- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

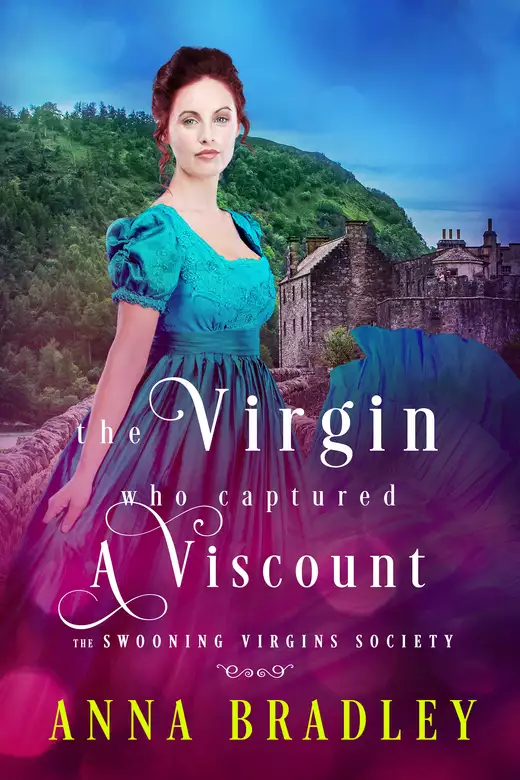

Synopsis

Behind the buttoned-up façade of The Clifford Charity School for Wayward Girls reside some of London’s most brilliant ladies. For the extraordinary young women of the secret Swooning Virgins Society are capable of taking down an utter scoundrel —or redeeming an aristocrat worthy of a woman’s love . . .

On a dark street in London, Mairi Cameron finally tracks down Daniel Brixton, the childhood friend who mysteriously disappeared from her Scottish hometown years ago. Now, however, he’s an arresting stranger whose life she promptly saves. But rather than being grateful, Daniel doesn’t believe Mairi is who she claims to be—or that her dear grandmother stands accused of his murder. Mairi is desperate to convince Daniel to return to Scotland with her, not only to prove he’s alive, but because of the strong feelings she still harbors for him. . .

The Swooning Virgins Society quickly goes into action, and standing before them, Daniel is convinced to help--if only to stay near the alluring Mairi. Posing as her husband for their travels only escalates the passions between them. And once Daniel faces the dark truth of his past, he must decide if he’s ready to claim a new future—with Mairi his side . . .

Praise for Anna Bradley and The Virgin Who Humbled Lord Haslemere

“Flirtatious banter and intelligent characters fill the pages of this sensuous novel. Historical romance fans will be delighted by Bradley’s clever combination of mystery and romance.”

—Publishers Weekly

Release date: October 4, 2022

Publisher: Lyrical Press

Print pages: 320

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Virgin Who Captured a Viscount

Anna Bradley

Coldstream, Scottish Borders

July 28, 1772

Ye go poaching on Lord Rutherford’s land again, Daniel’s father had said to him this morning, and I’ll redden your arse tonight. Ye ken, lad?

The lord’s gamekeeper was already after him—ten, maybe twelve paces behind, his old man’s lungs huffing and puffing like a cracked bellows. Murdoch had caught Archie Mackenzie last week and whipped him something awful, ten bloody stripes worth, but old Murdoch wouldn’t catch him, because Daniel was quicker than lightning, the fastest runner in Coldstream. Maybe the fastest in the county, even. Faster than Archie, no matter how much Archie bawled about it.

He gulped air as he ran, wild, gasping breaths that tore his throat on the way up, the dripping bag with the three fish he’d plucked from the pond bouncing against his thigh with every stride, leaving a damp patch on his breeches, and behind him the slap of Hamish’s bare feet striking the hard-packed dirt, slap-thump, slap-thump, his bad leg dragging behind him, but still faster than Murdoch, for all that Hamish was lame, and got tired quick.

The other boys used to tease Hamish sometimes, called him a cripple, but Daniel had put a stop to it by thrashing ’em. Tore up his hand on one of Archie’s sharp teeth doing it. It bled like the devil, too, but he’d have done the same again, as many times as it took to shut Archie’s big mouth, because Hamish was the best friend he’d ever had.

They were close as two brothers. They’d sworn to it, the day he turned eight. They’d spat on their palms then clasped hands, because that was the way you did it. It didn’t count if you didn’t spit first. Not spitting was like cheating, and everyone knew only cowards cheated.

