refuses to cooperate."

"Yet she gave you no trouble before?"

"None," the dogmatist admitted.

It was the tormentor's job to dole out punishment, to do it thoroughly and dispassionately. Whether that punishment be public strangulation, or dismemberment, or some other torture, it did not matter.

Surely, this could not go on.

Cullossax knelt beside the girl, studied the child. There had to be a punishment. But Cullossax did not have to dole out the ultimate penalty.

"You must submit," Cullossax said softly, dangerously. "Society has a right to protect itself from the individual. Surely you see the wisdom in this?"

The girl rolled her eyes and peered away, as if carried to some faraway place in her imagination. She scratched at her throat, near a pendant made from a mouse's skull. Cullossax had seen too many like her in the past couple of days, people who chose to turn their faces to the wall and die. Beating her would not force her to submit. Nor would anything else. He would probably have to kill her, and that was a waste. This was a three-star school, the highest level. This girl had potential. So before the torments began, he decided to try reasoning with her.

"What are you thinking?" Cullossax demanded, his voice soft and deep. "Are you remembering something? Are you remembering . . . another place?" That caught the girl. She turned her head slowly, peered into Cullossax's eyes. "Yes," she whimpered, giving out a soft sob, then she began shaking in fear. "What do you remember?" Cullossax demanded.

"My life before," the child said. "I remember walking under green fields in the starlight. I lived with my mother there, and two sisters, and we raised pigs and kept a garden. The place we lived in was called Inkarra."

Just like so many others. This was the third today to name that place.

Each of them had spoken of it the same, as if it were a place of longing. Each of them hated their life in Rugassa.

It was the binding, of course. Cullossax was only beginning to understand, but much had changed when the two worlds were bound into one.

Children like this girl claimed to recall another life on that other world, a world where children were not kept in cages, a world where harsh masters did not make demands of them. They all dreamed of returning.

"It is all a dream," Cullossax said, hoping to convince her. "It isn't real. There is no place where children play free of fear. There is only here and now. You must learn to be responsible, to give away your own selfish desires.

"If you continue to resist," Cullossax threatened, "you know what I must do. When you reject society, you remove yourself from it. This cannot be tolerated, for then you are destined to become a drain upon society, not a contributor.

"Society has the right, and the duty, to protect itself from the individual." Normally, at this time, Cullossax would afflict the subject. Sometimes the very threat of torment would strike enough fear into the heart of the reprobate that she would do anything to prove her obedience. But Cullossax had discovered over the past two days that these children were not likely to submit at all.

"What shall I do with you?" Cullossax asked.

The girl was shaking still, speechless with terror.

"Who is society?" she asked suddenly, as if she had come upon a plan to win some leniency.

"Society consists of all of the individuals that make up the whole," Cullossax said, quoting from the catechisms that the child was to be studying.

"But which one of the people makes up the rules?" she asked. "Which one of them says that I must die if I do not follow the rules?"

"All of them," Cullossax answered reasonably. But he knew that that was not true.

The girl caught him in his lie. "The catechisms say that 'Right acts follow from right thinking.' 'But youth and stupidity are barriers to right thinking. Thus, we must submit to those who are wiser than we.' 'Ultimately the emperor, by virtue of the great immortal wyrm that lives within him, is wisest of all.' "

Wyrmling education consisted of rote memorization of the catechisms, not upon learning the skills of reading and writing. The wyrmlings had found that forcing children to memorize the words verbatim trained their minds well, and in time led to an almost infallible memory. This girl had strung together some catechisms in order to form the core of an argument. Now she asked her question: "So if the emperor is wisest, does not the emperor make the rules, rather than the collective group?"

"Some might say so," Cullossax admitted.

"The catechisms say, 'Men exist to serve the empire,' " the girl said. "But it seems to me that the emperor's teachings lead us to serve only him."

Cullossax knew blasphemy when he heard it. He answered in catechisms:

" 'Each serves society to the best of his ability, the emperor as well as the least serf,' " Cullossax reasoned. " 'By serving the emperor, we serve the great wyrm that resides within him,' and if we are worthy, we shall be rewarded. 'Live worthily, and a wyrm may someday enter you, granting you a portion of its immortality.' "

The child seemed to think for a long time.

Cullossax could not bother with her any longer. This was a busy time. There had been a great battle to the south, and the troops would begin to arrive any day. Once all of the reports had been made, Cullossax would be assigned to deal with those who had not distinguished themselves in battle. He would need to sharpen many of his skinning knives, so that he could remove portions of flesh from those who were not valiant. With the flesh, he would braid whips, and then lash the backs of those that he had skinned.

And then there were people like this girl-people who had somehow gained memories of another life, and who now sought to escape the horde. The tormentors had to make examples of them.

Cullossax reached under his collar, pulled out a talisman that showed his badge of office: a bloody red fist. The law required him to display it before administering torture. "What do you think your torment should be?" Cullossax asked.

Trembling almost beyond control, the girl turned her head slowly, peered up at Cullossax. "Doesn't a person have the right to protect himself from society?"

It was a question that Cullossax had never considered. It was a childish question, undeserving of consideration. "No," he answered.

Cullossax would normally have administered a beating then, perhaps broken a few bones. But he suspected that it would do no good. "If I hurt you enough, will you listen to your dogmatist? Will you internalize his teachings?"

The girl looked down, the wyrmling gesture for no.

"Then you leave me no choice," the tormentor said.

He should have strangled the child then. He should have done it in front of the others, so that they could see firsthand the penalty for disobedience.

But somehow he wanted to spare the girl that indignity. "Come with me," he said. "Your flesh will become food for your fellows."

Cullossax reached down, unlocked the manacle at the girl's foot, and pulled her free from the iron rung in the floor. The girl did not fight.

She did not pull away or strike back. She did not try to run. Instead, she gathered up her courage and followed, as Cullossax held firmly to her wrist.

I would rather die than live here, her actions seemed to say.

Cullossax was willing to oblige.

He escorted the girl from the room. Her fellows jeered as she left, heaping abuse upon her, as was proper.

And once the two were free of the classroom, the girl walked with a lighter step, as if glad that she would meet her demise.

"Where are we going?" the child asked.

Cullossax did not know the girl's name, did not want to know her name.

"To the harvesters." In wyrmling society, the weak, the sickly, and the mentally deficient were often put to use this way. Certain glands would be harvested-the adrenals, the pineal, and others-to make extracts that were used in battle. Then the bodies were harvested for meat, bone, skin, and hair. Nothing went to waste. True, Rugassa's hunters roved far and wide to supply the horde with food, but their efforts were never enough.

"Will it hurt?"

"I think," Cullossax said honestly, "that death is never kind. Still, I will show you what leniency I can."

It was not easy to make such promises. As a tormentor, Cullossax was required to dole out the punishments required by law without regard to compassion or compromise.

That seemed to answer all of her questions, and Cullossax led the girl now effortlessly down the winding corridors, through labyrinthine passages lit only by glow worms. Few of the passages were marked, but Cullossax had memorized the twists and turns long ago. Along the way, they passed through crowded corridors in the merchant district where vendors hawked trinkets carved from bones and vestments sewn from wyrmling leather. And near the arena, which was empty at the moment, they passed through lonely tunnels where the only sound was their footsteps echoing from the stone walls. Fire crickets leapt up near their feet, emitting red flashes of light, like living sparks. Once, he spotted a young boy with a bag of pale glow worms, affixing one to each wall, to keep the labyrinth lighted.

Cullossax wondered at his own reasons for wanting to show her compassion. It was high summer, and in a few weeks he would go into musth. Already he felt the edginess, the arousal, and the beginnings of the mad rage that assailed him at this time of year. The girl was desirable enough, though she was too young to go into heat.

The girl's face was blank as she walked toward her execution. Cullossax had seen that look so often before.

"What are you thinking about?" he asked, knowing that it was easier if he kept them talking.

"There are so many worlds," she said, her voice filled with wonder. "Two worlds have combined, and when they did, two of my shadow selves became one. It's like having lived two lifetimes." She fell silent for a second, then asked, "Have you ever seen the stars?" Most wyrmlings in the labyrinth would never have been topside.

"Yes," he answered, "once."

