- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

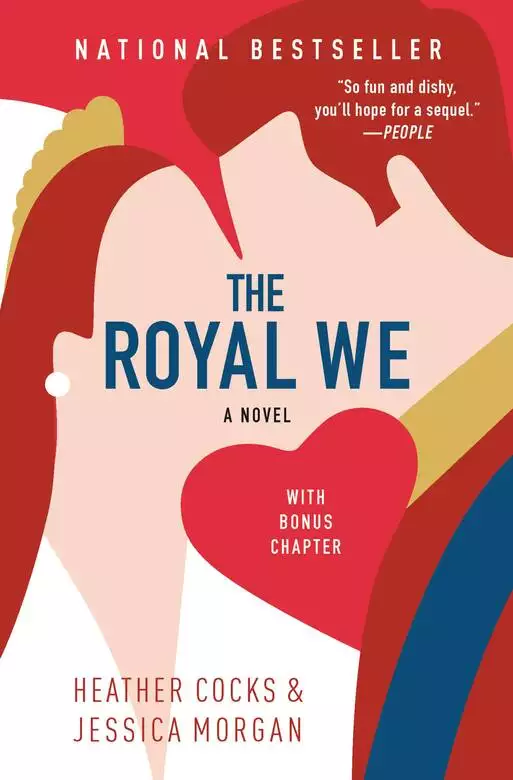

The Washington Post and USA Today Bestseller

American Rebecca Porter was never one for fairy tales. Her twin sister, Lacey, has always been the romantic who fantasized about glamour and royalty, fame and fortune. Yet it's Bex who seeks adventure at Oxford and finds herself living down the hall from Prince Nicholas, Great Britain's future king. And when Bex can't resist falling for Nick, the person behind the prince, it propels her into a world she did not expect to inhabit, under a spotlight she is not prepared to face.

Dating Nick immerses Bex in ritzy society, dazzling ski trips, and dinners at Kensington Palace with him and his charming, troublesome brother, Freddie. But the relationship also comes with unimaginable baggage: hysterical tabloids, Nick's sparkling and far more suitable ex-girlfriends, and a royal family whose private life is much thornier and more tragic than anyone on the outside knows. The pressures are almost too much to bear, as Bex struggles to reconcile the man she loves with the monarch he's fated to become.

Which is how she gets into trouble.

Now, on the eve of the wedding of the century, Bex is faced with whether everything she's sacrificed for love-her career, her home, her family, maybe even herself-will have been for nothing.

Release date: April 7, 2015

Publisher: Grand Central Publishing

Print pages: 252

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Close

The Royal We

Heather Cocks

Prologue

I don’t know what to do.

The calls and texts are starting to pile up, relentless and suffocating. I’m afraid of what will happen if I don’t give him what he wants, and I’m afraid of what will happen if I do. The TV isn’t soothing my nerves, given that global hysteria over my impending wedding is the lead story on every channel. I can’t lose myself in a book, because the only ones in my hotel room are dusty old historical tomes, and there are few things less reassuring right now than reading up on the spotty fidelity (and sobriety) of Nick’s ancestors. And my sister is of no comfort to me. Not anymore. I’m officially in this alone. With every jolt of my cell phone, I feel more and more like the proverbial chaos theory butterfly from high school science—the one that flutters its wings in one place and causes a tsunami somewhere else. I always felt bad for that butterfly, being blamed for a meteorological mess just for doing what nature ingrains in it to do. Now I want to step on the damn thing for flapping around like a fool. Because I am that butterfly. That is, assuming I’m not the tsunami.

If only I were home, so I could freak out on familiar territory. But instead I’m stuck at The Goring in ritzy Belgravia, or Bexingham Palace, as the press calls it. Her Majesty has never met a space nor a situation on which she didn’t impose her will, so Queen Eleanor’s army of decorators dropped six figures to renovate the penthouse into bridal headquarters, evicting all The Goring’s furnishings—although they thoughtfully left the life-size portrait of Queen Victoria I that sits, unnervingly, right inside the shower behind thick safety glass—and replacing them with priceless accent tables and figurines, ornate and uncomfortable sofas, landscape portraits pretending to be out for cleaning from the National Gallery, and a grand piano littered with portraits of the Lyons ancestors who will become my family tomorrow. It is a parade of mustache wax and sadness, only mildly mitigated by the official photo of Nick and me. I love that picture, which is lucky, because it’s for sale the world over on thimbles, wastebaskets, tea towels, paper dolls, condom boxes, and—my favorite—actual condoms. If she were cheekier, Her Majesty would have put those items on the piano. As it stands, I’ve never heard any of the senior royals even say the word condom, although I suspect Eleanor would pronounce it like my own grandmother did: as if it’s the nickname of the local cad who scandalizes all the gossips in the retirement village. (“Did you see Con Dom at the grocery store? He was buying six boxes of wine and a frozen burrito. What does it mean?”)

Suddenly, from across the room, a red beaded frame in the collection catches my eye. I could swear it wasn’t there yesterday, and when I move closer, the sight of the photo inside gives me the chills. The press would salivate over it, which is precisely why I thought it was locked away in Mom’s wall safe, behind a yard-sale portrait of a rich-looking lady whom she pretends is a distant moneyed aunt from the continent. In the picture, which Dad took on a family trip to Disney World, Lacey and I are eight. She is clutching Cinderella’s hand with the same urgent glee you see in people waiting to hear if they’re about to come on down on The Price Is Right, and wears a poufy pink gown and a tiara on her golden ringlets. I am a careful half step away, in shorts and Tevas, attempting a smile that fails to conceal my boredom. My dreams back then were to swim the individual medley at the Olympics, or play Major League Baseball; the Disney version of happily ever after didn’t impress me, and you can see that all over my face, as clear as the adoration in Lacey’s eyes. It is the perfect photo of mismatched twins, but beyond that, it’s deeply ironic given who Lacey and I have become, which is exactly why I asked Mom to hide it. I look like I hate Cinderella, yet now, to the world, I am Cinderella. The headline writes itself, and so does the karmic warning: Be careful what you pointedly don’t wish for, because one day you might find yourself getting armpit Botox to avoid headlines like THE DUCHESS OF SWEATSHIRE. Dragging this photo out reeks of Lacey, and ordinarily, I’d have assumed she did it for a laugh. But today it feels like a threat. When my phone vibrates again, I half expect it to be her.

It’s not.

YOU CAN’T PRETEND NOTHING HAPPENED.

That much is abundantly clear. I just wish I had more time to think. Tomorrow morning, I am supposed to walk Westminster Abbey’s three-hundred-foot aisle, wearing the biggest skirt of my life—the gown has its own room at The Goring—and pledge myself for eternity to Prince Nicholas of Wales, a king-in-waiting. I cannot tremble. I cannot twitch, even if Gaz weeps that high-pitched wail of his. I cannot disappoint, I cannot bend, I cannot break, because two billion people will be watching (one of whom might even be that tired, retired Cinderella, who hopefully won’t recognize the kid who once regarded her with so much skepticism). So, no, I can’t pretend nothing happened. But if I acknowledge it out loud…

My phone lights up and I jump so violently that I almost drop it.

