SARAJEVO, 1914

THE HOLY ONE kept creating worlds and destroying them, creating worlds and destroying them, and then, just before giving up, He finally came up with this one. And it could be much worse, this world and all that it holds, as I certainly know how to get my hands on some interesting stuff around here. Let’s see: lapis infernalis, laudanum, next to it, lavender.

—vast Mediterranean flower fields stretched inside him, the blue sea lapping at his soul, a turquoise sky and swallows floating above it all, the laudanum sailing on his blood all the way to his mind, and then beyond. To all the things created at twilight on the Šabat eve, the Lord wisely added laudanum, just to help make everything more beautiful and bearable.

Now was Rafael Pinto much better prepared for the Archduke Franz Ferdinand von Österreich-Este, Heir Apparent to the Habsburg Empire and Inspector General of the Imperial Armed Forces, and for the whole spectacle he was bringing to Sarajevo just to see how we live here. We live rather well, Your Highness, I must say, provided there is enough laudanum and lavender on hand, thank You very much for Your kind concern. And since this is an enterprise of providing remedy for the body as much as for the soul, we’re sure to have plenty of whatever we might need, long live the Emperor, the Lord be praised, and bless You too.

After a drab, rainy week, the morning was sunny and the light broke through the windows as never before, rearranging the checkered floor into unprecedented patterns. The sugar was now completely dissolved but the bitterness lingered, tickling his tongue. God wrapped Himself in white garments, and the radiance of His majesty illuminated the world, and right here on the floor of the Apotheke Pinto we can now behold a little patch of one of those very garments. There might be a poem for me to write about the light shifting and altering the visible: God’s Garments, it could be called. But then, who would ever care about any of it, no one cares about light and what it does to the soul, not here in this city behind God’s back.

Ever since Vienna, Pinto had been writing poetry in German; he wrote in Bosnian too, but only about Sarajevo. He even tried to write in Spanjol, but that always felt like his Nono was writing it, everything always sounding like an ancient proverb: Bonita de mijel, koransiko de fijel; Kazati i veras al anijo mi lo diras, and so on. Whereas light is everywhere and nowhere. It exists, but never by itself, always a garment, just as God is knowable only in the imperfection of His Creation. Even darkness is clothed in light; light makes itself present by its own absence. We carry the darkness inside and return it to the light when we die. That could sound good in German. Im Inneren tragen wir das Licht, da wir, wann wir sterben, zurückgeben der Finsternis.

He put the laudanum and lavender up on the shelf. The opiatic ease set in, slowly, like a deep breath, while he studied the floor smeared with shadows from letters in the window. apotheke pinto. He should finally get rid of all the silly herbs Padri Avram had bought from peasants and collected for decades. Padri had insisted that all that junk be moved from the old drogerija in the Čaršija and put up alongside the actual medicine, which he had derisively called the patranjas. But, moved though they may have been, all those obscure, old-fashioned herbs were now dry and dead, their ancient, cumbersome Turkish names (amber kabugi;

SARAJEVO, 1914

THE HOLY ONE kept creating worlds and destroying them, creating worlds and destroying them, and then, just before giving up, He finally came up with this one. And it could be much worse, this world and all that it holds, as I certainly know how to get my hands on some interesting stuff around here. Let’s see: lapis infernalis, laudanum, next to it, lavender.

Pinto took the laudanum off the shelf, knocking over the lavender tin, which miraculously did not break open when it hit the floor. He released a drop of laudanum onto a sugar lump, watched the brown stain bloom, then placed it in his mouth. While the sugar and bitterness dissolved on his tongue, he picked up the lavender, dipped his nose into the tin, and inhaled—vast Mediterranean flower fields stretched inside him, the blue sea lapping at his soul, a turquoise sky and swallows floating above it all, the laudanum sailing on his blood all the way to his mind, and then beyond. To all the things created at twilight on the Šabat eve, the Lord wisely added laudanum, just to help make everything more beautiful and bearable.