He danced between the patches of dappled sunlight filtering through the trees above, leaping over gnarled tree roots and ducking under the thick branches. The tree line had turned from a green blur into leaves and branches before he noticed the slap-thump behind him had stopped.

The mud was fresher under the trees, unbaked by the sun, and his foot slipped in the slick muck. He fell to his knees, cursing at the ooze soaking into his breeches, and peered around the massive trunk, the rough bark sliding against his palms.

Hamish was still coming, but his steps had slowed, and his face was twisted with panic. If Daniel ran now, he could save his own arse from a striping, but a real man didn’t leave his brother behind, even if it meant Murdoch would tear the skin from both their backsides, cackling with every lash of his horsewhip, his blind eye, all white, rolling around in its socket like a runaway billiard ball.

Archie had told him Murdoch could curse a boy with one blink of that eye. Daniel had called him a liar, right to his face, too, but Archie had sworn to it. He said he’d seen Murdoch curse a boy once—one twitch of his eyeball and the boy had dropped where he stood, good as dead.

Daniel clutched at the trunk of the tree, slivers of loose bark digging under his fingernails, and muttered a few words he remembered from the bedtime prayer Mrs. Cameron had taught him. He could stop a curse that way, couldn’t he? Stop Murdoch’s evil spells from raining down on Hamish’s head.

Now I lay me down…now I lay…if I should die…

Then, when that didn’t work, “Come on, Hamish. Run.”

But the gamekeeper was getting closer, his huge hand reaching, clawing the air just behind Hamish’s neck, the slash of his mouth opening in a bloodthirsty grin as he caught Hamish by the shoulder and wrenched him off his feet with one vicious jerk. “Got ye, ye little whelp.”

Hamish’s shriek bounced off the trees, everywhere at once. Heat rushed into Daniel’s chest, burning him, battering against his ribs, his own shriek tearing loose from his throat, echoing Hamish’s cry, as if a scream could make the man stop, make him leave Hamish alone.

He dropped into a crouch, muscles tensed to burst from the trees and pummel the man into the ground, but he had Hamish by the throat, and he was shaking him, shaking him like a hound with a fox, Hamish’s body dangling from the grip of that crushing fist, feet jerking, and Daniel froze, his stomach pushing into his throat, because if he moved, that man would catch him, and shake him just as he was shaking Hamish, and he’d go limp and still, only his feet moving, swinging back and—

“Not a word, Daniel.” A hand clamped over his mouth, the rusty taste of blood hit his tongue, and a voice, low and frantic, whispered close to his ear. “Come with me, quickly.”

“No! Hamish!” A real man didn’t leave his brother—

“You do as you’re told,” she hissed, then she shook him hard enough to rattle his teeth, her fingernails sinking like hooks into his shoulders.

He gaped up at her, tears stinging his eyes. She’d never shaken him before, had never even raised her voice to him. Had his father sent her to fetch him for a whipping? It was all jumbled inside his head—the pond, the fish, his father’s warning, Hamish’s feet dangling—but it was wrong, wasn’t it, to shake a boy for stealing a few fish—

“Quickly, Daniel. There’s no time to waste.” She seized his arm and dragged him deeper into the woods. Tree branches snagged his hair and left long, bloody scratches on his face and arms, but she urged him to go faster, faster, pulling on him until at last they broke through the forest and came out on the road on the other side.

His father was waiting for them in their wagon as they burst from the woods, with their few possessions piled haphazardly into the bed, and that was wrong, so wrong, that his father should be here instead of pounding iron at the forge, and the look on his face…

Daniel froze. His father was a big, strong man, but he’d shrunk since this morning, his shoulders pulled into his chest, like an old man’s. His father had looked that way only once before, three years earlier, when he’d taken Daniel aside and told him his mother was dead.

He wanted to go back to Hamish, where the trees were rustling in the breeze, the birds were twittering, and everything made sense, but Mrs. Cameron was dragging him to the wagon, saying…something, but he couldn’t make any sense of it.

After that, it all happened too quickly for him to wonder anything more. Mrs. Cameron snatched him close and pressed a kiss into his hair, her arms so tight around him his lungs ached. “Be a good lad, Daniel. Promise me?”

He nodded, his words all gone, his lips numb, and let her hurry him toward the wagon. His father grasped his arm and hauled him onto the seat, and an instant later they were moving, wagon wheels creaking against the rutted dirt road.

He only looked back once, but by then Mrs. Cameron was gone, the hem of her gray skirts vanishing into the trees.

