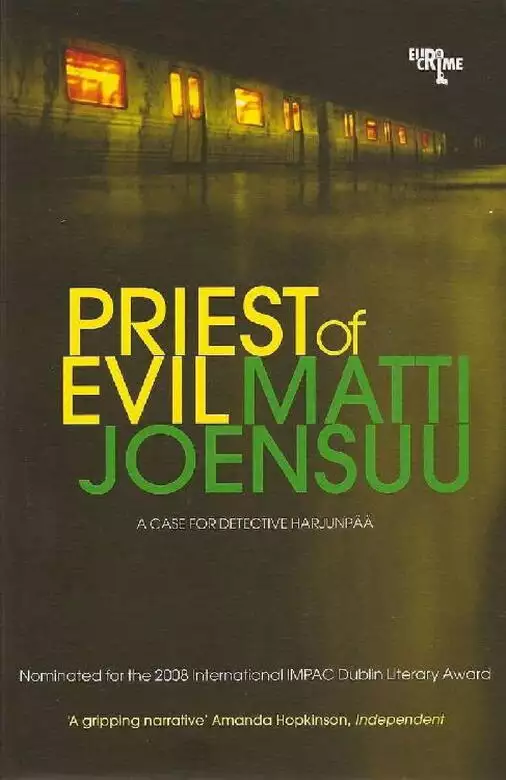

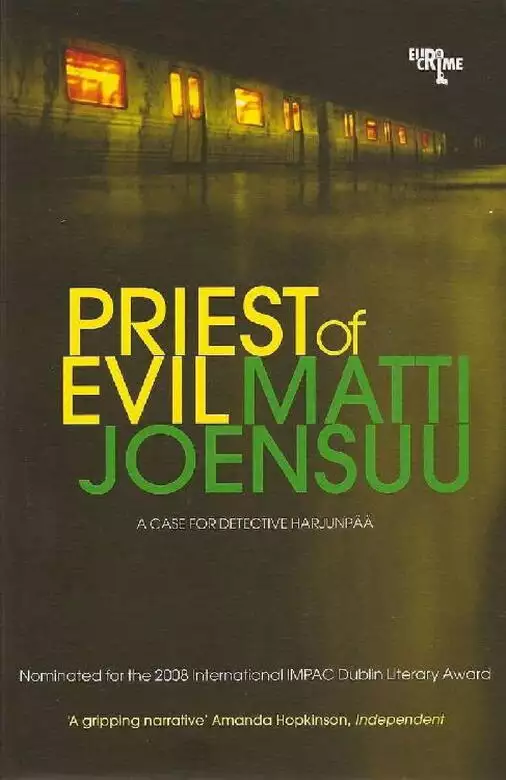

The Priest of Evil

- eBook

- Paperback

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

There is nothing more chilling than a mysterious murderer who is never seen, even by the cameras.

After a strange succession of deaths at Helsinki tube stations, the police are baffled: no one has seen anything and the tapes from the CCTV show nothing. Detective Sergeant Timo Harjunpaa of the Helsinki Violent Crimes Unit has seen more than enough of the seamier side of human nature in his career, but the forces of evil have never before crossed his path in such an overwhelming fashion. It emerges that his adversary is a deluded but dangerous character living in an underground bunker in the middle of an uninhabited Helsinki hillside. Detective Sergeant Harjunpaa must now face his most terrifying case yet.

Release date: July 8, 2008

Publisher: Quercus Publishing

Print pages: 352

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Priest of Evil

Matti Joensuu

But he didn’t answer. He didn’t want to.

‘Mikko!’

He didn’t want to be Mikko again, clutching terrified at someone’s legs or round their neck; he didn’t want to keep watch at the door any longer, because it was nasty and said bad things. All he wanted to do was curl up on top of the dressing table in Anitra’s nest and be her fledgling, because Anitra was nice: she never pecked at him, she didn’t scratch his bottom or pull his willy, and she allowed him to stroke her feathers, and that made him happy, almost as happy as when he was allowed to eat candyfloss.

Candyfloss always made him shiver slightly – like when he’d gone to the park without permission, or when on the first of May their taxi had run over a pigeon and its eye had popped out of its head, and Kasper had poked the end of Tuija’s hat into its beak. It had stared at them the way Father’s cigarettes stared at them through the night-time darkness. The feathers made him feel like Anitra was his real mother, and that Mother was only a pretend mother, some unknown, naughty boy’s nagging mother. And again he felt a shiver, the same kind of chill as when someone pulled his hair, and he began thinking of the legs beneath the dressing table: dark-green lion’s paws, complete with claws and everything. And even though they were made of wood, nobody dared tiptoe past them, not even the fat janitor with smelly hairs growing out of his ears.

‘Mikko!’ someone shouted again, then came another yelp: ‘Are they killing each other yet?’

He was the one, he, Mikko, and all at once he sat up – there was no nest, no candyfloss and no Anitra. Nothing good ever came true. It was still dark, still night, the same wicked night. He ran his fingers along the bed and his pyjama trousers – of course: he had wet himself again, though this time there was only a little bit; it would dry out by morning and he wouldn’t have to fetch the belt from the kitchen. It was hanging on a towel hook by the door, so high up that he had to use a chair to get it down.

‘Not yet,’ someone whispered near him; and it was then that Mikko saw him and quickly drew his arms and legs back inside the safety of the blankets. It was the skeleton man, he had a white face and white hands, you couldn’t see anything else of him, and presumably there was no flesh on his bones either. He even smelt like nothing but bare bones, and Mikko could feel his heavy stare through the black holes in his face. ‘Mikko?’ he whispered again, his voice sounded like Marja’s after she had been bawling, as though he was sucking a boiled sweet. His head nodded to one side: tick-tack! It was Marja after all.

‘But Dad’s got three cigarettes in his mouth and another one burning in the ashtray, you know, pacing back and forth… It’s your turn.’

‘Let’s go together.’

‘It’s your turn.’

‘You can have my frog man.’

The alarm clock ticked and its hands moved ever so slowly. Someone flushed the toilet on the floor downstairs, even though you weren’t supposed to do it at night, and a car drove past on the street outside casting a strange light on the ceiling, like a mitten without a thumb; it turned slowly on to its back and flowed down across the wall, but never quite reached the floor. Marja’s nose began to run and she secretly wiped it on the sleeve of her nightgown.

‘I’m so tired!’ she sobbed into her hands so as not to wake Saara, she would have started to cry too. Marja knew how. So did he, they had both learnt. ‘My tummy hurts and I have to go to school in the morning. You don’t!’

‘Marja, please!’ said Mikko, startled; it always scared him when Marja started crying. She was so grown-up, already in the second year at school. He took Rum-Rum by the hand and clambered on to his feet. The floor felt terribly cold beneath his toes, like a tin sheet the dogs had weed on during the winter. He took hold of his sister and they hugged, lulling each other as if they were dancing, and for a brief moment Mikko felt happy again; perhaps no one would die after all, and come the summer he and Uncle Eikka would be able to go canoeing round the lake again.

‘I can watch him by myself,’ Mikko finally tried to pluck up some courage, though his lips trembled like when he said bad words and had his mouth scrubbed clean. ‘You can have the frog every now and then.’

‘And you can have my bouncy ball, but only for a while. Come and wake me up if they start, but if not wait until the alarm goes off. Two o’clock, mind, not half past one.’

‘OK.’

‘Good night,’ she whispered. There came the patter of her toes across the floor, a rustling as she crawled into bed, followed shortly by a soft murmur: ‘Now I lay me down to sleep; I pray Thee, Lord, my soul to keep. If I should die before I wake, I pray Thee, Lord, my soul to take; and this I ask for Jesus’ sake. Amen.’The sheets rustled once more as she turned on to her side, then everything fell quiet. Nothing could be heard but the sound of Saara quietly sucking her dummy.

Mikko was alone.

He didn’t want to look anywhere.

At night his home seemed strange. Even its heart was black, though he knew that only wicked people have such a thing – and they don’t go to heaven. And he knew that the table had disappeared again, and that in its place there lurked a smelly bear; he knew that three zebras were standing in front of the closet, pretending to cover their eyes, but it was all a trick. They were staring out between their fingers and would start whinnying if he looked at them. The bear would fly into a fury if someone looked at him; Mikko didn’t dare so much as glance at any of them.

But he did notice one thing: the waste bin was full of little balls again – and this frightened him. He pulled his lower lip between his teeth and began biting it. It frightened him because he knew that they weren’t really balls at all: they were the heads of little children. God had killed them.

‘Marja,’ he whispered, so quietly that only his lips moved. He waited for a moment, and when the silence continued he turned around. Light shone in from the hallway, but it wasn’t good light; it was bad, as though someone were holding a dirty hand in front of a lamp, and Mikko didn’t want to go out there. When he tried to walk out there he felt even more of a chill, so much so that he shivered. He held Rum-Rum against his face; he was shivering too and his eyes were wet. Mikko hushed him, stroked his bare back and whispered into his ear – perhaps it was in Swedish or some other foreign language, because he couldn’t understand a word of it.

A moment later he was in the doorway; almost as if he had moved without his noticing, but there he stood nonetheless. Now there was slightly more light, and although he had heard the voices all along, now he could make them out properly. The air was full of them, like angry, squawking birds. ‘Answer me, God damn it! Was this in your pocket or not?’

‘I’ve already said, I don’t want to talk about this any more!’

‘You’d better believe we’re going to talk about it – we’re going to talk about it so we’ll never have to talk about it again!’

‘What the hell do you go rummaging through other people’s pockets for? You’re such a stupid cretin that you can’t even see that it’s only a sample. A bloody sample that I got in the post!’

‘Of course, how stupid of me. Condoms come through the post every day…’

‘Oh give it a rest, for Christ’s sake. How should I remember? It could just be one of the boys at work, their idea of a joke.’

‘That’s right. You’re a joke of a man! Is it that whore Hännikäinen? Is it her again?’

‘Stop it, for crying out loud! Stop it!’

Mikko was right behind the door. Light was oozing through the doorframe; it was yellow like wee. Through the doorframe came the smell of cigarette smoke and very bad words.

On the other side of the door was the kitchen – and Mother and Father. They were the ones bellowing at each other. Yet at the same time they weren’t like Mother and Father at all; they seemed strange, a pair of raging hooligans. His lips pursed together as he thought about it: what if they stayed like that? All at once he could feel a swarm of little yellow ants tingling in his cheeks and his stomach began to churn, and he could feel invisible ropes dragging him down to the floor. He began to feel very tired and almost wanted the ropes to win.

‘Stop fidgeting with those cigarettes, you moron! You’ll burn the house down.’

‘Fine, I can finally get rid of the wife and kids – everything! And I’ll sure as hell…’

‘You’ll what? That’s right, threaten to kill us all again.’

‘You keep your trap shut, woman!’

‘Oh it’s my fault, is it? Kill me then, I’d be better off dead than stuck here while you’re out with your whores.’

‘Whores!’

‘Kill me, go on, kill me!’

‘You can be sure I will!’

Chair legs screeched across the floor, there came a sound like the roar of a beast; something clattered and smashed on the floor. Mikko imagined the kitchen to be full of spears flying through the air, sharp spears that sailed through people, shattering them to pieces. He realised that he would have to go and wake up Marja, because they had to save Mother and Father, that was their job; but just then he remembered the Cupboard Monster. He froze and couldn’t take another step. Cold, sticky drops of sweat trickled down through his hair.

At night it lurked in the hall. During the day it hid inside the wall – it could even eat stone – and that’s why Mikko had never seen it. But Marja had seen it, many times. One night it had almost caught her as she was on her way to the toilet. It was a bit like a dachshund, but didn’t have paws or a tail. First it would spit poison into your eyes making them sting, blinding you. Then it would crawl under your skin through your bottom or the soles of your feet and start eating your flesh, and then there was nothing you could do but cry out. Finally it would eat your heart, chewing it slowly, and then you would die.

Mikko let out a short frightened gasp. He sensed that it was right behind him. He could even hear it making noises, he tilted his head – yes, at that moment he was absolutely sure of it – it sounded as though something was crawling across the floor, panting, and he couldn’t think what to do. At last he shut his eyes tightly, pressed his hands against his bottom and began raising his feet off the ground, one at a time, high into the air – he was almost flying – and he wished with all his heart that Mother and Father would notice him and come to his rescue. And all the time, barely audibly, he whispered: ‘Mummy, Daddy, Now I lay me down to sleep, Mummy, Daddy…’

‘Mikko! Mikko!’

‘What?’

‘What are you dancing about for?’ Marja demanded and smacked him across the shoulders so hard that it stung. She had switched on the hall lights, and now there was nothing on the floor but shoes and a rug. ‘Why didn’t you wake me up? Are you deaf?’ Only then did Mikko notice the constant clattering coming from behind the door, the angry grunting and shouting, and for a moment he was sure that it was a bear, but then he gradually began to make out the ‘fucks’ and the ‘bastards’, when amidst it all his mother cried out: ‘Help!’

Marja wrenched the door open; the air was blue, chairs lying across the floor; a row of cigarettes lay smoking in the ashtray, a thin, curly tail rising from each of them into the air. Mother was lying on the floor. Her face was red. Father was sitting flat on top of her, his hands around her throat. Marja nudged her brother and a moment later they were in the thick of it, trying to drag Father away. Mikko pulled at his shirt while Marja tried to prise his fingers loose. Buttons popped out like teeth, there were arms and legs everywhere, and all they could hear was ‘Help!’ and ‘Bastard!’ Somehow Mikko found himself at the bottom of the pile; he couldn’t see a thing and couldn’t move – he could hear nothing but the screaming and could smell Father’s sweaty back.

Suddenly everything stopped.

Mikko didn’t understand quite how it had happened, it simply stopped. This had happened before. He rubbed his face and rose to his knees. Father was already on his feet, pacing about the room gasping for breath. A glob of spit or snot hung at the side of his mouth; Mikko tried not to look at it, he was ashamed, ashamed of everything. Father was so big; his head reached almost as high as the lamp, and as he paced back and forth across the room he resembled some kind of killer robot, building in speed. When he was angry his face became terribly ugly, like a bony tortoise that could bite everything to pieces.

‘My poor darlings,’ Mother started to wail. Now she too was standing up, spluttering and trying to clear her throat. Mikko gave a start – he already knew what she was going to say, though she ought not to. Marja knew too and cried out somewhere behind him: ‘Mother, no! Please stop, Mother!’

‘My little darlings,’ she moaned on and on. Perhaps she too was genuinely afraid because her shoulders were shaking. ‘Your Father’s going to shoot me…’

‘The pistol!’ Father bellowed almost straight away: the beast had roared again. Mikko pressed his arm against his forehead so that he wouldn’t have to watch it. ‘Where’s the pistol? The pistol! God help me, I’ll shoot you all!’

This time Mikko didn’t burst into tears. He just looked at Marja, and she looked back at him, they both knew. Marja dashed into the hall and made it to the bureau before Father had even turned round. A second later Mikko was at his legs. He clasped his arms around Father’s ankles, grabbed at his trouser legs until they lay in a bundle at his shins, but still Father hobbled towards the living room, his slippers booming against the floor. The cork flooring shimmered like thicket in Mikko’s eyes, the door jamb struck his knees with a sting; the hall rug became tangled beneath them; shoes fell into the corner with a clatter. Amidst all the commotion something clinked like a ship’s bell.

‘Marja!’ Mikko whined, repeating his sister’s name over and over, as he felt that he couldn’t hold on much longer, that his hands were already so numb that they ached. He thought he could hear Marja shouting back that she had got there in time. At that he loosened his grip on Father’s legs and lay sprawled on the crumpled rug. Through his panting he could hear Father rattling the bureau and swearing, but there was nothing he could do about it. Marja had hidden the key just in time.

Mikko lay still, he was afraid. For it didn’t stop there, it never stopped there, because Father became all the more angry when he couldn’t find the pistol and shoot them all. He lay perfectly still, so still that it almost felt as though he didn’t exist, as though he were almost dead, and he was certain this would make Mother and Father very happy, because in some way everything was always his fault. Perhaps they had been arguing about the fact that he still hadn’t learned to get up in the night and use the potty. That was why they called him Mr Piss Pants.

Very cautiously he raised his head. Father was already rushing towards the window. In a flash his hand was on the latch; he turned it and pulled it open. The outside air flooded in; it was like water. Father was lying on the window ledge, but thankfully Marja was holding him by the belt. Mikko dashed over to help and somehow he managed to clamber on to Father’s back and pull him inside – or so it seemed, at least. A red neon sign flashed on the building opposite, but he couldn’t make out all of its letters yet.

‘Erkki!’ came Mother’s voice. ‘Erkki, please!’

At that everything stopped again, just as it had in the kitchen, as if by magic. The radiators seemed to have stopped rattling. No one said a word. No one looked at anyone else. Only Saara cried in the bedroom, wailing at the top of her lungs. Mikko could see her in the mirror standing up in her cot, white as a rabbit, holding on to the bars with both hands. There came a rustling sound as Father dug in his pocket for a cigarette. Mother snapped: ‘Look what you’ve done, you little brats! You’ve woken up your sister. You should both be ashamed! Who gave you permission to get out of bed? Marja, go and get your sister back to sleep. Mikko: toilet, then straight back to bed like you’d never got up.’

Mikko plodded back to Rum-Rum. He was lying on the hall floor, broken. He didn’t have the strength to say his evening prayers, he was so tired, but he hoped that God would forgive him this once.

If someone were to claim that right in the middle of Helsinki there stood a bare mountain, and that you could walk straight through it without possessing the slightest supernatural powers – not to mention the fact that that mountain’s name was The Brocken and that inside the mountain there lived an earth spirit – he would undoubtedly be considered rather odd.

But without due cause, however, for this was almost true. No one knew about it, or rather, no one knew it to be a mountain, despite – like tens of thousands of commuters – seeing it every day, morning and night.

Perhaps the name ‘mountain’ was a bit too flattering, though a mountain was what it most resembled. Its sides were particularly mountain-like: steep, almost sheer, uneven and rocky. Dotted about the rock face were the marks left by drilling and quarrying. The mountain’s height varied between fifteen and twenty metres depending on the precise spot; it was almost three hundred metres long and about a hundred or so metres wide. It narrowed to a point at both ends, making the whole structure resemble a diamond-shaped boiled sweet.

On a map of the city it could be found on page fifty-two, in square DJ/78. Yet on the map it was only a patch of green grass, barely the size of a fingernail. Neither had it been given a name, but then again surveyors and cartographers did not know it existed either.

The page in question showed Pasila. And Pasila was indeed where the mountain was to be found, between East and West Pasila, perhaps slightly more to the east, where the two central train lines finally divided. There it rose majestically, a lone rock castle, surrounded by trains speeding in all directions, a place nobody ever had recourse to visit.

The claim that you could walk right through the mountain was also true. From behind the Hartwall Arena ran a bridge that, after it had crossed the tracks, began to slope downwards until it eventually formed a tunnel through the mountain. This tunnel came out at Ratapihantie right in front of the city exhibition centre.

If someone were to reach the top of the mountain, they would notice that the view was much the same as from the islands in the archipelago: rolling rock faces and promontories, muddy hollows sprouting with yellowed hay and moss, brittle birches, alders and ancient, resilient dwarf spruces.

At the southern face of the mountain there was evidence that the site had once been very significant indeed. A trench about twenty metres long, now partly filled with soil, had been hewn into the side of the rock. At one end the trench led to a concrete bunker inside the quarry – perhaps this had been planned as a bomb shelter for a handful of people – while the other end of the trench wound its way round beneath a concrete platform propped up on pillars several metres high. A set of concrete steps led up to the platform and if you climbed them you could see that a rail of piping ran round the edge of the slab, with rusted mounting bolts set into the floor forming two circles next to one another. One could only guess at what this had once been – something to do with anti-aircraft defence during the war; perhaps a spotlight or two.

Almost halfway up the mountain, hidden among the thicket, was a more recently erected shack made of corrugated iron, like a flat-roofed cabin with no windows and no door. At first you could not really tell what the purpose of this was either. But if you peered inside through the eaves you could see that the surface of the walls had been replaced with heavy steel mesh, and if you listened carefully, you could make out a faint, distant murmur, as if the mountain itself were breathing. This construction must have had something to do with the bunker underneath the mountain; if you were able to gain access to the railway yard and have a look around, you would soon notice two hefty steel doors at the foot of the mountain.

Standing at this corrugated iron shack, you would finally realise that, despite everything, there were visitors to the mountain every now and then: its walls were so covered in graffiti that not even by scratching it could you reveal its original colour. And if you were to examine the area more closely you would just be able to make out a path winding away from the shack down towards the northern end of the mountain. At that point the rock face was at its lowest and the incline at its gentlest, the easiest place to climb up. Still, in order to get there these daring graffiti artists would have had to negotiate their way across the central train line, moving dangerously close to the power cables at the transformer station, and climb over sturdy mesh fences.

The ground was covered in junk, the same rubbish that was to be found in the forests around any city: broken glass, empty spray paint cans, pieces of cardboard and plywood. Somehow even a child’s red slipper had ended up here. However, this rubbish did not seem particularly fresh: it was faded and rusted, having doubtless lain there as the snows of many a winter had fallen and melted.

There was a strange atmosphere on the mountain. So that no matter how badly you had wanted to go there, and even if you’d managed to arrive in one piece, you’d just want to turn around and leave. Fast.

And if you happened to look closely at the mountain from the platforms at Pasila station, as night began to engulf the blue dusk and the streetlights came on, with a bit of luck you might have been able to make out some faint movement. Just like now: it seemed as though someone had climbed up the steps and was now standing on the concrete platform above, motionless.

Killing a person was not difficult, no more difficult than killing a pigeon. All it required was a soft push – at the right time, of course, and in the right place. He of all people could sense when the time came, or rather in a mysterious way the time and place were revealed to him, and that was it: flesh was torn from the bones, guts smattered across the gravel floor, vertebrae and joints were cast about like beans, and the soul departed from the degenerate body that turns people into a devil of greed. Of course, he knew thi. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...