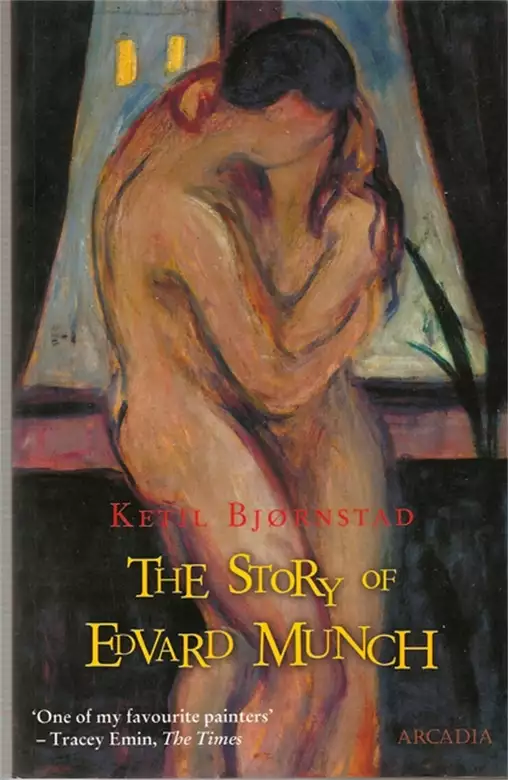

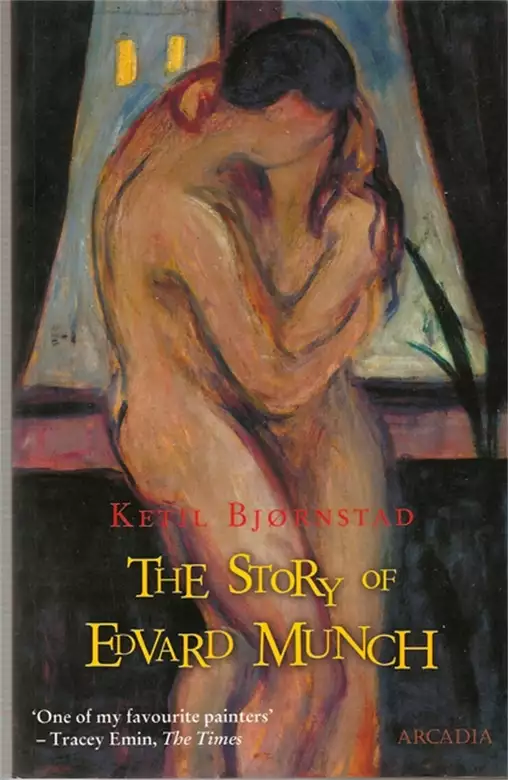

The Story of Edvard Munch

- eBook

- Paperback

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

A fascinating literary construction of the life of one of the world's most popular 19th century painters which is based on Munch's own diaries, notes and letters. His troubled relationships, particularly with the opposite sex, are well documented as is his nervous disposition which complicated his entire existence and these aspects of his life are admirably brought alive by the author. Illustrated.

Release date: June 10, 2013

Publisher: Quercus Publishing

Print pages: 416

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Story of Edvard Munch

Ketil Bjornstad

‘Invaluable for anyone interested in the great Norwegian painter. Drawing heavily from Munch’s extraordinary writing, most of which is unpublished, Bjørnstad gives the reader a lively and intimate account of an artist whose love and suffering became his work’ – Siri Hustvedt

‘This is a wonderfully vivid recreation of Munch’s life. It lets us enter his world far more intensely than a conventional biography … building into a dazzling tapestry which has the weight and inevitability of myth’ – Ned Denny, Daily Mail

‘Meticulous research is presented with all the lyricism of a modernist musical style … Bjørnstad’s poetic prose has authority and beauty’ – Lesley McDowell, Independent on Sunday

‘The forces behind Munch’s nerve-jangled, corrosive 1890s works are brilliantly evoked in the jump-cut, freeze-frame technique … it impels re-examination of the work, in itself an excellent result’ – James Malpas/Sotheby’s Institute, The Art Newspaper