“Morning, love,” my mother says, in the England-via-Iowa accent she’s adopted. The press has nicknamed her Fancy Nancy. “I’m actually looking for Lacey. Is she there?”

I snort.

“Bex, no swining,” Mom says, parroting a pun of Dad’s.

“The Daily Mail says she got a spray tan for three hours yesterday. Wherever she is, I’m sure she’s happy. And orange.”

“Cut it out, Rebecca.” That was a hundred percent American. My mother’s faux accent always disappears when she’s irritated. “You’re getting married tomorrow. Do your twin thing and apologize and fix it.”

Irritation strains my voice. “I can’t apologize if I wasn’t wrong.”

And I wasn’t, not about that. I’m squarely in the wrong now—Mom has no idea—but then again, so is Lacey, and I can’t always be the one to lay down my sword to keep the peace. Especially not when I’m under attack.

I hear a fumbling at the suite’s front door. “Mom, I have to go. The Bex Brigade is here.”

Within seconds the room is swarmed by stylists, seamstresses, security officers, and all manner of other Lyons operatives. I shove the blackmail-worthy photo deep behind a seat cushion. Out of sight, out of mind.

“Cheers, Bex, you look like microwaved shite,” chirps my personal secretary, Cilla.

“I’m just overtired.” It’s technically not a lie. “Actually, is it okay if I take a few more minutes?”

Cilla cocks an eyebrow, then nods briskly and hands me my usual stack of newspapers and tabloids. I excuse myself to my bedroom and fan them out on the paisley comforter. I’m everywhere. The Guardian’s front-page piece, GREAT BEXPECTATIONS, is about international wedding fever. WE’RE SO BEXCITED!, screeches The Sun, before handicapping what I’ll wear down the aisle. HALF HUMAN HALF CHEESE WHEEL BORN TO LEICESTER COUPLE: Mother Weeps, “I Always Knew We’d Brie Blessed,” claims the Daily Star, dwarfing a blurb about whether I’d forced Nick to get hair plugs. The goofy photo they picked to illustrate this makes me smile. I haven’t slept beside Nick all week, and I miss him—his bedhead, the snores that could dwarf a thunderstorm, the way he can’t fall asleep unless we are touching. I even miss that he always burns the first waffle he toasts. I fell in love with a person, not a prince; the rest is just circumstance.

The problem is, it can be hard to remember that. Which is how I got myself into trouble.

A text comes through: TIME IS RUNNING OUT.

With a thump Lacey bursts into my room, atypically ashen considering how much money she spends never to be that color. I am so startled to see her that I can only blink as she slams the door and leans breathlessly against it. She feels so far away from me even though she’s standing right here.

“I did something,” Lacey begins, not quite making eye contact.

So did I, but of course she already knows that. Once upon a time, I would ask for her help, us against the world. Now, it’s her against me, and the world probably will pick her side.

I might be Cinderella today, but I dread who they’ll think I am tomorrow. I guess it depends on what I do next.

Chapter One

If you believe my unauthorized biography, The Bexicon, Nick fell in love with me at a pub on my first night at Oxford, and angels burst into song while rose petals fell from the sky:

The King’s Arms was packed with reveling youngsters hungry for one last bit of mischief before the new term. But Rebecca Porter radiated a halo of confidence and serenity, modestly leaning against the back wall, holding a ladylike half-pint she would only sip twice. “Bex was never a drinker,” a friend says. “She knew how to have a laugh, but you’d never find her dancing on a table to impress people.” Indeed, the more he watched the seraphic American student—diffident and humble in sweetly vintage clothes surely destined for the Victoria and Albert Museum—the more Nicholas knew he had to claim her. He had found someone special. He had found his queen.

Complete fiction. In fact, the whole book is so inaccurately gushy that I often wonder if the author is on Queen Eleanor’s payroll. The week it was published, we were in Spain at what everyone refers to as “Prince Richard’s cabin”—Nick’s father’s coastal spread with fourteen bedrooms and its own vanity winery—and Nick laughed so raucously when I read this section aloud that his aunt Agatha, a full fifty yards away, jumped and dropped her gin and tonic.

“Are you sure it doesn’t say, ‘You’d never not find her dancing on a table’?” he’d asked. “Isn’t that more accurate?”

“I am not table dancing right now.”

“Pity,” he grinned, raising his scotch to me.

“There’s still time,” Nick’s younger brother, Freddie, had said from his deck chair. “In fact, Agatha over there could use some pointers. I don’t think she’s had any fun since she married Awful Julian.”

In reality, Agatha does occasionally have fun, though usually only when needling her boozy bounder of a husband about how his ancient father refuses to die (and thus hand down his viscountcy). Nick and I never went to The King’s Arms, because pubs with royal nomenclature make him self-conscious. And when fate pushed a prince into my path, my hair was dirty, I smelled like the canned air of the Virgin Atlantic plane that had deposited me at Heathrow, and my jeans and sailor-striped T-shirt could only be classified as vintage because of their extreme age. Aurelia Maupassant, author of The Bexicon, would be crushed.

* * *

When we were small, Lacey and I would sneak flashlights under the covers to read aloud from books about plucky British kids, their boarding-school hijinks, and their ill-fated wartime love affairs. Lacey was obsessed with the swoony kissing parts, but what stuck with me was a different kind of romanticism—the sense of epic sprawl compressed onto a small island that positively burst with art, antiquities, and history hiding in plain sight. I itched to inhale it, to live it, to sketch it all. So when I found out Cornell could do an exchange with the University of Oxford, I applied about five minutes later. Oxford didn’t sound as overwhelming as London, yet every photo I saw of its glorious collage of buildings—never quite new, so much as old, older, and oldest—promised it would be an artist’s dream. The tour guides tell you to try every door you find because it just might open, and it feels true; there are still quaintly cobbled streets with perfect, petite gardens behind wrought iron gates, and its picturesque nooks and crannies all but vibrate with centuries of secrets waiting to be unearthed. Its mystery, its age, its textures…Oxford is in all ways the opposite of Muscatine, my rural Iowa hometown (or even the bucolic North Atlantic beauty of Cornell), and for me it was perfect. I didn’t come to England to fall in love with anything but England. I didn’t come to get married. I came to draw. I came to be inspired. I came for adventure.

I suppose I got it.

Oxford’s student body trickles in as many as two weeks before the beginning of the new term—the crew team needs to adjust its sleep cycle just as much as a jet-lagged American does—so I arrived late on a mid-September afternoon with about ten days to unpack, recalibrate, and explore. The academic colleges there function like mini-universities under the Oxford umbrella—as if my old Cornell dorm also had its own professors and classrooms—and I had been accepted to live and study in one called Pembroke. It was smaller than some of the other thirty-seven dotted around town, and its lack of notoriety may directly correlate to being right across the street from the imposing, absurdly famous Christ Church college. We lived in its shadows—literally, come late afternoon—and during my year there, when the omnipresent red tour bus stopped to point out the historic building that was in the Harry Potter movies and observes its own time zone, the guide wouldn’t even so much as glance across the street. Now, Pembroke is the main stop on the Royal Romance tour, which leaves from the train station every forty-five minutes. According to Gaz, who took it six months ago on a lark, it’s almost as fictional as The Bexicon. He cried anyway.

A light drizzle was falling that first day as I hauled two giant suitcases, a laptop bag, and my purse up the cobblestone road toward Pembroke’s main entrance. My suitcase kept catching a wheel and flipping over, twisting my wrist and causing my shoulder bags to whack me in the leg; by the time I reached the door, I was panting and had slim rivulets of rain dribbling down my nose. I rang twice for the porter and cursed loudly when no one answered. It had been a plane, train, and automobile odyssey to get me from Des Moines to that front stoop. I was cold, wet, and exhausted, and, from what I could tell, my deodorant had not stood up to the journey.

I buzzed again. The door opened and a tall, sandy-haired guy poked out his head.

“Need a hand?”

“Oh, please. Yes. Thank you.”

He held up a stern palm. “Wait, how do I know you’re supposed to be here? I heard you swearing. Foul language doesn’t befit an Oxford student.”

I stammered an apology until I noticed he was grinning.

“I’m joking,” he said. “You’re Rebecca. I was told you’d be coming.” He widened the door and came through to get my bags. “The porter is very protective of his tea break, so I said I’d sit in and look out for you.”

“And you let me hang out here in the rain just for fun? Is that behavior befitting an Oxford student?” I said, stepping inside, cozy and warm after the rain.

“I may have been engaged in an in-depth study of REM sleep.” He shrugged winningly. “I’ve had two pints already and they make me so tired. Besides, I couldn’t have guessed you’d show up without an umbrella. That’s like going to the Bahamas without a bathing suit.” He hoisted up my bags. “Follow me.”

We trudged up the winding dark wood stairs, past stately oil paintings that looked so rustic they had to be originals, and blank-eyed portraits of alumni and monarchs.

“Which one is he?” I pointed to a man with a square jaw and a beard as thin as he was fat.

“That’s King Albert. Victoria the First’s grandson. Early nineteen-hundreds.”

“I feel like he’s staring right through me,” I said, shivering involuntarily as we wound our way up to the third floor. “He has kind of a homicidal face. Or is that just syphilis making him insane? British monarchs do love their syphilis.”

“A prerequisite of the job,” he agreed.

I snorted, at which he shot me a startled but amused glance before I followed him into a slender hallway, domed with carved beams and lit beguilingly with candle-shaped sconces. We passed six doors—three on each side—and stopped outside the last one on the left.

“Here you go,” he said, digging in the pocket of his jeans and then handing me a key. “Stop by the porter later and he’ll give you a full set. And come join us in the JCR, if you’re so inclined.” He gave me a crisp nod. “Welcome to Oxford.”

He was gone before my numbed mind got off a thank-you, much less decoded that acronym. I fought a head-splitting yawn and fumbled with the key—right as the door opposite mine flew open and an auburn-haired girl shot out of it and grabbed my hand.

“I see you’ve met him, then,” she said, in an accent I later learned was Yorkshire. “What d’you think? Rather nice for a guy whose face will be all over our money in fifty years.” She smacked her forehead. “Oi, I’m a dolt. Sorry. I’m Cilla.”

“Rebecca,” I said, blinking hard. “And are you telling me that was…?”

“Nick, yes,” she said. “Or rather, ‘Prince Nicholas of Wales.’” She made the air quotes with four fingers whose nail polish was in various stages of peeling. “He’s not insufferable about the title, thank God.” She peered at my glazed eyes. “Didn’t you recognize him?”

That I hadn’t was laughable (he still teases me that it’s treasonous not to tip your royal baggage handler). Lacey subscribed to every celebrity weekly in existence—she delighted in reading bits of them to me once she’d finished her homework, usually while I was still trying to do mine—and Nick had appeared in them all. But in person he lacked the macho sheen the media always tried to give him, and I don’t care who you are or how many times your twin has told you to practice constant vigilance: You still don’t expect the so-called Heartthrob Heir to be your glorified bellhop.

“So the future sovereign just heard me accuse his relative of having syphilis?” I asked faintly.

“Oh, that’s a good one,” Cilla said. “But don’t worry. Gaz once threw up all over him and Nick didn’t even bat an eyelash, and that’s saying something because Gaz eats a lot and there were loads of chunks.” She grabbed a bag and barged past me into my room.

I finagled my other suitcase through the doorway and took in my new home. There was an irony in coming all the way to Oxford to find that my room resembled the ones in every dorm in America: a twin bed with a metal bedframe, a radiator under the window, and a desk with a hutch that looked like it came from an office supply warehouse.

Cilla nodded at a heap in the corner. “I filched some of Ceres’s things that she didn’t take when she left,” she said. “A rug, some throw pillows. Whatever might make it less awful in here. We can decorate later, though. First let’s get you to the bar for a welcome drink.”

“Shouldn’t I change?” I asked, wondering if I smelled bad to people whose noses weren’t as close to me as my own was.

Cilla waved at her torn jeans, creased boots, and woolly sweater. “Yes, we stand on formality here at Pembroke,” she intoned. “Actually, Ceres would put on high heels and lipstick to go down and get the mail. If you’re going to take that long, I’ll just meet you downstairs.”

I shook my head. “Can’t walk in heels and never met a lipstick I didn’t get on my teeth.”

Cilla beamed broadly. “We’ll get on splendidly, then, Rebecca.”

“Bex. Please.”

“Okay, Bex. Get on with it already. It’s been ten whole minutes since my last pint.”

* * *

It turned out the bar was the JCR—a dim undergraduate common area that looked cramped thanks to the jumble stuffed into it: mismatched chairs and chipped tables; a haphazardly hung flat-screen showing soccer highlights; and a substantial but inexpensive beer and booze collection, stocked by that year’s Bar Tsar (his elaborately framed photo hung on the wall). Even with the haze of cigarette smoke hanging in the air, it was easy to spot Nick because at least half the room was ogling him, and I had only to follow the stares. He was perched on a stool in a snug corner, relaxed and quiet, with two guys and a punky girl who did not wear her pink hair with much authority. Cilla steered me through the crowd right in their direction. She may have been small, but she was solid, efficiently built, and clearly not to be trifled with, because people parted for her as if by magic.

“These are more of the people in our corridor,” she said when she reached Nick’s corner. “Everyone, this is Bex, just in from America.”

