- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

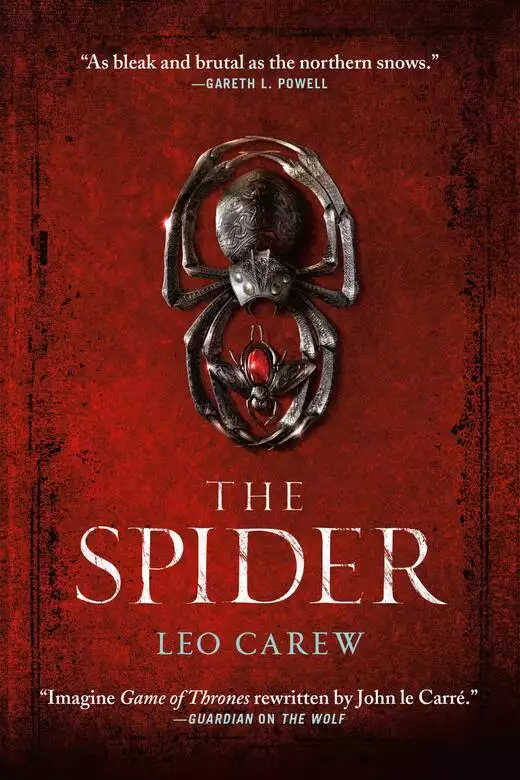

After the critically acclaimed epic fantasy THE WOLF comes THE SPIDER, book two in Leo Carew's UNDER THE NORTHERN SKY series

A battle has been won, but the war still wages on . . .

Roper, the Black Lord of the northern people, may have vanquished the Suthern army at the Battle of Harstathur. But the greatest threat to his people lies in the hands of more shadowy forces.

In the south, the disgraced Bellamus bides his time. Learning that the young Lord Roper is planning to invade the southern lands, Bellamus conspires with his Queen to unleash a weapon so deadly it could wipe out Roper's people altogether.

And at a time when Roper needs his friends more than ever, treachery from within puts the lives of those he loves in mortal danger . . .

(P)2019 Headline Publishing Group Ltd

Release date: July 30, 2019

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 544

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Spider

Leo Carew

“I still don’t know the plan,” said the oarsman.

The darkness clotted at the stern made no reply. It just hoisted a hood against the rain, and stared out over the pitch sea.

“You could take an oar,” said the oarsman, whose name was Unndor. “We’d be faster.”

The shadow flicked a hand towards his own enveloped arm, held in close and vulnerable at his chest. “We would not.”

The boat was drawing towards a bright pinprick, far across the water. The waves knocked on the hull, rocking the pair as the distant light slowly resolved into a ship, twinkling silently as dark figures crossed the deck. It grew huge: a rolling, sweating, round-bellied hog of a ship without porthole or mast, fastened to the sea floor by two hemp ropes running beneath the waves. The top was awash with yellow lamplight, obscured as the little boat passed into the shadow of the hull. They had been spotted, and a silhouetted head protruded over the side. “Ellengaest, is that you?”

“It’s me,” replied the shadow from the stern.

The head retreated at once. “They were expecting you?” asked Unndor.

“I am their only visitor who arrives at night.”

A rope was tossed over the side, a pair of hands appearing above to lash one end onto the rail. Unndor took the rope and knotted it onto an iron ring at the bow, and then a rope ladder tumbled down the hull, its end coming to rest just above the boat’s knocking gunwale. The passenger, the Ellengaest, did not move, and after a moment, Unndor took the ladder and began to climb. When several hands had reached from the ship to help him over the rail above, Ellengaest followed.

He was pulled aboard a solid acre of planking, bordered by a low rail, and gently curved like a fragment of an enormous barrel. The deck bristled with posts, each bearing a pair of blackened storm lamps, and the whole vessel gleamed with tar and rain. The men on the deck wore beaten expressions and heavy black cloaks, each emitting the smoky reek of tar, rain beading on the stifling garments and drifting through the lamplight. The captain, Galti, was small and hunched, and stood a half-pace further back from the towering form of Ellengaest than might have been normal. “What can I do for you, sir? Leave us,” he added to the deckhands.

