1

Any witch worth her ginger is at least somewhat immortal. Trust the word on the street. So much easier to kill her, should it come up—she’ll bounce back, one way or the other. They always do.

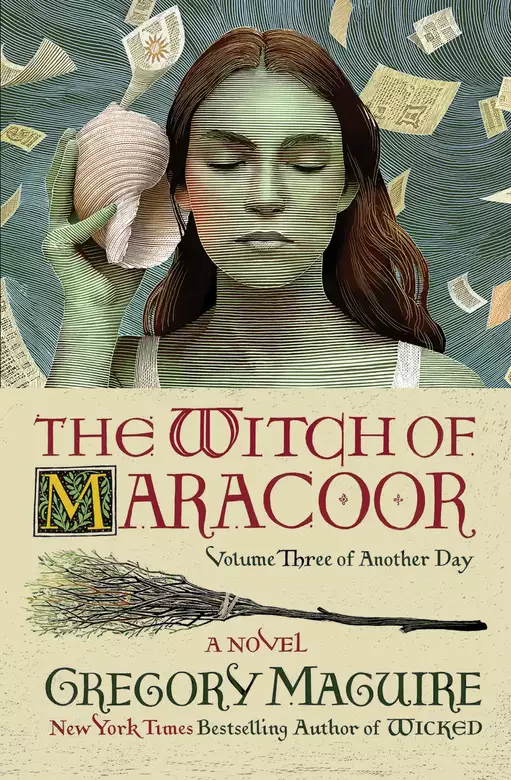

The Witch of Maracoor. That’s what some called her, whether or not she was actually a witch. The Witch of Wherever-It-Is-This-Time. A slur or a compliment, depending. The easier to identify, the easier to dismiss; who cares about her? Let’s go get our hands on a jug of beer.

Easy enough to see where the witch label came in. Hardly any deviation from stereotype. That green skin, the self-possession, even the take-no-prisoners manner of walking. (“She stomped herself across the Wool Exchange in that way she has—just so aggressive!”) Someone had heard her cursing once in an unladylike way—as if so-called ladies were ignorant of barnyard vocabulary. But was she a witch? How so? Language? Okay. And manners. Attitudes. Little attention paid to her clothes, for instance. Society forgives a woman everything but lapses in taste.

The Witch of Maracoor had appeared as if from nowhere, with her green-apple cheeks and that twitchy broom. Intent on some intrigue. Always unseemly and possibly seditious. Well, but when does a witch go in for community organizing? The singularity of her. She was like no one else.

Or she was like that Elphaba, revived. Perhaps? No? Maybe she was Elphaba, after all, come back from wherever she’d disappeared to. Few remembered the original Wicked Witch of the West from personal experience, but hardly anyone in Oz was agnostic about her. All those stories.

Her name was Rainary, this Witch of Maracoor. Her friends, when she had any, called her Rain. She lived under a cloud, and had done so for a long time. It was beginning to tell on her, though. That’s also where witchiness comes in—when temporary scar tissue turns into carapace.

It was the Goose, her familiar, who’d named her the Witch of Maracoor. Possibly it had been a joke. Or he’d been annoyed and in one slip of the beak he’d tarnished her reputation for good, forever. Or maybe he did it on purpose, setting her up to be able to clomp through a mob without having to trade in small talk.

The Goose had a lot to answer for. His name was Iskinaary. He’d flown with her in from—well, from wherever they’d originated. No one was sure.

2

A trim little windswift vessel called Ocean Heron, out of the Maracoor port of Tonxis, was headed for Great Northern Isle by way of Ithira Strand. Captain, crew, and three passengers: a middle-aged guy named Lucikles, this Rain, and the Goose. The crew was only four—no need and no room for more. The Captain managed all right. She claimed she was a former bootlegger up Regalius way, but her manner was more like an auntie glad for the liberty afforded by widowhood. Stalta Hipp; she refused to answer to “Captain Hipp” because she said that made her sound like the chaperone at a geriatrics’ picnic.