Now was Rafael Pinto much better prepared for the Archduke Franz Ferdinand von Österreich-Este, Heir Apparent to the Habsburg Empire and Inspector General of the Imperial Armed Forces, and for the whole spectacle he was bringing to Sarajevo just to see how we live here. We live rather well, Your Highness, I must say, provided there is enough laudanum and lavender on hand, thank You very much for Your kind concern. And since this is an enterprise of providing remedy for the body as much as for the soul, we’re sure to have plenty of whatever we might need, long live the Emperor, the Lord be praised, and bless You too.

After a drab, rainy week, the morning was sunny and the light broke through the windows as never before, rearranging the checkered floor into unprecedented patterns. The sugar was now completely dissolved but the bitterness lingered, tickling his tongue. God wrapped Himself in white garments, and the radiance of His majesty illuminated the world, and right here on the floor of the Apotheke Pinto we can now behold a little patch of one of those very garments. There might be a poem for me to write about the light shifting and altering the visible: God’s Garments, it could be called. But then, who would ever care about any of it, no one cares about light and what it does to the soul, not here in this city behind God’s back.

Ever since Vienna, Pinto had been writing poetry in German; he wrote in Bosnian too, but only about Sarajevo. He even tried to write in Spanjol, but that always felt like his Nono was writing it, everything always sounding like an ancient proverb: Bonita de mijel, koransiko de fijel; Kazati i veras al anijo mi lo diras, and so on. Whereas light is everywhere and nowhere. It exists, but never by itself, always a garment, just as God is knowable only in the imperfection of His Creation. Even darkness is clothed in light; light makes itself present by its own absence. We carry the darkness inside and return it to the light when we die. That could sound good in German. Im Inneren tragen wir das Licht, da wir, wann wir sterben, zurückgeben der Finsternis.

He put the laudanum and lavender up on the shelf. The opiatic ease set in, slowly, like a deep breath, while he studied the floor smeared with shadows from letters in the window. apotheke pinto. He should finally get rid of all the silly herbs Padri Avram had bought from peasants and collected for decades. Padri had insisted that all that junk be moved from the old drogerija in the Čaršija and put up alongside the actual medicine, which he had derisively called the patranjas. But, moved though they may have been, all those obscure, old-fashioned herbs were now dry and dead, their ancient, cumbersome Turkish names (amber kabugi; bejturan; logla-ruhi) sticking out in the neat alphabetical order of the patranjas, which Pinto had established after the move. He didn’t even know what they were for, those magic herbs. In the old place, only Padri knew where to find things and what the principles of classification were—the drogerija had really represented the interiority of Padri’s head, all the books and the prikantes and segulot and basme on the shelves, and the burnt-sugar scent of the halva he had with coffee, crawling against the ceiling, the clouds of tobacco smoke as dense as his thoughts. Those ancient peasants of his still came by the Apotheke sometimes, clad in their sheep-stink clothes and animal-hide footwear, with their random ripe boils marring their mountain veneer, with their untold diseases, gnarled bones, and rotten teeth. They’d enter and look around as if they’d just disembarked from a ramshackle time machine, disoriented by the camphor smell and the serene medicinal quiet and the marble floor, awed by Emperor Franz Joseph’s baroque backenbart in the picture they could not fail to see. Only Nono Solomon’s picture on the opposite wall, dating from the last century, assured them they actually were where they were meant to be: they recognized Nono’s fez, his furrowed brow and stately white beard, even his kaftan adorned with a medal on his chest, pinned once upon a time by none other than a representative of the Sultan Abdul Hamid himself. The peasants would ask for the old Jewish hećim, and Pinto would have to tell them that the old hećim was dead and gone, and that he—Doktor Rafo to them—was now the rightful heir of this medicinal little empire and that the only herb he would ever be interested in buying from them was lavender. But there was little lavender in the grim mountains around Sarajevo, so the peasants returned unrewarded to their thick and ancient forests, where they lived and copulated with wild beasts, and never came back to the Apotheke Pinto, which was just as well. Because we now lived in a brand-new century, progress was everywhere to behold, the future was endless, like a sea—nobody could see the end of it. No one cared about bejturan anymore. Amber kabugi was probably something that summoned ghosts or killed witches and vilas, made your teeth fall out, caused a never-ending erection. Well, that wouldn’t be half as bad.