* * * *

Mairi tumbled out the window and landed on her hands and knees in her grandmother’s strawberry patch. She’d tried to be careful where she landed, because strawberries were her favorite, but a crushed berry had left a sticky red smear on her hand. She spat into her palm and wiped her hand on her pinafore, but now she had a red smudge there instead.

“Damn.” It was a bad word, a curse, but no one was around to tell on her, because Daniel and Hamish had gone fishing without her.

They always did, and it wasn’t fair.

She’d given them her saddest face, begged and pleaded with them to take her along, but they’d gone off this morning without her, as happy as anything. Daniel had even been whistling.

Whistling!

He was a mean, wicked boy, and Hamish…well, Hamish was sweet, better than summer strawberries, but he’d let Daniel leave her behind, all the same. He said she was too young to go to the pond, that it was dangerous, if she fell in.

She wasn’t too young. She was turning six years old tomorrow, and anyway, she knew how to swim.

Mostly.

But she didn’t need them, anyway. She’d just go to the pond on her own, and have an adventure all by herself. She’d been doing it all summer, ever since she found out that if she stood on the bed, she could reach the latch on the window beside it. It stuck halfway up, but she could wriggle through the gap, then plop! She dropped right into the back garden.

She picked her way through the strawberry patch, jumping from one foot to the other so as not to spoil any more of the plump berries hidden under the tiny white flowers, their dark green leaves huddled together in threes.

Her grandmother would scold something fierce if she found out Mairi had gone to Rutherford Pond. It wasn’t really called that, but she tried to remember to call it that in her own head, because her grandmother said you had to give the lord his due, even when he hadn’t done anything to deserve it.

But she hadn’t promised she wouldn’t go, so she wasn’t doing anything bad, not really, and she wouldn’t go near the water. She’d just peek through the bushes and see if she could see Hamish and Daniel.

They were always together, whispering and laughing, because they were best friends.

Her belly had twisted with something ugly when Hamish told her Daniel wanted to be his best friend, because she wanted Daniel to be her best friend, but she’d worked it out in her head, and maybe it was fair, because Hamish didn’t have many friends, and she had dozens and dozens of them, so it was maybe all right if Hamish had Daniel.

The pond was just through the trees, but she had to go through the brambles to get to it, and they tore at her legs, leaving stinging cuts behind worse even than splinters, but she wasn’t crying, even if her eyes did tear up just a little. She wasn’t a baby who cried at every hurt, no matter what Daniel said.

She dragged her sleeve across her eyes, and pushed her way through the thicket of weeds and scraggly bushes, but when she got to the spying place, where you could see the pond through the trees, Daniel and Hamish weren’t there. No one was there. It was just the bugs chasing each other around in circles over the muddy water.

Stupid, boring pond. The only thing worse would be going back to the stupid, boring, empty cottage after she’d gone to all that trouble to get out the window. Daniel would laugh at her if he found out, but it was chilly in the shade of the trees, and she was hungry, and she didn’t want her grandmother to catch her near the pond.

She turned to scurry back the way she’d come, but a branch snapped, and the leaves rustled like someone was moving through the forest, so she crept along after them, winding her way through the trees.

She walked for a long time without seeing anyone, until at last she came out at the little clearing at the other end of the wood, her boots skidding over the leaves, and there they were, Daniel and her grandmother, right there in front of her, standing on the road, Daniel tucked into her grandmother’s arms. Mairi couldn’t see her face, because it was pressed into Daniel’s dark hair, but her shoulders were shaking, like they had when Daniel’s mother died.

A chill grabbed her neck, gooseflesh prickling her skin.

Daniel looked scared.

But Daniel was never scared, not of anything. He was the bravest of all the village boys, the bravest boy she’d ever known. A bad taste rushed into her throat, bitter like wild cherries, but just as she opened her mouth to call out to them, her grandmother released Daniel and gave him a gentle push toward his father, who was waiting on the road in his wagon.

The reins snapped, the horses’ hooves kicked up little clouds of dust, and then they were gone. She didn’t take her eyes from the wagon until it faded from sight, swallowed into the tunnel of trees that lined either side of the road.

By then, her grandmother was gone, vanished back into the woods without a sound.

Mairi stood staring at the place she’d been, her mouth open, but she felt scared now, so she ran home, scrambled back through the open window and closed it tight behind her, so no one would know she’d ever been gone. She flopped down in the center of the bed, pulled the quilt over her head, and closed her eyes, but she could still see Daniel’s face, and her grandmother’s` shaking shoulders.

Her grandmother wept that night, after it got dark, her back to Mairi, her face pressed into the pillow. Hamish didn’t come back that day, or the next, or the day after that.

Daniel never came back, either.

After a while, Mairi stopped asking where they were, when they were coming home. Her grandmother never spoke of them. Mairi might have believed she’d forgotten them, but every night after they’d gone, after her grandmother tucked her into their bed, she’d weep, quiet, ragged, broken sobs that dragged babyish tears from Mairi’s eyes.

It wasn’t right, that they’d left like that. Not right, that they’d taken her grandmother’s joy with them when they did.

Stole it.

Some days, when she woke to her grandmother’s red-rimmed, swollen eyes, the fist inside her chest would clench and squeeze until the knuckles bulged and the sharp fingernails clawed at her ribs, and her heart would shrivel into a dry, empty husk to make room for it.

Those days left long, jagged, bloody scars inside her. On those days, she hated Daniel and Hamish. Other days, she longed for them both with an ache nothing could sooth.

On those days, she hated them more.

Chapter One

No. 26 Maddox Street, London

Early February 1796

Daniel prowled amongst the thick shadows at the edges of Lady Clifford’s drawing room, rubbing his fingers over the smooth pearl handle of the dagger he’d slipped into his coat pocket.

It was one of two, a gift from Lady Clifford. They were fine ones, perfectly balanced, the hooked blades sharper than an eagle’s talon. Pretty, too. Their gleaming edges caught the light, so whoever was on the slicing end could see them coming.

He’d tucked the other one into his boot just before he’d been called into dinner.

Ten courses tonight. Nine too many, and two hours too long. He’d eaten little, said even less, instead keeping his attention on the window on one side of the room, the sky darkening behind the thick panes of glass.

It was dark, but not yet dark enough. Not for what he had planned.

Lady Clifford and the girls—nay, not girls, they were ladies now—were dressed in blue tonight. A man might think there were only a few different shades of blue, but he’d be wrong.

Then there was Lord Haslemere, trussed up like a peacock in a waistcoat such a bright blue it singed Daniel’s eyeballs. No blending into the shadows in that waistcoat.

Daniel was in black, as always, a dark, solitary island surrounded by an ocean of blue silk, rippling and eddying in the firelight.

“For God’s sake, Brixton, I’ve hardly had a glimpse of your face this entire evening.” Lord Lymington waved him toward the fire, a goblet of port balanced between his elegant fingers.

Daniel had refused the glass offered to him. His own fingers were rough, scarred things, too thick to be elegant. No goblet was going to change that, no matter if it did have gold filigree…angels? No, cherubs, of all bloody stupid things, etched around the rim.

“You don’t intend to skulk about in the shadows all night, I hope. You’re the sort a man likes to keep his eye on, Brixton.” Haslemere swirled the port in his goblet, the blood-red wine dripping down the sides of the crystal bowl. “I despise it when you skulk.”

Daniel slitted his eyes against the offensive glow of lamplight spilling into the drawing room, and retreated deeper into the gloom. He’d done a bloody poor job of skulking, if a dull-wit like Haslemere could still see him.

“Come, Brixton. It’s baby Amanda’s birthday. She’s three months old today, and you haven’t held her once since she was born.”

Lord Gray, this time. An earl, and irritating enough with that smirk, but not as irritating as Haslemere. No one was as irritating as Haslemere.

As if he’d heard Daniel’s thoughts, Haslemere gave him a provoking grin. “Don’t tell us you’re afraid to hold her, Brixton.”

Afraid? He wasn’t afraid of anything. Not villains lurking in dark alleys, not knives, swords, rapiers, or any other sharp, pointed objects. Not pistols, fists, brawls, or bullwhips. There was a reason the sight of him was enough to send London’s black-hearted villains fleeing into the night. “Nay.”

“Hush, Lord Haslemere. Of course, he isn’t afraid.” Sophia, now the Countess of Gray, approached his corner, carrying a squirming, mewling creature wrapped in a white blanket, the downy head tucked in the crook of her elbow. “Here she is. Hold out your arms.”

Daniel kept his arms at his sides. If he didn’t raise them, no one could put anything into them.

“Please, Daniel?” Sophia turned wide, pleading green eyes on him.

Christ. Not the pleading eyes. Anything but that.

He’d taken a pistol ball to his cheek once. It had only grazed him, but it had scorched like fire, bled like the devil, and left a nasty scar, too. He hadn’t even flinched, but one glance from the eyes felled him every time, worse than a blade plunged into the center of his chest.