One of them bounced to his feet so fast he almost knocked over the table. He had a kind face, bulbous nose, freckles, and a thick tuffet of orange-red hair—rather like Ron Weasley, but with scruff, and a round, compact belly that was either the product of a lot of lager, or his (ineffective) attempts to draw in enough air to appear taller than five foot six. Possibly both.

“Brilliant,” he said. “I’m Gaz. I expect Cilla’s told you all about me.”

“Just the vomity bits,” Cilla said.

Gaz grinned even wider. “That’s about all of it.”

A bespectacled dark-haired guy rose to his feet. “Please, sit. I’ll get drinks,” he said, gesturing to the threadbare, oversize chair he’d just vacated, and pulling out folded bills that were tucked into his back pocket with the same precision as the plaid collared shirt tucked into his jeans.

“That wonderful person with the fat wad of cash is Clive,” Gaz said. “And this young lady with the shirt that looks like she made it out of tea towels is Joss.”

“And I did make it out of tea towels,” Joss said, appraising me as Cilla and I squeezed into Clive’s empty seat. “Ceres was my fit model, but you’ll do nicely. Built just like her. Tall, no boobs.”

“Finally, being flat chested is an advantage,” I said. “My twin sister will be astonished.”

“Oooh, twins, eh?” Gaz said, wiggling his eyebrows.

“Get off it,” Cilla scoffed. “Gaz thinks he’s dead suave, but his father is a disgraced finance minister, so it’s more like dead broke. He still owes me thirty quid from last term.”

“I make up for it with piles of charm,” Gaz said. “And this bloke here,” he said, gesturing at Nick, “is…Steve.”

He adopted a deep, dramatic intonation, lingering on the word like it was a rich dessert to be savored. Nick buried his face in his beer, but the telltale bubbles gave away his laughter.

“Steve,” I echoed, trying on Gaz’s tone for size. “Sure. I can roll with that, Steve.”

Gaz slapped the table, which reverberated under his meaty hand. “You told her?”

“She’d have figured it out anyway,” Cilla said. “So take it down about three point sizes, please, Garamond.”

Clive was back and sliding the drinks onto the scarred coffee table. “‘Gaz’ is short for ‘Garamond,’ of the Fonty Garamonds,” he explained.

“As in, the actual font,” Joss piped up. “His grandfather invented it.”

“He’s mad as pants. Won’t even read anything in sans serif,” Gaz said. “Couldn’t he have invented something cooler to be named after? Like Garamond the Time-Traveling Motorbike, or Garamond the Lady-Killing Love Tonic?”

“I thought you were Garamond the Lady-Killing Love Tonic,” Cilla cracked.

“Well, as long as we’re talking stupid names,” he said irritably, “somebody tell me why we bother with Steve if none of you uses it.”

Nick rubbed the top of his head absently. “It’s not really supposed to fool anyone,” he said. “It’s more for if I’m caught in trouble or doing anything embarrassing.”

I met his eyes. “Embarrassing, like joking to a prince that all his relatives have an STD?”

“Exactly,” he said. “Although no one in polite society would actually do that.”

We smiled at each other.

Clive turned to me and pretended to study me deeply, as if my eyelashes were tea leaves he could read. “And you are…Rebecca Porter, almost twenty, from Iowa, father invented a sofa that employs a mini-fridge as a base—”

“Can you get us one?” Gaz interjected.

“…and you once got arrested for public indecency and trespassing because you accidentally tore off your trousers while climbing a barbed-wire fence,” Clive finished.

“I maintain it tried to climb me,” I quipped. “What else does my dossier say? Or do you just have ESP?”

“Of course there’s a dossier,” Gaz said, clapping a hand on Nick’s shoulder. “The Firm has to know who’s living twenty feet from the future of the bloodline.”

Nick’s discomfort was clear (one of his tells is that the tops of his ears start to vibrate—it’s the strangest thing). He drained the last of his pint. “While you lot are busy frightening Bex, I need to go say hello to some people.”

“Yes, right. Back to the grind.” Clive grinned, nodding toward a giggling, coquettish cluster of blondes across the way.

“There are probably worse fates,” Nick said. “I hear syphilis is a beast.”

He slipped off into the room, but didn’t make it far before he was waylaid by a cranky-looking patrician brunette in a high-collared blouse, who pulled him over to whisper in his ear.

Clive whacked Gaz on the arm. “You know he’s sensitive about the king stuff.”

“But it’s exciting!” Gaz argued. “Big intrigue. I’m very respectful.”

Cilla looked doubtful as Joss checked her cell phone. “I’m meeting Tank at the new punk bar over by the Ashmolean,” she said. “Anybody want to come?”

I glanced around for guidance. Cilla shook her head.

“Suit yourselves,” Joss said, leaving behind a quarter of a pint.

“Don’t mind if I do,” Gaz said brightly, reaching over and swigging it.

“Really, Gaz,” Cilla nagged. “You’ll be sweating lager next. My great-grandmother’s great-uncle Algernon had that happen when he was courting the Spanish infanta and—”

“Ah, yes, here we go again,” grunted Gaz.

“Cilla has more stories than Nick has stalkers,” Clive told me. “I’ve no clue if any of it’s true, but it’s bloody entertaining.”

“…and then of course she broke it off with him by trying to thrust a letter opener into his ear at her brother’s coronation,” Cilla was saying.

To better bark at him, Cilla clambered into the empty chair next to Gaz. Clive responded by settling into her old spot, smashed up next to me, our thighs touching. It wasn’t unpleasant. He was the Hollywood archetype of a sensitive yet smoldering Brit—wavy jet-black hair, strong jaw, and a voice that was smooth and husky all at once.

“So, Bex, what are you reading?”

“Reading?”

“Studying,” he clarified.

“It’s not in my file?”

Clive smiled. “We only got the juicy bits,” he said, sipping his drink and then licking the froth off his lip in a way that suggested he enjoyed my watching him do it.

“Well, theoretically I’m reading British history, toward my degree at home, but what I really want to do over here is draw,” I said. “I mostly work in pencils, and so much of the architecture here lends itself to dramatic gray and black areas. The arches, the carvings, the gargoyles…”

“Did I hear you say gargoyles?” Gaz interrupted. “That reminds me.” He pointed at the stern brunette. “That is our other floor-mate, Lady Beatrix Larchmont-Kent-Smythe. Otherwise known as Lady Bollocks, because of her initials, and also, she can be a bloody load of it.”

Lacey later described Bea as looking and acting exactly the way you would expect a Lady Beatrix Larchmont-Kent-Smythe to look and act. Her posture is as impeccable as her tailoring, she never loses her keys nor her cool nor so much as a chip from her manicure, and I believe she intentionally waxes her eyebrows so that she always appears to be raising them at you with deepest skepticism. Clive explained that Lady Bollocks was a lifelong friend of Nick’s family, and in fact, as we alternated pints and gin-filled highballs, he turned out to be full of tidbits: that Cilla’s ancestors lost their money in a lusty Downton Abbey–style scandal; that the girl tending bar once had a pop hit called “Fish and Chips” about a memorable weekend with a famous boy band; that two hundred people had money on whether Cilla and Gaz would sleep together or murder each other (he had a hundred pounds on them doing both); and that Joss’s continued enrollment was a mystery to everyone, because she rarely did anything except follow around her boyfriends and make clothes in her room, to the consternation of her pushy father—the Queen’s gynecologist.

“She’s a good enough sort, but we don’t see her much,” Clive said. “Her father requested she be on Nick’s floor, to light a fire under her or some such, and you don’t run afoul of a man who has such, er, sensitive personal information.”

“Keep your friends close, keep the secrets of the Royal Birth Canal closer,” I said.

“Something like that.” His hand brushed my leg again.

“And you’re the person everyone wants to sit next to at a wedding,” I said. “You’d have dirt on everyone in the room and at least two of their relatives.”

“Only two?” Clive feigned shock. “I do want to be a reporter, actually. I like learning about people. My brothers think it’s just an excuse for the fact that I’m afraid of having my ears torn off.” At my quizzical expression, he added, “They play rugby. Professionally. The biggest, thickest clods you’ve ever seen. Cauliflower ears and broken noses and all.”

“So how did you e

I don’t know what to do.

The calls and texts are starting to pile up, relentless and suffocating. I’m afraid of what will happen if I don’t give him what he wants, and I’m afraid of what will happen if I do. The TV isn’t soothing my nerves, given that global hysteria over my impending wedding is the lead story on every channel. I can’t lose myself in a book, because the only ones in my hotel room are dusty old historical tomes, and there are few things less reassuring right now than reading up on the spotty fidelity (and sobriety) of Nick’s ancestors. And my sister is of no comfort to me. Not anymore. I’m officially in this alone. With every jolt of my cell phone, I feel more and more like the proverbial chaos theory butterfly from high school science—the one that flutters its wings in one place and causes a tsunami somewhere else. I always felt bad for that butterfly, being blamed for a meteorological mess just for doing what nature ingrains in it to do. Now I want to step on the damn thing for flapping around like a fool. Because I am that butterfly. That is, assuming I’m not the tsunami.

If only I were home, so I could freak out on familiar territory. But instead I’m stuck at The Goring in ritzy Belgravia, or Bexingham Palace, as the press calls it. Her Majesty has never met a space nor a situation on which she didn’t impose her will, so Queen Eleanor’s army of decorators dropped six figures to renovate the penthouse into bridal headquarters, evicting all The Goring’s furnishings—although they thoughtfully left the life-size portrait of Queen Victoria I that sits, unnervingly, right inside the shower behind thick safety glass—and replacing them with priceless accent tables and figurines, ornate and uncomfortable sofas, landscape portraits pretending to be out for cleaning from the National Gallery, and a grand piano littered with portraits of the Lyons ancestors who will become my family tomorrow. It is a parade of mustache wax and sadness, only mildly mitigated by the official photo of Nick and me. I love that picture, which is lucky, because it’s for sale the world over on thimbles, wastebaskets, tea towels, paper dolls, condom boxes, and—my favorite—actual condoms. If she were cheekier, Her Majesty would have put those items on the piano. As it stands, I’ve never heard any of the senior royals even say the word condom, although I suspect Eleanor would pronounce it like my own grandmother did: as if it’s the nickname of the local cad who scandalizes all the gossips in the retirement village. (“Did you see Con Dom at the grocery store? He was buying six boxes of wine and a frozen burrito. What does it mean?”)

Suddenly, from across the room, a red beaded frame in the collection catches my eye. I could swear it wasn’t there yesterday, and when I move closer, the sight of the photo inside gives me the chills. The press would salivate over it, which is precisely why I thought it was locked away in Mom’s wall safe, behind a yard-sale portrait of a rich-looking lady whom she pretends is a distant moneyed aunt from the continent. In the picture, which Dad took on a family trip to Disney World, Lacey and I are eight. She is clutching Cinderella’s hand with the same urgent glee you see in people waiting to hear if they’re about to come on down on The Price Is Right, and wears a poufy pink gown and a tiara on her golden ringlets. I am a careful half step away, in shorts and Tevas, attempting a smile that fails to conceal my boredom. My dreams back then were to swim the individual medley at the Olympics, or play Major League Baseball; the Disney version of happily ever after didn’t impress me, and you can see that all over my face, as clear as the adoration in Lacey’s eyes. It is the perfect photo of mismatched twins, but beyond that, it’s deeply ironic given who Lacey and I have become, which is exactly why I asked Mom to hide it. I look like I hate Cinderella, yet now, to the world, I am Cinderella. The headline writes itself, and so does the karmic warning: Be careful what you pointedly don’t wish for, because one day you might find yourself getting armpit Botox to avoid headlines like THE DUCHESS OF SWEATSHIRE. Dragging this photo out reeks of Lacey, and ordinarily, I’d have assumed she did it for a laugh. But today it feels like a threat. When my phone vibrates again, I half expect it to be her.

It’s not.

YOU CAN’T PRETEND NOTHING HAPPENED.

That much is abundantly clear. I just wish I had more time to think. Tomorrow morning, I am supposed to walk Westminster Abbey’s three-hundred-foot aisle, wearing the biggest skirt of my life—the gown has its own room at The Goring—and pledge myself for eternity to Prince Nicholas of Wales, a king-in-waiting. I cannot tremble. I cannot twitch, even if Gaz weeps that high-pitched wail of his. I cannot disappoint, I cannot bend, I cannot break, because two billion people will be watching (one of whom might even be that tired, retired Cinderella, who hopefully won’t recognize the kid who once regarded her with so much skepticism). So, no, I can’t pretend nothing happened. But if I acknowledge it out loud…

My phone lights up and I jump so violently that I almost drop it.

“Morning, love,” my mother says, in the England-via-Iowa accent she’s adopted. The press has nicknamed her Fancy Nancy. “I’m actually looking for Lacey. Is she there?”

I snort.

“Bex, no swining,” Mom says, parroting a pun of Dad’s.

“The Daily Mail says she got a spray tan for three hours yesterday. Wherever she is, I’m sure she’s happy. And orange.”

“Cut it out, Rebecca.” That was a hundred percent American. My mother’s faux accent always disappears when she’s irritated. “You’re getting married tomorrow. Do your twin thing and apologize and fix it.”

Irritation strains my voice. “I can’t apologize if I wasn’t wrong.”

And I wasn’t, not about that. I’m squarely in the wrong now—Mom has no idea—but then again, so is Lacey, and I can’t always be the one to lay down my sword to keep the peace. Especially not when I’m under attack.

I hear a fumbling at the suite’s front door. “Mom, I have to go. The Bex Brigade is here.”

Within seconds the room is swarmed by stylists, seamstresses, security officers, and all manner of other Lyons operatives. I shove the blackmail-worthy photo deep behind a seat cushion. Out of sight, out of mind.

“Cheers, Bex, you look like microwaved shite,” chirps my personal secretary, Cilla.

“I’m just overtired.” It’s technically not a lie. “Actually, is it okay if I take a few more minutes?”

Cilla cocks an eyebrow, then nods briskly and hands me my usual stack of newspapers and tabloids. I excuse myself to my bedroom and fan them out on the paisley comforter. I’m everywhere. The Guardian’s front-page piece, GREAT BEXPECTATIONS, is about international wedding fever. WE’RE SO BEXCITED!, screeches The Sun, before handicapping what I’ll wear down the aisle. HALF HUMAN HALF CHEESE WHEEL BORN TO LEICESTER COUPLE: Mother Weeps, “I Always Knew We’d Brie Blessed,” claims the Daily Star, dwarfing a blurb about whether I’d forced Nick to get hair plugs. The goofy photo they picked to illustrate this makes me smile. I haven’t slept beside Nick all week, and I miss him—his bedhead, the snores that could dwarf a thunderstorm, the way he can’t fall asleep unless we are touching. I even miss that he always burns the first waffle he toasts. I fell in love with a person, not a prince; the rest is just circumstance.

The problem is, it can be hard to remember that. Which is how I got myself into trouble.

A text comes through: TIME IS RUNNING OUT.

With a thump Lacey bursts into my room, atypically ashen considering how much money she spends never to be that color. I am so startled to see her that I can only blink as she slams the door and leans breathlessly against it. She feels so far away from me even though she’s standing right here.

“I did something,” Lacey begins, not quite making eye contact.

So did I, but of course she already knows that. Once upon a time, I would ask for her help, us against the world. Now, it’s her against me, and the world probably will pick her side.

I might be Cinderella today, but I dread who they’ll think I am tomorrow. I guess it depends on what I do next.

Chapter One

If you believe my unauthorized biography, The Bexicon, Nick fell in love with me at a pub on my first night at Oxford, and angels burst into song while rose petals fell from the sky:

The King’s Arms was packed with reveling youngsters hungry for one last bit of mischief before the new term. But Rebecca Porter radiated a halo of confidence and serenity, modestly leaning against the back wall, holding a ladylike half-pint she would only sip twice. “Bex was never a drinker,” a friend says. “She knew how to have a laugh, but you’d never find her dancing on a table to impress people.” Indeed, the more he watched the seraphic American student—diffident and humble in sweetly vintage clothes surely destined for the Victoria and Albert Museum—the more Nicholas knew he had to claim her. He had found someone special. He had found his queen.

Complete fiction. In fact, the whole book is so inaccurately gushy that I often wonder if the author is on Queen Eleanor’s payroll. The week it was published, we were in Spain at what everyone refers to as “Prince Richard’s cabin”—Nick’s father’s coastal spread with fourteen bedrooms and its own vanity winery—and Nick laughed so raucously when I read this section aloud that his aunt Agatha, a full fifty yards away, jumped and dropped her gin and tonic.

“Are you sure it doesn’t say, ‘You’d never not find her dancing on a table’?” he’d asked. “Isn’t that more accurate?”

“I am not table dancing right now.”

“Pity,” he grinned, raising his scotch to me.

“There’s still time,” Nick’s younger brother, Freddie, had said from his deck chair. “In fact, Agatha over there could use some pointers. I don’t think she’s had any fun since she married Awful Julian.”

In reality, Agatha does occasionally have fun, though usually only when needling her boozy bounder of a husband about how his ancient father refuses to die (and thus hand down his viscountcy). Nick and I never went to The King’s Arms, because pubs with royal nomenclature make him self-conscious. And when fate pushed a prince into my path, my hair was dirty, I smelled like the canned air of the Virgin Atlantic plane that had deposited me at Heathrow, and my jeans and sailor-striped T-shirt could only be classified as vintage because of their extreme age. Aurelia Maupassant, author of The Bexicon, would be crushed.

* * *

When we were small, Lacey and I would sneak flashlights under the covers to read aloud from books about plucky British kids, their boarding-school hijinks, and their ill-fated wartime love affairs. Lacey was obsessed with the swoony kissing parts, but what stuck with me was a different kind of romanticism—the sense of epic sprawl compressed onto a small island that positively burst with art, antiquities, and history hiding in plain sight. I itched to inhale it, to live it, to sketch it all. So when I found out Cornell could do an exchange with the University of Oxford, I applied about five minutes later. Oxford didn’t sound as overwhelming as London, yet every photo I saw of its glorious collage of buildings—never quite new, so much as old, older, and oldest—promised it would be an artist’s dream. The tour guides tell you to try every door you find because it just might open, and it feels true; there are still quaintly cobbled streets with perfect, petite gardens behind wrought iron gates, and its picturesque nooks and crannies all but vibrate with centuries of secrets waiting to be unearthed. Its mystery, its age, its textures…Oxford is in all ways the opposite of Muscatine, my rural Iowa hometown (or even the bucolic North Atlantic beauty of Cornell), and for me it was perfect. I didn’t come to England to fall in love with anything but England. I didn’t come to get married. I came to draw. I came to be inspired. I came for adventure.

I suppose I got it.

Oxford’s student body trickles in as many as two weeks before the beginning of the new term—the crew team needs to adjust its sleep cycle just as much as a jet-lagged American does—so I arrived late on a mid-September afternoon with about ten days to unpack, recalibrate, and explore. The academic colleges there function like mini-universities under the Oxford umbrella—as if my old Cornell dorm also had its own professors and classrooms—and I had been accepted to live and study in one called Pembroke. It was smaller than some of the other thirty-seven dotted around town, and its lack of notoriety may directly correlate to being right across the street from the imposing, absurdly famous Christ Church college. We lived in its shadows—literally, come late afternoon—and during my year there, when the omnipresent red tour bus stopped to point out the historic building that was in the Harry Potter movies and observes its own time zone, the guide wouldn’t even so much as glance across the street. Now, Pembroke is the main stop on the Royal Romance tour, which leaves from the train station every forty-five minutes. According to Gaz, who took it six months ago on a lark, it’s almost as fictional as The Bexicon. He cried anyway.

A light drizzle was falling that first day as I hauled two giant suitcases, a laptop bag, and my purse up the cobblestone road toward Pembroke’s main entrance. My suitcase kept catching a wheel and flipping over, twisting my wrist and causing my shoulder bags to whack me in the leg; by the time I reached the door, I was panting and had slim rivulets of rain dribbling down my nose. I rang twice for the porter and cursed loudly when no one answered. It had been a plane, train, and automobile odyssey to get me from Des Moines to that front stoop. I was cold, wet, and exhausted, and, from what I could tell, my deodorant had not stood up to the journey.

I buzzed again. The door opened and a tall, sandy-haired guy poked out his head.

“Need a hand?”

“Oh, please. Yes. Thank you.”

He held up a stern palm. “Wait, how do I know you’re supposed to be here? I heard you swearing. Foul language doesn’t befit an Oxford student.”

I stammered an apology until I noticed he was grinning.

“I’m joking,” he said. “You’re Rebecca. I was told you’d be coming.” He widened the door and came through to get my bags. “The porter is very protective of his tea break, so I said I’d sit in and look out for you.”

“And you let me hang out here in the rain just for fun? Is that behavior befitting an Oxford student?” I said, stepping inside, cozy and warm after the rain.

“I may have been engaged in an in-depth study of REM sleep.” He shrugged winningly. “I’ve had two pints already and they make me so tired. Besides, I couldn’t have guessed you’d show up without an umbrella. That’s like going to the Bahamas without a bathing suit.” He hoisted up my bags. “Follow me.”

We trudged up the winding dark wood stairs, past stately oil paintings that looked so rustic they had to be originals, and blank-eyed portraits of alumni and monarchs.

“Which one is he?” I pointed to a man with a square jaw and a beard as thin as he was fat.

“That’s King Albert. Victoria the First’s grandson. Early nineteen-hundreds.”

“I feel like he’s staring right through me,” I said, shivering involuntarily as we wound our way up to the third floor. “He has kind of a homicidal face. Or is that just syphilis making him insane? British monarchs do love their syphilis.”

“A prerequisite of the job,” he agreed.

I snorted, at which he shot me a startled but amused glance before I followed him into a slender hallway, domed with carved beams and lit beguilingly with candle-shaped sconces. We passed six doors—three on each side—and stopped outside the last one on the left.

“Here you go,” he said, digging in the pocket of his jeans and then handing me a key. “Stop by the porter later and he’ll give you a full set. And come join us in the JCR, if you’re so inclined.” He gave me a crisp nod. “Welcome to Oxford.”

He was gone before my numbed mind got off a thank-you, much less decoded that acronym. I fought a head-splitting yawn and fumbled with the key—right as the door opposite mine flew open and an auburn-haired girl shot out of it and grabbed my hand.

“I see you’ve met him, then,” she said, in an accent I later learned was Yorkshire. “What d’you think? Rather nice for a guy whose face will be all over our money in fifty years.” She smacked her forehead. “Oi, I’m a dolt. Sorry. I’m Cilla.”

“Rebecca,” I said, blinking hard. “And are you telling me that was…?”

“Nick, yes,” she said. “Or rather, ‘Prince Nicholas of Wales.’” She made the air quotes with four fingers whose nail polish was in various stages of peeling. “He’s not insufferable about the title, thank God.” She peered at my glazed eyes. “Didn’t you recognize him?”

That I hadn’t was laughable (he still teases me that it’s treasonous not to tip your royal baggage handler). Lacey subscribed to every celebrity weekly in existence—she delighted in reading bits of them to me once she’d finished her homework, usually while I was still trying to do mine—and Nick had appeared in them all. But in person he lacked the macho sheen the media always tried to give him, and I don’t care who you are or how many times your twin has told you to practice constant vigilance: You still don’t expect the so-called Heartthrob Heir to be your glorified bellhop.

“So the future sovereign just heard me accuse his relative of having syphilis?” I asked faintly.

“Oh, that’s a good one,” Cilla said. “But don’t worry. Gaz once threw up all over him and Nick didn’t even bat an eyelash, and that’s saying something because Gaz eats a lot and there were loads of chunks.” She grabbed a bag and barged past me into my room.

I finagled my other suitcase through the doorway and took in my new home. There was an irony in coming all the way to Oxford to find that my room resembled the ones in every dorm in America: a twin bed with a metal bedframe, a radiator under the window, and a desk with a hutch that looked like it came from an office supply warehouse.

Cilla nodded at a heap in the corner. “I filched some of Ceres’s things that she didn’t take when she left,” she said. “A rug, some throw pillows. Whatever might make it less awful in here. We can decorate later, though. First let’s get you to the bar for a welcome drink.”

“Shouldn’t I change?” I asked, wondering if I smelled bad to people whose noses weren’t as close to me as my own was.

Cilla waved at her torn jeans, creased boots, and woolly sweater. “Yes, we stand on formality here at Pembroke,” she intoned. “Actually, Ceres would put on high heels and lipstick to go down and get the mail. If you’re going to take that long, I’ll just meet you downstairs.”

I shook my head. “Can’t walk in heels and never met a lipstick I didn’t get on my teeth.”

Cilla beamed broadly. “We’ll get on splendidly, then, Rebecca.”

“Bex. Please.”

“Okay, Bex. Get on with it already. It’s been ten whole minutes since my last pint.”

* * *

It turned out the bar was the JCR—a dim undergraduate common area that looked cramped thanks to the jumble stuffed into it: mismatched chairs and chipped tables; a haphazardly hung flat-screen showing soccer highlights; and a substantial but inexpensive beer and booze collection, stocked by that year’s Bar Tsar (his elaborately framed photo hung on the wall). Even with the haze of cigarette smoke hanging in the air, it was easy to spot Nick because at least half the room was ogling him, and I had only to follow the stares. He was perched on a stool in a snug corner, relaxed and quiet, with two guys and a punky girl who did not wear her pink hair with much authority. Cilla steered me through the crowd right in their direction. She may have been small, but she was solid, efficiently built, and clearly not to be trifled with, because people parted for her as if by magic.

“These are more of the people in our corridor,” she said when she reached Nick’s corner. “Everyone, this is Bex, just in from America.”

One of them bounced to his feet so fast he almost knocked over the table. He had a kind face, bulbous nose, freckles, and a thick tuffet of orange-red hair—rather like Ron Weasley, but with scruff, and a round, compact belly that was either the product of a lot of lager, or his (ineffective) attempts to draw in enough air to appear taller than five foot six. Possibly both.

“Brilliant,” he said. “I’m Gaz. I expect Cilla’s told you all about me.”

“Just the vomity bits,” Cilla said.

Gaz grinned even wider. “That’s about all of it.”

A bespectacled dark-haired guy rose to his feet. “Please, sit. I’ll get drinks,” he said, gesturing to the threadbare, oversize chair he’d just vacated, and pulling out folded bills that were tucked into his back pocket with the same precision as the plaid collared shirt tucked into his jeans.

“That wonderful person with the fat wad of cash is Clive,” Gaz said. “And this young lady with the shirt that looks like she made it out of tea towels is Joss.”

“And I did make it out of tea towels,” Joss said, appraising me as Cilla and I squeezed into Clive’s empty seat. “Ceres was my fit model, but you’ll do nicely. Built just like her. Tall, no boobs.”

“Finally, being flat chested is an advantage,” I said. “My twin sister will be astonished.”

“Oooh, twins, eh?” Gaz said, wiggling his eyebrows.

“Get off it,” Cilla scoffed. “Gaz thinks he’s dead suave, but his father is a disgraced finance minister, so it’s more like dead broke. He still owes me thirty quid from last term.”

“I make up for it with piles of charm,” Gaz said. “And this bloke here,” he said, gesturing at Nick, “is…Steve.”

He adopted a deep, dramatic intonation, lingering on the word like it was a rich dessert to be savored. Nick buried his face in his beer, but the telltale bubbles gave away his laughter.

“Steve,” I echoed, trying on Gaz’s tone for size. “Sure. I can roll with that, Steve.”

Gaz slapped the table, which reverberated under his meaty hand. “You told her?”

“She’d have figured it out anyway,” Cilla said. “So take it down about three point sizes, please, Garamond.”

Clive was back and sliding the drinks onto the scarred coffee table. “‘Gaz’ is short for ‘Garamond,’ of the Fonty Garamonds,” he explained.

“As in, the actual font,” Joss piped up. “His grandfather invented it.”

“He’s mad as pants. Won’t even read anything in sans serif,” Gaz said. “Couldn’t he have invented something cooler to be named after? Like Garamond the Time-Traveling Motorbike, or Garamond the Lady-Killing Love Tonic?”

“I thought you were Garamond the Lady-Killing Love Tonic,” Cilla cracked.

“Well, as long as we’re talking stupid names,” he said irritably, “somebody tell me why we bother with Steve if none of you uses it.”

Nick rubbed the top of his head absently. “It’s not really supposed to fool anyone,” he said. “It’s more for if I’m caught in trouble or doing anything embarrassing.”

I met his eyes. “Embarrassing, like joking to a prince that all his relatives have an STD?”

“Exactly,” he said. “Although no one in polite society would actually do that.”

We smiled at each other.

Clive turned to me and pretended to study me deeply, as if my eyelashes were tea leaves he could read. “And you are…Rebecca Porter, almost twenty, from Iowa, father invented a sofa that employs a mini-fridge as a base—”

“Can you get us one?” Gaz interjected.

“…and you once got arrested for public indecency and trespassing because you accidentally tore off your trousers while climbing a barbed-wire fence,” Clive finished.

“I maintain it tried to climb me,” I quipped. “What else does my dossier say? Or do you just have ESP?”

“Of course there’s a dossier,” Gaz said, clapping a hand on Nick’s shoulder. “The Firm has to know who’s living twenty feet from the future of the bloodline.”

Nick’s discomfort was clear (one of his tells is that the tops of his ears start to vibrate—it’s the strangest thing). He drained the last of his pint. “While you lot are busy frightening Bex, I need to go say hello to some people.”

“Yes, right. Back to the grind.” Clive grinned, nodding toward a giggling, coquettish cluster of blondes across the way.

“There are probably worse fates,” Nick said. “I hear syphilis is a beast.”

He slipped off into the room, but didn’t make it far before he was waylaid by a cranky-looking patrician brunette in a high-collared blouse, who pulled him over to whisper in his ear.

Clive whacked Gaz on the arm. “You know he’s sensitive about the king stuff.”

“But it’s exciting!” Gaz argued. “Big intrigue. I’m very respectful.”

Cilla looked doubtful as Joss checked her cell phone. “I’m meeting Tank at the new punk bar over by the Ashmolean,” she said. “Anybody want to come?”

I glanced around for guidance. Cilla shook her head.

“Suit yourselves,” Joss said, leaving behind a quarter of a pint.

“Don’t mind if I do,” Gaz said brightly, reaching over and swigging it.

“Really, Gaz,” Cilla nagged. “You’ll be sweating lager next. My great-grandmother’s great-uncle Algernon had that happen when he was courting the Spanish infanta and—”

“Ah, yes, here we go again,” grunted Gaz.

“Cilla has more stories than Nick has stalkers,” Clive told me. “I’ve no clue if any of it’s true, but it’s bloody entertaining.”

“…and then of course she broke it off with him by trying to thrust a letter opener into his ear at her brother’s coronation,” Cilla was saying.

To better bark at him, Cilla clambered into the empty chair next to Gaz. Clive responded by settling into her old spot, smashed up next to me, our thighs touching. It wasn’t unpleasant. He was the Hollywood archetype of a sensitive yet smoldering Brit—wavy jet-black hair, strong jaw, and a voice that was smooth and husky all at once.

“So, Bex, what are you reading?”

“Reading?”

“Studying,” he clarified.

“It’s not in my file?”

Clive smiled. “We only got the juicy bits,” he said, sipping his drink and then licking the froth off his lip in a way that suggested he enjoyed my watching him do it.

“Well, theoretically I’m reading British history, toward my degree at home, but what I really want to do over here is draw,” I said. “I mostly work in pencils, and so much of the architecture here lends itself to dramatic gray and black areas. The arches, the carvings, the gargoyles…”

“Did I hear you say gargoyles?” Gaz interrupted. “That reminds me.” He pointed at the stern brunette. “That is our other floor-mate, Lady Beatrix Larchmont-Kent-Smythe. Otherwise known as Lady Bollocks, because of her initials, and also, she can be a bloody load of it.”

Lacey later described Bea as looking and acting exactly the way you would expect a Lady Beatrix Larchmont-Kent-Smythe to look and act. Her posture is as impeccable as her tailoring, she never loses her keys nor her cool nor so much as a chip from her manicure, and I believe she intentionally waxes her eyebrows so that she always appears to be raising them at you with deepest skepticism. Clive explained that Lady Bollocks was a lifelong friend of Nick’s family, and in fact, as we alternated pints and gin-filled highballs, he turned out to be full of tidbits: that Cilla’s ancestors lost their money in a lusty Downton Abbey–style scandal; that the girl tending bar once had a pop hit called “Fish and Chips” about a memorable weekend with a famous boy band; that two hundred people had money on whether Cilla and Gaz would sleep together or murder each other (he had a hundred pounds on them doing both); and that Joss’s continued enrollment was a mystery to everyone, because she rarely did anything except follow around her boyfriends and make clothes in her room, to the consternation of her pushy father—the Queen’s gynecologist.

“She’s a good enough sort, but we don’t see her much,” Clive said. “Her father requested she be on Nick’s floor, to light a fire under her or some such, and you don’t run afoul of a man who has such, er, sensitive personal information.”

“Keep your friends close, keep the secrets of the Royal Birth Canal closer,” I said.

“Something like that.” His hand brushed my leg again.

“And you’re the person everyone wants to sit next to at a wedding,” I said. “You’d have dirt on everyone in the room and at least two of their relatives.”

“Only two?” Clive feigned shock. “I do want to be a reporter, actually. I like learning about people. My brothers think it’s just an excuse for the fact that I’m afraid of having my ears torn off.” At my quizzical expression, he added, “They play rugby. Professionally. The biggest, thickest clods you’ve ever seen. Cauliflower ears and broken noses and all.”

“So how did you e

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved