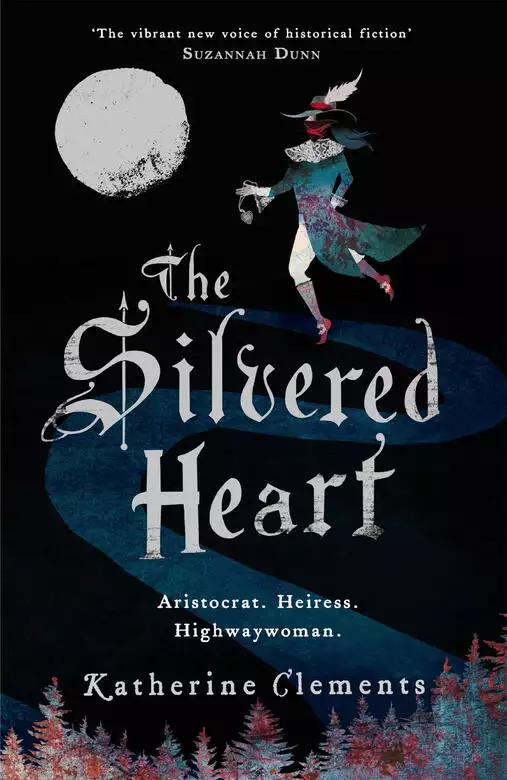

The Silvered Heart

- eBook

- Paperback

- Audiobook

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

1648: Civil war is devastating England. The privileged world of Katherine Ferrers is crumbling under Cromwell's army and, as an orphaned heiress, she has no choice but to marry for the sake of family.

But as her marriage turns into a prison and her fortune is forfeit, Katherine becomes increasingly desperate. So when she meets a man who shows her a way out, she seizes the chance. It is dangerous and brutal, and she knows if they're caught, there's only one way it can end...

The mystery of Lady Katherine Ferrers, legendary highwaywoman, has captured the collective imagination of generations. Now, based on the real woman, the original 'Wicked Lady' is brought gloriously to life in this tale of infatuation, betrayal and survival.

(P)2019 Headline Publishing Group Ltd

Release date: May 7, 2015

Publisher: Headline

Print pages: 448

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Silvered Heart

Katherine Clements

The distant drum of galloping hoofs conjures nothing but doubt and fear, these days. I am the first to hear it – a far-off rumble, creeping to the fore, pushing other thoughts aside.

My maidservant, Rachel, nods on the bench opposite, head bobbing and swaying with the motion of the carriage. I don’t know how she can sleep. My own mind is so busy I’ve barely rested in the two days since we left Markyate Cell.

Our journey has become a slow crawl across England’s lead-pocked, battle-churned land. In my stepfather’s coach the seats are hard, the hangings plain, and the cushions have long since shed their down. My bones ache, bump and bruise with every jolt of the wheels.

We cannot travel in comfort, for that would attract the attention of thieves and brigands, but Sir Simon insists that his stepdaughter must arrive in the manner most fitting, despite the danger on the roads; the cramped, heavily armed and escorted carrier might be safer, but it’s no transport for a Fanshawe. Nor can they spare arms to protect us, for any honourable man is gathering his strength and his guns and preparing to fight the Roundheads once again. With the King imprisoned at Carisbrooke, and his men turning traitor every day, not a single steadfast soul can be spared, and certainly not for me. We must all take risks for the sake of King Charles.

I hear the sharp swipe of the whip as Master Coleman, our driver, spurs the horses on. The pair of greys we switched to at Bedford do not have the strength of Sir Simon’s own, but the coach bounces in the ruts as we gain a little speed.

Rachel wakes, rubs her eyes and wipes the corner of her mouth where drool has crusted. ‘Is it evening so soon?’

I pull back the leather flap at the window to show her dusk creeping through the trees. The sun is low and fiery orange, dazzling through the branches to play tricks on my eyes. The sky is turning red. The thrum of horses’ hoofs draws closer.

‘They said we’d reach Hamerton before dark,’ she says, frowning. ‘Lady Alice will fret if we don’t arrive by nightfall.’

The riders are clearly ahead of us, the rolling thunder suggesting a number of men on the road. Rachel registers the noise, forehead creasing. ‘Who could that be?’

I say nothing, but she must read the fear in my eyes, because she reaches across and circles my fingers with hers. ‘I’m sure they’ll pass us by.’

There is movement above – George, the coachman’s boy, turning back along the roof to fasten the straps on my trunks. Master Coleman cracks the whip and the horses break into a reluctant canter. Rachel is thrust forward into my lap.

Both of us let out a cry of surprise, but before I can call out to Coleman, there is a sudden blast and a whump as something hits the rear of the carriage. A small round hole appears in the back panel, just to the right of my head, sending a shaft of golden sunset streaking across the gloom.

Rachel clutches my arm, panic-eyed. ‘What, in God’s name—’

There are voices up ahead, the echo of men’s shouts amid the trees. Then, one voice raised above the others: ‘Hold your horses or pay with your lives!’

My heart climbs into my throat.

We judder to a stop, the horses whinnying their protest, harnesses jangling, like discordant bells.

Coleman’s voice calls urgently from above. ‘Keep inside, Lady Katherine . . . and stay silent.’

I can guess what is coming. It is the thing that all travellers must risk in these days of misrule, when men make opportunity from misfortune. The lucky charm that Lady Anne pressed upon me will do nothing to protect us from bandits and outlaws. A swarm of them infects the roads like a plague, plundering at will, with no one able to prevent it. We have a musket, tied between the chests on the roof of the carriage – a better hope than any trinket, but poor protection against the ruthless demands of the lawless, and at this moment, out of reach.

I see the barrel of a pistol before I see the man, its round, black mouth no bigger than a penny. Then the leather flap at the window is torn aside and a face appears in its place. A filthy brown kerchief covers the man’s nose, mouth and chin. His hat is pulled low, leaving only squinting dark eyes and heavy brows in view. He stares at me. Rachel pulls herself onto the seat, positioned between us. Her expression is defiant but her hand, settled protectively on my knee, trembles.

The man tugs the door open.

The pistol twitches. Once. Twice. ‘Get out.’

My legs are weak and my heartbeat rapid as I step down from the carriage. I stumble, clumsy and tripping in the mud. Rachel follows and puts her arm around me.

‘Be strong, Kate,’ she whispers, close in my ear. ‘Don’t show your fear.’ But there are no tears in my eyes: terror is trapped in my chest, squeezing my lungs, binding my breath. She grips my hand tight.

I can smell them: three men stinking of rot, liquor and the latrine – the stench of scum. One, still mounted and holding the reins of two other scrawny nags, nervously watches the road. A second stands by our coach horses, pistol trained on Master Coleman, who sits on the driver’s seat with George, hands surrendered to the sky. His face quivers, the spark of fury in his eyes. For an older man, I know he still has some fight in him – among Sir Simon’s stable lads, he is known for boxing ears.

The man who turned us out of the carriage lowers the pistol. ‘Do not think to tarry with me,’ he says. ‘I’ve no patience for weeping women.’ His voice is gruff, as though he has swallowed flint.

He searches inside the coach and pulls out my travelling pack. He upturns it, emptying it into the mud. My discarded needlework, a book and the doll, Henrietta, which I could not leave behind, tumble out. Henrietta’s dark curls splay on the ground, yellow-white painted pearls matching her teeth, her smile serene as always. Lady Anne was wise when she bade me leave behind my mother’s jewels.

The man is not satisfied with this girlish plunder and steps back to scan the coach, his eyes narrow and searching, like those of a rat seeking scraps.

‘The trunks . . .’ he says, indicating the luggage tied atop the carriage. ‘You, boy, throw them down.’

George looks to Master Coleman, who gives a grim nod. He stands, swaying slightly, giving away an uncharacteristic lack of deftness, and starts to untie the straps.

The man turns his attention to me. He levels the pistol at my chest.

‘Take off your cloak.’

I lower my hood and unfasten the cord at my neck with fat-witted fingers. The heavy grey wool drops to the floor.

‘I knew it,’ he says. ‘Ripe for the taking.’

Although I cannot see his leer, I sense the stirring in him. I have heard that cracking thickness in a man’s voice before.

‘Come closer,’ he says.

I back away, still clinging to Rachel’s hand. She stands before me. ‘Leave her be.’

‘Move aside, girl. Unless you want the same.’

‘If you touch them, you’ll regret it,’ Master Coleman says, voice full of threat, but one of the others raises a pistol and demands silence.

The man grips my arm and drags me away from the roadside, taking me down a steep bank, through bracken and brambles, thorns tearing at my skirts, the pistol dug hard against my ribs.

Rachel cries out, ‘Please, no! She’s barely more than a child . . .’

I twist to look back over my shoulder just in time to see the second man go towards her, while the third trains his gun on George, now lowering the luggage from the roof.

My captor’s fingertips dig into my flesh, even through the thick layers of my winter travelling gown. My arm feels as though it might snap like a twig. My heart patters, a bitter tang rising on my tongue. I cannot tell whether the sound in my ears is the rushing of blood or the wind in the trees.

I can no longer see the road or the carriage, though the echo of Rachel’s pleading winds eerily through the canopy like birdcall. The man pushes me up against the wide trunk of an old, dead sycamore and brings the barrel of the pistol level with my chest.

‘Your jewels. Where are they?’ His fingernails scratch my neck. He finds the thin chain of silver that is always fastened there and slowly draws the pendant up and out from beneath my bodice. ‘Here’s a fine treasure.’ With a swift, hard tug he breaks the chain and dangles it to take a better look. The polished silver heart gleams in the fading light, brilliant as the rising moon. ‘A pretty trinket. Where’s the rest?’

‘I have no other.’

‘Don’t lie to me, girl.’ He slides the barrel of the gun up my neck to rest against my cheek. I try to turn my face away but he catches hold of my chin, digs his nails into my jaw and forces the maw of the pistol between my lips. It clashes against my clenched teeth. I taste smoke and iron. His eyes follow the path of the gun and I see their dark points widen. He holds me there for a few seconds. I dare not move, nor even breathe. I close my eyes, too afraid even to pray.

‘Money, then.’ He releases me slightly, slides the barrel from my mouth so I can reply.

‘In the trunks, what little I have.’

His free hand moves over my waist, my bodice.

‘Your pocket?’

I fumble for the small pouch, hidden always in my petticoats. My fingers are clumsy as I untie the knot and offer it to him. He snatches it away, the paltry contents spilling into his palm. He snorts. ‘There must be something else worth having in those skirts.’

‘I swear, I have nothing of value.’

He bends and places the pistol on the forest floor, never taking his eyes from mine, and then, before I have the wit to run, his hands are on me, tearing at my lacings.

‘Please, no . . .’

He bats my hands away and lands a stinging slap across my cheek. Sharp, bright pain explodes across my jaw, making stars before my eyes. He tugs at my stays until he can slide his fingers beneath. He makes a low growl, like a hound, as he finds flesh. He squeezes my breast hard.

I try to fight, finding strength in my panic, but he pushes up against me with such force that the air is squeezed from my lungs, and I am crushed against the bark. The stink of him, like a long-dead carcass, makes me retch. As his face comes close to mine I catch the stench of rotting teeth beneath the kerchief, and rank traces of sulphur. In the struggle I knock his hat to the ground. Rat-brown hair is shorn close to his scalp, a few longer strands plastered against his neck, but there is a patch where there is no hair at all and the skin is red and scabbed: a wound of some sort that oozes, slick and yellow. His eyes are dark, flat, without depth, without even a haze of lust. They are the eyes of a dead man, the eyes of a ghost.

His hand searches beneath my petticoats until he finds skin.

No man has ever touched me there. I begin to sob and plead. Strength deserts me as my body begins to quake. He is forceful, moving towards my centre. I shut my eyes and beg: Please, God, do not let this happen. Not here. Not now. Not this man.

From the road comes the sharp retort of gunshot. Once. Twice. Rachel’s scream echoes through the trees, like a fox’s cry. My heart plunges and tilts. The man hesitates for the briefest moment. I think that he means to rip off the kerchief and kiss me with that foul mouth, but instead he finds the place between my legs.

Fear gets the better of me then. My body rebels. A stream of hot wetness gushes over his hand. It does not stop him. He seems to like it. He enjoys my terror.

‘You dirty whore,’ he says, leaning up against me. I feel him harden against my thigh as his fingers stab inside. I sense it then – a breaking apart deep in my chest, as something shatters like a dropped looking glass. The silvered shards protecting my soul crack and cloud with black, broiling smoke. The choking stink of charcoal and scorched bone fills my nostrils. I cry out; part pain, part despair. Above me, the ancient, twisted boughs of the sycamore tree stretch away like the Devil’s claws. Amid the flaming red sunset, a single star blinks bright.

The air cracks and there is a rushing, whooshing sound. I feel the sudden impact as something hits the man, forcing the weight of him further against me. Then he arches backwards, making a strangled cry. He twists away, hands leaving my body, clutching at air instead. My gaze finds George standing atop the ridge at the roadside, smoking musket at his shoulder, face curd-white against orange hair, the gun heavy in his hands.

My captor slumps to his knees, face twisted in a grimace of angry shock. I slide away from the trunk as he falls at my feet with a strange burbling moan. There is a small red hole in the leather of his coat where the bullet pierced him.

There is another shot and George is tossed backwards with a yell. I see the man on horseback, struggling to reload his pistol, as his mount bucks and dances.

I grab the flintlock from the leaf-strewn floor. It’s loaded and cocked. All I need do is pull the trigger. Suddenly I’m five years old, back in the parklands at Markyate Cell, watching my brothers at their marksman practice. My father’s voice comes to me: ‘Use both hands, and steady yourself before the shot.’

I take aim. I pull the trigger. My hands are shaking and the bullet goes wide, but it’s enough to cause the horse to fright, almost dumping the man on the road. He struggles to keep his seat, then holsters his pistol, wheels about, dragging on the reins, and takes flight away to the south.

I drop the gun. It lies smoking at my feet. My chest heaves. The man is still and silent, no breath left for him. Quickly, I reach into the pocket of his coat and take back my necklace, then push my way through the bracken to George.

He is awake, eyes rolling like those of a wounded deer. The shot has grazed his arm, taking the flesh with it. I see pale bone amid the mess of gore. His face is grey, sheened with sweat, and his teeth are chattering.

I shout for Rachel. Searching for her in the gathering dusk, I find her standing by the carriage, staring at something on the ground, perfectly still, fixed by what she sees.

George is bleeding fast. I recall something I once saw done by my father’s groom, who nursed a dog hit by shot, mistaken for a hare. I tear at my petticoats, now damp with my own waters, ripping away a strip of fabric and knotting it tight around George’s arm, above the wound. He cries out and tries to push me away.

‘You must stand it, George,’ I say. ‘It’ll slow the bleeding. You must stand the pain.’

He grits his teeth, fixing me with a determined stare. Although he is taller than I, I manage to help him to his feet. He loops his good arm around my shoulders and we struggle towards the carriage. Thank God, the horses have not bolted, but they are twitching and stamping, ears flattened and eyes showing white.

As we reach Rachel, she turns her face to us, eyes dark with horror. There are two bodies on the road. One of the robbers, the man who held our horses, lies in a puddle of blood. His throat is slit. His mouth gapes, tongue lolling, fat and dripping red. The second is Master Coleman’s, but I know so only by the little Fanshawe crest sewn upon his coat. His face is a ruin, a mess of flesh and bone, one eyeball dangling above the crescent moon of his teeth. There is a bloodied dagger, still clutched in his hand. George emits a low whimper. My stomach heaves. I swallow down the rising sickness.

There is no time for grieving. The light is fading fast and we must be away from here before it is dark. I dare not guess what fate awaits us in the woods after nightfall. The sound of shots will surely draw ruffians from miles around. The sense of urgent danger seems to clear my mind rather than cloud it. I’m determined to reach Hamerton before it is too late.

‘Rachel, take George inside the coach,’ I say. She pulls her eyes from the grisly scene to find mine. ‘Do as I say.’

She falters as she sees George’s injury, but she takes my place at his side and helps him into the carriage.

I cannot rescue the trunks, or save my belongings that lie strewn about the place, but I snatch up my woollen cloak, and the doll, Henrietta, now lying face down in the dirt, and toss them both inside the carriage.

Climbing up to the driver’s seat, I gather the reins. I’m not sure the horses will answer to my voice but I urge them on, as I have seen others do so many times. They prick their ears and start to move. The coach lilts, like a boat at sea, and it takes a few faltering attempts but finally the suck of mud releases the wheels and the coach moves ahead.

I twist in my seat to make sure we are not followed.

Then, I see it, glowing ghostly blue in the twilight – my wedding gown, lying in the dirt, torn and spattered with blood.

Chapter 2

I have not seen Thomas Fanshawe, the man who is to become my husband, in five years. Five years of war.

Our only meeting was at Oxford, the King’s court, in those days before the Roundheads stormed the field at Naseby, when we all believed our exile was temporary, our time in Oxford a happy inconvenience. The college cloisters were brilliant with silks and ribbons, the glitter of sapphires and emeralds, the heavenly chorus of lute and viola.

Thomas Fanshawe was a short, round boy, made up of coddled cream puddings and too many sweetmeats, not far beyond his tenth birthday. He was two years my elder, with a child’s preoccupations and a child’s temper. When I first saw him he was sprawled on his belly, next to a fountain in the gardens of Merton College, where the Queen had her rooms, and her women gathered to escape the fetid air of the city proper. The most fashionable ladies of the court were drawn there, to wander the gravel paths, smell the summer roses, or idle away time in gossip.

My mother had found a shady spot for us to sit, her hand, as usual, in mine. Thomas was floating a wooden ship on the circle of water – a finely carved thing, with silk sails and tiny flags, embroidered with the colours of the Fanshawe crest. His playmate, a scrap of a boy from the cellars, who should have known better, sent specks of gravel, like cannon fire, against the little boat. The boy, exuberant in his new-found freedom, unleashed one stone too hard. It caught a sail, tearing it, knocking the ship onto its side. The wreck bobbed sadly, waterlogged, adrift and out of reach.

Thomas attacked the boy before he had time to atone, barrelling into him, knocking him to the ground, fat fists pummelling. Their shouts echoed in the cloisters. A bevy of doves flapped skywards. Ladies looked up from their sewing, squinting against the sun to see what the fuss was about. But it was my mother who called Thomas to order. She clapped her hands for a page, and two appeared, wraithlike, from the shadows. They separated the scrapping boys, boxed the servant lad about the ears and dragged him off, protesting.

‘Bring Master Fanshawe to me,’ my mother said. Thomas, near to exploding with indignation, slumped towards us.

I studied this boy, my new-made cousin, from beneath lowered lashes, as my mother reprimanded him. His skin was pink, like fresh-carved ham, his full lips drawn into a sneer, his cheeks mottled. His eyes were brown and heavy-lidded. I noted the Fanshawe nose, the very likeness of Sir Simon – my mother’s new husband and my new father, who was not my father at all.

Thomas was still a boy then, on the brink of manhood, burdened with the awkwardness of not yet fitting into the body that God had given him. He did not seem to notice me, his small, young cousin by his new aunt’s side, except to glance at me, just the once, and I looked away quickly. When my mother had finished with him, he went, pouting and strutting, back across the garden to find some other scrape, the ship left bobbing, alone and forgotten on its small sea.

Five years have passed since that day. The court is no longer at Oxford because Oxford has fallen to Parliament’s army and there is no longer any court at all. Those rosy, glittering ladies, who circled the Queen, like bees to blossom, are scattered as petals in the breeze, husbands and lovers all dead, exiled or battle-broken. The sun-soaked idyll of Merton ended for me on the day my mother died, but it was not long before it ended for all the others too.

I know my betrothed has arrived because I hear the clatter of hoofs in the yard, the yelp of hounds, the echo of men calling for stable lads.

Rachel is at the casement, the torn petticoat she is mending cast aside. ‘They’re here,’ she says.

The chamber that George has been granted for the length of his recovery looks over the inner yard. Though my own room is much finer, with a view over the gardens to the orchards, it is from here that we can better see the comings and goings at Hamerton Manor.

In the three weeks since that awful night in the woods, we’ve spent almost every day in this room, keeping vigil over George. My aunt Alice, mistress of Hamerton, hears the story of George’s valour and names him the saviour of the Fanshawe family, as if all hope of that great dynasty lies with me. He is lavished with strong caudle, meat pies and good beer from the brewhouse. Rachel insists on dressing his wound herself, packing it with salve to stop the rot, making sure he gets good food from the kitchens, not the scraps usually kept by for servants. After a week of fevered sleep, he overcomes the sickness, his wound begins to heal and he is gaining strength.

But I have not had a moment alone with him to ask what I must. Only George knows the truth of what I suffered at the hands of the robber in the woods. Only he witnessed the devil’s touch upon my flesh, the fingers at work beneath my skirts. Only he knows that a musket shot saved me from worse. I’ve told no one, not even Rachel, swearing, when she asked, that the man did not dishonour me. I’ve swallowed the foul queasiness that rises when the memories come and I’ve kept my bruises well hidden as they yellow. They are almost healed now. When they are gone, that must be the end of it. George must keep my secret, because I fear Thomas Fanshawe would not take so tainted a wife.

I join Rachel at the window. There are six of them, young men, filling the yard with shouts and laughter, back-slapping, calling for ale, dogs yapping at their feet, stable boys scurrying around the horses, like vermin. They shed their travelling cloaks, revealing a rainbow of silk and velvet, the glint of gold buttons, the shine of silver swords, the lightning strike of white smiles. Capes whirl and hats are doffed as Aunt Alice bustles, hands clasped, thanking God for the safe arrival of her guests.

‘Which one is he?’ Rachel is impatient.

I cannot recognise the fat-faced boy with the sinking ship.

‘I don’t know,’ I say. But there is another I have noticed, who keeps himself apart from the others and is taller than the rest, older too – too old to be my husband. He has dark glossy curls and a serious, handsome face with a neat black beard.

‘They’re all sporting swords. Are they all soldiers? Have they all fought for the King?’ Rachel’s cheeks grow flushed. ‘Imagine . . . to be married to a hero.’

I shrug, but I know my future husband is considered too young, yet, for the King’s army, just as I am too young to take up the Ferrers’ estates. There has been no battlefield glory for him.

‘They’re all dressed very fine,’ Rachel goes on. ‘See the tall, dark one? Is that him?’

‘No, I think not.’ A glut has risen in my throat and my stomach feels alive with worms.

‘Ah, well, that’s good. You don’t want a husband so handsome that other ladies are always in love with him.’ She glances at me, waiting for a laugh that does not come. ‘What’s wrong?’

I have never been good at concealing my feelings – my mother used to say she could read the truth in my eyes as if she were reading scripture – but even so, Rachel has grown more attuned to my moods than most.

‘Don’t be afraid,’ she says, taking up my hands. ‘Thomas Fanshawe will not help but fall in love with you. You could have the pick of them, I’m sure.’

‘As could you,’ I say, in an echo of her faith in me.

She drops my hands and flaps her own in dismissal. ‘What would I want with a fine gentleman like that?’

She turns back to the scene in the yard, watching as the men follow Aunt Alice inside, taking the glamour and light with them, like a band of players. I notice that she bites her lower lip to bring up the colour, eyes sidling to the bed. She knows she has her fair share of charms.

Rachel is every bit my equal, in everything but breeding. Three years ago, when she first sought work at Markyate Cell, it was our mirrored looks first caught my attention. I do not need a glass to see how a bolt of cloth brings out the hue of my eyes, or how a new stomacher flatters my slim waist; I need only look to her. I soon realised that we are alike in other ways too. She is similar in nature, but with a steadier temper and a capacity for obedience I could never match. And we share a mirrored history, both understanding what it means to be orphaned too young and to find ourselves in circumstances we were not born to. I need no other companion to laugh at my follies, or cheer me when the grief returns. We are a matching pair, sisters, in everything but blood.

I look to George, laid back against the bolster. He is pale still, a rash of freckles across his cheek lending some colour. He looks like a child compared to the men in the yard, though he is certainly their equal in years. He has a peculiar, haunted look in his eye.

Rachel goes to him and rests her hand on his forehead. ‘Are you unwell, George?’

He pushes her wrist away and frowns.

She laughs nervously. ‘Pay us no heed. I’m sure none of them is as brave as you.’

But George fixes his eyes on mine and they are full of questions.

Chapter 3

I marry Thomas Fanshawe in a borrowed gown and worn travelling shoes.

Master Maybury, Aunt Alice’s steward, sent out a party to recover my things, but they tell me there was nothing to be found on the road, not even a bloodstain to mark poor Coleman’s passing. Whoever those men were, somebody made sure to cover their tracks.

The dress, belonging to Lady Anne – another Fanshawe aunt – is made of red damask so stiff it could stand alone to meet the priest. There are petticoats of fine cambric, intricately embroidered with a rainbow of flowers, vines and tiny insects. ‘Like the Garden of Eden,’ Anne says, stroking the shimmering threads as she hands them over. ‘Paradise beneath your skirts.’

Rachel gasps when she first sees it, whispering, ‘Red is bad luck for a bride . . .’ but she soon falls dumb under the weight of Anne’s glare.

As I am dressed and primped by a giggling flock of Fanshawe women, I feel like a doll, trussed up in someone else’s costume. Catching sight of myself in the glass, I barely recognise the girl looking back at me. I think of Henrietta, cleaned and mended now, face scrubbed of woodland mulch, sky blue silks puffed upon my pillow. If only I could scrub away my feelings so easily.

When I am ready, Anne shoos everyone but Rachel and me from the room. Anne’s own gown hangs loose and flowing over the mound of her belly, her stays barely laced. Her hair is sugared into tight little coils, glistening with the syrup that binds them. She hauls herself onto the bed, leans back against the bolster. ‘Ah, blessed relief. My feet are so sore.’ She pats the mattress. I cross the room and perch beside her.

‘Are you prepared, dear one?’ she says.

I need not answer for Anne reads the trepidation in my eyes. She takes up my hand. ‘I was a little older than you when I married my Richard, but I was a maid nonetheless and I know how you must feel. There’s no need to be afraid. We are all slaves to Nature and there’s nothing any of us can do about it.’ She cradles her belly. ‘This will be my fourth in as many years.’

I know that bedding is expected on a wedding night. I’ve watched enough newly-weds, drunken and laughing, borne away to their chambers. I’ve heard the bawdy comments of the groomsmen and watched the older women exchange know-it-all glances. But to imagine Thomas Fanshawe in my bed sends cold dread coursing through me.

I think of the man in the woods, the stab of his fingers, the stink of his breath, and the shame of the gushing wetness between my legs when I could not master my fear. Will my husband be able to tell that I have been touched in such a way?

‘Thomas will make a fine father, in time,’ Anne goes on. ‘And until then, Alice will look after you.’

‘What about the journey home? Will Thomas accompany me this time?’

‘My dear, given your youth, it’s wise to postpone your new life until you’re both ready.’ She twists towards me, hampered by her own weight. ‘You’ll stay here at Hamerton, out of harm’s way, until the time is right.’

‘But I thought to return to Markyate Cell . . .’

‘We cannot risk another misadventure on the roads. My Richard is sure there’ll be more fighting soon. You cannot go running about the country at whim. It’s far too dangerous.’

‘But Markyate Cell is the Ferrers’ house. It’s my home. It’s where I belong.’

‘I understand, Katherine, I do. As last of your bloodline the responsibility you carry is a great one, and it does you much credit that you wish to honour it. But by tonight you will be a Fanshawe. And Markyate Cell will be

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...