They knew it, too. Shameless chits.

What the devil was wrong with Gray? Why wasn’t he putting a stop to this? Any man worth a damn would refuse to turn his precious infant daughter over to a conscienceless blackguard like Daniel, but Gray didn’t say a bloody word, just stood there nodding.

He swallowed back another refusal and trudged toward his doom, gaze averted from the wrinkled, pink creature in Sophia’s arms, the tiny, spindly fingers gripping the edge of the blanket.

Sophia gave him her most winning smile. “Hold out your arms.”

No sense in fighting it. He stuck his arms out in front of him, and waited for it to be over.

“You needn’t look so grim. She’s a baby, not a poisonous snake.”

A baby. A soft, defenseless little thing with a head no bigger than his palm. He’d prefer a poisonous snake, as no one was likely to mind if he dropped it, or squeezed it too hard. His huge hands had no business touching such a delicate, innocent creature.

The girls—that is, the ladies—all crowded closer as Sophia placed the squirming bundle in his arms. “There. That’s not so terrible, is it?”

“Oh, look!” Cecilia beamed at him, one of her hands moving to cradle her own swollen belly. “She’s smiling at you, Daniel. I’m certain she recognizes you.”

“That’s a yawn, lass, not a smile.” Or worse, a yawn one breath away from becoming a wail. He stared down at the baby, gut rolling with every twitch of that soft, open pink mouth. He could already hear the ear-blistering shriek ringing in his head.

Sophia leaned closer to get a better look at her daughter’s expression. “Nonsense. Of course, it’s a smile. She loves you already.”

“She does,” Georgiana echoed stoutly. “Why shouldn’t she?”

Dozens of reasons. Nay, hundreds. Too many to list, so he settled for a grunt.

“Doting uncle, indeed.” Lady Clifford stood a little aside from the rest of the group, watching him, no part of the scene unfolding before her escaping her notice. “The first of many nieces and nephews.”

She said no more, but he wasn’t fooled. They’d known each other too long for that.

She didn’t say, everything’s changing. She didn’t tell him he’d have to bend and twist and squeeze until he’d made a place for himself here, but the warning was there, hiding between the words she spoke aloud.

He’d long since learned to listen for what she didn’t say.

He was handy with blades, pistols, and his fists, but he’d never been good for much else, especially anything tender, breakable, like the feeble little bundle he held in his arms, with her soft skull and thin, fragile bones.

“Here, ye take the wee lass now.” He held the baby out to her mother before he dropped her and she shattered, his throat clenching with an unfamiliar rush of panic, and pretended not to see the disappointment in Sophia’s eyes, so it couldn’t reach the few remaining tender strips of flesh around his hard heart. “I’m going out.”

He strode from the room as soon as Sophia took the baby out of his arms, but Lady Clifford’s determined footsteps followed him down the hallway, and her soft voice stopped him before he could flee through the front door. “Where will you go tonight?”

“Guess I’ll know when I get there.”

“Is there anyone in particular you’re chasing? Someone I should know about?”

“Nay, but it’s a dark night. Plenty of criminals on the streets, I reckon.” It was true enough—criminals were a plague on London, much like rats—but it wasn’t what she’d asked, and sure enough, her brows lowered and her blue eyes narrowed, just as they always did when she was annoyed.

“I would think we had enough trouble without you going in search of it. You must do as you will, I suppose, but keep in mind, Daniel, that chasing shadows won’t solve your difficulties. They’ll be waiting for you when you return.”

“No reason to bother with them now then, is there?”

He owed her better than that, but the thick darkness was waiting for him just on the other side of the circle of light that spilled from the hallway, tempting him. He sucked in a deep breath of frosty air as the night settled over him like a familiar hand against his neck, warm and reassuring, right up until it turned into a fist, tightening and squeezing…

That was when he liked it best. Odd, how a man could become accustomed to ugliness and violence, comfortable in it, in a way he never could be in a drawing room. The night surrounding him, the damp cobbles under his feet, the wind sliding icy fingers under the edge of the collar of his cloak made sense, soothing his jangled nerves.

His steps took him past cramped alleyways toward the other end of the city. As he neared St. Giles, the stench of chamber pots emptied onto the already filthy streets assaulted his nose.

If a man wanted a fight, he’d find it here.

Or it would find him.

His quarry was nameless, faceless. A new enemy, not one of the usual scoundrels he’d reduced to a bloody smear on the streets so many times before. He’d told Lady Clifford the truth about that—he wasn’t after one of their usual blackguards—but he hadn’t told her all of the truth. He’d neglected to mention that for the past few days, someone had been chasing him.

Or not chasing so much as following him, watching him. Whoever they were, they’d kept their distance. They were stealthy, skilled at slipping around corners and down darkened passageways, someone who knew how to blend into the background, and hide in plain sight. Otherwise, he would have caught them days ago.

But they wouldn’t stay hidden forever. They never did.

It could be anyone. He had a great many enemies in London.

He lingered at the junction of the seven streets where the sundial used to stand, just for long enough to be seen, then headed west down Little Earl Street toward Monmouth, whistling, but he was listening, waiting for any sign he was being followed. Not anything ordinary, like the sound of footsteps, or a glimpse of a figure darting just out of sight. Seven Dials was always a confusion of bodies and noise, especially on a dark night like tonight, but for something much more subtle, his senses honed by years of wandering these streets.

A telltale chill at the back of his neck, a spray of gooseflesh from a stranger’s eyes crawling over him, following his every move—

There.

Just seconds ago, there’d been nothing, and then it appeared as if born from the mist itself, the hairs on the back of his neck standing straight on end. He didn’t turn, nor did he slow, but he palmed the handle of the blade buried deep inside the pocket of his greatcoat.

He led his quarry past Monmouth Street—too many people about there, and too much light—and toward the narrow maze of streets overshadowed by tall, shabby buildings crowded together, leaning on each other for support.

He could hear the footsteps now, behind him, a muffled tread, lighter than he’d expected. His pursuer was small, then—much smaller than he was—but agile and quick.

Without warning, he darted to the right, blending into the thicker shadows cast by one of the buildings, and waited. The footsteps behind him ceased, and he imagined his pursuer pausing at the entrance to the courtyard, weighing his options. Only the faintest trickle of light illuminated the darkness here. There were people about, but the poor souls who inhabited the crumbling buildings were people of the night, just as he was, and long since hardened to others’ distress.

They wouldn’t come running, should anyone cry for help.

So, he waited, poised to spring, but his pursuer was clever enough to see it was too dangerous to follow a man his size into a dark alley, because he didn’t appear, and a few moments later Daniel heard the distinct sound of retreating footsteps.

Running, this time.

He leapt out from his hiding place just in time to catch a glimpse of the hem of a dark cloak whirling out behind a fleeing figure, and he took off in pursuit, his much longer legs eating up the ground between them.

It was a mistake to run. He’d chased dozens of blackguards through these streets, and knew what lay behind every corner and down every alley, as surely as he knew the patterns of scars across his knuckles.

There would be no escaping him now. One way or another, this would end tonight.

His pursuer—now the pursued, the tables having been neatly turned—fled back the way he’d come, across Grafton Street toward Newport Market, then scurried into another dark courtyard adjacent, with Daniel right on his heels. When he reached the entrance to the courtyard he paused and peered into the gloom. He’d expected the man to pass through to Porter Street, where he had a better chance of losing Daniel in the crowd, but he hadn’t.

He’d stopped in front of one the hovels, and seemed to be frantically scrambling with the door.

Surely, the man hadn’t led Daniel to his home? He must know he wouldn’t find any refuge there. Daniel could crash through the flimsy door with one well-placed kick.

His spine tingled with warning, but he was so close, nearly had the man in his grasp. It might be a trap—there could be a dozen blackguards waiting to leap upon him on the other side of that door—but they’d come after him either way, and he had yet to fall into a trap he couldn’t batter his way out of.

The wood of the door splintered under his boot heel, what was left of it crashing into the wall behind it. The hem of the dark coat whirled past him, but Daniel caught a handful of wool in his fist and jerked the man backwards by the cape of his greatcoat, only…

It wasn’t a greatcoat at all, but a woman’s cloak, and the bunched wool in his hand wasn’t a cape, but a hood, and inside the hood was a girl—woman? with wild locks of red gold hair, a pale face with dainty bow lips, and eyes so wide and blue they could sink a man, and make him grateful for the drowning.

He fell back a step, mouth dropping open. “What the dev—?”

He didn’t see the dull gleam of the pistol until the instant before it crashed into his skull. He staggered backward, his arms flailing, grasping at air. He got one hand on the girl before a second blow sent him to the floor. His fingers went limp around the fold of her cloak, and he tumbled into a deep, silent darkness.

Chapter Two

He hit the floor with an almighty crash, like a tree falling—a tree that hits another, even bigger tree on its way to the ground.

Mairi. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...