Ellengaest watched them go. “This place is hell,” he said.

Galti did not disagree, staring up at his visitor, the rain running down his face.

“We have come to see one of your prisoners, Captain,” said Ellengaest. “Urthr Uvorenson.”

Galti’s foot twisted beneath him. “What do you want with him, sir? I ask as he is quite a high-profile prisoner.”

“Not your concern, Captain. Lead on.”

Galti hesitated, gritting his teeth, and then turned away, leading them to a hatch at the heart of the deck. He pulled it open to unleash an abominable stench: damp, excrement, rot and urine in one potent gust. Unndor staggered back, but Galti swung himself down onto the rungs of a hidden ladder and disappeared into the cavity. The two new arrivals paused by the entrance.

“Ellengaest?” asked Unndor. “Why Ellengaest? Sounds like a Suthern word.”

“You next,” said Ellengaest, without looking at Unndor.

“My brother has been living down there for three months?”

“Go and ask him yourself.”

Unndor screwed up his face and plunged in, having to twist slightly to accommodate his shoulders. Ellengaest delayed long enough only to take a fortifying breath before he followed inside.

Beneath the deck, the air was a poisonous fume. Ellengaest advanced, guided by half a dozen flickering candles lining the corridor, ignoring the gleaming eyes that followed his progress from behind iron bars. The passage rocked and swayed, and there was a soft clink from either side as the prisoners stirred.

By the time he reached Galti and Unndor, the cell before them stood open. He stepped inside, taking a candle from Galti, which illuminated two wooden bunks. The top one was empty. The bottom supported a shackled prisoner, who sat up stiffly to face the newcomers, squinting in the candlelight.

“Leave us,” said Ellengaest. Galti retreated, his footsteps fading down the passage, and Ellengaest, Unndor and the prisoner were left observing one another.

Urthr Uvorenson had been put in this fetid belly by Ellengaest himself, though he probably did not know that. He had served three months of his sixty-year sentence and already looked a broken man. He was thin, his hair matted, his face watchful. Open sores covered his hands, and his nails were tattered from the endless work of grinding flour, unpicking tarred ropes and shattering metal ore. “Brother,” he said, eyeing Unndor. He turned his attention to the other visitor. “And I know you. You are Vigtyr the Quick—”

“Ellengaest,” he overrode. “My name is Ellengaest.”

Urthr stared at him, then he shrugged. “Why are you here?”

The visitor—the Ellengaest, Vigtyr the Quick—smiled at Urthr. “I’ve come to see if you would like to walk free.”

Urthr gave a brief, flat laugh. He looked bitterly at his brother, sitting in the other corner, in rebuke at this cruelty.

“I do not make idle offers,” said Vigtyr.

Urthr shrugged. “And how could you arrange that?”

“I could take you with me tonight,” said Vigtyr. “Your brother and I arrived by boat, tethered outside. It is as simple as you agreeing to help me, and then the three of us will take that boat back to shore.”

Urthr examined him. “They would stop us.”

“The captain,” said Vigtyr, leaning forward to watch Urthr’s reaction, “is quite considerably in my debt. We have a good arrangement. I maintain silence about what I have done for him, and in return I have access to the prisoners I need.”

There was a look of incredulity on Urthr’s face. “What have you done for him?”

“If I told you, it would erase the debt.”

Urthr held up his hands, showing his manacles. “I am tempted by any agreement that gets me out of these. So what do you want from me?”

“It is not what I want from you. It is what I want for you. For both of you,” he added, indicating Unndor. “Revenge. On the man who killed your father and put you in here to rot for crimes you did not commit. We are going to tear down the Black Lord.”

There was a slight movement as Urthr examined his brother’s face, then turned back to Vigtyr. “And why do you want this?” he breathed.