The morning had started with a cannon salvo, welcoming to our beloved Godforsaken city the Archduke Franz Ferdinand von Österreich-Este, Heir Apparent to the Habsburg Empire and Inspector General of the Imperial Armed Forces, accompanied by Her Highness the Duchess. Now there was another boom, an extra welcome to His and Her Highness. (Only later that day would Pinto find out that the boom had been caused by a hand grenade a hapless young assassin had hurled at the Archduke’s car. I can confirm, from personal experience, that we are always late to the history in which we live.) Across the street, Hadži-Besim had hung the imperial banner above his tobacco shop as per Governor’s order, and presently stood under it, his thumbs stuck in the vest pockets, the top of his claret fez nearly touching the black-and-yellow rag with the stiff Austrian eagle in the center. But the colors were pleasingly aligned, and the smooth rotundity of Hadži-Besim’s stomach was just as pleasant. Laudanum helps the world be snug inside God’s garments. Pinto realized he should’ve put the banner above the door as well; he was planning to, never got around to it; there were so many banners all over the city, nobody would notice the absence of his. Nono Solomon and the Emperor frowned at him from their opposite walls, rebuking him with their aged and stolid wisdom for his negligence, and for many other things as well; they watched him all the time, the mighty old men. This was a century of progress; great things were coming our way. Remember the future! The Archduke Franz Ferdinand von Österreich-Este, Heir Apparent to the Habsburg Empire, himself came to Sarajevo to see how we live, and tell us how we can live even better.

And there he was now, the Archduke, like a prince straight out of a fairy tale, banging on the pharmacy’s door, more specifically on the A in apotheke pinto, ignoring the sign that said it was closed. Behold the famous steel-blue eyes and the upturned hussar’s mustache now pressed against the glass as He peers inside! What would His Highness want from Pinto’s humble self? What could one Rafael Pinto ever offer to the Heir Apparent, other than his unlimited and undying loyalty, his joy at casting his gaze on His Imperial countenance? He hurried over to unlock the door, slowing down and stepping around—just in case—the recondite reticulation of the light and the shadow. Light changes the world, yet it stays the same, ever warm inside God’s garments. Das Licht ändert die Welt und jedoch bleibt sie gleich, auf ewig warm unter Gottes Gewänder.

The Archduke was not the Archduke at all, though he certainly entered like one, as if everything before him belonged to him, importing venerable mothball residues in his ceremonial Rittmeister uniform, a sash across the chest like a perfectly made bed, the meticulously shaven and powdered face, and the wax in the symmetrically pointed mustache, and his splendorous helmet with a perfumed horsehair hackle, and a tinge of sweat underneath it all—he smelled, all of him, like the Vienna Pinto had known so well, like the very first day of the century of progress, he smelled like something that accelerated Pinto’s heartbeat and made his palms sweat. He rubbed them against his sides.

The Rittmeister’s saber cackled against the stairs as he stepped down. He took off his helmet to execute a perfect about-face. A decision behind his own thought, Pinto still held the door open. The heat and the din of a distraught pigeon flock, of an anxious crowd, rushed inside. Bitte! said Pinto, and closed the door, locked it too. Bleib mein schlagendes Herz.

The heat was unbearable, the Rittmeister said, dabbing his forehead with a whitest handkerchief, just horrid and unbearable, and he desperately needed some kind of powder for his insufferable headache. And he also wondered why there was no Royal banner above the entrance. He spoke to Pinto with a curt Viennese accent; there was the shadow of an A on his sashed belly; stars glittered on his uniform’s collar. His eyes had a melancholy, consumptive sheen, so Pinto was compelled to consider his widening pupils, until the Rittmeister averted his gaze, a breath too late. His lips were cracked and he licked the upper one. The tip of his tongue touched his mustache.

As for the banner, Pinto said, bowing, he humbly begged for forgiveness—too much excitement in expectation of this glorious day evidently got in the way. He would be glad to rectify his error promptly, but before that, with Herr Rittmeister’s kind permission, he should rather hasten to fetch the powder that would almost certainly alleviate Herr Rittmeister’s headache. The Rittmeister clicked his heels and nodded in appreciation. Erect he stood in the center of the light field, as if accustomed to being admired.