‘Nothing I have read about Munch before has made me feel so urgently, so almostly uncomfortably close to the great artist’ – Gothenburg Post

‘A captivating portrayal of a young man’s obsession and love’ – Lars Saabye Christensen, author of The Half Brother, on Bjørnstad’s novel To the Music

‘Highly praised’ – Irish Times

‘Enthralling. Bjørnstad succeeds in making immediate not only a life but also an epoch’ – Suddeutsche Zeitung

‘A primer to Munch’s work … through this inventive account we can feel the darkness at the break of noon, as Bob Dylan once wrote’ – Graham Reid, Weekend Herald

‘A great achievement, written with the finest, most etching needle – it trembles from Munch’s nerves’ – Weekendavisen

‘A beautifully written, intensely crafted book … the character of Munch lives and engages the reader’ – Historical Novels Review

‘Splendid about Edvard Munch … enriches our relationship to Munch and his art, to art as such and to life – if you don’t lose yourself in the reading then you are missing out’ – VG

‘Fascinating’ – Anglo-Norsk Review

‘A vastly intriguing portrait of a man now universally regarded as a great painter’ – Joan Tate

Dying I came into the world.

(EDVARD MUNCH)

Dear Thiis: It’s been five years now. I’m still just as hurt and just as devastated. That creature who hadn’t the least desire to remain tied to mama’s apron strings, but who, after a fairy tale life full of travel, had decided to marry me, propelled me through the very doors of hell. She travelled the length and breadth of Europe and started a string of affairs, blackened my name among all my friends, drove me half-mad with scenes until, in 1902, there I was, a wreck for life. As for her, she calmly and serenely entered into holy matrimony, famous, admired and worshipped, a goddess of art, and far, far away from mama. I am a wreck. I who became entangled with her after she had thrown two uproarious champagne parties. I who did not love her, but who out of sympathy sacrificed everything I had. I am not, like Christian Krohg, obliged to marry a whorehouse or, like him – like the gritty, bloody-horned snail that he is – to carry that whorehouse on my back. I have felt myself compelled to write this on seeing Gunnar Heiberg shed tears from his witty little eyes in Dagbladet over that painter who wore himself out and went mad. Is it any wonder that my hackles rise when I see his name? It was not hunger that drove me from Norway but that rotten little bunch of friends who stabbed me in the back. The meanest of all mean tricks: to cry Help! Help! I’m drowning! And then, with a contemptuous snort, to let your rescuer drown.

*

Edvard Munch on the brink of the abyss, just before his breakdown. Wine, brandy and the strongest cigars. Drunken stupor.

All his life he had known of the abyss. In 1908 he plunged into it, was admitted to Doctor Jacobsen’s psychiatric clinic in Copenhagen. In 1909 he returned to Norway, after four years’ exile.

*

There is a time in everyone’s life when everything comes sharply into focus, both what has already been and what the future can reasonably be expected to hold. In Munch’s life this moment must have been when, at the age of forty-five, after his breakdown, he arrived in Kragerø, not from the east via Christiania, as I first thought, but from the west, via Kristiansand. Not early in the morning, when the spring sun floods in over the rugged archipelago which in the month of May is no longer pale and battered after the winter, but in the middle of the day, at about twelve o’clock, long after sunrise, in an almost neutral grey revealing light.

The coastal steamer coming from the west did not sail past Jomfruland, as I had thought, but swung into the fjord at Rapen. Munch may nevertheless have seen both Jomfruland lighthouse and two other light buoys on the way in. A boat the size of the coastal steamer could not sail on the landward side of Jomfruland if it came from the west. Nor from the boat could Munch have seen both thrift and blue-bells, as I had thought, because the boat was too far out on account of the skerries, and apart from that because bluebells flower long after thrift does. But at Skrubben, the house in which he was to live while in Kragerø, he would soon see them, as spring turned into summer.

