- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Two thieves want answers. Riyria is born.

For more than a year, Royce Melborn has tried to forget Gwen DeLancy, the woman who saved him and his partner Hadrian Blackwater. Unable to stay away any longer, they return to Medford to a very different reception - she refuses to see them.

Once more she is shielding them, this time from the powerful noble who abused her. But she doesn’t know the rules Royce would break to see her safe.

A W. F. Howes audio production.

Release date: September 17, 2013

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 384

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

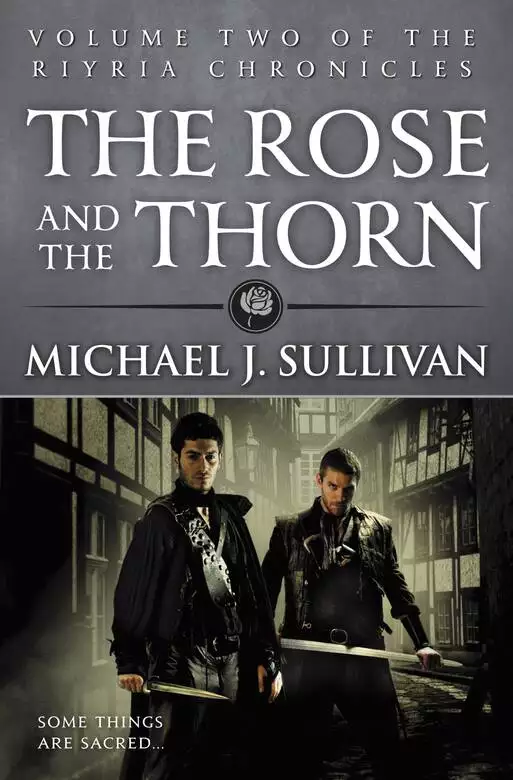

The Rose and the Thorn

Michael J. Sullivan

“Reuben! Hey, Reuben!”

Reuben? Not Muckraker? Not Troll-Boy?

The squires all had nicknames for him. None were flattering, but then he had names for them too—at least in his head. “The Song of Man,” one of Reuben’s favorite poems, mentioned age, disease, and hunger as the Three Cruelties of Humanity. Fat Horace was clearly hunger. Pasty-faced, pockmarked Willard was disease, and age was given to Dills, who at seventeen was the oldest.

Spotting Reuben, the trio had whirled his way like a small flock of predatory geese. Dills had a dented knight’s helmet in his hands, the visor slapping up and down as it swung with his arm. Willard carried combat padding. Horace was eating an apple—big surprise.

He could still make it to the stable ahead of them. Only Dills had any chance of winning in a footrace. Reuben shifted his weight but hesitated.

“This is my old trainer,” Dills said pleasantly, as if the last three years had never happened, as if he were a fox who’d forgotten what to do with a rabbit. “My father sent a whole new set for my trials. We’ve been having fun with this.”

They closed in—too late to run now. They circled around, but still the smiles remained.

Dills held out the helmet, which caught and reflected the autumn sun, leather straps dangling. “Ever worn one? Try it.”

Reuben stared at the helm, baffled. This is so odd. Why are they being nice?

“I don’t think he knows what to do with it,” Horace said.

“Go ahead.” Dills pushed the helmet at him. “You join the castle guards soon, right?”

They’re talking to me? Since when?

Reuben didn’t answer right away. “Ah… yeah.”

Dills’s smile widened. “Thought so. You don’t get much combat practice, do you?”

“Who would spar with the stableboy?” Horace slurred while chewing.

“Exactly,” Dills said, and glanced up at the clear sky. “Beautiful fall day. Stupid to be inside. Thought you’d like to learn a few maneuvers.”

Each of them wore wooden practice swords and Horace had an extra.

Is this real? Reuben studied their faces for signs of deceit. Dills appeared hurt by his lack of faith, and Willard rolled his eyes. “We thought you’d like to try on a knight’s helmet, seeing as how you never get to wear one. Thought you’d appreciate it.”

Beyond them, Reuben saw Squire Prefect Ellison coming from the castle and taking a seat on the edge of the well to watch.

“It’s fun. We’ve all taken turns.” Dills shoved the helm against Reuben’s chest again. “With the pads and helm you can’t get hurt.”

Willard scowled. “Look, we’re trying to be nice here—don’t be a git.”

As bizarre as it all was, Reuben didn’t see any malice in their eyes. They all smiled like he’d seen them look at one another—sloppy, unguarded grins. The whole thing made a kind of sense in Reuben’s head. After three years the novelty of bullying him had finally worn off. Being the only one their age who wasn’t noble had made him a natural target, but times had changed and everyone grew up. This was a peace offering, and given that Reuben hadn’t made a single friend since his arrival, he couldn’t afford to be picky.

He lifted the helm, which was stuffed with rags, and slipped it on. Despite the wads of cloth, the helmet was too big, hung loose. He suspected something wasn’t right but didn’t know for sure. He had never worn armor of any kind. Since Reuben was destined to be a castle soldier, his father had been expected to train him but never had time. That deficiency was part of the allure of the squires’ offer; the enticement outweighed his suspicions. This was his chance to learn about fighting and swordplay. His birthday was only a week away, and once he turned sixteen he would enter the ranks of the castle guard. With little combat training he’d be relegated to the worst posts. If the squires were serious, he might learn something—anything.

The trio trussed him up in the heavy layers of padding that restricted his movement; then Horace handed him the extra wooden sword.

That’s when the beating began.

Without warning, all three squires’ swords struck Reuben in the head. The metal and wadding of the helmet absorbed most, but not all, of the blows. The inside of the helmet had rough, exposed metal edges that jabbed, piercing his forehead, cheek, and ear. He raised his sword in a feeble attempt to defend but could see little through the narrow visor. His ears packed with linen, he could just barely make out muffled laughter. One blow knocked the sword from his hands and another struck his back, collapsing him to his knees. After that, the strikes came in earnest. They rained on his metal-caged head as he cowered in a ball.

Finally the blows slowed, then stopped. Reuben heard heavy breathing, panting, and more laughter.

“You were right, Dills,” Willard said. “The Muckraker is a much better training dummy.”

“For a while—but the dummy doesn’t curl up in a ball like a girl.” The old disdain was back in Dills’s voice.

“But there is the added bonus of him squealing when hit.”

“Anyone else thirsty?” Horace asked, still panting.

Hearing them move away, Reuben allowed himself to breathe and his muscles to relax. His jaw was stiff from clenching his teeth, and everything else ached from the pounding. He lay for a moment longer, waiting, listening. With the helmet on, the world was shut out, muted, but he feared taking it off. After several minutes, even the muffled laughter and insults faded. Peering up through the slit, all he could see was the canopy of orange and yellow leaves waving in the afternoon breeze. Reuben tilted his head and spotted the Three Cruelties in the center of the courtyard filling cups from the well as they took seats on the apple cart. One was rubbing his sword arm, swinging it in wide circles.

It must be exhausting beating me senseless.

Reuben pulled the helmet off and felt the cool air kiss the sweat on his brow. He realized now that it wasn’t Dills’s helm at all. They must have found it discarded somewhere. He should have known Dills would never let him wear anything of his. Reuben wiped his face and was not surprised when his hand came away with blood.

Hearing someone’s approach, he raised his arms to protect his head.

“That was pathetic.” Ellison stood over Reuben, eating an apple that he had stolen from the merchant’s cart. No one would say a word against him—certainly not the merchant. Ellison was the prefect of squires, the senior boy with the most influential father. He should have been the one to prevent such a beating.

Reuben didn’t reply.

“Wadding wasn’t tight enough,” Ellison went on. “Of course, the idea is not to get hit in the first place.” He took another bite of apple, chewing with his mouth open. Bits of dribble fell to his chest, staining his squire’s tunic. He and the Cruelties all wore the same uniform, blue with the burgundy and gold falcon of House Essendon. With the stain of apple juice, it looked like the falcon was crying.

“It’s hard to see in that helm.” Reuben noticed the wadded cloth that had fallen on the grass was bright with his blood.

“You think knights can see better?” Ellison asked around a mouthful of apple. “They ride horses while fighting. You just had a helm and a touch of padding. Knights wear fifty pounds of steel, so don’t give me your excuses. That’s the problem with your kind—you always have excuses. Bad enough we have to suffer the indignity of working alongside you as pages, but we also have to listen to you complain about everything too.” Ellison raised the pitch of his voice to mimic a girl. “I need shoes to haul water in the winter. I can’t split all the wood by myself.” Returning to his normal tone, he continued, “Why they still insist on forcing young men of breeding to endure the humiliation of cleaning stables before becoming proper squires is beyond me, but having the added insult of being forced to labor alongside someone like you, a peasant and a bastard, was just—”

“I’m no bastard,” Reuben said. “I have a father. I have a last name.”

Ellison laughed and some of the apple flew out. “You have two —his and hers. Reuben Hilfred, the son of Rose Reuben and Richard Hilfred. Your parents never married. That makes you a bastard. And who knows how many soldiers your mother entertained before she died. Chambermaids do a lot of that, you know. Whores every one. Your father was just dumb enough to believe her when she said you were his. That right there shows you the man’s stupidity. So assuming she wasn’t lying, you’re the son of an idiot and a—”

Reuben slammed into Ellison with every ounce of his body, driving the older boy to his back. He sat up swinging, hitting Ellison in the chest and face. When Ellison got an arm free, Reuben felt pain burst across his cheek. Now he was on his back and the world spun. Ellison kicked him in the side hard enough to break a rib, but Reuben barely felt it. He still wore his padding.

Ellison’s face was red, flushed with anger. Reuben had never fought any of them before, certainly not Ellison. His father was a baron of East March; even the others didn’t touch him.

Ellison drew his sword. The metal left the sheath with a heavy ring. Reuben just barely grabbed the practice wood, which had been left lying in the grass. He brought it up in time to prevent losing his head, but Ellison’s steel cut it in half.

Reuben ran.

That was the one advantage he had over them. He did more work and ran everywhere while they did little. Even weighed down by the padding, he was faster and had the stamina of a pack of hounds. He could run for days if needed. Even so, he wasn’t fast enough, and Ellison got one last blow across Reuben’s back. The slice only served to drive him forward, but when he was safely away, he discovered a deep cut through all four layers of padding, his tunic, and a bit of skin.

Ellison had tried to kill him.

Reuben hid in the stables the rest of the day. Ellison and the others never went there. Horse Master Hubert had a tendency to put any castle boy to work, failing to notice the difference between the son of an earl, a baron, or a sergeant at arms. One day they might be lords, but right now they were pages and squires, and as far as Hubert was concerned, they were all just backs and hands to lift shovels. As expected, Reuben was put to mucking out the stalls, which was better than confronting Ellison’s blade. His back hurt, as did his face and head, but the bleeding had stopped. Given that he could have died, he wasn’t about to complain.

Ellison was just angry. Once he calmed down, the prefect would find another way to demonstrate his displeasure. He and the squires would trap and beat him—with the woods most likely, but without the padding or helmet.

Reuben paused after dumping a shovelful of manure into the wagon and sniffed the air. Wood smoke. Kitchens burned wood all year, but it smelled different in the fall—sweeter. Planting the shovel’s head, he stretched, looking up at the castle. Decorations for the autumn gala were almost complete. Celebration flags and streamers flew from poles, and colored lanterns hung from trees. Though the gala was held every year, this time would be a double celebration in honor of the new chancellor. That meant it had to be bigger and better, so they adorned the castle inside and out with pumpkins, gourds, and tied stalks of corn. When the question of too few chairs arose, bundles of straw were hauled in to line every room. For the last week, farmers had been dropping off wagons full. The place did look festive, and even if Reuben wasn’t invited, he knew it would be a wonderful party.

His sight drifted to the high tower, which had lately become his obsession. The royal family resided in the upper floors of the castle, where few were allowed without invitation. The tallest point of the castle held its title by only a few feet, but it soared in Reuben’s imagination. He squinted, thinking he might see movement, someone passing by the window. He didn’t, but then nothing ever happened in the daylight.

With a sigh, he returned to the dimness of the stable. Reuben actually enjoyed shoveling for the horses. In the cooler weather there were few flies and most of the manure was dry, mixed with straw to the consistency of stale bread or cake, and it barely smelled. The simple, mindless work granted him a sense of accomplishment. He also enjoyed being with the horses. They didn’t care who he was, the color of his blood, or if his mother had married his father. They always greeted him with a nicker and rubbed their noses against his chest when he came near. He couldn’t think of anyone he’d rather spend the autumn afternoon with, except one. Then, as if thoughts could grant wishes, he caught the flash of a burgundy gown.

Seeing the princess through the stable’s door, Reuben found it hard to breathe. He froze up whenever he saw her, and when he could move, he was clumsy—his fingers turned stupid, unable to perform the simplest of tasks. Luckily he’d never been called on to speak in her presence. He could only imagine how his tongue would make his fingers appear deft. He’d watched her for years, catching a glimpse as she climbed into a carriage or greeted visitors. Reuben had liked her from first sight. There was something about the way she smiled, the laughter in her voice, and the often serious look on her face, as if she were older than her years. He imagined she wasn’t human but some fairy—a spirit of natural grace and beauty. Spotting her was rare and that made it special, a moment of excitement, like seeing a fawn on a still morning. When she appeared, he couldn’t take his eyes off her. Nearly thirteen, she was as tall as her mother. But there was something in the way she walked and how her hips shifted when she stood too long in one place that showed she was more lady than girl now. Still thin, still small, but different. Reuben fantasized of being at the well one day when she appeared in the courtyard alone and thirsty. He pictured himself drawing water to fill her cup. She would smile and perhaps thank him. As she brought the empty cup back, their fingers would meet briefly and for that one moment he would feel the warmth of her skin, and for the first time in his life know joy.

“Reuben!” Ian, the groom, struck him on the shoulder with a riding crop. It stung enough to leave a mark. “Quit your daydreaming—get to work.”

Reuben resumed shoveling the manure, saying nothing. He had learned his lesson for the day and kept his head down while scooping the strata of dirt cakes. She could not see him in the stalls, but with each toss of manure he caught a glimpse of her through the door. The princess wore a burgundy dress, the new one of Calian silk that she had received for her birthday along with the horse. To Reuben, Calis was just a mythical place, somewhere far away to the south filled with jungles, goblins, and pirates. It had to be a magical land because the material of the dress shimmered as she walked, the color complementing her hair. Being the newest, it fit well. More than that, the other dresses were for a girl—this was a woman’s gown.

“You’ll be wanting Tamarisk, Your Highness?” Ian asked from somewhere in the stable’s main entry.

“Of course. It’s a beautiful day for a ride, isn’t it? Tamarisk likes the cooler weather. He can run.”

“Your mother has asked you not to run Tamarisk.”

“Trotting is uncomfortable.”

Ian gave her a dubious look. “Tamarisk is a Maranon palfrey, Your Highness. He doesn’t trot—he ambles.”

“I like the wind in my hair.” There was a certain flair in her voice, a willfulness that made Reuben smile.

“Your mother would prefer—”

“Are you the royal groom or a nursemaid? Because I should tell Nora that her services are no longer needed.”

“Forgive me, Your Highness, but your mother would—”

She pushed past the groom and entered the barn. “You there—boy!” the princess called.

Reuben paused in his scraping. She was looking right at him.

“Can you saddle a horse?”

He managed a nod.

“Saddle Tamarisk for me. Use the sidesaddle with the suede seat. You know the one?”

Reuben nodded again and jumped to the task. His hands shook as he lifted the saddle from the rack.

Tamarisk was a beautiful chestnut, imported from the kingdom of Maranon. These horses were famed for their breeding and exquisite training, which made for exceptionally smooth rides. Reuben imagined this was how the king explained the gift to his wife. Maranon mounts were also known for their speed, which was likely how the king explained the gift to his daughter.

“Where will you be going?” Ian asked.

“I thought I would ride to the Gateway Bridge.”

“You can’t ride so far alone.”

“My father got me that horse to ride, and not just in the courtyard.”

“Then I will escort you,” the groom insisted.

“No! Your place is here. Besides, who will raise the alarm if I don’t return?”

“If you won’t have me, then Reuben will ride with you.”

“Who?”

Reuben froze.

“Reuben. The boy saddling your horse.”

“I don’t want anyone with me.”

“It’s me or him or no horse is saddled, and I’ll go to your mother right now.”

“Fine. I’ll take… what did you say his name was?”

“Reuben.”

“Really? Does he have a last name?”

“Hilfred.”

She sighed. “I’ll take Hilfred.”

Reuben had never sat a horse before, but he wasn’t about to tell either of them that. He was not afraid, except of making a fool of himself in front of her. He knew all the horses well and chose Melancholy, an older black mare with a white diamond on her face. Her name matched her temperament—an attitude that reflected her age. This was the horse they saddled for the children who wanted to ride a “real” horse or for grandmothers and matronly aunts. Still, his heart was pounding as Melancholy followed behind Tamarisk, something she would do even if Reuben wasn’t on her back.

They passed out of the castle gates into the city of Medford, the capital of the kingdom of Melengar. Reuben hadn’t had much education, but he was a great listener and knew Melengar was one of the smallest of the eight kingdoms of Avryn—the greatest of four nations of mankind. All four countries—Trent, Avryn, Delgos, and Calis—had at one time been part of a single empire, but that was long ago and of no importance to anyone but scribes and historians. What was important was that Medford was well respected, well-to-do, and at peace, and had been for a generation or more.

The king’s castle formed the central hub of the city, and around it cart vendors lay siege, circling the moat and selling all manner of autumn fruits and vegetables, breads, smoked meats, leather goods, and cider—both hot and cold, hard and soft. Three fiddlers played a lively tune next to an upturned hat placed on a nearby stump. Lesser nobles in cloaks or capes wandered the brick streets, fingering crafted baubles. Those of greater means rolled along in carriages.

The two rode straight down the wide brick avenue, past the statue of Tolin Essendon. Sculpted larger than life, the first king of Melengar was made to look like a god on his warhorse, though rumor had it he was not a big man. The artist might have aimed at capturing the full reality of Tolin rather than just his appearance, for surely the man who defeated Lothomad, Lord of Trent, and carved Melengar out of the ruins of a civil war had to have been nearly as great as Novron himself.

No one stopped or questioned Reuben and Arista as they rode by, but many bowed or curtsied. Several loud conversations actually halted when they approached, everyone staring. Reuben felt uncomfortable, but the princess appeared oblivious, and he admired her for it.

Once they were out of the city and on the open road, Arista increased their pace to a trot. At least his horse trotted, which was an unpleasant bouncing gait that caused the sword Ian had given him to clap against his thigh. Just as Ian had mentioned, the princess’s horse did not trot. The animal pranced as if Tamarisk wished to avoid soiling his hooves.

They continued along the road, and as Reuben’s comfort with the horse grew, so did a smile on his lips. He was alone with her, far away from Ellison and the Three Cruelties, riding a horse and wearing a sword. This was what a man’s life should be, what his life might have been if he’d been born noble.

Reuben’s fate was to join his father, Richard, in the service of the king as a man-at-arms. He would start on the wall or at the gate, and if lucky would work his way up to a more prestigious position like his father had. Richard Hilfred was a sergeant in the royal guard and one of those responsible for the personal protection of the king and his family. Such a title had benefits, such as securing a position for an untrained son. Reuben knew he should be thankful for the opportunity. Soldiers in a peaceful kingdom led comfortable lives, but so far life in Essendon Castle had been anything but comfortable.

In a week, on his birthday, he would don the burgundy and gold. Reuben would still be the youngest and weakest, but he would no longer be a misfit. He would have a place. That place would just never be on the back of a horse riding free on the open road with a real sword strapped to his belt. Reuben imagined the life of an errant knight, roaming the roads as he wished, seeking adventures, and gaining fame. That was the future of squires—their reward for stealing apples and beating him.

This ride might be the highpoint of his life. The weather was perfect, a late afternoon in fall. The sky a color of blue usually only seen in the crisp of winter, and the trees—many of which still had their leaves—were brilliant, as if the forests were ablaze but frozen in time. Scarecrows with pumpkin heads stood guard over the brown stalks of corn and late season gardens.

He breathed in the air; it smelled sweeter somehow.

Once they were down the road, the princess looked behind her. “Hilfred? Do you suppose they can see us from here?”

“Who, Your Highness?” he asked, amazed and grateful his voice didn’t crack.

“Oh, I don’t know. Anyone who might be watching… the guards on the walls or someone who may have put her needlework down in order to climb the east tower to look out the window?”

Reuben looked back. The city was obscured by the hill and the trees. “No, Your Highness.”

The princess smiled. “Wonderful.” She crouched low over Tamarisk’s back and made a clicking noise. The horse broke into a run, racing down the road.

Reuben had no choice but to follow, holding on to the saddle with both hands as Melancholy made a valiant effort, but the nineteen-year-old pasture mare was no match for the seven-year-old Maranon palfrey. The princess and her horse were soon out of sight and Melancholy settled to a trot, then slowed to a walk. Her sides were heaving, and nothing Reuben tried urged her to move any faster. He finally gave up and sighed in frustration.

He looked down the road, helpless. He considered abandoning Melancholy and running, for at that moment he could travel faster than the horse he was on. He didn’t know what to do. What if she had fallen? If only Melancholy could gallop as fast as his heart.

Plodding to the top of the next rise, he saw the princess. Arista was on her horse, standing at the Gateway Bridge, which marked the divide between the kingdom of Melengar and their neighboring kingdom of Warric. She spotted him but made no move to flee.

At the sight of her his panic vanished. She was safe. Looking at her mounted near the riverbank, Reuben decided the ride there was not the best time of his life—this was.

She was beautiful, and never more so than at that moment. Sitting tall in the saddle, the wind splaying the luxurious gown across the back and side of her horse. Her long shadow reached toward him as the setting sun bathed both, playing with Tamarisk’s mane and the silk of the dress the same way it played with the surface of the river. This moment was a gift, a wonder beyond words, beyond thought. Being alone with Arista Essendon in the setting sun—her in that womanly dress and he on horseback armed with a sword like a man, like a knight—was a perfect dream.

The thunder of hooves shattered the moment.

A group of horsemen burst out of the trees to Reuben’s left. Three riders raced down on him. He thought they would collide with his horse, but at the last moment they veered and raced by, cloaks flying behind them. Melancholy was startled by the near miss and bolted off the road. Even if Reuben had been an expert rider, he would’ve had trouble staying in the saddle. Caught off guard, and unfamiliar with the motions of horses, he fell, landing on the flat of his back.

He crawled to his feet as the riders made straight for the princess and circled her, laughing and hooting. Reuben was not yet a castle guard, but Ian had given him the sword for a reason. That there were three didn’t matter. That his ability with a sword could best be described, even in his own mind, as embarrassing, did not give him the slightest pause.

He drew the blade, sprinted down the hill, and when he reached them shouted, “Leave her alone!”

The laughter died.

Two of the three dismounted and drew swords together. The polished steel flashed in the low sun. As soon as they hit the ground, Reuben realized they were no more than boys, three or perhaps four years younger than himself. Their features were so similar they must have been brothers. Their swords were unlike the thick falchions of the castle guard or the short swords of the squires. They held thin, delicate weapons with adorned handguards.

“He’s mine,” the largest said, and Reuben could hardly believe his luck that the other two stayed back.

To defend the princess from ruffians, even if only children—to have her watch me fight for her honor, to be the one to save her. Please, Lord Maribor, I can’t fail… not at this!

The boy approached all too casually, puzzling Reuben. Shorter by a good five inches, thin as a cornstalk, and with the wind at his back, he struggled to keep his wild black hair from his eyes as he strode toward him, a huge grin on his face.

When he came within a sword’s length, he stopped and, to Reuben’s amazement, bowed. Then he rose, sweeping his sword back and forth, such that it sang in the air. Finally, he took a stance with bent knees, his free arm behind his back.

Then the boy lunged.

His speed was alarming. The tip of the little sword slashed across Reuben’s chest, failing to cut skin but leaving a gash in his smock. Reuben staggered backward. The boy advanced, shuffling his feet in a strange manner that Reuben had never seen before. The movements were fluid and graceful, as if he were dancing.

Reuben swung his sword.

The boy did not move. He did not raise his blade to parry. He only laughed as the attack missed by an inch. “I think I could just stand here trussed to a pole and you still couldn’t hit me. The lady should have found a more able protector.”

“That’s not a lady. That’s the Princess of Melengar!” Reuben shouted. “I won’t let you harm her.”

“Is she really?” He glanced over his shoulder. “Did you hear that? We’ve captured a princess.”

I’m an idiot. Reuben felt like stabbing himself.

“Well, we aren’t going to harm her. My fellow highwaymen and I are going to ravage her, slit her throat, and then dump the wench in the river!”

“Stop it!” Arista shouted. “You’re being cruel!”

“No, he’s not,” the one who hadn’t dismounted said. He wore a hooded cloak, and with the setting sun at his back, Reuben couldn’t see his face. “He’s being stupid. I say we hold her for ransom and demand our weight in gold!”

“Excellent idea,” the younger of the two brothers declared. He had already sheathed his sword, pulled a wedge of cheese from his pack, and offered it to the mounted one, who took a bite.

“You’ll have to kill me first,” Reuben declared, and the laughter returned.

Reuben swung again. His opponent deflected the attack, his eyes locked on Reuben’s face. “That was a little better. At least that might have hit me.”

“Mauvin, don’t!” the princess shouted. “He doesn’t know who you are.”

“I know!” the boy with the wild hair yelled back, and laughed. “That’s what makes this so precious.”

“I said stop it!” the princess demanded, riding forward.

The boy laughed again and swung his sword low toward Reuben’s feet. Reuben had no idea how to counter. He thrust his blade down and in fear pulled his feet back. Off balance, he fell forward, driving his blade into the dirt. Rolling to his back and scrambling to his feet, he discovered the boy held both swords. Again laughter erupted from them all—except Arista.

“Stop it!” she shouted again. “Can’t you see he doesn’t know how to use a sword? He doesn’t even know how to . . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...