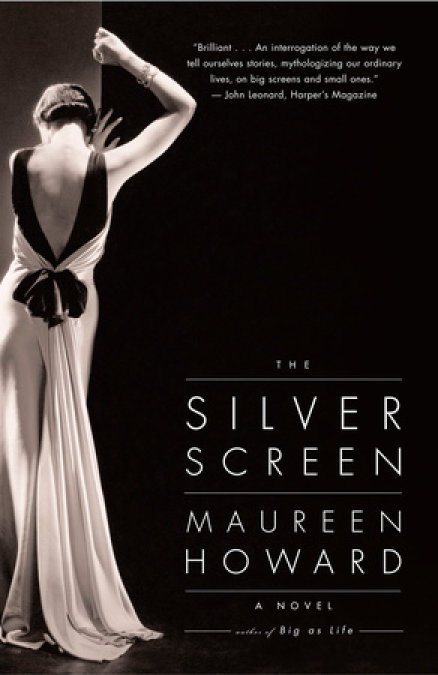

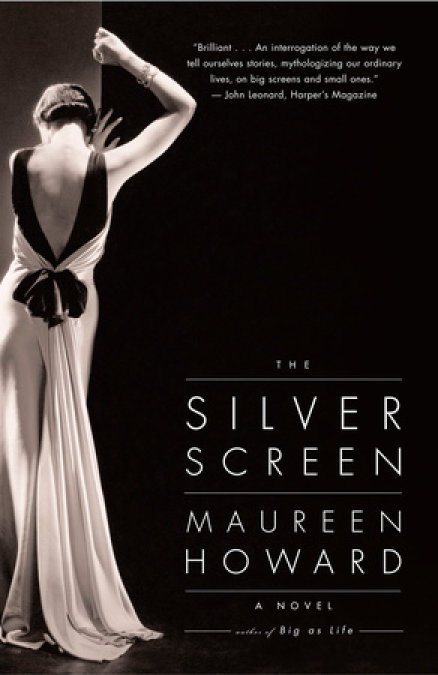

The Silver Screen

- eBook

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Maureen Howard deepens her inquiry into the meeting place of history and family in this stunning and accessible novel. Isabel Murphy renounced silent-film stardom to raise a family in Rhode Island. Now she is dead at 90 and her children are trying to break free of the lives she has dealt them. Joe, a Jesuit priest, has failed at love and the healing of souls. Stodgy Rita has found late happiness with a gangster who has turned state’s evidence. And Gemma, Isabel’s honorary child, has grown up to experience a strange celebrity as a photographer. A darkly comic story of guilt, love, and forgiveness, The Silver Screen is luminous in its intelligence and empathy.

Release date: July 26, 2005

Publisher: Penguin Books

Print pages: 256

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Silver Screen

Maureen Howard

Methinks we have largely mistaken this matter of Life and Death. Methinks that what they call my shadow here on earth is my true substance.

—Herman Melville, Moby-Dick; or, The Whale

Sea laps the shore. We need not know what shimmering sea, what pure white sand. Girls frolic— ten, twelve of them. A show, a game? Beach balls in the bright air. They catch and throw flip- wristed, and for no reason at all dash to a rickety wooden bleacher set up on the beach. Arranging themselves for a still shot, arms and legs flutter, won’t be tamed. Amusing pets, all pretty. Some have ribbons round their bobbed hair. Some wear brimless hats molded close to the head, a flirty curl or two escaping. Their bathing suits, belted or sashed, are striped, a few checkered in harlequin patterns. Silly girls laughing, smiling to beat the band. (The band, set to the side, an upright piano, clarinet, mandolin.)

The Bathing Beauties have been rehearsing. Now they romp to the twanging beat of the music, which drowns out the grind of the camera. Play ball, dash for the bleachers, pose in the jersey bathing suits that cling to their delicious bodies. The soft cotton maillot caresses their breasts and thighs. So concealing we find it, these seventy, eighty years later. Look again at the seductive wrapping on the package—bold stripes on the hip, molding of crotch, bouncing buns. See them— window dressing, background, chorus—naughty and nice, harmless girls. They stop, turn suddenly in mid-action. The clarinet bleeps to the end of a phrase.

“She’s a beaut!”

“Which one?”

“With the curly black hair.”

“Jeez, Mack, there’s five with curly black hair.”

“The one laughing at us,” says the man in the boater, squinting into the sun. “Girl with the cupcakes, that one.”

From a crude stab of his cigar in her direction the girl knows she is that one and crosses her hands on her breasts, a saint in mock supplication. Then a fellow in a floppy cap reaches for the buckle at her waist, tugs her out of the crowd of ten or twelve or thirteen pretty girls. He is wearing a linen jacket, sweat-stained at the armpits. The boss with the boater, cool in gray Palm Beach suit—vest, watch chain and all. These men might be lawyers, bankers, Chamber of Commerce—any town, any bright summer day.

“Step down,” the boater says to the pretty girl with the black curls. “Walk. What’s the hurry? Turn the head. Give me the eye.” She pulls a sultry pout, sashays slowly through the sand. “Peachy.” Then from the fellow sweltering in white linen, “What’s your name?”

In the brittle sunlight, her voice rings out mellow and clear, “I am Isabel Maher.”

She is given instructions. A palm tree and a cabana are set next to the bleachers.

“Take it again, girls.”

Pretty girls romp while the band struts its stuff to their tune. They make a run for the clattering wooden bleachers, pose for the picture while the vixen breaks away, away from the fun, and slowly, lips puckered, makes her way toward the famous clown who has been lolling all this time under a beach umbrella held aloft by a lackey. He is rumpled, waddling—so accomplished a fat fool in his antics, America laughs till it cries.

Chin up, Isabel Maher gives him the eye.

Father Joe in the Shadow Box

My mother thinks me wise. Let her believe it. Stooped with age, Bel cocks her head like a curious bird to meet my encouraging smile, the professional smile of a priest—hopeful, indulgent. The bold young woman who rents a house down the lane calls her the old lady. Each day I steal out of my boyhood bed, dress at dawn for the morning walk, my sister already fussing in the kitchen. It is Rita’s pleasure to re-create the pancakes and muffins of our childhood while I march smartly down the lane with the prop of my worn leather breviary, as though I might read the morning office, supplications and prayers committed to memory a half-century ago.

“Visiting the old lady?” a wisp of a girl in a scrap of bathing suit asked my first day home, still calling it home. She balanced awkwardly on the rim of a deck chair, greasing her thighs and belly to protect her pale flesh from the first rays of the sun. It promised to be a scorcher, the air heavy, humid.

“Visiting.” I passed quickly on, but not before a strap fell, disclosing the white hemisphere of her breast with its pole of brown nipple. For a moment I wished that I wore the Roman collar, not to disapprove the flaunting of her body, to scold her with a clerical look. She is not permitted in her cheery, childish voice to call my mother the old lady. Yet how true—Bel’s sparse white hair, swollen blue veins, odor of stale rose water—essence of old lady bent to the ground as though to seek out the comforts of the grave. But when would this girl frying in the sun have seen her? My mother is always at home now. If she tends a flower, throws crumbs to the birds, she cannot be spied on behind the tall privet hedge closing our house from the world. A house long guarded by our private ways.

It is my illusion that, set in our roles, my mother and her children will go on as we have forever. My visits to this hillock of New England which looks out to Narragansett Bay are the occasion for stories of the past repeated so often they might be told by the faded wallpaper or deadwood of kitchen table. Was it the hurricane of ’38 or tidal wave of ’54 swept our picket fence into the sea? The Irish setter or blind terrier wrestled the Christmas turkey off its platter? The hard winter of measles or mumps? Adrift in uncertainty, we prattle each day of my visit as though silence is forbidden us. We are sure of one thing. Our stories begin in this house—Bel in labor, clutching the bedpost while my father, who sold insurance against death and disaster, changed a flat tire on the Ford. The past had no preface to the blistering summer day on which, with the help of a neighbor, I was born to Isabel Murphy while her husband stood by with a spanner wrench in his good hand—his left arm, wounded in the Great War, hanging limp at his side.

•••

But I must take the giant step forward. I came round the hedge on this, the third day of my visit, tripped on the crumbling cement path. My sister was at the open door, still and speechless. “What?” I asked. The flesh around Rita’s eyes pale and soft, the defenseless look of the shortsighted without glasses. “What is it?”

The bulk of her blocked my way, though I saw past her to the stairs—to the mirror reflecting the empty hall above and a ray of sun with dust motes churning to no purpose. Finally, she stood aside, my little sister grown bottom-heavy as a giant pear. I knew that I must run upstairs, see myself for a fleeting moment—a gray-headed man with the high forehead that once defined me as brilliant. I must steal down the hall past the tidy room they keep as a shrine for my visits, past my sister’s virginal room with its stuffed panda propped on the bed, souvenir of some festive night in her youth, past the gleaming bathroom scoured clean of our bodily functions, past the hall window that frames our view of the sea, the sun on the water blinding this Summer day, flags rippling on the promenade. My desperate journey to the room where Bel lay, mouth in a slack smile, gaze strangely bright— looking at last upon her Maker.

The body still warm. With faint hope, I turned to Rita, who looked on from the hall, then came to the bed lightly with the tiptoe steps of a heavy woman defying gravity. We found no words for this dreaded occasion. I turned to my sister, knowing she often attended to the dead. With a sweep of her hand Rita drew our mother’s eyelids shut, then presented me with one of the mysteries of our childhood, the black leather box, the death kit of last rites that lived in a cupboard behind the sheets and towels of daily life. I made a stab at my priestly duties, turning down the coverlet to anoint the extremities of the body, the eyes and the mouth with holy oil, mumbling prayers half remembered. My mother lay straight in death, no longer bowed by the weight of years.

As I pulled the window shade, my eyes smarted at the glittering day, an unlikely setting for sorrow. Stunned, our silence heavy, prolonged. “A blessing,” I said at last, “to leave us in her sleep.” Rather too quickly, Rita surveyed our mother’s closet, pulling out a Sunday dress and dainty shoes for the body’s presentation. I had not forgotten that as a physical therapist my sister went from house to hovuse of the infirm and aged, the dying, though I had never seen her at her efficient work.

“She went peacefully,” I said. “Bel left us in the night.”

“Not at all. She called your name, but you were off on your morning stroll.”

“Called my name?”

“Jo-ee! Jo-ee!”

Rita attempting our mother’s two-noted bleat, her sweet clarion call reining me in when I wandered as a child. When my sister speaks up for herself—it is not often—her eyes blink behind thick glasses, her neck mottles with red splotches. “You didn’t wonder why she wasn’t up and about?”

For years I had not wondered at anything in that house. True, each day, as I headed out on my morning walk, I saw our mother perched on her kitchen stool already awaiting my return, when she presented her withered cheek for my kiss, eager for my every word.

“Now, then,” Rita said, “the arrangements.”

The arrangements were to carry us through the next days. Casket, flowers, mass, burial. Our mother was well over ninety, the date of her birth uncertain. Not a friend left to mourn her, but she was always a woman alone. More than a privet hedge grown beyond clipping set Bel apart from this town. At the wake, two women from the agency who assigned my sister the rounds of her practical mercy were in attendance, and a parade of ghosts from the past—the aged boys and girls we had gone to school with. All now strangers to me. Father, they say as I listen to tales of their children and grandchildren, their divorces and ailments. I can’t bear their deference. They are not curious about my work, the daily grind of a schoolteacher. These shuffling men I’d run bases with, coy housewives I’d kissed in the back seat of my father’s car had their scripted response to my black suit and the legend they will not give up on—that I had left them behind for the higher calling— though we sweated as one beast in the close living room with the television pushed out of the way for the casket.

Bel lay prettified in her white velvet nest. When my father died, she wrote to me. I buried Murph from the house. We do not rent a commercial parlor.

A sturdy woman with sleek black hair, many rings, bracelets, a costume all fringes and gauze, detached herself from the hushed sippers of Rita’s iced tea. “Just think,” she said, “your mother was toddling about before the First World War.” Boldly sipping a glass of whiskey, she held out a hand with scarlet nails, “Gemma Riccardi. You took me to the prom.”

“Gemma!” I was about to say something foolish, tell her she was lovely as ever, when the first noisy crackle preceded the shrieking trajectory of a rocket. Fireworks on the promenade. With our many arrangements, we’d lost track of the day. Night had descended on the Fourth of July.

“What a send-off.” Gemma’s laugh rumbled across the silent room. “Bel would have loved it.”

“The bombs bursting in air,” I sang.

We sang, Gemma and Joe: “O’er the la-aand of the free . . .”

And that is how Father Joseph Murphy, S.J., disgraced himself at his mother’s wake. But let me tell you, we had all turned to the open windows. Bottles of wine and the Irish were brought forth from the sideboard, plastic glasses handed round. Some of the old school chums were already out the door. The lane that runs by our house has always been the best vantage point from which to view the patriotic display, the burst of colors across the heavens in a spectacle of lights. Somehow I was to blame for this pleasure, had given my blessing to the breathless wonder of the mourners. The women from Rita’s agency of good works climbed up on the high hood of their recreational vehicle, but I noticed that my sister was not with us. I ran to the house thinking she kept solitary vigil with the dead.

My mother lay alone in the parlor with abandoned sandwiches and crumpled napkins, at peace in her repose. All the embalmer’s art could not mar the beauty of ivory brow, strong sweep of jaw, defiant tilt of her delicate chin. Gone, gone away, recalling the times when she stood apart, dreamy and distant—even in sunlight—the laundry basket held aloft as if our socks and underwear flattened by the mangle were bounty she presented to her gods; or she might walk from us to touch the bark of a tree, kneel to a powdery anthill, caress a shard of beach glass, a rubbery frond of seaweed. Come back—I wanted to cry in those moments of childish despair—back to me. She never heard. When she turned with a blink of her agate eyes, turned to us—her children, her husband—it seemed she must remember to step through the frame, breathe in our everyday air. Carapace of old lady, where did you go? Mysterious in her coffin as the iridescent shell of a dung beetle in a museum case, scarab of the redemptive afterlife. That’s the embroidery of memory. I am only certain that I stood alone mopping my brow in the dreadful heat, punishing myself with the final distance of her death, when the phone rang.

The phone rang in the kitchen. A great pity I picked up. Rita chatting with a man.

“They’ll soon be gone,” she said.

“Not soon enough.”

Vulgar endearments—pet names, wet kisses.

“Sitting on your bed?” the man asked, and in the husky whisper of seduction began an intimate scan of the washstand, marble-top bureau, the looming wardrobe and collection of girlish trifles which adorn my sister’s room. The stuffed panda not excluded from his prurient tour.

Apocalyptic finale to the fireworks. Burst upon burst of hosannas. It was then Rita told this fellow of the unlikely scene. His guttural laugh. Well, who would believe it?

“And the holy father?”

“He’s out there with the rest.”

“Don’t call me,” he said. “You have the instructions.”

“It’s you shouldn’t call me.”

Ever so softly I lay the receiver in its cradle and returned to the casket, head bowed as if in prayer. Well, I said, here are your precious children—a fraud and a sneak. God knows it’s not your fault. For a moment I wanted to laugh at Rita’s kisses, as we laughed gently at her failed projects— baking, knitting—but the bitter scrape of her words was a harsh note never heard. The mourners, shuffling with shame, turned to the house, looking to say a last word to the bereaved, and there was Rita hustling downstairs, out the front door to receive their final condolences. In the distance a band played a Sousa march, the one we sang when we were kids—Be kind to your web-footed friends. For a duck may be somebody’s mother.

Only Gemma Riccardi poked her head in the door, bracelets jangling, to say in a sodden slur, “Schorry, so schorry.”

My lips were sealed. I said nothing to my sister as we tidied the parlor, nothing of the treachery I’d overheard.

Rita said, “Wasn’t it awful about the fireworks? And you with that Gemma Riccardi?”

Meaning awful of me to make light upon this solemn occasion.

“Bel would have . . .” I did not finish the thought that our mother delighted in theatrical hoopla, and cut back to the days when my sister and I had something on each other, might tattle, or not tattle, in a childish power play. And so we moved about the rooms in silence, discarding the rubbish, Rita devouring the sandwiches, crusts curling in the heat. Speaking of my sister, my mother often said, You must befriend her. Knowing her daughter was destined to be unloved, she had used that cool word. Befriend this simple soul.

We parted with a swift kiss at the bottom of the stairs, and as I turned back it seemed our mother smiled on us with a tweak of her lips, pretend animation, like the trick moves of a flip book. As I settled to the night watch, my thoughts were not of the past with its safe fragments of memory, but of my sister’s betrayal. We had counted on Rita being simple. The verbal dalliance I had spied on clotted in my throat, foreign matter I could neither swallow nor expel. I’d not said a word, thinking that this night was Bel’s show—no calling my sister back to exact a confession. And what might I say, my fury cloaked in pastoral indulgence? That I feared her moving beyond the emotions of a dutiful daughter and the narrow routines of her life. Our mother gone away this time for good, yet I felt that she might speak, Bel’s gentle commands directing us still, that her children must be as she ordained us—priest and spinster. We are that, Bel, your spoiled fruit. Not long into the night watch, a dread came over me. I was to officiate at the Mass of the Dead. Deserting my post, I went up to my room to prep with a tattered missal left on the shelf with my Boy Scout Handbook, Caesar’s Gallic Wars and The Sultan of Swat, a life of George Herman Ruth written when the Babe first slammed sixty. And Ovid. How I loved the cheap edition given to me by my Latin teacher, an old Yankee who drilled us in declensions, who saw in me the one student who might go on with the dead language he was killing off. Delaying my sorrowful duty, I turned through the flaking pages. There they all were, gods and goddesses disporting themselves in stiff translation, tricking each other, exacting revenge. As an earthbound boy, I understood the creation of their world from lumpy matter and discordant atoms to be fantastic, no more than comic-book tales. This room with its white iron bed was a wet dream of innocence. Oh, I’d been such a good son—the mere recall of my mother’s expectations shamed me, that I would please her—training for the higher life. Lightly said, dead serious—the higher life, that phrase of her invention when I was about to leave home for the seminary. I believe she convinced my father somewhere back in time, the time of my baseball triumphs, of spelling-bee victories and grammar school orations, that I was not meant for this world. Or back in kindergarten, when Bel’s hand caressed my head, a gesture of sanctified selection drawing me apart in the playground from the play of ordinary boys, Madonna and Child of the Crosswalk at Pleasant and Elm. Little sister trailing behind. A miracle I was not mocked as Mamma’s boy. Her grace, her authority was my protection. Or I was the miracle, wasn’t that the ticket, Bel? The love child conceived in virtue, nothing off base about it, just to say that, growing up, I was always in training. In your comforting marriage to Tim Murphy, we were a team.

When I was first a young Jesuit portioned out to a parish when the regulars, as we called them, were on vacation, men and women spilled every sinful thought and deed to a green priest concealed in the confessional. How many times, I would ask, did you steal, lie, perjure, sodomize, pleasure yourself and, probing for the old reliable, how often commit adultery? As though I had knowledge of lust, I advised against the occasions for sin. I absolved foolish pranks of children, spiteful thoughts of old women, knowing they could not see my faint smile behind the net screen; still, as clerk of the court, I demanded an accounting. Often, I barely mumbled the formula for forgiveness, the first hint that I was unfit for the job. My job for many years: not listening in the shadow box of the confessional, but solving simple algebraic problems in the humming fluorescent light of a schoolroom.

But in the morning, I must assume my pastoral role. Flipping the gilt-edged pages of my missal, I came upon “Sequence to be said in all Requiem Masses”:

Day of Wrath, O Day of mourning,

Lo, the world in ashes burning—

Seer and Sybil gave the warning. . . .

Wondering who to blame for such doggerel. Seer and Sybil? Hangover from Greek mythology, embellishment of some prelate schooled as I was in the classics, out of touch with common speech of the faithful departed. My old black book was outdated. I must choose each word to memorialize Isabel Maher Murphy, whose life was—well—remarkable, though uneventful as I knew it. My last pastoral role, sharing the daily life of peasants in Salvador, so if I tripped up on the liturgy of Lesson and Tract, I trusted my mistakes would be taken for grief.

•••

Rita wore the prescribed black as they carried our mother out the front path to the hearse, though I saw that she had set out holiday clothes on her bed, the proverbial riot of color in splashy yellow and red costumes, a pair of enormous checkered pants and the straw hat of a coolie. I hovered at the door of her room while she stuffed diaphanous scarves and silver sandals into a tote bag with the legend Ambrosia—the Heavenly Spring Water.

Rita with the new rough edge to her words, “I’ve paid my dues, Joe.”

True enough. It was then, while the undertaker’s men waited for the grieving family, that she told me of the Portuguese fisherman who was to spirit her off to retirement in everlasting sun, of his children glad to be rid of him, of a bright future by the pool, their cruises and card games so long delayed, all told with a belligerent sniff. They were to be off on their adventure before the flowers wilted on our mother’s grave. A truly practical nurse, my sister had tied up with the husband of a woman who did not survive her efficient care. And Rita knew that I knew, the way we knew each other’s scams when we were children, that every word was a lie, her neck now blotched vermilion.

“The car is waiting.” I escorted her briskly downstairs. In the limousine, my sister’s heaving sobs did not alarm the driver, who turned to us professionally with a box of Kleenex.

“Paid with my life, Joe. You know it.”

“Save it,” I said, believing she cried for herself, not wanting, as we followed slowly behind the hearse, to hear her inappropriate story. If this is my confession, then let me say it was a sin not to hear her out, to award this last day to Bel untainted by our needs, Bel, who paid with her life— whatever that means—in giving herself to us. The comfort of our hired car that came with the arrangements was no comfort at all. I took Rita’s hand in mine, feeling it my duty, and discovered the gold ring on her finger. It looked a gaudy affair. “You will have to wait by the coffin till I’m vested.”

“Getting into your livery, Father Joe?”

We had laughed at that one with Bel. Irreverence fell flat in the cool of the limo. My sister now placed a black veil on her scrambled gray curls, turned to me with the shadowed face of celebrated widows costumed for public mourning.

“Rita!” I spoke her name sharply, my reprimand a mix of pity and anger at her costumed grief. She did not get my meaning.

My little sister is sixty-eight. I am seventy-one—blood pressure controlled by medication, heart off- beat in a rambunctious rhythm of its own. I pee maybe four, five times in the night. My father, the insurance salesman, would not issue a policy on my life. It’s all a risky business—he died on a Sunday afternoon watching the Red Sox wallop the Yankees, therefore died happy, but that was our solace in the midst of bereavement. Their bereavement, Rita’s and my mother’s. I was in a tropical country sweating the booze out of my body each day while the poor, discovering their dignity, learned to tell their stories. At times I taught the children old-style to add and subtract, scratch the alphabet in sun-baked earth, never to pray.

Rita and I knew little of each other, only the tangle of old yarns—Dad shooting squirrels in the attic, Mom winning the Buick in the Holy Name lottery. Hidden behind a scrim of anecdotes, we discounted the present. When I returned to the States and resumed my visits, we played our simple parts. I now believe our mutual deception was cynical. Muffins, pancakes, bloody steaks I loved, the glass of non-alcoholic wine, Rita’s fat-girl laughter at my mildly profane jokes. And my mother, who had been such a stunner driving about town in her big-assed Buick, ready for any diversion, had slowly, slowly retreated to life behind the barricade of our hedge grown thick and tall. Bel awaited my school holidays when I took the train from Grand Central, the bus from Providence, and walked home from town. There were times when I thought to turn back, that in honesty I could not go another block through the neighborhood streets, head into our lane with the houses I once knew so well—the Dunns’ sloping breezeway, the Pinchots’ carport with its artistic display of hub caps, the Mangiones’ cast-cement lions guarding their patch of lawn. But as always, I found my way to the door which my mother left unlatched. There she waited, dressed in her finest, hair pinned back from her face radiant with her belief in me. Lord, as the fella said, help my disbelief.

Why turn back to Rita’s desperate laughter or, for that matter, her sobs in the comfort of the air- conditioned limousine? No turning back to my father, Tim Murphy, watching the Yaz field a line drive for the Red Sox in a near-perfect game. I never knew if he knew the score or passed away at the seventh-inning stretch with the bottle of Bud held firm in his good hand. Both of our parents, departing this life without the pain of departure, as though they had recited the Prayer for a Happy Death, were beckoned at the fateful moment, and simply obeyed. Oh, my mother called out my name, but I was gone more than the quarter mile down the lane, long gone. Joey, Joe Murphy, will not come again to her weathered house by the sea.

Day of the funeral there was no one—that is, no one but Gemma Riccardi in her dress-up and a young woman I could not place who sat in the back of the church, perhaps a stray. I had managed the Mass of the Dead with the help of a young parish priest confused by my bumbling with the sacred apparatus of chalice and paten. I blessed the mahogany coffin for a very old lady, its waterproof lining chosen some months ago by her daughter, who had long awaited this day. I had prepared a few words beyond the liturgy, pieties about Bel as mother and wife, true enough, and truly felt, yet insufficient. Then I spoke to my sister and Gemma, the girl my mother took under her wing when we were children, now a strange woman with coal-black hair, her large body hung with exotic silks and bangles. Just the three of us, I said, to remember Isabel Maher of silent movies which we seldom spoke of. (During the night I’d done my homework, discarded Sybil and Seer for Ecclesiastes, a line to recall that closed book of my mother’s life.) Better a handful of silence than a handful of toil and a striving after the wind. She left the glitter and bright lights, came home, I said in the heavy candle-wax air, to marry Tim Murphy, and so we must feel we were chosen. Bel’s role was to be our star. (Rita’s response to my words hidden by the black veil.) What comes to mind this morning, more than her love and endurance, more than all she witnessed in the length of her years, is Bel’s excursions. (Gemma mopping her eyes.) Just the three of us kids in the Buick. The year, if I remember correctly, was 1943. Excursions, that was her name for the pleasure trips she fashioned to places of note. She drew a circle on the map and marked what grand sights we might see and still get home in time for supper.

Then I recalled our transgression, that we skipped school for the day, named the Arcade in Providence and the Narragansett Pier as our destinations, that we crossed to alien territory in Massachusetts and Connecticut. What did she hope for us? That she might impart her spirit of adventure. Perhaps I’d come upon the excursions to escape the mystery of our parents’ marriage or the hard truth of my mother’s domestic confinement. As I stood over the expensive box that held her body, I figured for the first time that in these outings with three kids, sharing our treats of frankforts and soda pop, Bel was the truant. I did not say it. Better a handful of silence. I let my eulogy lapse into a prescribed prayer. In the h

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...