- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

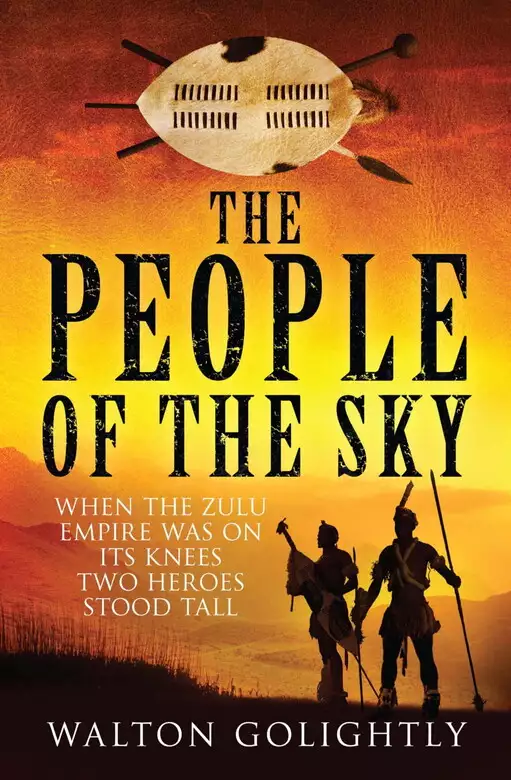

Synopsis

1828. King Shaka has survived an assassination attempt. Important trade routes have been secured. Yet all is far from calm in the Zulu Empire... The bulk of Shaka's army toils in the diseased swamps of Mozambique; the white men at Port Natal have begun disobeying his laws; and enemy tribes are slowly infiltrating Zulu territory. Both king and kingdom are more vulnerable than ever. With Shaka increasingly withdrawn, it falls to the Induna - his most loyal warrior - and his trusted sidekick, to quell this disquiet. And thus begins their adventure... The duo must solve mysteries, brave battles and shed blood - and in the process face off against bandits, thieves, slavers, cannibals and plotting princes - if their magnificent kingdom and its ailing creator are to stand a chance of enduring.

Release date: February 28, 2013

Publisher: Quercus Publishing

Print pages: 592

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The People of the Sky

Walton Golightly

They were Abantu – Human Beings – and all other tribes they regarded as wild beasts, savages, izilwane.

We have heard how an heir to the Zulu throne, Senzangakhona KaJama, made a female of the Langeni tribe pregnant. It was Ukuhlobonga, he said, the Pleasure of the Road: a dalliance between clenched thighs; if both of you lost control and penetration occurred, a fine of a few cattle would appease the girl’s father and she’d still be regarded as a virgin.

With Jama ailing and close to death, his brother Mduli all but ruled the small tribe in his stead. And there was now a problem.

As the enraged elder told his nephew, this was not a matter that could be resolved with a few cattle. For the Langeni were the home tribe of Senzangakhona’s mother and, in getting one of their females pregnant, the young fool had committed incest in the eyes of Zulu law.

Mduli’s only recourse was to deny everything. ‘You say she is pregnant,’ he told the Langeni delegation that had been despatched to the Zulu royal kraal at Esiklebeni. ‘I say impossible! You say her belly is swollen with the seed of a Zulu King. I say rubbish! This female is ill.’

Her swollen belly, he declared, was caused by a stomach beetle called a ‘shaka’.

‘That is what’s in her gut,’ sneered Mduli. ‘A shaka!’

Fine, said Nandi – the ‘afflicted’ maiden in question, whose name meant ‘Sweet One’– and when her son was born she named him ‘Shaka’. Now here is your Beetle, said her family. Come and fetch him! And his mother too, for they were only too happy to be rid of the wilful girl.

Senzangakhona was by then King and was told by his uncle that he no longer had any choice in the matter; it would be better to hush up the affair. Reluctantly, the new King took Nandi as his wife. No lobolo, or bride price, was asked for or paid – a mark of shame; a sign of how little Nandi was valued even by her own family.

Years of abuse and cruelty followed. And things didn’t get better when Nandi and Shaka were sent off to live with his mother’s people. As if the scandal of the ‘banishment’ wasn’t bad enough, Shaka’s insistence on his being the heir to the Zulu throne saw him mocked and bullied by the other local boys, while their parents shunned Nandi. She had brought this all on herself, they said. She had tried to seduce a Zulu prince and failed – and yet still acted as if she were a queen. Finally it became too much and they left the Langeni, to live like beggars seeking succour wherever they could.

In 1802 came the great famine of Madlatule – Eat and Be Quiet – and they almost starved to death as they roamed the dying land. Yet always, amid these hardships, their bellies howling, Nandi would hug her son tightly and tell him: ‘Never mind, my Little Fire, never mind. One day you’ll be the greatest King in all the land.’

Finally, when Shaka was eleven, they went to live with a clan of the Mthethwa tribe – and their fortunes began to change for the better.

Meanwhile there was one other who joined Mduli as the power behind the Zulu throne. This was Senzangakhona’s elder sister, Mnkabayi – and it was said that, aided by her loyal induna, Ndlela KaSompisi, this wise and powerful woman had been dabbling in Zulu politics – such as they were – even while her father Jama was alive. Whatever the case, she and Senzangakhona were particularly close and she could be counted upon to make sure that, as far as possible, her brother lived up to his name as The One Who Acts Wisely.

She was also feared by the tribe’s sangomas, who were led by a certain Nobela at that time and who constantly sought to exert their influence on the Zulu Kings.

Aiee … that old crone, Nobela! Even though she never sought to exercise her authority over the others openly there was no doubting she held them in her thrall, and Mnkabayi’s hatred of her knew no bounds. Which wasn’t surprising since Nobela was one of those who had wanted Mnkabayi dead before she’d even suckled her mother’s breast.

It had to be Nobela told Jama, if he was to save himself – and the tribe – from the curse that accompanied twins. In an act of courageous obstinacy, however, Jama decreed that Mnkabayi, who had left her mother’s womb first, and her sister Mmama would both be allowed to live. Anyone who sought to harm them would have to face his wrath.

Mmama died while still an infant and, although her immediate family then treated her just like any other child, Mnkabayi would never forgive the sangomas.

Ironically, this very antipathy saw some seek her patronage. And these creatures made good spies.

We have heard of the warrior Godongwana, who at a young age revealed the traits that would one day make him a great ruler, and how his jealous brothers managed to persuade their father Jobe that Godongwana was plotting to overthrow him. Upon receiving a summons to Jobe’s kraal, Godongwana chose to flee rather than see his father shame himself by believing the lies of others.

Finding himself among the Hlubis, people of Xhosa stock, he soon distinguished himself through his bravery and initiative and became a headman in the tribe. One day, a White Man came to his kraal who was likely the last survivor of an expedition despatched from the Cape in 1807 to find an overland route to Portuguese East Africa. Having heard that Jobe had died and deciding it was time to return home to claim his birthright, Godongwana agreed to guide the man to the coast, but en route the stranger contracted a fever and died. Godongwana never forgot the White Man, never forgot the things he’d spoken about as they sat around the fire of an evening.

For, coming from the Cape, the White Man could speak Xhosa, a Nguni language Godongwana understood, and the young prince could grasp most of the concepts he raised – trade, empires, wars of conquest. It was the sheer scale of such concepts that awed him. And got him thinking.

It was the White Man, Godongwana later said, who gave him the idea of uniting the tribes in the region. But it wasn’t to be conquest for the sake of conquest, for Godongwana envisaged what was in effect a commonwealth that would be able to deal with the White Men on their own terms. For that was something else the White Man told him: the Long Noses were coming, and in greater numbers than he could ever imagine. And their actions would gradually begin to impinge more and more on ways the tribes thought were timeless and immutable.

After burying him, Godongwana took the White Man’s gun and horse and returned home. He was a dead man come to life, reborn and renamed – for he now called himself Dingiswayo, the Wanderer, and cut a fine figure with the horse and rifle. It mattered not that the horse soon died, for these were not healthy environs for naked zebras, or that the gun was next to useless, lacking ball and powder. They were still powerful talismans, and few had the courage to dispute his claims. Here was a man truly blessed by the ancestors.

The year was 1809 and it was Dingiswayo, not Shaka, who first set about uniting the tribes and clans on the south-east coast of Africa, organising something approaching a standing army, and fighting wars not only to increase his herds but to gain – and hold – territory, so as to secure the trade routes with the Portuguese in Mozambique. The Zulu King merely completed what his mentor had started.

A brave warrior with some outspoken notions as to how battles should be fought, Shaka would have come to Dingiswayo’s attention sooner or later. That their relationship should soon deepen into something beyond mere respect and admiration, however, wasn’t surprising. It’s likely that Dingiswayo saw in the young Zulu a kindred spirit, a fellow outcast.

And in 1815, the ruler of the Mthethwas persuaded an ailing Senzangakhona to acknowledge Shaka as his heir. When, on his deathbed, the Zulu King reneged on his promise, selecting his son Sigujana as his successor instead, Dingiswayo sent the elite Izicwe regiment with the twenty-eight-year-old Shaka to help set matters right.

In this, Dingiswayo, Shaka and Nandi were assisted by Mnkabayi. Sigujana had already proved himself to be a dissolute ruler whose reign did not bode well for the future of the tribe, and Mnkabayi’s endorsement of Shaka’s claim went a long way to assuaging any doubts the people might have.

At the same time she persuaded Nandi to stay Shaka’s hand, should he contemplate removing his other brothers – especially Dingane who, as next in line, could be expected to plot against this usurper who had spent so much time among the Mthethwas that he could barely speak Zulu.

In turn, following his aunt’s orders, Dingane surprised everyone by acknowledging Shaka as King and swearing fealty when the two finally met. This was the final endorsement the nation needed and, that day, cries of ‘Bayede, Nkosi!’ Hail to the King! ‘Bayede, Nkosi, bayede! Bayede!’ rang out around the sacred cattlefold.

A short while later Shaka set about slaughtering those who had been unkind to Nandi. Mduli, the cantankerous uncle who had sent Nandi’s relatives packing, was among the first Shaka saw put to death. But it’s said he asked to die like a warrior, with an assegai thrust, and went to join the ancestors praising Shaka’s greatness, for he had looked into Shaka’s eyes and seen there everything Senzangakhona’s other sons lacked.

Chances are that Mnkabayi herself would have been spared even if she hadn’t played an active role in helping Shaka to seize the throne. Her noble upbringing – a willingness to grit her teeth and endure Nandi’s tantrums – had seen her treat Nandi far better than her brother’s other wives had done. And Shaka came to treat her as a veritable queen, second only to Nandi, entrusting to her the care of his great northern ikhanda, or war kraal, which was the Sky People’s most important settlement next to KwaBulawayo.

When his impalers had finished with the members of the Zulu court, Shaka took his wrath against the Langeni, Nandi’s home tribe, punishing those who had shunned Nandi and mocked him.

At the same time he set about reorganising the Zulu army.

And we have heard how he introduced his men to the iklwa – a short stabbing spear used in an underarm motion, much like a Roman broadsword. Why, he asked his men, would a warrior want to divest himself of his weapon in combat? That each man might be equipped with four or five long spears mattered not a bit. All were for throwing, which meant throwing away, thus leaving one with nothing with which to defend oneself. Aiee! What foolishness!

With the help of Mgobozi, the Mthethwa warrior almost twice his age who had fought alongside Shaka in the Izicwe legion – and who had decided to remain behind to serve the King – Shaka set about training his men in how to use the iklwa.

What they could throw away, he decreed, were their sandals because, invariably ill-fitting, these made a warrior clumsy. From now on Zulu warriors would march and fight barefoot, and Shaka sent his men back and forth barefoot across thorns to toughen their feet. (In later life, though, whenever he came upon a shattered terrain littered with sharp rocks, Shaka would order a pair of sandals made for him.)

Following Dingiswayo’s example, Shaka also proceeded to reorganise the Zulu amabutho, or regiments, according to age-sets, as a way of improving discipline and defusing any potential threat the army would have for himself, or his plans.

Previously, local chiefs had been responsible for sending men to the King whenever the need arose. If they were opposed to a campaign, they’d send fewer men than were actually available, claiming that’s all they had. Even if a chief condescended to despatch all the men he could muster, they remained primarily loyal to him. They were still his men and therefore more likely to do his bidding than the King’s.

By creating his regiments according to age rather than region Shaka changed all of this. Males born within the same four-year period would be summoned to Bulawayo from across the kingdom and formed into a fighting unit with its own name and unique shield markings.

Regional and clan loyalties were thereby negated. While in training or on active service the regiments were stationed at the amakhanda, the war kraals sited in areas of strategic importance. Thrown together, each far from home, but of the same age, the men were soon referring to themselves by their regimental rather than their clan names.

However, Zulu custom threatened this cohesion. Once a man married he was allowed to leave his regiment and return to his clan lands to establish his own homestead. This, of course, brought him back under the sway of the local chief. Shaka’s solution was to withhold permission for his warriors to marry while he was consolidating his own power.

The Ufasimba – the Haze – was the first regiment trained in Shaka’s methods from the start of its career, and it would become his favourite ibutho.

Warriors at this time were expected to forage for themselves and therefore another important innovation the new King introduced was having twelve- and thirteen-year-old boys accompany the soldiers, carrying rations, water gourds and sleeping mats. One boy would look after three or four warriors, while indunas – senior officers – would have an udibi to themselves.

We have heard how the uneasy peace that gave Shaka time to begin training his men and form his new amabutho ended when Zwide, King of the Ndwandwes, fell on Matiwane and his Ngwanes, killing men, women and children and burning their kraals. Only the precious cattle were spared. When Dingiswayo angrily demanded the meaning of this massacre, wily Zwide claimed he’d received news that the Ngwanes were plotting against Dingiswayo and had attacked them before they could bring their plans to fruition.

The Wanderer wasn’t fooled, and Zwide sent his sister to soothe the Mthethwa monarch’s anger. She also stole his seed, it’s said, and the Ndwandwe medicine men went to work. For a King’s semen was regarded as the source of his power, and thus Dingiswayo was cursed.

Meanwhile, Dingiswayo called upon his allies and moved on the Ndwandwes. Although he had bested a few clans who saw in the Zulus easy pickings, Shaka felt his army wasn’t ready and his powerbase still insecure, but he had no option but to obey his mentor’s summons.

However, the curse was already working. The Mthethwa army halted close to KwaDlovungu, Zwide’s capital and, while waiting for his allies to join him, Dingiswayo went out scouting, accompanied by five female bodyguards, and was duly captured by a Ndwandwe patrol. The small group was escorted to KwaDlovungu, where Dingiswayo was cordially received by Zwide, who slaughtered an ox in his honour.

The following day, the ruler of the Mthethwas was executed, and his head was removed so that Zwide’s mother, Ntombazi, could add another King’s skull to her collection.

Left in disarray, the Mthethwa army was easily defeated. The only reason why the Zulus did not become involved was because Shaka and his men were intercepted by a messenger from Dondo of the Khumalos, who told them what had happened and enabled Shaka to withdraw his army.

Zwide, who knew of Shaka’s achievements, especially against his own legions, and also knew he was Dingiswayo’s favourite, saw this as an act of cowardice and resolved to leave the People of the Sky until last – when he had finished devouring Dingiswayo’s other allies.

When Zwide finally sent his army against Shaka, the Bull Elephant was ready for the clash. ‘Know this, my children: we fight for our lives!’ he told his regiments shortly before the battle. ‘Death is the only mercy we can expect!’ Zwide was coming for their women, their children, their cattle! ‘But we have his measure,’ said Shaka. ‘Let him come, and he’ll encounter a tempest the like of which this land has never seen. This land …’ The King spread his arms. ‘Do this, defeat these lice, and this awaits you! These green hills, these plains and swollen rivers! Standing shoulder to shoulder, you have the power to win this land. To rule this land!’

The Bull Elephant then had his greatly outnumbered amabutho encircle Gqokli Hill. In due course they were in turn surrounded by the Ndwandwes, who were led by Zwide’s son Nomahlanjana. But, so great were their numbers, the Ndwandwe soldiers found themselves trapped among each other, struggling for space – unable to throw away their spears, as Shaka would put it. And the Zulus attacked, then returned to their position on the slopes of the hill. And so it went for most of that day – the Ndwandwes would attack, struggling uphill in their sandals, the Zulus would repulse them, then counter-attack as they fled down the hill, before returning to their positions.

Soon thirst began to take its toll. Shaka had ensured waterskins were stored on the summit of the hill, while the Ndwandwe warriors began to wander off, ignoring their screaming officers, in search of something to drink.

The Zulus themselves had suffered many casualties – and were still outnumbered – but a final charge shattered the exhausted Ndwandwe ranks, and a slaughter ensued.

Gqokli Hill was the end of the beginning. It announced to the world – the growling, quarrelsome relatives who surrounded them – that the Sky People were no longer going to be vassals.

Other successful campaigns followed once the Zulu regiments had regained their strength, and new regiments were created and trained. At home, Shaka consolidated his power by embarking upon a campaign of a different sort against the Zulu sangomas. Because they had the Calling and so could commune with the ancestors, they enjoyed a special status and were as revered – and feared – as the King himself, who would do well to ensure he had their support. Shaka, however, made sure they knew things had changed and he was now ruler of all. All had to obey him or else have the King’s Impalers find them a new perch.

And we have heard how Zwide sent his men against the Zulus once again. This time they were led by a more able commanderin-chief, since Soshangane had been at Gqokli Hill and had learnt a lot. It was thanks to him that of the three assegais Ndwandwe soldiers carried, one was a short stabbing spear much like the Zulu iklwa – and their flimsy wooden shields had been replaced by tough oval cowskin shields similar to the Zulu isihlangu. He’d also tried to instil in his men a sense of discipline, so that columns and troop movements were now more orderly. He wasn’t sure the men were ready yet, but he had no choice but to obey his ruler.

Shaka had a spy in Zwide’s court, though, and was ready for the Ndwandwe invasion. His force easily defeated, Soshangane was allowed to go free, while the Zulu amabutho went rampaging through Ndwandwe territory. But Zwide eluded them, fleeing north with his sons, but Shaka was able to ensure his mother Ntombazi’s death was painful and prolonged.

The Sky People now controlled the trade routes – and hence the trade – with the Portuguese.

And the praise-singers, the izimbongi, sang of Shaka’s greatness: He is Bull Elephant! He is Sitting Thunder! He is Lightning Fire! Hai-yi hai-yi! I like him when he wrapped the Inkatha around the hill and throttled Zwide’s sons. I like him when he went up the hill to throttle Ntombazi of the skulls. Bayede, Nkosi, bayede! Blood of Zulu. Father of the Sky. Barefoot Thorn Man! I like him because we sleep in peace within his clenched fist. Hai-yi hai-yi! I like him because our cattle are free to roam our hills, never to be touched by another’s hand. I like him because our water is sweet. I like him because our beer is sweeter. Bayede, Nkosi, bayede!

We have heard how, before Gqokli Hill, Zwide ate up most of the Khumalo tribe. Led by Mzilikazi KaMashobane, the survivors had fled to Shaka. Time and again Mzilikazi proved his courage in battle, and he soon became one of the Zulu King’s favourites.

In June 1821, after defeating Soshangane’s invasion and consolidating his power south of the Thukela River, Shaka turned his attention to the north-west. ‘Go!’ he told Mzilikazi. ‘Go to the land of Chief Ranisi, go in my name and offer him the compliments of the Bull Elephant, then impale him on the bluntest pole you can find, let his screams ring out across the valleys as a warning to the others who would spurn our protection!’

If successful, decreed Shaka, Mzilikazi could lead his people back over the White Umfolozi to the rolling hills below the Ngome forest … They could go home! Could return to the land of the Khumalos!

This duly happened, but then some in the Bull Elephant’s inner circle, believing Mzilikazi to be too much of a favourite, whispered in Shaka’s ear that Mzilikazi hadn’t handed over all the cattle he owed Shaka as a tribute after the campaign.

Mzilikazi kicked the emissaries Shaka had sent him out of his kraal, saying: ‘If Shaka thinks I owe him cattle, let him come and fetch them!’

And still Shaka stayed his hand. But finally he gave in to the warnings of his councillors that such flagrant mocking of his authority could not, must not, be allowed to go unpunished. Finally, he sent his army against Mzilikazi and his followers, who’d left their home village to take refuge in a mountain stronghold.

And there are those who say Shaka stayed his hand yet again and allowed his favourite to make his escape. And, before finally settling in what is today Zimbabwe, Mzilikazi and his people – who would come to be called the Matabele – roamed the land to the north; a tribe of nomadic bandits practising the total warfare favoured by Shaka.

Nandi, meanwhile, wasn’t happy, for she wanted her son to find his Ubulawu.

Since the days before Malandela, the father of Zulu, one of a King’s most powerful weapons was a potion called Ubulawu – or the Froth. He’d mix the muthi in a sacred vessel at sundown, while praising the ancestors and speaking the name of the enemy he wanted to defeat.

The King always used the same vessel. But when he died it was destroyed and the heir had to ‘find’ his own vessel; a process which could take years. It was said, though, that the King would know it as soon as he saw it. Emissaries from all over the kingdom would travel to the King’s kraal with a selection of pots, hoping he’d ‘recognise’ one of them, for it was a great honour for a clan to be the one who guided the King to his vessel.

Over the decades, the vessel itself came to be called the Ubulawu, the ‘froth’ becoming of secondary importance. Eventually the Ubulawu stopped being a pot and became any artefact the King deemed a bringer of good luck – and so a potion became a talisman.

Senzangakhona’s Ubulawu had been destroyed on his death and Sigujana hadn’t had time to find his before Shaka had him assassinated.

And Nandi kept pestering Shaka to find his own talisman, but he professed disdain for the tradition. ‘Let my mighty army be my Ubulawu,’ he said.

Of more importance to him was the fact that, as Soshangane had demonstrated, the remaining tribes had begun to organise themselves better and adopt Zulu-style tactics, and even versions of the iklwa. Far more cunning would be needed in future campaigns, and it was cunning that saw the Bull Elephant destroy the Thembus which, next to Faku’s Pondoes on the coast, was the last tribe that posed any real threat to Zulu hegemony.

Meanwhile another tribe of barbarians, of izilwane, had arrived on the scene: White Men. They established a trading station on the shores of the sheltered bay they called Port Natal, and which the Zulus referred to as Thekwini. It was an ideal anchorage sheltered from the worst of the storms that made sailing along this coast so hazardous, and was marred only by a sandbar which was covered by less than a metre of water at low tide.

They claimed to serve a distant King called Jorgi who lived far, far away, but who might be a valuable ally to the Zulus. But the truth was, as members of the Farewell Trading Company, they were there to make money, trading in ivory and, it was hoped, gold.

But Lieutenant Francis Farewell, who had first conceived of cutting out the Portuguese at Delagoa Bay and dealing directly with Shaka, had a rival. Lieutenant James King – who captained (and, with his mother, co-owned) the ships Farewell had hired to explore the littoral – also recognised the potential of Thekwini.

As soon as the expedition returned to Cape Town on December 3, 1823, King got to work by writing a letter to Earl Bathurst, Secretary of State for the Colonies, seeking to broach the idea of establishing a British settlement at the bay.

He made no mention at all of Lieutenant Francis Farewell or the Farewell Trading Company.

Not surprisingly, Farewell was incensed. But then, clearly believing he could raise more money there, King set sail for England. Suddenly, Farewell had time and proximity on his side. He raised money from the wealthier businessmen in the Cape’s Dutch community, won over by his tales of cattle kraals made entirely of elephant tusks, and had an advance party on its way to Port Natal before King was anywhere near England.

And early on the morning of May 10, 1824, the sloop Julia slipped over the sandbar and anchored in the northern sector of the bay. Henry Fynn, who had arrived at Cape Town in 1818 at the age of fifteen, was the group’s leader. He was tasked with ensuring that dwellings for the main party were built and also establishing contact with Shaka.

He set about the latter with alacrity and would become one of the Zulu King’s favourites among the White Men.

Then Nandi died, and we have heard of the horrors that followed.

Over the coming months Shaka took to slaughtering whole villages of people he felt weren’t showing sufficient sadness at the passing of his mother. He forbade fornication, and had holes torn in the huts so that his slayers could come round at night and make sure this law was being obeyed. Another ukase allowed that the cows be milked but no one was allowed to drink that milk; instead, it would be thrown onto the ground.

It was as if Shaka wanted to see everyone join his mother on the Great Journey. These weren’t sacrifices, all those people put to death for failing to show sufficient sadness; it wasn’t about reminding the ancestors of her greatness. Instead, it was as if all of those who still lived were an insult, an affront – how dare they eat and drink and fuck while she lay curled up in a hole! If she couldn’t live, then neither could they!

Shaka even shunned Pampata, his favourite concubine, while Mnkabayi and the King’s prime minister, Mbopa, and others loyal to the King did their best to ensure some form of governance was kept in place. Aiee! And see how Shaka rewarded Mbopa! Just when you thought his actions couldn’t get more depraved or more spiteful. Aiee! Dingane, Mhlangana and the other brothers had trembled and slept with their spears, thinking Shaka might use this as an opportunity to thin their ranks, but see where Shaka’s madness had led him: to the kraal of one of his most trustworthy servants!

And then it was over. It was as if Shaka had been ill with a fever – because that’s how sudden the recovery was.

There were still lapses, when the King disappeared into his hut, his indlu, for days on end and no one dared disturb him, or times when every utterance of his condemned some unfortunate to death, but these became less and less frequent.

The insane laws were repealed, and the nation rejoiced.

But there were those such as Mnkabayi who, observing the King closely, came to suspect that the terrible fever had merely been the birth pains of something infinitely worse.

And we have heard how, in 1826, Shaka decreed that the Umkhosi, the First Fruits, would be conducted differently henceforth. Traditionally, the final rituals of the Zulu harvest ceremony were carried out by the various village chiefs around the kingdom as well as by the King, their ceremonies mirroring his, but Shaka announced that, henceforth, only the King would conduct the rites that concluded the First Fruits.

This would serve to centralise his power even further. Mnkabayi could appreciate that and therefore she supported the ruling, despite the disgruntlement it caused among the abanumzane, or headmen.

But why invite the White Men from Port Natal to witness these sacred rituals? That’s what she couldn’t understand. That’s what vexed her. It was sacrilegious and reinforced her belief that Shaka’s ‘recovery’ after Nandi’s death had been temporary, merely the prelude to further, more dangerous madness.

But there was more to the Umkhosi, more to the First Fruits, than a mere harvest festival. It also involved the King going into seclusion for several days beforehand. Doctored by his inyangas with Imithi Emnyama, Black Medicine, he would commune with the ancestors, seeking their blessing for the year to come. And Shaka intended to use the ability th

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...