"My grandmother was the village wise woman at my home in Inkarra," the girl said. "She told me that every star is but a shadow of the One True Star, and each of them has a shadow world that spins around it, and that there are a million million shadow worlds."

"Hah," Cullossax said, intrigued. He had never heard of such a thing. The very strangeness of such a cosmology drew his interest.

"So think," the girl said. "Two worlds combined, and when they did, it is like two pieces of me came together, making a larger whole. I feel stronger than ever before, more alive and complete. Here in the wyrmling horde, I was driven and cunning. But on the other world, I was learning to be wise, to take joy in life." She gave him a moment to think, then asked, "What if there are other pieces of me out there? What if I have a million million shadow selves, and all of them combined into one person in a single breath? What would I be like? What things would I know? It would be like having lived a billion lifetimes all at once. Perhaps on a few thousand worlds, I might have learned perfect self-discipline, and on others I might have spent lifetimes studying how to make peace among warring nations. And if I were combined into one, imagine how whole all of those shadow selves would become."

The thought was staggering. Cullossax could not imagine such a thing.

"They say a wizard combined the worlds," Cullossax said. "They say he is in the dungeon now."

And I wish that I had the honor of being his tormentor, Cullossax thought.

"Perhaps we should be helping him," the girl suggested. "He has the power to bind all of the worlds into one."

What good would that do me? Cullossax wondered. Perhaps I have no other selves on other worlds.

He was lost in thought when she struck. It happened so fast, she almost killed him. One instant she was walking blithely along, and the next moment she pulled a dagger from her sleeve and lunged-aiming for his eye.

But his great height worked against her. Cullossax dodged backward, and the dagger nicked him below the eye. Blood sprang from the wound, as if he cried tears of blood. Fast as a mantis taking a cave cricket, she struck again, this time aiming for his throat. He raised an arm to block her swing. She twisted to the side and brought the dagger up to his kidney. It was a maneuver he'd learned as a youth, and he was ready for her. He reached down and caught her arm, then slammed her into a wall.

The vicious creature screamed and leapt at him, her thumbs aimed at his eyes. He brought up a knee that caught her in the rib cage, knocking the air out of her.

Even injured she growled and tried to fight. But now he had her by the scruff of the neck. He pinned her to the wall and strangled her into submission.

It was a good fight from such a small girl-well timed and ruthless. She was not just a victim waiting to go to her death. She'd planned this all along!

She'd lured him into the corridor, waited until they were in a lonely stretch of the warrens, and then done her best to leave him lying in a pool of blood.

Doubtless, she had some plan for escape.

Cullossax laughed. He admired her feistiness. When she was barely conscious, he reached into her tunic and felt for more weapons. All he felt was her soft flesh, but a thorough search turned up a second dagger in her boot.

He threw them down the corridor, and as the girl began to come to, he put her in a painful wristlock and walked her to her death, whimpering and pleading.

"I hate you," she cried, weeping bitter tears. "I hate the world you've created. I'm going to destroy it, and build a better one in its place."

It was such a grandiose notion-one little wyrmling girl planning to change the world-that he had to laugh. "It is not I who made this world."

"You support it," she accused. "You're as guilty as the rest!"

It happened that way sometimes. Those who were about to die would search for someone to accuse, rather than take responsibility for their own stupidity or weakness.

But it was not Cullossax who had created her world. It was the Great Wyrm, whom some said had finally taken a new form, and now walked the halls of Rugassa.

As they descended some stairs, a fellow tormentor who was climbing up from below called Cullossax to a halt. "Have you heard the news?"

"What news?" Cullossax asked. He did not know the man well, but tormentors all belonged to a Shadow Order, a secret fraternity, and had sworn bloody oaths to protect one another and uphold one another and to promote one another's interests, even in murder. Thus, as a tormentor, this man was a brother to him.

"Despair has taken a new body, and now walks the labyrinth, displaying miraculous powers. As one of his first acts, he has devised a new form of torture, surpassing our .nest arts. You should see!"

Cullossax stood for a moment, overwhelmed. The Great Wyrm walked among them? He still could not believe it. Obviously, with the binding of the worlds, Despair felt the need to con.rm his supremacy.

The very thought filled Cullossax with awe. This was a great time to be alive. "So," Cullossax teased, "Despair wants our jobs?"

The tormentor laughed at the jest, then seemed to get an idea. "You are taking the girl to be slaughtered?"

"Yes," Cullossax said.

"Take her to the dungeons instead, to the Black Cell. There you will find Vulgnash, the Knight Eternal. He has had a long fight and needs to feed. The girl's life should be sweet to him."

The girl suddenly tried to rip free, for being consumed by a Knight Eternal was a fate worse than death.

Cullossax grabbed the girl's wrist, holding her tight. She bit him and clawed at him, but he paid her no mind.

Cullossax hesitated. A Knight Eternal had no life of his own. Monsters like him did not need to breathe or eat or drink. Vulgnash could not gain nourishment by digesting flesh. Instead, he drew life from others, consuming their spiritual essence-their hopes and longings.

Cullossax had provided the Knight Eternal with children before. Watching the monster feed was like watching an adder consume a rat.

In his mind's eye, Cullossax remembered a feeding from five years ago.

Then Vulgnash, draped in his crimson robes, had taken a young boy.

Like this girl, the boy had screamed in terror and struggled with renewed fury as they neared Vulgnash's lair.

"Ah," Vulgnash had whispered, his wings quivering slightly in anticipation, "just in time."

Then Vulgnash had turned and totally focused on his victim. He seemed unaware that Cullossax was watching.

The boy had cried and backed away into a corner, and every muscle of Vulgnash's body was taut, charged with power, lest the child try to run.

The boy did bolt, but Vulgnash lashed out and caught him, shoved him into the corner, and touched the child on the forehead-Vulgnash's middle finger resting between the child's eyes, his thumb and pinky on the boy's mandibles, and a finger in each eye. Normally when a child was so touched, he ceased to fight. Like a mouse that is filled with scorpion's venom, he would go limp.

But this boy fought. The child grabbed Vulgnash's wrist and tried to shove him away. Vulgnash seized the boy by the throat with his left hand then, and maintained his grip with the right. The child bit at the Knight Eternal's wrist, fighting valiantly.

"Ah, a worthy one!" Vulgnash enthused.

The boy tried twisting away. He began to scream, almost breaking Vulgnash's grasp. There was a world of panic in the child's eyes.

"Why?" the child screamed. "Why does it have to be this way?" "Because I hunger," Vulgnash had said, shoving the boy into the corner, holding him fast. As the boy's essence began to drain, he shrieked in panic and shook his head, trying to break free of the monster's touch. All hope and light drained from his face, and was replaced by an endless well of despair. His cries of terror changed into a throaty wail. He kicked and fought for a long moment while Vulgnash merely held him up against the wall.

The Knight Eternal leaned close, his mouth inches from the boy's, and then began to inhale, making a hissing sound.

Cullossax had seen a thin light, like a mist, draining away from the child into Vulgnash's mouth.

Slowly, the child quit struggling, until at last his legs stopped kicking altogether. When the Knight Eternal was done, he'd dropped the child's limp body.

The boy lay in a heap, staring up into some private horror worse than any nightmare, barely breathing.

"Ah, that was refreshing," Vulgnash said. "Few souls are so strong." Cullossax had stood for a moment, unsure what to do. Vulgnash jutted a chin toward the boy. "Get rid of the carcass."

Cullossax then grabbed the limp form and began dragging it up the corridor. The boy still breathed, and he moaned a bit, as if in terror.

Grabbing the child's head, Cullossax had given it a quick twist up and to the right, ending the child's life, and his torment.

Thus, Cullossax knew how this feeding would turn out. The Knight Eternal would put a hand over this girl's pretty face, lean in close, almost as if to kiss, and with one indrawn hiss he would drain the life from her. He would take all of her hope and aspiration, all of her enjoyment and serenity.

Realizing her fate, the girl fought to break free. She jerked her hand again and again, trying to break Cullossax's grasp, but Cullossax seized the child's wrist, digging the joint of his thumb into the ganglia of the girl's wrist until her knees gave out from the pain.