It all rushes back to Pinto, that joyous time in Vienna when his jetzer hara reigned: the glances exchanged on the promenade along the Danube, in the crowded student cafés; the tinglingly surreptitious touches in the hoi polloi theaters; the poetry quotes encoded with desire, flaring out in the middle of a carefully innocuous conversation; the mischievous emergence of the very same dimples on the face of one Hauptmann Freund as he offered his passionate and false opinions on women, on Sacher torte, on Schubert, on love, on laudanum, on Oberst Redl, even—daringly—on Herr Pinto’s exotic facial features expressing capacity for passion, until Rafael shut him up with a kiss. Gute Nacht und Guten Morgen, Hauptmann Freund!

Oh, we could live so much better!

Behind the counter Pinto crushes with his trembling hands the ingredients into the powder, recalling a future moment—the moment he’ll be caressing, as if inadvertently, the Rittmeister’s hand, thereby transmitting the currents of his passion. The Rittmeister has repositioned himself to stand before Nono Solomon’s photograph, his chin upturned in wonder as though he had never seen a Sefaradi, which he probably hadn’t. He would not be able to connect Pinto—fezless in his suit and cravat, a gold chain across his stomach, and, despite his swarthy face, European as can be—with the sepia sheen of the Ottoman past and Nono’s biblical frown. Who created Heaven and Earth, who installed this thunderous heart inside my chest?

Pinto envisions grabbing the Rittmeister’s hand and then pulling him deeper into the back room to grab his hanino face and kiss him, the full submission to the impulse: sliding the sash aside, the manly chest, the infernal depths of the body, touching his already stiff pata, the heart bursting with pleasure. They would be safe—no one is going to come in, the pharmacy is closed, the door is locked, it is Sunday, and the whole world is busy with kowtowing to the Archduke Franz Ferdinand von Österreich-Este, Heir Apparent to the Habsburg Empire and Inspector General of the Imperial Armed Forces. Who would care to see der Kuss in the dark back room of the Apotheke? Even the Holy One, who is everywhere and nowhere, might wish to look away when I press my lips against his. What is in your heart about your fellow man is likely to be in his heart about you. Šalom, jetzer hara!

Pinto finishes the powder, pours it onto a paper sheet, spilling it all over, then collecting into a heap to scoop it with the paper edge, folds it slowly, as if presenting a way to perform a magic trick. He hands the triangular envelope to the Rittmeister, who may have noticed the tremor in Pinto’s hand. Their fingers touch, their eyes meet.

Naturally, nothing happens.

May I ask you for a glass of water? the Rittmeister says.

Rosenwasser? Pinto offers.

The Rittmeister pours the powder into his mouth; his Adam’s apple bobs as he downs the rose water. A faint nick on the tip of his chin; his mustache is perfect. He looks toward the ceiling as he downs the rose water, empties the whole glass, and then sighs with what seems to be pleasure. There could be a future in which the Rittmeister faces a mirror, gorgeous in his undershirt and his tight rider’s pants, the suspenders hanging down his thighs to his knees. Pinto conjures up the morning in a Viennese room—the shaving soap and cigarette smoke, and a rose in a glass at the bedside, still fresh from last night; crumpled bedsheets; on the wall, a painting of a path winding into a dark forest. His name is Kaspar, Pinto determines. Kaspar von Kurtzenberger. Guten Morgen, Kaspar! he will say. Guten Morgen, Rafael! Kaspar will say. Did you sleep well? Not at all, mein Lieber. I spent the night listening to your beating heart.

Dankeschön! says Kaspar. He returns the empty glass to Pinto, and then dabs his lips with the pristine handkerchief.

Bitte! whispers Rafael, his throat dry and tight.

Before Pinto can unlock and open the door, the Rittmeister stops, his gloved hand on the pommel of his saber, to consider Rafael as if he had one more thing to say. He says nothing, his gaze long and deep, waiting for something to happen or reveal itself. Now is the time to step up and kiss him farewell. Their eyes lock; his eyes are in fact green. The Rittmeister smiles, without exposing his teeth, dimples forming above the very peaks of his waxed mustache.

Before he could make any decision, Pinto rises on the tips of his toes, and kisses the Rittmeister right at the border between his mustache and his lip. It tastes of rose water and tobacco, of wax and sugar. The Rittmeister moves his face away from Pinto’s, not to escape him but to look at him with bemused surprise. He glances outside to see if anyone has seen what happened, but everyone outside is looking in the direction from which the Archduke is supposed to come; the only sound is distant cheers. Jetzer hara has taken over, and Pinto has no thoughts that are not dizeu; his pata hardens. He still has the glass in his hand, he is still aware of the world beyond the Apotheke, but all of it is distant and receding. Pinto kisses the Rittmeister again, and this time Kaspar opens his mouth, and Pinto takes in his rose breath. This is crazy; he’s never done anything like this, and he knows how dangerous it is, and yet he can’t stop. The man’s lips are soft; the kiss is quick but gentle, and in the time it takes, in the muscled hardness of the Rittmeister’s chest, there is an entire possible life.

Kaspar, Pinto says, and presses his cheek against the Rittmeister’s chest. Kaspar.

It is only then the Rittmeister steps back, as if what happened did not happen, and asks, Was ist das?, and everything is dispelled. Pinto has no answer, can’t produce a single word, so he steps back too, the dance is finished. He bows to Kaspar, who wipes his mouth, clicks his heels, and leaves, leaving open the door behind him.

Pinto is not moving, gasping for air, as if he just caught up with the madness of the previous moment. Now he yearns, yearns for that which is forbidden to man. Das Licht ändert die Welt und jedoch bleibt sie gleich. The light swirls the dust motes in the air and shivers among the black and white squares on the floor, re-spelling everything into a new meaning, as though his mind has contracted deeper into itself and left a void for whatever was going to happen next. He is dizzy, his knees are weak; outside, the cheers are coming closer. What now?

He could lock the door and retreat into the depth of the Apotheke, into his life and past, and spend some time touching himself and thinking of Kaspar, who would thus become nothing but a story that he would repeat to himself, recollecting all the details that he could: the smell, the green eyes, the kiss, the taste of his lips. Or he could go after Kaspar, offer to take him around the city after all the Archduke fuss is over, show him the Čaršija and its ancient stores and temples, purchase some rahat lokum so that he could see sugar dusting on his mustache. They would stroll, and share secrets, and Pinto would take him to a back room at Hadži-Šaban’s kahvana, where they could have a few drinks together, let their lips do the talking, no one would bother them. But before Pinto can do anything or go anywhere, he’ll have to have another little drop of laudanum just to slow down his galloping heart. Laudanum will take care of everything.

As Pinto locked the door behind, he noticed that not only had he put up the black-and-yellow banner, but he had also put up the Bosnian red-and-yellow one; it was just that the banners were entangled and not unfurled—he reached to fix them, and a rush of colors dropped down upon him. A bright day, this, the kiss tingling on his lips, all colors aligning, summer light garmenting everything. He followed the Rittmeister down Franz Jozef Street, all the way to the Appel Quay, with no idea what he would do if Herr Rittmeister Kaspar von Kurtzenberger were actually to turn to him, look him in the eye, and say: Ich folge dir, wo immer du hinghest, Herr Apotheker!

Still, returning to the ongoing world was a magnificent thing to do, this splendid rolling forward into the future in obeisance to his heart and desire, away from—or deeper into—his own life, into a brilliant reticulation of unknown outcomes, toward Kaspar. To the place my heart must learn to love, there my feet take me. He could see the hackle on the helmet passing over the crowd—Kaspar was very tall—and he stopped at the corner. If he could find a pathway to him, he could say: Herr Rittmeister, it gives me enormous pleasure to inform you that the royal banner is presently proudly fluttering above the door of Apotheke Pinto. And if you would like me to show you our humble city and its Čaršija, just say a word and I am yours. Or I could make you a cup of Bosnian coffee in the back of my Apotheke, where it is quiet and no one would bother us. Just say a word. A clamor emerged from the crowd that suggested that something was unfolding, but Pinto just kept pushing deeper into it, until he was forced to stop.