“Your freedom is in your hands,” said Vigtyr, “but you may startle it away if you’re too rough.”

Unndor spoke then, leaning forward from his corner. “But you cannot simply expect us to trust you. There are rumours about you. How can you bring down Roper? How could you do it, when our father could not?”

“There is a man below the Abus,” replied Vigtyr. “A Sutherner of unusual cunning, who has let it be known that he needs spies.”

“Bellamus,” said Urthr, unimpressed. “Perhaps the Black Kingdom’s greatest enemy. You want to use him?”

“I will use him. And I will use the Kryptea. And you will help me, or you’ll rot here. Those are your choices.”

The darkness thumped as someone walked the deck overhead, and the three could almost sense the straining ears tracking their every word. “I know you,” said Urthr at last. “I know your reputation. You come here offering a great deal, but there is no payment I can imagine that would satisfy you. What would it cost me to be in your debt?”

Vigtyr shrugged. “Nothing you treasure. Nothing you haven’t already lost. I need messengers. I can’t regularly head south of the Abus to contact the spymaster, it would be obvious, and I’d be missed. That is where you two come in. No one will miss you. You will have your freedom, and you will have revenge on the man who killed your father. Will you take it?”

There came a pause. Then Urthr began to laugh. It was a noise so uncontrolled that even Vigtyr leaned back a little, eyeing the prisoner. The laugh rattled beneath the deck like a die in a wooden cup. Urthr fell silent, his wrists tugging at the shackles that linked them. “Yes,” he said. “Get me off this hulk and I’ll do anything you want, but especially kill Roper Kynortasson.”

“And you?” said Vigtyr, looking at Unndor.

“Of course,” he said. “Of course. Though I doubt you will find the madmen of the Kryptea easily controlled.”

“The Kryptea are the smallest part of this,” said Vigtyr dismissively. “In the war that is coming, every soul will be involved. Suthdal is weak. We will need to uncover every enemy that Roper has and rally them against him. And not only him. Those close to him will die too.”

Urthr was smiling still. “Who?”

“His brothers are first,” said Vigtyr. “If they are not dead already, they will be within days. The man I have set on them does not fail.”

The pair eyed Vigtyr for a time, the only sound the creak of the boat’s timbers. “When do we begin?”

Vigtyr smiled. “We have begun already.”

The Black Lord was a tall man, though not as tall as often supposed. He held his back very straight; his hair was dark, his face robust and stern at rest. But that was an illusion, and his attention, if you gained it, was consistent, personable and intelligent. He was a man of sharp edges, concealed by a practised and deprecating manner. It was only the very few close to him who saw the ticking heart like a clockwork spring that drove him on, on, on. And at this moment, his face had assumed the distant mask he often wore in times of turmoil.

Because his brother was dead.

He stood, wrapped in a dark cloak, on a white sand beach at the head of a long lake. The only person within ten feet was a tall woman with black hair and poisonous green eyes, she too enfolded in a dark cloak. Her name was Keturah, and the pair of them stood slightly apart from a score of mourners, buffeted by the wind rushing the length of the water.

Along the lake’s edge, some fifty yards away, a procession was approaching. A dozen boys, no older than twelve, walking together in two parallel lines.

They were carrying a child’s body.

A grey, limp presence held awkwardly between the lines. The mouth was a dark ellipse. The arms, like slim boards of willow, bounced with each step. The flesh was naked but for a layer of charcoal, and a chain of raptor feathers clutched at its neck, and behind the procession a vast stretch of a drum thumped with each step they took.

Dow. Dow. Dow.

Roper did not notice the drum. He did not see the mountains enclosing them on three sides in a sheer verdant wall, or the grey waves swept up by the wind. He was lost in the memories that swarmed this place.

He remembered a still day on this very beach, when he and the dead boy had been engulfed in a cloud of midges. He remembered how they had run up and down the beach to try and lose them, but wherever they went, still more waited for them. How they had plunged into the waters of the lake to wait for the return of the wind, and found it too cold. They had finally taken refuge in the smoke of their fire, which though he had to breathe hot fumes, Roper found preferable to the swarm beyond. He had said he was going to make a dash for their cloaks, and his brother had declared that the midges would have reduced him to a skeleton by the time Roper returned. They had joked that together, they would spend the rest of their days attempting to find the Queen Midge, should such a tyrant exist, and destroy her as a favour to all humanity. Surely they could do no greater good.

He remembered the moon-blasted night they had fished together on a promontory at the far end. How he had been surly because his brother had caught two fine trout, and he had managed nothing. He remembered the last time he had seen Numa, standing on this beach with the iron clouds stretching behind him. Roper had turned in his saddle as he rode south with two unfamiliar Pendeen legionaries. He remembered how Numa and his twin had looked back at him and had not waved: merely shared one last look before Roper turned away. He remembered the steady metallic hiss of the rain stinging the flat lake. He remembered the cold of it running down his cheeks and over his lips. He remembered it all, but could feel no grief. All he had was the restless ticking in his chest, seeking revenge.

The procession was drawing near the grave at Roper’s side, its earthen walls impressed with interlinking handprints, like a canopy of leaves. As it came close, the mourners began to sing: a gentle lament that quivered and shook, swelling with the body’s approach, and presently becoming a funereal howl that almost drowned the reverberations of the drum. One of the singers standing by the grave was the double of the corpse, his face a tear-stained mirror to the scene before him. Gray was next to him, singing with the others, and placed a hand on the boy’s heaving shoulder, eyes not leaving the swaying body.

It was manoeuvred into place above the grave, head facing east, and close enough that Roper could see the lacerations in the skin, cut to ribbons to hasten the moment his brother’s bones rotted into the earth. The dark limbs were folded to the body’s side. For an instant it floated above the grave.

The reverberations of the drum faded and the singing fell away. Even the wind fell still.

Then the body dropped.

It plunged into the earth, a filthy embrace whooshing up in reaction. There was a distant thump as the corpse hit its resting place. Then Numa’s peers and his stricken twin began pressing the piled earth forward with their bare hands, filling in the grave. Roper turned away then, receiving a momentary assessment from the green eyes at his side.

“Now we find out who killed him.”

“Master.” Roper caught the eye of a stooped, ancient man robed in black, and hailed him, remembering too late to lift the thunderous frown from his brow. The Master of the haskoli and Roper met amid the embracing mourners and shook hands. The Master’s was a swollen talon, cold and lumpen, and the face above it so lined it resembled a piece of parchment stored at the bottom of a travel-sack. Keturah and another woman in dark robes joined the pair of them, and the Master offered Roper a gentle smile.

“A sad day, lord.”

“Yes, a sad day,” Roper agreed. “But my priority here is discovering why this day has come at all.”

The Master’s smile did not relent. This was the man who had overseen Roper’s own time in the haskoli, whom Roper had feared and admired without limit as a student. The Master had been a Sacred Guardsman once, but injury had forced him into the mountains. He still possessed an unmistakable aura though: that of a man who has had the threshold at which he becomes agitated breached and reset so many times that it was now near unreachable. “I’m so sorry, my lord. Events such as this are not unheard of.”

Roper narrowed his eyes. “I’m not sure I understand.”

The Master interlinked his fingers over his chest. “These boys are pushed very hard, my lord, as you will remember from your own time here. We initiate them into the sacred art of war. They learn not to back down under any circumstances, and there is a fierce rivalry between their groups. Sometimes, that gets out of hand. I have seen it several times now. It is usually a fight that has gone too far. No malice, nothing out of the ordinary—just an accident, from boys who are testing their limits.”

“You think one of Numa’s peers did this?”

The Master nodded. “That is the most likely explanation, lord.”

Keturah, who had been listening closely, made a brief impatient noise. “Hm, do you really think so?” she said, tucking her hair behind one ear. “Perhaps that would be true if this were a normal student, but Numa is the brother of a Black Lord who has just defeated a very powerful enemy. This is surely the remnants of Uvoren’s power-block at work. I’m sure the Inquisitor will support me,” she added, gesturing to the woman by her side, who gave an approving smile. Her name was Inger and she was a little over a hundred years, with greying hair and a round, pale face. She wore black robes with a dog-headed angel inscribed on her chest in silver thread, and white eagle feathers rippling through her hair. Inger usually seasoned these marks of office with a vague smile, giving the impression that she was unaware of even her immediate environment. She had spent most of the journey here making their party laugh with awkward and singular observations, but Roper knew that she could not possibly be as hazy as she appeared. It took a mind of unusual insight and dedication to reach the rank of Maven Inquisitor.

“Not impossible,” the Master replied to Keturah. “I can only tell you what seems most likely to me, as someone who has overseen this school for two dozen years. If this had been Uvoren’s men, they would surely have wanted to make it clear this was not a random act and chosen a more overtly violent method. Unfortunately, Numa seems to have been killed by hand.”

“The timing is more significant than the means,” opined Keturah.

“I agree,” said the Inquisitor, distractedly.

“We will discover the truth, one way or another,” said Roper abruptly. Not for one moment did he believe this had been an accident. “I am leaving two guardsmen here: Leon and Salbjorn, to aid the Inquisitor.” Roper indicated two armoured men who stood nearby, observing the conversation silently. Leon was massive and dark, with a crudely carved rock of a face. Salbjorn, standing next to him, was his protégé: small, wiry and blond, with a pointed chin and angular cheekbones. “Salbjorn will help with the investigation. Leon will protect Ormur.” Roper named Numa’s surviving twin.

The Master inclined his head. “As you wish, lord. They can have quarters up at the school.”

“I thank you for your help, Master,” said Roper. “Time is against me. I will speak with my brother, then I must go.”

The Master bowed and Roper tried to slip into the crowd of chattering mourners. But they shied away from him, every one of them aware of his person and backing away swiftly. Roper ignored this, casting around for his younger brother. He saw him almost at once: a solitary figure standing at the water’s edge, the lake lapping at his bare feet. Roper went to join him, the two of them staring out over the water together.

Ormur was small for his age, as Roper had once been. His features were still expressive and endearing, yet to develop into the strong mask of a mature Anakim, and reminiscent to Roper now of the Sutherners. He tried to think what to say to the boy, who did not seem to have noticed Roper’s approach. “Are you all right?”

“Yes, lord,” said the boy.

“What happened?” asked Roper, unable to think of anything more helpful to say, so succumbing to the question he most wanted to ask. “I heard you found his body.”

“I found him, lord.”

“Don’t call me lord, Ormur.”

“I found him. We were fishing off Cut Edge,” said the boy, giving a listless wave up the lake to a steep drop, overhung with branches and beneath which the trout liked to linger for the insects that fell into the water. It had been a favourite fishing spot in Roper’s own time here. “We’d had no luck, and he wanted to go and set some baited lines by the shore. I kept fishing.” Ormur’s face began to warp and Roper placed a hand on the boy’s arm, turning him away from the water.

“Look at me, brother.” He stared into Ormur’s grey eyes. This was not the roguish, impish character that he remembered. “Take a deep breath.”

Ormur seemed steadied by Roper’s touch. He closed his eyes for a long moment, drawing in the mountain air.

“Are you ready?”

Ormur nodded. “He didn’t come back. I stayed fishing until late. We had a moon, I was waiting for him. It was dark before I packed up and went to find him.”

Ormur’s grief began to resurface, and Roper intervened quickly. “Did you get any fish?”

“I got a char,” said the boy. “Not a big one.”

“I miss char,” said Roper, watching his brother carefully. “That is the smell everyone says they associate with the haskoli, when they have moved on. Char, roasting over the fire.” The break in the conversation had given Ormur a little time to gather his energy, and Roper waited now for him to go on.

“I found him down on the shore of the lake,” said Ormur, his voice grotesquely suppressed. “He was so pale, under the moon. One of his arms was underneath him, and one of them trailing in the waters of the lake. I didn’t realise he was dead. I thought maybe he’d slipped and hurt himself. And then I turned him over—” Ormur coughed, his eyes dropped, his chin followed, his chest heaved, hiccoughed, and then he broke over Roper. His head leaned into Roper’s chest and he sobbed wretchedly, a keening so animal that Roper could feel it plucking at his flesh. He raised his hands to the boy’s shoulders and held him there, leaning his head into his brother. Ormur was trying to go on, and Roper shushed him, but the boy would not be stopped. Between each heaving breath, each gasping sob, he forced the words free. “He… was… strangled!” He hauled in three rapid breaths. “His eyes!”

“Stop,” said Roper, firmly.

They waited there, the two of them. “I’m sorry, brother,” he murmured into Ormur’s head. “I’m so sorry. We will find them, you know. Whoever killed Numa. We will find them and make them pay.”

Ormur’s shoulders were no longer heaving, his sobs replaced by deep, slow breaths.

“I am leaving an Inquisitor here with two guardsmen. The Inquisitor and Salbjorn will find Numa’s killer. Leon will protect you.” The boy made no reply. Roper released him, and he straightened up. “Do you think it was one of the boys here who killed Numa?”

Ormur shook his head at once, his grief-stained face resolving into certainty. “No. No.”

“Neither do I,” said Roper. He gestured back at the crowd of mourners, most of whom had begun to drift away from the lake and up towards the school. The two of them followed, walking in silence for a time. “You know what week it is?”

“Hookho,” said Ormur. The week the cuckoo begins to call.

“Good,” said Roper. “And next week?”

“Gurstala?” hazarded Ormur, naming the week the bluebells flower.

“You’ve skipped two of them.” It seemed odd to Roper now, but he remembered being as ignorant as Ormur during his own time in the haskoli. Each Anakim week was named to reflect some seasonal event, but the mountains of the school had their own climate and their own pace, and the weeks had seemed as arbitrary to Roper at the time as they were evocative now. “Next week is Pipalaw: the week rainbows bloom.”

They drew level with the score heading back up to the school. “Take care of yourself, brother. Work hard. And stay safe. It will get better.”

Ormur looked glassily up at Roper, managed a brief nod, and turned away, following the group around the lake and towards the haskoli. Roper spotted three figures standing and waiting for him: the two Sacred Guardsmen and the Inquisitor. He went to join them and took each of their hands in turn, before staring at them in silence.

“I will find whoever did this, lord,” said Inger, smiling back at his poisonous expression. “I always do.”

“Leave no stone unturned,” said Roper, in a low voice. “Give him not one moment’s rest. Follow him as a pack of murderous dogs and make him know ravenous fear. Pursue him onto the Winter Road and beyond if you must, and when you have him, bring me his head with two empty eye sockets.”

“It shall be as you wish, lord,” said Inger.

Roper observed them all for a moment longer. “Good luck.”

The Anakim and the Sutherner, two of the races that inhabited Albion, did not share much. To the Sutherners, the world was filled with colour: to the Anakim, memory. The Sutherners loved to travel where the Anakim hated it, delighted in personal adornment where their neighbours scorned it, and subjected their lands to the yoke of agriculture, where the Anakim adored wilderness. Their laws were different, their customs deliberately diverse, and two fiercer enemies never existed. But revenge, at least, bound them. With either race, if you take a mother, father, sister or brother from them, no matter how complex their relationship was, you have violated family. Expect neither rest nor mercy until you have been violated in turn.

Though the air at Lake Avon carried the immaculate signature of altitude, the haskoli—the harsh school where boys were sent at the age of six to become legionaries—was set even higher, behind one of the mountains that bordered the lake. The climb to reach it took some two hours, and by the time Inger and her sacred escort had arrived, dusk was falling. The trees had shrunk and fallen away, and thick drifts of snow shone like burnished silver beneath a crescent moon.

The school was cut into the mountainside, sheer cliffs on three sides providing small protection from the elements. The buildings were completely uniform: a dozen longhouses, with timbers of straight red pine and thatch of heather, lining a central courtyard of sand, rock and drifted snow. Another, smaller lake spread before it, its icy surface rough from repeated shattering and freezing. Behind the school reared the shadow of an ancient tree which had somehow weathered the mountain winds: a single towering pine with only a dusting of needles remaining at its top. The rest of the branches were draped with hundreds of ragged raptor wings that fluttered darkly in place of leaves.

“Home, for the next while,” said Inger lightly. “As it’s dark already, I say we settle in tonight and begin our investigations first thing tomorrow.”

The guardsmen murmured their agreement, and they were led by a black-cloaked tutor into the nearest longhouse. The interior was very dark and suffused with the resinous scent of pine. They climbed a creaking flight of stairs, laid down their packs on the goatskins that bristled the floor, and emptied them in silence. Before long, Leon snatched up his sword and stalked out, saying he would sleep outside Ormur’s quarters.

“Like a dog,” muttered Salbjorn, laying out his own equipment for tending, and lighting four smoky candles to guide his work. “Do you really think the assassin is still here?” he asked, settling heavily on the floor and pulling a pot of fatty grease towards him. He began to work it bare-handed into his boots.

Inger watched him vacantly. “What do you think?”

The guardsman’s shadowed face turned towards her briefly, then back to his boots. “He’s gone. You don’t kill the brother of the Black Lord and then linger at the scene of the crime.” When Inger made no reply, Salbjorn glanced at her once more. “Do you?”

“It depends why you’ve killed him,” said Inger mildly.

Rain began to tap on the thatched roof and pour past the window in a fragmentary curtain. “Do you have any suspects?”

“Many,” said Inger. “The Black Lord has a lot of enemies, and it could be any one of them. Uvoren’s two sons, Unndor and Urthr, live in disgrace or in gaol, thanks to Roper. Perhaps it is a friend of theirs. Tore, Legate of the Greyhazel, was a friend of Uvoren’s from their days together at this haskoli. He commands a lot of men: maybe it was one of those, acting on his orders. The same goes for Randolph, Legate of the Blackstone. Or this might not be related to Uvoren’s death at all. Never underestimate how mad the Kryptea can be, and what strange motive they can find for almost any death. Or maybe this was Suthern work. Assassins from Suthdal, in repayment for the massacre atop Harstathur. Perhaps the Sutherners decided Roper’s brothers would be more easily targeted than the man himself.” Inger fell silent, staring at a sputtering candle. “That’s just a start. There are dark forces at work in our kingdom, doing things that we do not yet understand.”

True darkness had fallen outside, and the rain drummed through the room. Salbjorn finished his boots and moved on to the rest of his equipment, adding each piece to a neat pile as he finished tending it. His cuirass bore gouges, dents and pocks, but not a speck of rust, dirt or blood. The chain mail beneath it was speckled with distorted links, but gleamed like water pouring through sunbeams. And the long sword, propped against the wall and unsheathed to allow its fresh oil coat to dry, had small chips and dinks all along its length, which was nevertheless sharpened to a pitiless edge.

“Can you smell smoke?” asked Inger suddenly, stirring from her dreamy reverie.

Salbjorn gestured towards the pot of grease. “It’s this.”

“No, I smelt that before,” said Inger, getting to her feet. She turned to the window, staring out into the school’s rain-spattered courtyard. She could see nothing for a few seconds. Then her eyes accustomed to the dark outside, and she perceived the crimson glow flickering the ground in front of their longhouse. She could see no flame, but that was because it was out of sight bene

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...