He wanted to see this new form of torture, so he dragged her to the dungeon. "Please," she cried. "Take me back to the crèche. I'll listen to the dogmatist! I'll do anything. I promise!"

But it was too late. The girl had chosen her fate. She let her knees buckle, refusing to walk any farther. Cullossax dragged the girl now, his fingernails biting into her flesh as she whimpered and pleaded and tried to grab the legs of passersby.

"We don't have to live like this!" the girl said. "Inkarra does exist!" That gave Cullossax pause. Could it be that there was a land without the Death Lords, without the empire? Could it be that people there lived pleasant lives without care?

For one person to tell of it was madness. For two to tell of it was a fluke. But this girl was the third in a single day. A pattern had emerged.

And then there was the matter of the small folk. Since the change, Cullossax had heard rumors that there might be millions of them in the world.

"Who is the emperor in this land of yours?" Cullossax asked.

"I did not serve an emperor there," she said. "But there was a great king, the Earth King, Gaborn Val Orden, who ruled with kindness and compassion. He told me when I was a child that 'the time will come when the small folk of the world must stand against the large.' He said that I would know when that time had come. Gaborn Val Orden served and protected his people. But our emperor only feeds on his people!"

The name Orden was known to Cullossax. It was a strange name, hard on the wyrmling tongue. As a tormentor, Cullossax was privy to many secrets. Just after dawn a prisoner had been delivered to the dungeon, a powerful wizard named Fallion Orden-a wizard who had been the son of a great king on another world, a wizard who had such vast powers that he had bound two worlds into one.

Now the great Vulgnash himself had been assigned to guard this dangerous wizard. "Where is this realm of Inkarra?" Cullossax demanded.

"South," the child said. "Their warrens are to the south, beyond the mountains. Let me go, and I can show you. I'll take you there."

It was a curious offer. But Cullossax had a job to do.

Down he led the child, past the guards who blocked his way, into the dungeons where light never reached.

The girl struggled, twisting and scratching at his hand, until he cuffed her hard enough so that she went limp, and her struggles ceased.

Her mouth fell open, revealing her oversized canines. Small rubies had been inset into each of them, rubies carved to look like serpents. It was a symbol of her status, as one of the intellectual elite.

How far you have fallen, little one, Cullossax thought.

At the outer gates to the dungeons, he took the necklace from around his neck and used the key to enter.

At last he reached the Black Cell, the most heavily guarded of all.

Cullossax drew near its iron door, and would have opened it, but a pair of guards blocked him. Cullossax could see through a grate in the door. Inside, a bright light shone. Vulgnash stood in his red cowl and robes, his artificial red wings flapping slightly. He loomed above a small human, a man with dark black hair, and a pair of wings. The ground in the cell was rimed with frost, and Cullossax's breath came out as a fog when he peered in.

Within the cell stood a wyrmling lord, a captain dressed in black, a man with the papery hands of one who had almost given up the flesh, one who was almost ready to transition to Death Lord. He was holding up a thumblantern, examining the wizard Fallion Orden.

There was no sign of this wondrous new torture that the tormentor had told Cullossax about. Cullossax had expected to see some novel contraption—perhaps an advancement upon the crystal cage, the tormentor's most sophisticated device.

Now the Death Lord spoke softly, his voice almost a hiss.

Cullossax was not supposed to hear, he suspected, but wyrmlings have sharp ears, and his were sharper than most.

"We must take care," the Death Lord whispered. "Despair senses a coming danger. It is dim, but it haunts us nonetheless. He told me to bring warning."

"A danger to whom?" Vulgnash asked.

"To our fortress guards," the captain said. "He suspects that humans are

coming, a force small but powerful. They are coming here, to this cell. They hope to free Fallion Orden."

"Then I will be ready for them," Vulgnash said.

"We must be ready," the captain said. "The humans will send their greatest heroes. We must be sure that they are properly received. We have sent

for forcibles. When they come, you will need further endowments."

The Death Lord peered hard at Vulgnash. "You look weak. Do you need

a soul to feed upon?"

"I have sent for one."

The Death Lord laughed softly, a mocking laugh, as if at some private joke. He was laughing at Vulgnash's victim.

Cullossax stepped back from the iron door, peered

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...