*

Ravensberg! Noble kinsman! Have you not heard the howls from the enemy camp? Have my grenades had any effect? I think that the scoundrels CK, GH and SB have thrown in the sponge at last. It’s good to have an outlet for your feelings when you cannot simply beat riff-raff of that ilk to a pulp with your bare hands. You can bet SB heard a few home truths in 10 postcards I sent. I shall tell you later how the Enemy was already at work, poisoning wine in Cologne and stealing the large rolls of paintings. They have spread influenza here and killed my castle guard. I grope my way forward in the narrow passage. My fingers come into contact with a crate. I continue. Cloth. I pause. A terrible stench. I continue. Hair. Nose. A human being. A corpse!

*

It was Munch’s cousin, Ludvig Ravensberg, who collected him from the psychiatric clinic. The night before he was admitted he had limped all the way from Klampenborg, his lame leg dragging behind him. His hair unkempt, his clothes in tatters. He was turned away from a restaurant. In the end he had taken a room at a hotel in Copenhagen, convinced he was surrounded by enemies. Norwegian enemies. Two hotel rooms. One with a window overlooking the courtyard and one with a window onto the road. He had heard voices. They had said his name:

There he is! Watch him!

He had dragged himself to the window but had seen nothing. He felt numbness spreading through his body. He had not had a proper night’s sleep for many weeks. His wounded hand ached.

It was Ravensberg who took him away from all the postcards, from the animal drawings, from rages and humiliation, brought him back to the land of his enemies. Why on earth had he come back to Norway, that vipers’ nest, to people who had assumed the form of frogs, pigs and poodles? The strangest specimens in the menagerie, which he referred to as this crafty, insolent, decrepit circle, a clique of clapped-out literati, drunken offspring of the rich, whorish women and people who had never had an independent or original thought in their heads, but who spent all their time, expended all their energy, copying, faking, impoverishing, draining sap from the few sparse trees which managed to gain a foothold and had some life in them, people whose names he still could not mention without getting agitated, feeling dizzy, names that previously he had not been able to hear without feeling physically sick and persecuted.

Up on the deck of the steamer, he must have thought along these lines, must have thought that this journey might be a disaster, that Ravensberg had actually misled him, given him to believe that it was a long way from Kragerø to Christiania, even though it was barely two hundred kilometres. And that terrible doubt must have made him waver, not because the sea was rough, because in all probability the weather was good, but because the thought of disintegrating like this induced just as great a fear of death in him as when he had coughed up blood as a child.

*

It was then that he saw in his mind’s eye the middle-aged man, racked by many years’ hell, destroyed by alcohol, fear and rage, his head so full of pictures from memory, of colours and contrasts, yet all the same back on his feet, shaky but back on his feet, with a vast yearning for control, and at the same time a deep-seated doubt as to whether such control could ever be attained. Yet nevertheless firmly resolved to try, at least so long as Ravensberg cheered him up, patted him on the shoulder or whatever it was he did, while the captain sounded a blast on the hooter, while the crowd of onlookers on the quay scrutinized the queue of passengers waiting to go ashore, while Ravensberg yet again glanced searchingly at his friend, as if to register the minutest change in the closed face which, despite the firm masculine set of the chin, always expressed such boundless vulnerability, and the steamer at last docked at the quay.

The journey by steamer must have done him good after all the weeks in hospital. The smell of mental breakdown had had a stronger effect than the smell of physical ailments and medical preparations. An indeterminate odour of physical decay and desperate thoughts.

Fresh air!

How deeply Munch must have filled his lungs with the sea air, undeterred by the stench of Norway.

*

He was in the process of turning a scandal into a success. He had received the Order of St Olav, which he ventured to construe as a friendly gesture from his own country, even though he declared himself an opponent of decorations and the death penalty.

*

What was it about this country which drew him back? He had used a few square miles of it to create his art. The strip of coast between Borre and Åsgårdstrand, a little town on the western side of the Christiania Fjord. Christiania’s main street, Karl Johan. The flaming red sky over Ekeberg. And also the childhood sketches of the church steeple, Telthusbakken, the river Aker. The deserted, almost trancelike atmosphere around Olav Ryes Place, perhaps slightly contributing to the agoraphobia, the dread of open spaces, of which he would later offer such a perfect hysterical example.

But above all it was Åsgårdstrand. That had been the scene of the drama, of the revolver, the Medusa’s heads, the broken lover. Perhaps there too the explanation was to be found for all the harrowing events which would subsequently unfold.

In short, the scenes of his past.

He wished to return to his past, to the scenes of everything that mattered to him: his pictures. But he had no desire to relive it! Not The Frieze of Life Act II. That was over now. The actors had found their roles. Men and women alike. Now they had acquired their forms, colour and expressions.

*

He sees again all that is Norway, all he has painted time and time again in constantly new versions since the drama played itself out. He has painted white wooden houses, massive trees, a shoreline, some islands, the sea. He is coming to Kragerø because he had been looking for a peaceful spot by the open sea. Ravensberg found it. Good news: there is a house by the sea. Bad news: the house is in Norway. Yet it is not so much Norway Munch is against as Christiania. The city he grew up in. The city where he is always judged, weighed and found wanting. The city where the Enemy is.

*

Once blood had dripped from the hand wounded by the shot.

Munch cannot forget.

Cliffs and rocky outcrops tower menacingly before him. Does he still have any feeling in the last joint on the middle finger of his left hand? The one that is no longer there? What has become of it? Is it in a glass jar, has it turned to ashes or to earth while the rest of his body is living tissue and ageing cells?

He gazes expectantly at the onlookers on the quay, perhaps thinking of the old pictures of the enemy. But what drove him out of the country was a woman.

*

He walks down the gangway in Kragerø’s harbour. Has chosen to step on Norwegian soil. His soil. But not his town. Not even a typical Norwegian town, but a sort of Italian amphitheatre with narrow streets. It does not have all that many large squares, which he would in any case refuse to cross, but up the steep slope it does have a spacious house with a garden.

Peter Bredsdorf’s house. Skrubben, or the bath house. It is empty and to let.

Perhaps he can wash himself clean of the past. Of everything that has happened. Yes, perhaps.

But not of the pictures.

*

They rise up from the bottom of the sea.

The sea bed is like his own memory. He has likened life to a still surface on which one can shift one’s gaze from shallow to shallow, from deep to deep. Again and again he has brought up pictures from there himself. He knows the best places to fish. In some places there is always life. In other places there is only death, putrefaction and slime.

Somewhere in there lies Åsgårdstrand.

Somewhere out there the assembly hall sun will soon rise.

It is May 1909 and he will later confide to his friend Schiefler in Germany that his agoraphobia is considerable, very pronounced, perhaps more acute than when he used to drink. The thought of large cities is intolerable now.

Berlin? Paris? Impossible. Even Christiania must seem frightening. Karl Johan. The promenade between Parliament and the Palace. Where he would walk with Hans Jæger and learned how the middle classes can see, with just one eye! Oh no, Ravensberg was right. Kragerø is perfect, provided he can avoid the market place.

*

Munch enters a spacious house with linoleum on the floors. It is barren and impersonal, just as he wants it. No furniture, no melancholy air of homeliness which in any case can never be anything but an illusion of happiness in life.

Here is his life, his body. In a large empty house in Kragerø, with council furniture. He will become a night wanderer. A ghost. A button moulder has recast him.

But is there any substance to the material? Is it fit for anything?

He has felt close to death so many times. Weakness of the lungs. Insanity. In Copenhagen he was mad, half-paralysed and shaking with fear. Now it is ‘Power’ and ‘Strength’ – his domestic helps Krafft and Stærk – mountains, shandy, nourishing food, which are the order of the day. Farewell to whisky and soda and cigars, to burgundy and vintage champagne. His senses are sharpened. He hears all sounds at double volume. Sense impressions can almost knock him flat with their force. He thinks he can see the flame of combustion around people’s silhouettes.

This is where he wants to live. This is where he can regain his strength.

Here he remembers everything.

* * *

Munch walks through the city from Grünerløkken.

The commuter ferry or ‘papa boat’, carrying all the fathers, will steam out along the fjord to all the idyllic little towns and villages, where wives, children and families are waiting.

The air is warm and close down by the jetties.

He boards the little steamer, finds a seat on deck, longs to get out onto the fjord. It is June 1885. Christiania lies there all dust and stench. The sun is baking hot. There is an audible stillness, as though before an explosion, punctuated by hammering from a workshop and the bell of a departing steamer.

Munch sits up on deck sweating. He observes everyone who comes on board. He recognizes a married couple. The Thaulows. Not the painter Frits, who helped him with his scholarship, but his brother and sister-in-law.

Munch has met him before. He is a captain in the naval medical corps, Carl Thaulow, a distant relation. He is a very imposing figure. The lady-killer of Karl Johan they call him. While she is one of those people who are talked about, the daughter of an admiral. Scandalous tales, unfaithful to her husband. Is there any truth in it? Yes, she looks rather self-assured.

The captain has accompanied her to the ferry.

Now she is saying goodbye to him.

The bell rings for the last time.

Then they glide out over the shimmering silver water.

*

She takes a seat opposite him.

She has a lovely neck.

He also notices her shoulders.

The steamer is crowded, ladies in pale blue, pink and white summer dresses, plump wealthy citizens, with port-wine-red faces, weighed down with holdalls and parcels. Students and lieutenants, wholesale merchants puffing and panting in the heat and looking as though they might succumb to apoplexy.

He is sitting directly opposite a married woman with a reputation. Now she greets him. He returns the compliment. Then they sit avoiding each other’s eyes. He looks at her in the June sunshine, registers her features. She has large lips. Strange then that everyone should fall in love with her. Odd that she should have tired of the handsome and imposing lady-killer of Karl Johan.

Munch waits for something to happen. He is surrounded by love, the scandal with Christian Krohg and fru Engelhart, previously frøken Oda Lasson, the Attorney General’s daughter. She has apparently forsaken husband and children for a radical painter. Rumours are rife.

Munch leans back in his chair on deck. They say she’s taken another painter as lover recently. Munch knows him. He’s not all that much older than himself. Might Munch have a chance? He has been to museums abroad, seen naked women in glistening oils. He draws naked models here in Christiania. As a painter, he is already old in his assessment of women. He is not easily impressed.

Now he looks at fru Thaulow. He sees that her mouth is ugly. Her lips are too large. Her skin is too coarse.

The steamer ploughs its way through the waves.

He engraves her on his mind, etches her firmly into his memory. He surreptitiously adjusts his collar, lights a cigarette, blows the smoke slowly up into the air, knows that his Parisian clothes fit him well.

He wonders whether he should address her by saying: Good day, madam. No, that wouldn’t be right. Instead, perhaps: Madam, you probably won’t recall? No, that’s no good either. He can’t pluck up the courage, all he can do is steal furtive glances. Every time she looks at him, he hastily averts his eyes.

Then she takes out a purse, buys some cherries, offers him a handful.

Thank you. Thank you so much. Are you going far?

Yes, to Tønsberg.

Well, well, same here!

How nice. Where are you going exactly?

To Borre, near Goplen.

To Borre? Really? Even better, so we live right next to one another!

Munch suddenly finds her very pretty in her thin pale blue costume, thinks she’s amusing when the wind blows her thin dress up and she bends forward to cover her legs. She turns to him and smiles. There he sits in his Parisian clothes holding his stick and tries to smile back.

*

In the harbour at Tønsberg stand the military doctor with Aunt Karen, Andreas and his sisters. Munch waves to them. Can they tell from his appearance that he has been abroad? He is a painter now. An artist. Has been in Antwerp and Paris. Has bought new clothes.

Munch walks down the gangway. He loses sight of fru Thaulow in the crowd. His family come towards him. He has come back to what is familiar, to Aunt Karen’s gentle solicitude, the military doctor’s inquiring look.

They walk along the fjord up towards Åsgårdstrand and Borre.

Munch tells them about all he has seen in the great wide world.

* * *

She comes towards him in a coach.

His immediate thought is that he is wearing his worst pair of trousers, the ones he is going to use in the country this summer until they wear out. His tie is crooked.

He freezes. There is nowhere to hide.

Now she is suddenly right in front of him.

The coach has stopped.

Smiling, she leans down towards him, gives him her hand.

There he stands on the country road, between the red and yellow houses with small gardens in front, feels a soft warm female hand. She laughs with white teeth, peering at him:

Your hair’s wet. Have you just got up?

He is tongue-tied. The coach she is sitting in is full of flowers. Large yellow flowers.

What a charmer you are, she says.

She picks up a flower and hands it to him.

There you are. It’s for you.

He still does not speak. She takes another flower.

And this is for your other hand.

There he stands, a yellow flower in each hand, looking at her.

Will you come and visit me tomorrow? she asks.

Yes, thank you, he replies.

*

He returns home to the family, hides the flowers in a crate in the attic so no one can see them. But his sister Inger has seen him.

Wasn’t that fru Thaulow you were talking to?

Yes it was, he replies casually, blushing.

The military doctor glances up from the armchair. Fru Thaulow? She looks so sad these days.

Yes, says Aunt Karen. People say she’s not very nice to her husband.

People say all kinds of things.

True.

It is summer. The Munch family are sitting at the dining table. The sound of knives and forks. Aunt Karen coughs. It is a bright evening. The water is light blue and violet. Munch notes the delicate hills and the shimmering air. Deeper and deeper violet. Up there above the tops of the fir trees – the moon small and pale as a silver farthing.

After the meal they walk out into the garden. His father has his pipe in the corner of his mouth. He is sitting on the bench, has put on his dressing gown, peers over the top of his glasses. Laura, wearing a white dress, is tending the flowers. Inger and Aunt Karen are knitting. Andreas is reading a book.

What a lovely moment. How fortunate we are, says the military doctor.

*

The next evening it is raining.

Heavy clouds chase across the sky in huge unbroken masses. The wind is blowing from the sea. The church shines white in the evening light surrounded by the graves.

Munch is approaching the russet-coloured house on the other side of the road.

She is standing on the veranda in a white hat like a jester’s cap. She has placed it at such a coquettish angle. It doesn’t suit her. He meets her gaze. They go into the house.

The Ihlen family’s house. The admiral’s home. It is evening. Now she doesn’t look so young.

They go into the dark room. Huge heavy banks of cloud outside. She had just been standing on the veranda. Now she is in the house. He is with her. The jester’s hat does not suit her. Her fringe tumbles down over her eyes.

She looks like a tart, he thinks.

Shall I show you my precious things, she asks.

*

She shows him the house.

That painting is divine, good colouring. She screws up her eyes and looks at it as painters do. Divine. The view from here is divine too. Look at the sea down there. Just like the first yellow flower she gave him. Divine. Look at the colours above the hills over there. Divine.

I know what I’m talking about, she says, I’ve spent a lot of time with painters.

Her reputation! Who was it who had whispered to him about that other painter, her lover?

At that moment he happens to glance down at some papers lying on the table. She snatches them away.

A letter, she says. She looks him straight in the eye. Says she is writing to him. Says it without batting an eyelid.

Perhaps she’s not aware of the rumours.

I’ve known him since I was a child, she says. I’ve always been very fond of him. But I so easily tire of people.

Isn’t he a bit of a bully, asks Munch cautiously.

She looks out of the window, her stomach pressed against the edge of the table, both hands tucked into the belt around her waist. Her arms are round, half-bare. The red bodice is very décolleté.

Munch observes the full bare throat. Her hair is combed up from the neck. As yellow as ripe corn. Now she is close to him. He is accustomed to observing, doesn’t really like her mouth, it is so broad and pouting. Her nose is too large. Cleopatra must have looked like this.

That’s a beautiful belt you’re wearing, he says.

She stretches the belt down over her stomach and shows him the clasp.

It must be old, he says, stooping to take a closer look.

He feels her arm close to his cheek.

Yes, it is old, she says.

*

She lights the fire. They sit by the hearth. The flames cast their glow into the room. She sits reclining in the chair.

You should be called something else, she says.

D’you think so?

Yes, I do. Something or other. Like in those French novels.

Outside the lamp has been lit, the sea is visible through the door into the garden. The fire crackles. Then he hears footsteps in the corridor. A young woman comes into the room.

*

Supper. Supper with meat. Here’s a nice piece. Now there is meat on Munch’s plate. Thank you very much. He is not hungry. There is a sort of lump in his throat. Do eat, please. Fru Thaulow and frøken Lytzow. So frøken Lytzow is getting married. When? Tomorrow? Really? My word. Congratulations. Yes, on the contrary, I am very hungry. Meat. It’s very good meat.

He feels how hot he is. A heat wave. Must say something, talk, come up with something. The silence makes him much too nervous. Words suddenly come tumbling out of his mouth. False-sounding words. Colliding with the silence in the room. That blue landscape out there is really beautiful, he says. It reminds one of Puvis de Chavannes.

Munch tries to eat the piece of meat, the sweat begins to trickle out of his pores and the food sticks in his gullet. But you’re not eating? Yes I am. Are you not particularly hungry? My goodness yes. Very. Munch feels himself blushing. Then he’d gone and mentioned Puvis de Chavannes, thinks Munch, the creator of Pro Patria Ludus, four metres high and sixteen-and-a-half metres wide, as it hung at the World Exhibition in Antwerp. Why on earth had he said it? How dreadfully pretentious the words sounded. How boring they must find him. The blue landscape. Chavannes. Perhaps he is pronouncing the name wrong. Perhaps both women speak very good French. Fru Thaulow at any rate. In a few years’ time she will be travelling the length and breadth of France singing chansons. Dreadfully pretentious. And his mouth is full of meat.

Fru Thaulow glances at her friend. Is that a little smile he catches? My goodness yes. Fru Thaulow is smiling at frøken Lytzow. Now frøken Lytzow is smiling too. So this, says frøken Lytzow, is a tender new shoot you’ve unearthed?

A budding artist, says Munch.

Good heavens, what was that he said?

It just popped out of him.

Ridiculous.

He is deeply embarrassed. Is it too late to make it seem like a joke? He tries to put on a jokey air. Fru Thaulow’s friend then also starts to laugh, either out of duty or to divert attention.

How lovely, she says. Two artistic souls. A meeting of great minds. How very fitting.

Then Munch has to steal a look at fru Thaulow. She looks dreadfully serious. It’s quite obvious she’s trying not to laugh. She is sitting stock still. Terribly serious. Her face is becoming red with the effort. Dreadfully serious.

*

The laughter explodes. Not ordinary laughter, but a gale of laughter. Laughter which stops suddenly only to start off again, even more uncontrollably. Fru Thaulow has to put down knife and fork. Munch notices that she is hugging her sides with both hands. Now she laughs, her wide mouth open. Munch looks at her face. The lamp and the plates start to spin before him. He feels wretched. Utterly wretched. What can he do? He is sitting at fru Thaulow’s table grinning idiotically. Suddenly she can’t hold it any longer, gets up abruptly, goes into a corner, crouches down. She laughs so hard she cannot breathe and gasps:

Oh, it’s too much, just too much!

He sits at the table looking at her.

Suddenly all grows quiet.

Frøken Lytzow looks at her friend in alarm.

I think you’re mad, you’ve completely taken leave of your senses.

Fru Thaulow slowly gets up, says that she just couldn’t help it.

Munch gets up from the table and goes over to the window.

He places his forehead against the window pane to cool down.

*

Later he writes: Kirkegaard lived in Faust’s time. Don Juan–Mozart–Don Juan. The man who seduces the innocent girl. I have lived during the transitional period. In the midst of the emancipation of women. Then it is the women who seduce, entice and deceive the men. Carmen’s time. During the transition man became the weaker of the two. Don Juan Mozart – Carmen Bizet.

*

He hates her.

A blind, desperate hatred. Red blood courses through his veins. Steaming human blood. The pulse of life beats in every fibre beneath his skin. Is this life? Is this what it feels like? The enormity of his humili

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...