There were two men now between him and the Rittmeister, at least one of them reeking of woodsmoke. There was an odd, mangy dog there too, pushing its way among people, as if on a mission. The Rittmeister stuck out in the crowd with his gorgeous uniform, lit up from inside by his heroic beauty. Pinto wanted him to turn around, see him in his wake, see him carried forth by dizeu. From behind, Pinto perceived the shining skin on Kaspar’s shaven cheek, and the point of his left mustache marking the spot where the dimple would be, and the straight horizontal hairline at the top of his neck. He envisioned two moves—parting the men, addressing the Rittmeister—that could get him close enough to inhale his rose scent; instead he inhaled the rancid smoke-and-sweat reek of the men before him. One of them was clearly an edepsiz, overgrown hair sprouting from under his filthy, loose collar. The dog must’ve been his. Off the other one’s shoulder an accordion hung like a dead animal, one key missing on the keyboard.

A car as big as a locomotive turned sharply from the Appel Quay and halted right before the Rittmeister, and Pinto instantly identified on the back seat the real Archduke, a helmet with peacock feathers over a gold collar with three silvers stars, and the Duchess in a dress so white it might have been fashioned from God’s garment itself, an even whiter hat with a veil, a bouquet of blue and white and yellow flowers in her arms. (History recorded that it was a gift from a Muslim girl, which for some reason brings tears to my eyes.) It appeared to him that Her Majesty smiled at Kaspar through the veil, as though recognizing him, while he bowed his head to her, and again Pinto’s heart raced ahead, and he had to take a deep breath lest he faint.

To the right of Pinto, a short young man, his hair also unkempt, a thin, strained mustache above his lip, his eyes sickly, pulled out a pistol. For a moment, no one could do anything nor move, even the dog stared at him in bafflement, while all of the reality hinged on that incongruous detail of a barrel pointed directly at Their Imperial Highnesses. The Rittmeister’s face tightened in stupefaction, the whole of it: the eyebrows and the mouth and the eyes somehow constricted and became bigger at the same time. The edepsiz reached for the young man’s gun—tiny tufts of hair on his fingers between his knuckles—and would’ve grabbed it if the other man hadn’t bumped him aside with his accordion, whereupon the shots rang, louder than a cannon salvo, and then the world exploded.

Rej muertu gera no fazi, the Sarajevo Sefaradim liked to say. A dead king does not make war, but a dead Heir Apparent to the Habsburg Empire and Inspector General of the Imperial Armed Forces does indeed. Within a few weeks, Pinto would be conscripted into the Imperial Army along with tens of thousands of other Bosnians. He would climb the slope of time while idling in endless meal lines, or while performing meaningless drills drenched in sweat. He would repeatedly recollect that precise moment just before the century of progress had disintegrated into these desperate days, and consider how differently everything would’ve turned out for everyone, particularly Their Royal Highnesses, if the man with the accordion hadn’t shoved the edepsiz, who would’ve then managed to grab the pistol and stop the young assassin. He wouldn’t be here now, constantly banging the rifle butt against his shins, nor would he be enduring dumb peasant jokes about his dark Arab face, about Jews and their avarice, nor listening nightly to Osman’s sawmill snore from the bunk above him, nor would he have left Manuči in tears and ripping her hair out as she remembered the future in which she never saw her only son again. Had the edepsiz grabbed the assassin’s pistol, Pinto thought time and again, he would’ve kissed Kaspar again, and—who knows?—maybe would’ve spent a few days with him, drinking tea and making love, and then, in some gorgeous future, they would live in Vienna, take their morning coffee at Café Olimpia, read the newspapers to each other, worry about European politics and live together in an endless world.

Yet, even before his basic training was over and his regiment deployed to invade Serbia, ...

Pinto took the laudanum off the shelf, knocking over the lavender tin, which miraculously did not break open when it hit the floor. He released a drop of laudanum onto a sugar lump, watched the brown stain bloom, then placed it in his mouth. While the sugar and bitterness dissolved on his tongue, he picked up the lavender, dipped his nose into the tin, and inhaled

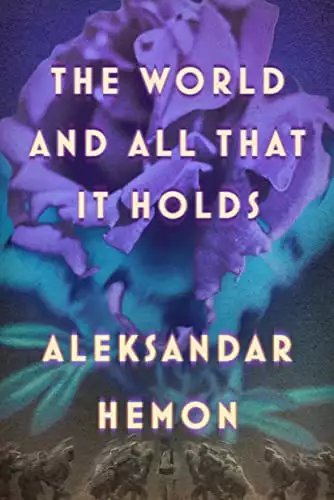

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved