- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

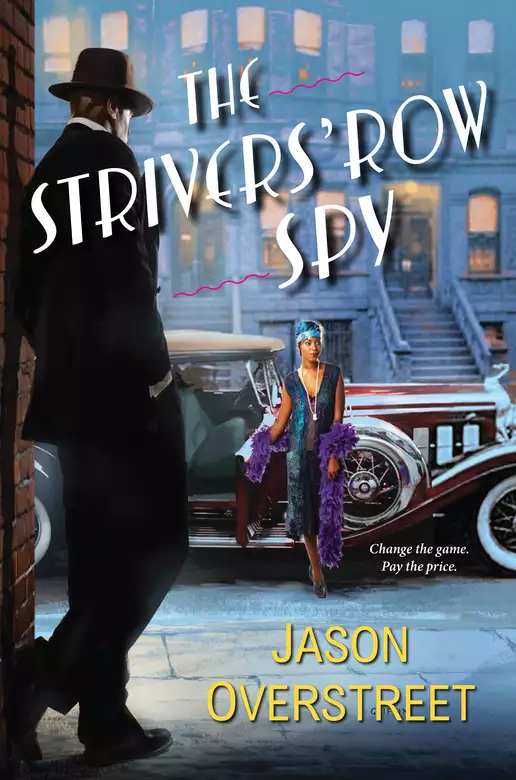

Synopsis

Stunning, suspenseful, and unforgettably evocative, Jason Overstreet's debut novel glitters with the vibrant dreams and dangerous promise of the 1920s Harlem Renaissance, as one man crosses the perilous lines between the law, loyalty, and deadly lies.

For college graduate Sidney Temple, the Roaring '20s bring opportunities even members of his accomplished black bourgeois family couldn't have imagined. His impulsive marriage to independent artist Loretta is a happiness he never thought he'd find. And when he's tapped by J. Edgar Hoover to be the FBI's first African American agent, he sees a once-in-a-lifetime chance to secure real justice.

Instead of providing evidence against Marcus Garvey, prominent head of the "dangerously radical" back-to-Africa movement, Sidney uses his unexpected knack for deception and undercover work to thwart the bureau's biased investigation. And by giving renowned leader W. E. B. Du Bois insider information, Sidney gambles on change that could mean a fair destiny for all Americans.

But the higher Sidney and Loretta climb in Harlem's most influential and glamorous circles, the more dangerous the stakes. An unexpected friendship and a wrenching personal tragedy threaten to shatter Loretta's innocent trust in her husband - and turn his double life into a fast-closing trap. For Sidney, ultimately squeezed between the bureau and one too many ruthless factions, the price of escape could be heartbreak and betrayal no amount of skill can help him survive.

Release date: September 1, 2016

Publisher: Kensington Books

Print pages: 448

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Strivers' Row Spy

Jason Overstreet

I glanced at my watch, then down at my shiny, black patent leather shoes. First time I’d worn them. Hadn’t ever felt anything so snug on my feet, so light. Momma had saved up for Lord knows how long and had given them to me as a graduation gift.

Again I looked up at him. He was a tall, thin man, dressed in the finest black suit I’d ever laid eyes on, too young, it appeared to me, to have such silver hair, an inch of which was left uncovered by his charcoal fedora. Even from a distance he looked like a heavy smoker, with skin the texture and color of tough, sun-baked leather. I had never seen any man exhibit such confidence—one who stood like he was in charge of the world.

I finally reached the top step and realized just how imposing he was, standing about six-five, a good three inches taller than I. His pensive eyes locked in on me and he extended a hand.

“Sidney Temple?” he asked, with a whispery-dry voice.

“Yes.”

“James Gladforth of the Bureau of Investigation.”

We shook hands as I tried to digest what I’d just heard. What kind of trouble was I in? Was there anything I might have done in the past to warrant my being investigated? I thought of Jimmy King, Vida Cole, Junior Smith—all childhood friends who, God knows, had broken their share of laws. But I had never been involved in any of it. The resolute certainty of my clean ways gave me calm as I adjusted my tassel and responded.

“Good to meet you, sir.”

“Congratulations on your big day,” he said.

“Thank you.”

“You all are fortunate the ceremony is this morning. Looks to be gettin’ hotter by the minute.” He looked up, squinting and surveying the clear sky.

I just stood there nodding my head in agreement.

He took off his hat, pulled a handkerchief from his jacket pocket, and wiped the sweat from his forehead. “You can relax,” he said. “You’re not in any trouble.” He put the handkerchief back in his pocket and replaced his hat. He stared at me, studying my face, perhaps trying to decide if my appearance matched that of the person he’d imagined.

He took out a tin from his jacket, opened it, and removed a cigarette. Patting his suit, searching for something, he finally removed a box of matches from his left pants pocket. He struck one of the sticks, lit the cigarette, and smoked quietly for a few seconds.

Proud parents and possibly siblings walked past en route to the ceremony. One young man, dressed in his pristine Army uniform, sat in a wheelchair pushed by a woman in a navy blue dress. He had very pale skin, red hair, and was missing his right leg. Mr. Gladforth looked directly at them as they approached.

“Ma’am,” he said, tipping his hat, “will you allow me a moment?”

“Certainly,” she said, coming to a stop. She had her grayish-blond hair in a bun, and her eyes were some of the saddest I’d ever seen.

“Where did you fight, young man?” asked Gladforth.

“Saw my last action in Champagne, France, sir. Part of the Fifteenth Field Artillery Regiment. Been back stateside for about two months, sir.”

“Your country will forever be indebted to you, son. That was a hell of a war effort by you men. On behalf of the United States government and President Wilson, I want to thank you for your service.”

“Thank you, sir.”

“Ma’am,” said Gladforth, tipping his hat again as the woman gave him a slight smile.

She resumed pushing the young man along, and Gladforth began smoking again—refocusing his attention on me.

“I don’t want to take away too much of your time, Sidney,” he went on, turning and exhaling the smoke away from us. “I just wanted to introduce myself and tell you personally that the Bureau has been going over the college records of soon-to-be graduates throughout the country.

“You should be pleased to know that you’re one of a handful of men that our new head of the General Intelligence Division, J. Edgar Hoover, would like to interview for a possible entry-level position. Your portfolio is outstanding.”

“Thank you,” I said, somewhat taken aback.

“I know it’s quite a bit to try to decide on at the moment, but this is a unique opportunity to say the least.”

“Indeed it is, sir.”

He handed me a card. “Listen, here’s my information. We’d like to set up an interview with you as soon as possible, hopefully within the month.”

He began smoking again as I read the card.

“Think about the interview, and when you make your mind up, telephone the number there. We’ll have a train ticket to Washington available for you within hours of your decision. Based on the sensitivity of the assignment you may potentially be asked to fulfill, you can tell no one about this interview.

“And, if you were to be hired, your status in any capacity would have to remain confidential. That includes your wife, family, and any friends or acquaintances. If you are uncomfortable with this request, please decline the interview because the conditions are nonnegotiable. Are you clear about what I’m telling you?”

“Yes, I think so.”

“It’s imperative that you understand these terms,” he stressed, throwing what was left of his cigarette on the ground and stepping on it, the sole of his dress shoe gritting against the concrete.

“I understand.”

“Then I look forward to your decision.”

“I’ll be in touch very soon, Mr. Gladforth. And thank you again, sir.”

We shook hands and he walked away. Wondering what I’d just agreed to, I headed on to the graduation ceremony.

I picked up my pace along the cobblestone walkway, thinking about all the literature and history I’d pored over for the past six years, seldom reading any of it without wishing I were there in some place long ago, doing something important and history-shaping. I may have been an engineer by training, but at heart, at very private heart, I was a political man.

I wondered, specifically, what the BOI wanted with a colored agent all of a sudden. I was certainly aware that during its short life, it had never hired one. Could I possibly be the first? I thought it intriguing but far-fetched.

“Don’t be late, Sidney,” said Mrs. Carlton, one of my mathematics professors, interrupting my reverie as she walked by. “You’ve been waiting a long time for this.”

“Yes, ma’am.” I smiled at her and began to walk a bit faster. I reminded myself that Gladforth hadn’t actually mentioned my becoming an agent. He’d only spoken of an interview and a possible low-level position.

“It’s just you and me, Sidney,” said Clifford Mayfield, running up and putting his hand on my shoulder, his grin bigger than ever.

“Yep,” I said, “just you and me,” referring to the fact that Clifford and I would be the only coloreds graduating that day.

“The way I see it,” he said, “this is just the beginning. Tomorrow I’m off to Boston for an interview with Thurman Insurance.”

Clifford continued talking about his plans for the future as we walked, but my mind was still on the Bureau. Working as an engineer was my goal, but maybe it could wait. Perhaps this Bureau position was a calling. Maybe if I could land a good government job and rise up through the ranks, I could bring about the social change I’d always dreamed of. I needed a few days to think it through.

Moments later I was sitting among my fellow classmates, each lost in his own thoughts inspired by President Tannenbaum. He stood at the podium in his fancy blue and gold academic gown, the hot sun beaming down on his white rim of hair and bald, sunburned top of his head.

“You are all now equipped to take full advantage of the many opportunities the world has to offer,” he asserted. “You have chosen to push beyond the four-year diploma and will soon be able to boast of possessing the coveted master’s degree. . . .”

Momma had told me from the time I was five, “You’re going to college someday, Sugar.” But throughout my early teens I’d noticed that no one around me was doing so. Still, I studied hard and got a scholarship to Middlebury College. My high school English teacher, Mrs. Bright, had gone to school here.

“It seems,” Tannenbaum continued, “like only yesterday that I was sitting there where all of you sit today, and I can tell you from my own experiences in the greater world that a Middlebury education is second to none. . . .”

I’d left Milwaukee, the Bronzeville section, in the fall of 1913 and headed here to Vermont. I had taken a major in mechanical engineering with the goal of obtaining a bachelor’s and then a master’s degree in civil engineering. I would be qualified both to assemble engines and construct buildings. Reading physics became all consuming, and I’d spent most of my time in the library, often slipping in some pleasure reading. Having access to a plethora of rich literature was new to me.

“I want you to hear me loud and clear,” President Tannenbaum went on. “This is your time to shine.”

As I looked across the crowd of graduate students and up into the stands, I saw Momma in her purple dress, brimming with joy. She was so proud, and rightfully so, having raised me all on her own. For eighteen years it had been just the two of us, Momma having happily spent those years scrubbing other families’ homes, cooking for and raising their children. But now that I had turned twenty-five, I would see to it that she wouldn’t have to do that anymore.

It was time for my row to stand. As we progressed slowly toward the stage, I became more and more painfully aware of my wife’s absence. I’d first laid eyes on Loretta in the library four years earlier when she’d arrived at Middlebury, making her the third female colored student here.

I’d approached her while she was studying, introducing myself and awkwardly asking her if she’d like to study together sometime. She’d just given me an odd look before I’d quickly changed my question, asking instead if she’d like to have an ice cream with me sometime in the cafeteria. She said yes and it was easy between us from that day on.

“Sidney Temple!” called out President Tannenbaum, the audience politely clapping for me as they had for the others. I walked onto the stage, took my diploma from his hand, and paused briefly for the customary photograph. I looked at Momma as she wiped the tears from her eyes.

I longed for Loretta to be sitting there too, witnessing my little moment in the spotlight. Before coming to Middlebury she’d spent one year at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and another at Oberlin College. But she’d finally found her collegiate home here and earned a degree in art history.

Her graduation, which had come three weeks prior to mine, had been a magical affair. Unfortunately, that celebratory atmosphere had come to an abrupt halt. Today she was grieving the loss of her father and was back home in Philadelphia arranging for his funeral. His illness had progressed during the last year, and he’d rarely been conscious the last time we’d visited him together. I figured that would be the last time I’d see him and had said my good-byes back then. Still, it was comforting to know that Loretta had insisted I stay here and allow Momma to see me graduate.

With the ceremony over and degree in hand, I headed to the reception the engineering department was having for a few of us. My mind raced to come up with a good reason for visiting Washington, D.C.—one that I could legitimately tell Momma about. As I arrived at the auditorium, she was waiting outside. We embraced.

“I’m so proud of you, Sugar.”

“I couldn’t have done it without you. I love you, Momma.”

The pending trip to Washington crept into my mind even during that long motherly hug.

A week later I was standing in the train station lobby in downtown Chicago on my way to the nation’s capital. I’d said my good-byes to Momma back in Milwaukee earlier that morning. My “good reason”? I’d told her I’d been asked to interview for a position on the Public Buildings Commission, a government committee established in 1916 to make suggestions regarding future development of federal agencies and offices. It was the first time I’d lied to her, and the guilt was heavy on me.

The Bureau had sent an automobile to pick me up at Momma’s place in Milwaukee and drive me to Chicago. It was a wondrous black vehicle—a 1919 Ford Model T.

When my train was announced, I headed to the car where all the colored passengers were sitting. Unlike the South, here in Chicago there were no Jim Crow cars I was required to sit in, but I guess most of us just felt comfortable sitting apart from the whites, and vice versa. Was the way things were in public. But it was a feeling I never wanted my future children to have.

All the folks on the train were immaculately dressed, and I felt comfortable in my cream-colored three-piece suit and brown newsboy cap. We gazed at one another with curiosity, each probably wondering, as I was, what special event was affording us the opportunity to travel such a distance in style. The car was paneled in walnut and furnished with large, upholstered chairs. It was the height of luxury.

I began studying the brand-new Broadway Limited railroad map I’d purchased. Ever since my first year of college, I’d been collecting every map I could get my hands on. It had become a hobby of sorts, running my finger along the various lines that connected one town to another, always discovering a new place various rails had begun servicing.

The train passed by West Virginian fields of pink rhododendron, then chugged through the state of Virginia as I reflected on its history and absorbed the landscape with virgin eyes. This was the land of Washington and Jefferson I was entering.

WASHINGTON, D.C., STRUCK ME AS A FANTASYLAND. AN AGENT PICKED me up from the station, and we made our way down Pennsylvania Avenue. Men in finely tailored suits with briefcases lined the streets.

As we drove by the Capitol Building, my heart began to race. It was everything I had imagined from an architectural standpoint. It symbolized power. For a brief moment, I imagined myself, the fresh engineer, building such a structure.

The closer we got to BOI headquarters, the more nervous I became. For the first time since meeting Gladforth, I began to have second thoughts about my interview. Why me? The magnitude of my being recruited by the Bureau hit me. Here I was, twenty-five years old and about to enter one of the most powerful buildings in the world.

The dull ache below my ribcage became a very uncomfortable twinge. The college nurse had chalked it up as stress. Clenching my jaw, I tried to shrug it off, fixing my eyes on the back of the agent’s blond head.

I waited in the lobby to be called into Mr. Hoover’s office. After what seemed a very long time, his secretary finally said he was ready. I entered the office and he stood from behind a desk, extending his hand without taking a step.

“J. Edgar Hoover,” he said, shaking my hand and sitting again.

“It’s a pleasure to meet you, Mr. Hoover. Sidney Temple.”

“Please, have a seat.”

Surprisingly, the man before me looked no older than twenty. He was about five-feet-ten with a boxer’s nose, thick, bushy eyebrows, and a squatty neck. He looked very much like a bulldog, but he was an exceptionally neat, well-groomed, and organized bulldog; I gave him that much.

I took a seat in an uninviting metal folding chair in front of his desk. As I scooted forward, the chair legs screeched against the marble floor. The entire office had an empty, cold feeling to it, with unpacked boxes and gray file cabinets lining the ivory walls, recently painted judging by the smell. He was obviously just moving in.

A framed diploma from George Washington University hung behind his desk, and various photographs covered the wall to his right. There was only one window in the office, designed, it seemed, to hinder rather than let in the sunlight.

“We’ve been doing a bit of shuffling between office buildings around here, Sidney,” he said, reading something. “I haven’t even been officially named head of the General Intelligence Division. That will happen on August first. But official titles aside, I’ve been given my orders.

“The attorney general’s office and those of us here at the Department of Justice have been told that these arbitrary locations are temporary—that we’ll be getting a permanent home base soon. I’m told they’ve been saying that for nine years. We shall see.”

I nodded while he stayed fixed on his report of some sort, flipping to another page.

“The BOI wants to make it a habit of tracking college students of all racial backgrounds who perform at the academic level at which you performed. We’re fond of those students, especially those”—his finger scanned the page—“with a knack for physics, mathematics, psychology, and law.”

He looked up from the file, seeing me for the first time it seemed, aside from the brief look he’d given before brusquely shaking my hand. “We’re even more enamored of those who remain apolitical,” he said, tapping the file. “In going over your history here, I find it remarkable, even a tad hard to believe, that you’ve never been a part of any fraternities, social groups, or committees—even during high school—not even on the student council. Correct?”

“That is true.”

“It’s one of the reasons you’re sitting in that chair. Your autonomy is appealing—that and the fact that you have the physique of a sportsman and not some bookwormy engineer. Have you ever been inclined to join any political party or national movement?”

“My focus from the time I left Bronzeville was on earning an engineering degree—nothing else.”

He looked back at the file. “I also see that two years ago you attempted to enlist for the war but were turned down due to a letter that was sent to the Army by your college president regarding your”—again his finger scanned—“unique acumen for physics, your overall distinguished scholarship.”

I was puzzled by that bit of information and responded, “I did attempt to enlist and was turned down. But I am unaware of any letter being written on my behalf.”

“That’s fine,” he said. “I know you weren’t aware of said letter. Your honest response is commendable.” He looked directly at me again. “Ever fired a pistol?”

To this question I wanted to lie and say yes and that I had done some training in hopes of preparing myself to be a soldier someday. I wanted to impress the young man but figured he was the type to suggest a visit to a shooting range to gauge my comfort level with a gun. He would have been sadly disappointed.

I also knew that he was probably suspicious, like most, of any colored who’d ever fired a gun. As far as I knew, there wasn’t a shooting range in America that allowed men like me onto their grounds. Therefore, any answer other than no would lead Mr. Hoover to believe that I had fired a pistol illegally. So I told the truth.

“Never,” I answered.

“Doesn’t mean you’re not a good aim.” Again, he looked at the file. “Your high school coach, a Mr. Sanders, says here your vision and hand-eye coordination is ‘unmatched on the basketball court.’ Based on the high marks and comments your coach gave you, I believe even Dr. James Naismith himself would be impressed.”

He looked back at me. “Anyway, the Bureau hasn’t been given the authority by Congress to allow its agents to even carry handguns. I’m hoping that will soon change, and when it does, I’m sure you’ll take kindly to a sidearm.”

“I believe I would.”

“I need to sign a few papers here, Sidney. Bear with me. But I’ll ask you while I’m signing. I want you to try to be as specific as possible with your answer. What do you know about the Negro scholar W. E. B. Du Bois—assuming you’re familiar with his philosophy? Are you aware of his communist leanings and dangerous agenda?”

I froze, trying to make sure I’d heard him correctly. “Well, I am . . .”

“Hold that thought,” he interrupted, as his focus was on signing the papers. “One minute.”

I was bothered by what he’d said about Du Bois and felt foolish all of a sudden. I had allowed excitement to get in the way of common sense. Gladforth hadn’t approached me to do the same type of work their other agents do. Of course not. They needed a Negro to spy on another Negro—one W. E. B. Du Bois.

“Just one more minute here, Sidney.”

I watched Mr. Hoover turn page after page, penning his signature on each. Little did he know he’d mentioned my idol. I’d read everything Du Bois had ever written. But I was certain that Hoover knew nothing about my views because I’d never written nor spoken publicly about the man.

I considered Du Bois the preeminent scholar of his time—the leader of colored America. And now, for that, the Bureau wanted to pry into his life. But they had the wrong man for this job. Besides, there would be nothing to find: He was completely honorable.

“All right, Sidney,” he said, returning to my interview, which seemed to be becoming almost a distraction from his real job. “Go ahead.”

“Well . . . I . . . I think that Du Bois’s precise objective is unknown.”

“Do you subscribe to the Crisis?”

“No.”

“Why not?”

Just then there was a knock and his secretary opened the door.

“Mr. Hoover,” she said, “Agent Lively needs you in the meeting next door for a brief moment.”

“I’ll be right there. Listen, Sidney, I want to apologize in advance for this, but I may be running in and out of here during our visit. I was to take part in another meeting next door but didn’t see why I couldn’t fit you in. Told them to call me in only when my opinion is needed. We all have to keep several balls in the air at the same time around here.”

“I understand.”

“Good.” He stood. “I’ll be back before you know it.”

Once he exited, leaving the door open behind him, I stood and walked over to the window, looked out, and tried to gather my thoughts. I actually read the Crisis religiously but hadn’t ever subscribed to it. Something Hoover didn’t know was how voracious a reader I was of many subjects, not just physics.

One of my more political teachers, Professor Gold, provided me with several colored newspapers, all of which were, of course, controversial. But he knew it was critical for me never to appear to be part of any movement if I was going to get hired at any institution as an engineer or professor. Whenever I took one of these newspapers home with me, he told me to “burn after reading,” and I always did.

“Mr. Temple,” said his secretary, walking just inside the doorway, “Mr. Hoover will be back in just a second. Can I get you anything?”

“No, ma’am. I’m fine. Thank you.”

She half smiled, walked out, and I turned back to the window, my thoughts still on Professor Gold. He and I were very close. He was a white man with socialist leanings. He had changed his name from Jackson, a name his father had adopted on entering the country, back to Gold upon his graduation from Harvard in 1872—likely out of pure embarrassment for bearing the seventh president’s last name.

Simply put, Professor Gold was like a modern-day abolitionist. He hated inequality and had taken a strong interest in me my freshman year. He told me I was brilliant, took me under his wing, mentored me, damn near treated me like a son. I think he believed that helping me was like helping an entire people.

When I married Loretta, we moved from our dorm rooms into a tiny guesthouse on his ten-acre property, situated in the woods about five miles from the college. The grounds were nestled in between acres and acres of sugar maple trees. We would walk over to his chalet on most weekends, as our guesthouse was on the opposite end of the property.

It was at his place that I read and discussed politics with him for hours on end, while Mary, his wife, would work on her essays and Loretta would paint in the little bedroom they had converted into a studio just for her.

I knew Professor Gold would never tell a soul about me, including any Bureau agent who may have come around. Gold was concerned about hiding his own political activity, so he never would have said a word. Luckily for him, the Bureau had no interest in him or his activities—just mine.

“Okay,” Mr. Hoover said on his return, closing the door behind him. “Where were we?”

“You wanted to know why I hadn’t subscribed to the Crisis.”

“That’s right.” He sat down. “Why not?”

I moved from the window back to my chair. “Well, I’ve never subscribed to it because . . . probably . . . or . . . let me rephrase that . . . precisely because during my twenty-five-year lifetime, I’ve never been given a reason to believe I wasn’t the equal of any man, regardless of race.

“Perhaps my mother left Chicago with me when I was five because she wanted to, in some way, shelter me from reality. The Bronzeville streets, though they contain some rough elements, are not as brutal as those in Chicago. Truthfully, I have accomplished every goal I’ve ever set. My life has not been a crisis—no pun intended, Mr. Hoover.”

“Does your own success desensitize you to the struggles of the greater Negro race, assuming you believe that there is a struggle?”

“No.”

“In twenty words or less, define what America means to you.”

“It means unparalleled courage, sacrificed blood, broken chains, and the relentless hope of a united people.”

Hoover sat there for a moment and stared at me. I couldn’t tell if his glare represented a newfound hate for me, a respect for my opinion, or a surprised reaction to the quickness with which I’d responded to his question.

His poker face was impressive. My bold answer about racial equality was likely a death sentence for this potential career, as I had no idea what theories on race Mr. Hoover might have, but at this point I didn’t really care.

As he continued his stare, the desk phone began to ring. “That’s likely the attorney general,” he said. “There isn’t enough time in the day. One minute, Sidney.”

He picked up and it occurred to me just how ignorant I was being. If they wanted to spy on Du Bois, there was no stopping them. And if I turned the assignment down, if indeed that was what my role was to be, there would be some other colored graduate willing to infiltrate Du Bois’s world—someone lacking my loyalty and respect for the scholar—someone willing to destroy him for the right amount of money.

“No, Mr. Palmer,” he said into the phone, “that entire outfit has been turned over to Kirkland. But I can put it back in the hands of Fennison if you feel that Kirkland could be better utilized in Santa Fe.”

Having heard Hoover call Du Bois “dangerous” felt like a call to arms. I could, especially as a covert agent, protect him and his integration agenda from his enemies, including the government. Du Bois surviving would ensure a better America for my unborn children. And if protecting him meant I needed to get inside the beast—the impenetrable beast that had played a role throughout American history in influencing the destiny of our nation—I needed to do it. This relatively new Bureau was part of the innards of that beast.

“You have my word on it, sir,” continued Hoover.

I began to envision the potential spy mission as a sacrifice for Du Bois that only someone with my unique pedigree, intelligence, and beliefs would be able to make. I was also confident that I could outsmart this Mr. Hoover, especially considering we were roughly the same age. Perhaps my biggest flaw was that I’d always believed I could outsmart everyone around me.

He hung up the telephone. “Sidney, the Bureau has never hired a colored agent. Earlier today I interviewed a man by the name of James Wormley Jones, a soldier. Was stationed in France. I may hire him. Do you have any clue as to why I would even consider hiring him as the first-ever colored agent since the inception of our Bureau?”

“No.”

“Loyalty.”

“I see.”

“The Bureau of Investigation wants men who care about what’s in the best interest of America first. Jones obviously understands this—he was willing to die in a war. And I am quite certain that you, in your eagerness to enlist back in 1917, were willing to die as well. I can only imagine the pride these men must feel today as each returns to a hero’s welcome across the country. I didn’t fight in the war. I was already employed at the Justice Department at a very young age and was exempt from the draft. I regret that.

“Fighting in a war,” he continued, “and surviving it, allows a man to brush aside the kinds of regrets a typical man becomes entangled in throughout life—regrets about trivial failures and whatnot. A willingness to die for this nation is the ultimate badge of honor. And I’ve examined the details of your life enough to believe that you possess such a badge.”

“Thank you, Mr. Hoover.”

He began jotting something down. The man had mentioned my willingness to die, and he was right. I’d do so for Du Bois. And had I gone off to war, I certainly would have made a good soldier. I would have tried to

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...