“You’re not going to find much on Ithira Strand,” she warned them. “It used to be a pretty enough haven, but since the Hind of the Sea imported a plague from Lesser Torn Isle, Ithira Strand has been avoided like—well, like the plague. We’ll anchor off Toe Hold first. It’s just across the strait. Reconnoiter from there. You, Goosemeat, you can goose yourself across the water and have a gander. Ha ha.”

“I flew across the damn Nonestic Ocean,” said Iskinaary, “and I’m planning on surviving to attempt the return journey. If I must make a sortie, it’ll be brisk. I’m not interested in carrying a fatal disease back to Oz. Except in a few dedicated cases that I won’t go into.”

Ithira Strand had long been home to a species of bird called the border crane. Lazy, the cranes preferred sorting through village garbage to fishing. At the moment, though, few border cranes remained on the island, the rest having migrated when the human population disappeared from disease first and then panicky exodus.

One such creature had been known as Silverbeak for, in a biological misfiring, her bill gleamed like polished weaponry rather than the ordinary muddy pewter. Like all her kin, her eyes were encircled by a bright red cap that cupped her head. A robber bird in a party mask. The effect lent her an air of keen intelligence that was possibly unmerited—otherwise wouldn’t she have left with her tribe?

Little can be said about what an animal perceives. Without spoken language, a creature’s concepts of time and history, or of consequence on any scale beyond the flock’s immediate well-being, remain unknowable. The habits of animals: instinctual and emulative. To be sure, animal personalities emerge. That brindle cow is the ornery one; this duck alone seems to be scared of the water. But is there such a thing as a lazy spider, a songbird gone mute on a hunger strike, a puppy born with a radical instinct for guile? Few humans can ever say. And animals aren’t talking.

For whatever reason, Silverbeak held to her sentry post on Ithira Strand, unflinching as a bronze, when Iskinaary arrived across the strait from Tea Stone. The Goose carved his first circuit above the harbor. The crane didn’t appear to follow his flight path by tracking him with red-circled side-eye. The dusky hour was coming on. Better for fishing. Dinner took precedence.

After the Goose had flown on, Silverbeak moved into the water. The line where light and shade met on the sandy bottom made movement easier to distinguish there. It wasn’t long before she spotted a glint some ways off. Her legs angling in slow, splashless

movement, she paused as if to pose no threat, and then she lunged. A nice-size stickleback. She stood with it pinched midway up her beak. It flapped noisily enough that two seagulls came in at an angle, hoping to scare Silverbeak into dropping her catch. She didn’t flinch. She lifted her head and let supper drop farther along her bill toward her throat. Then, one gulp and down the gullet. Distending the elastic skin of the crane’s neck, the meal thrashed in protest.

Silverbeak stopped eating when the Goose descended into the water in that collapsing way geese have. The Goose folded his wings upon his dorsal feathers and ruddered his tail feathers ostentatiously. He neared her. She kept her eyes on several horizons and didn’t acknowledge him.

“I don’t suppose you have a word of welcome for a traveling stranger?” he said.

It seemed she did not.

“You won’t mind if I help myself? I prefer insects and weeds, but the offerings on board a seafaring vessel are, shall we say, limited. Something fresh from the shallows would do nicely.”

The light lowered; a cloud trailed its hem across the sun.

“After weeks of human society, I was hoping to kick back with my own kind, or near enough,” he added. When Silverbeak showed no interest in him, the Goose gave himself over to supper. In elegance of execution he was no match for the crane. He caught a tarnished item quickly enough—his male pride satisfied in front of this female from another tribe. He thwacked it on the surface of the water, worried it about, dropped it three or four times, bloodied his beak. This was normal procedure. Iskinaary wasn’t self-conscious about it until Silverbeak spotted a morsel with which to finish her meal, and took two patrician steps forward before securing a much larger specimen. With the calm of a priestess she stood there letting it thrash, its moment of sacrifice extended—was she showing off, wondered Iskinaary—before she smoothly gobbled it down.

“You have the look of someone who knows more than she’s saying,” said the Goose.

When the border crane took off, it was with a single step forward into the air. Her wings extended eight feet—a third again the span of Iskinaary’s. He followed her with the traditional dashing-on-water takeoff that could look stupid even to him. When he was younger he could do it in only six steps. Now it was more like twelve. He’d be lucky to make it back to Oz—at the rate he was aging he might have to walk home across the ocean.

He followed the lean pretty thing at a distance, not wanting to frighten her, not ready yet to go back to his companions on the ship. Could she be a Crane—a talking creature? Regardless, the company was welcome, even if she didn’t have much in the way of social graces. Her habits might teach him something about the island it was useful to know. That’s what he said to himself.

The town of Ithira Strand strung itself out along two roads running parallel to each other and to the sandy verge. For a place eviscerated by plague not so long ago, it was kempt, as if the breeze had taken over the job of sweeping the streets. The doors were mostly closed, the windows shuttered. One might

have expected packs of wild dogs, but perhaps the Ithirians had taken their dogs with them. Or had the hounds succumbed to plague, too? The thought of this made Iskinaary distinctly queasy, and he was about to turn back when he saw three old cats reclining on a flagstone plaza in front of a padlocked café of some sort. Cats can be sort of eternal, like witches, but these looked too disaffected to bother to die and come back. Iskinaary found this a little encouraging. Though it was a stretch.

And the Silverbeak—the same name came to Iskinaary, it was inevitable, an obvious and reductive name like Gimpy or Shrimp or Carrot-top—Silverbeak lived here too. For there she was now lifting, upon those white wings as pure as faith, and settling athwart a bracken nest perched upon a listing chimney stack. Maybe she had some stork in her lineage. Or maybe she was wary of old cats.

Where there was a nest, there would be eggs, or even baby colts. A sign of life. If not now, soon. Iskinaary didn’t realize he’d been holding his breath. He decided to visit Silverbeak by flying up to land on the roof-beam just beside the shoulders of the chimney.

“I suppose you’re wondering where I’ve come from,” he said. “Can’t be too many Geese making their way from any mainland to this northern isle.”

Silverbeak set to work revising the fringy edge of the nest. She didn’t reply but she didn’t fly away either. So Iskinaary told her about the long trip from Oz, and his companion, Rain, and their hopes to make it back home safely. The border crane listened without making snarky remarks. When the Goose finished, he sat in silence. She was regarding him with a level look, neither vicious nor welcoming. He’d never met anyone so serenely herself.

The others bobbing off the shores of Toe Hold, or maybe collecting fresh fruits on the island itself, would be waiting for a report. Let them wait. What an unexpected vacation, to sit in complacency with someone who didn’t answer back. Look at that slender neck against the burnt-orange sky.

3

On Toe Hold, while they waited for the Goose, Rain wandered away to find a pond shielded from the eyes of her companions. Lucikles, the nominal ambassador of the court, now at loose ends, began to rehash his recent adventures to the affable Captain.

Stalta Hipp relaxed with a beaker of sour ale and smiled her appreciation for a tale of woe that for once hadn’t happened to her. “I’m a good listener,” she said. “If our friend the chatty Goose is taking his time over there, spin out the tale as long as it takes. What else are we going to do? You don’t want to hear me sing a tiresome roundelay of my life as a smuggler.”

Much of what had happened in the past several months Lucikles considered privileged information. State secrets, if you wanted to go that far. The devotions practiced by the brides of Maracoor, and their untimely interruption. (Or was it, precisely, timely?) The cross-country pilgrimage to visit the Oracle of Maracoor, out in the unmapped western regions of the nation. The disposing of the lethal item known as the Fist of Mara. The abdication of the Bvasil from the throne.

So Lucikles talked instead about the return to the western slopes of High Chora by the subdued party of adventurers. Only five of them left by that point. Filthy, dispirited, hardly speaking to one another. Rain and the Goose. Lucikles with his newly adolescent son, Leorix. And finally, the palace representative, a handsome young man named Tycheron, who’d shown a romantic interest in Rain until he’d seen her fly, at which point his skepticism about romancing a witch got the better of him.

And on the way back cross-country, the travelers saw only glimmers of the secret world of the homegrown Maracoorian spirits. Where once there’d been apparitions of piskies and minor deities, scraps of Maracoor’s fabled past, now Lucikles could detect only a sweet decadent odor, as if something questionable had recently passed by. A quiet had begun to settle upon the land. Evidence of repair and restoration, Lucikles hoped, rather than an indication of some sort of final coma.

And why not? He savored any signs of revival. Look, while harboring in the enchantment of the western woods, even Rain had made some recovery. Her drowned broom had been restored by the so-called Oracle of Maracoor; she’d proven her ability to fly in front of them all. With less commotion than the Goose could do, she’d mounted the air. She’d swept the tops of the trees with the business end of her broom, raising clouds of powdery pollen. She’d swung back in a loop to collect it, using some old seashell as a kind of scoop. Quite a sight, Lucikles did admit it.

“I don’t know about this witch business. Are you talking the get-up, or the make-up, or the giddy-up with the broom?” asked Stalta.

“Can you fly on a broom?”

“No. But piloting a ship and plying the waves doesn’t make me a mermaid. Just what is it that seals this girl’s identity in your mind?”

A good question. A witch was a concept—like most concepts—with forgiving outlines. But a witch was more than a certain kind of ornery one-off, to be sure. A witch possessed a capacity for rawness coupled with a strength of charm—the ability to cast a spell of sorts.

True, many old wives could do much the same with their fingered portions of ground herbs and oils. The muttered chants, the candles and incense for atmosphere—that was histrionics, surely. (Surely?) The real proof was in the person. And Rain, for all her confusion, her amnesia and recovery from it, was a live thread of capacity. A sprig of green

lightning in stout boots and a walking cape.

Lucikles said, briskly, “She promised our hosts to bring their unspent pollen to Ithira Strand and to try to sow it there before she continues her trip home.”

“This Oz that she keeps mentioning.” Stalta belched; the brew was rough. “What do you make of such a thing?”

“I never knew there were lands beyond the ones it was my obligation to oversee—the Hyperastrich Archipelago, the Great Northern Isle, and so on. I thought that was as far east as the world went, and the Sea of Mara stretching beyond was too vast to be knowable. We all did. The Bvasil did, and all his factotums and courtiers beside. This notion of a possible Oz makes me feel—crowded. The policy from the Crown, so far anyway, is to keep the matter very hush-hush-hush-a-bye.”

“So tell me, do you even believe in Oz? I mean, how trustworthy is this off-color girl-thing anyway? With her trick Goose being so chatty and all that? It’s true she has an accent, but so do the Skedelanders and the Pomiole clans and most people who are more than seventy years old. Anyone can fake an accent.” In a parody of up-country drawl. “Oy coin dyoo its moisef, whens Oy heff thay moind tyoo.”

“I don’t know what to believe, I don’t even know what belief is,” said Lucikles. “A few months ago I’d have said I hardly believe in the Great Mara except as a relic of our cultural identity. But in the past few months I’ve traveled with a couple of annoying harpies. I’ve met up with a giant who emerged from the earth like a laborer waking up from a drunken stupor. So I’ve retired my skepticism and replaced it with—a more refined skepticism, I guess. Oz may be, or may not be. Does it make a difference to me now?”

“Following your interview with that Oracle, you left him and started back, scaled the cliff to High Chora,” Stalta reminded him. “But what happened next?”

“It’s easy to telescope. We hot-footed it cross-country toward my mother-in-law’s farm at the eastern breast of the plateau. We sidestepped a few Skedelander contingents, lingering remnants of the invaders, who were still on the hunt for that treasure removed from the capital. Once, they surprised us on the path of a roistering brook. The noise of a cataract had cloaked the sound of our approach, and theirs too. They raised their weapons until they got a good look at Rain. Then they stepped aside and let us pass. I think the steam was going out of their search.”

Stalta Hipp arched an eyebrow. “You’re not telling it all to me, are you.”

Well, the Captain was on to him, and no mistake. It had been an encounter, all right. Lucikles hardly liked to envision Rain, suddenly enraged, like a cat seeming twice its size. Holding slantwise on to her broom, she’d lifted in the air a few feet. The Skedelander contingent—some soldiers in breastplate and helmet, others shucked free of their heavy chained mail and sweating in their torn and greasy tunics—had quailed and then rallied. ...

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved