- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

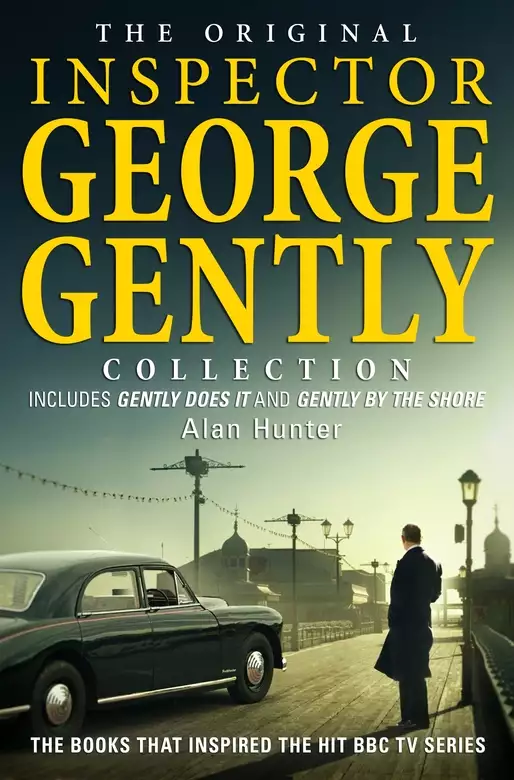

Synopsis

The first of Gently's cases, 'Gently Does It', has him enduring the holiday from hell when he is caught up in a mysterious murder and locks horns with the local police over their handling of the affair. In the second book, 'Gently By The Shore', other people's holidays are disturbed when Gently is called in to investigate the discovery of a body on a pleasure beach.

Release date: April 26, 2013

Publisher: Constable Crime

Print pages: 528

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Original Inspector George Gently Collection

Alan Hunter

It was something new in Walls of Death. It was wider, and faster. The young man in red leather overalls was not finding it at all easy to make the grade. He was still tearing madly round the cambered bottom of his cage, like a noisy and demented squirrel, trying to squeeze yet more speed out of his vermilion machine. Chief Inspector Gently watched him approvingly. He had always been a Wall of Death fan. He breathed the uprising exhaust fumes with the contented nostrils of a connoisseur, and felt in his pocket for yet one more peppermint cream.

Suddenly the gyrating unit of man and machine began to slide upwards towards him: a smooth, expert movement, betraying a brain which could judge to a hair. The ear-splitting thunder of a powerful engine in a confined space rose to a crescendo. The solid wooden wall vibrated and swayed threateningly. Higher it crept, and higher, and then, in one supreme gesture, deliberately rehearsed and breathtakingly executed, shot up to the very lip of the guard rail with a roar of irresistible menace and fell away in drunken, flattening spirals.

Chief Inspector Gently smiled benignly at the ducked heads around the guard rail. His jaw continued its momentarily interrupted champing movement. The steadying quality of peppermint creams on the nerves was, he thought, something that deserved to be better known.

Outside the Wall of Death the Easter Fair was in full swing, a gaudy, lusty battleground of noise and music. There were at least five contenders in the musical field, ranging from the monstrous roundabouts that guarded the approach from Castle Paddock to the ancient cake-walk spouting from the cattle-pens, wheezy but indomitable. All of them played different tunes, all of them played without a break. Nobody knew what they were playing, but that was not the point . . .

Chief Inspector Gently shouldered his way tolerantly through the crowd. He didn’t like crowds, by and large, but since he was on holiday he felt he could afford to be generous. He stopped at a rock-stall and inspected its brilliant array of starches. ‘Have you got any peppermint creams?’ he enquired, not very hopefully. They hadn’t, so he bought some poisonous-looking bull’s-eyes with orange and purple stripes to take back for the landlady’s little boy.

A newsboy came thrusting through the crowd, challenging the uproar with leathern lungs. ‘Lay-test – lay-test! Read abaht the . . .’ Gently turned, in the act of putting the bull’s-eyes into his pocket. The newsboy was serving a tow-haired young man, a young man still wearing a pair of scarlet leather breeches. Gently surveyed him mildly, noticing the Grecian nose, the blue eyes, the long line of the cheek and the small, neat ears. There was a note of determination about him, he thought. The peculiar quality which Conrad called somewhere ‘ability in the abstract’. He would get on, that lad, provided he survived his Wall of Death interlude . . .

And then Gently noticed the long cheek pale beneath its coat of dust and smears of oil. The blue eyes opened wide and the hand that held the paper trembled. The next moment the young man had gone, darted off through the crowd and vanished like a spectre at cock-crow.

Gently frowned and applied to his bag for a peppermint cream. The newsboy came thrusting by with his stentorian wail. ‘Gimme one,’ said Gently. He glanced over the dry headlines of international conferences and the picture of the film-starlet at Whipsnade: tilted the paper sideways for the stop-press. ‘Timber Merchant Found Dead,’ he read. ‘The body of Nicholas Huysmann, 77, timber merchant, was discovered this afternoon in his house in Queen Street, Norchester. The police are investigating.’ And below it: ‘Huysmann Death: police suspect foul play.’

For the second time that afternoon the jaw of Chief Inspector Gently momentarily ceased to champ.

Superintendent Walker of the Norchester City Police looked up from a report sheet as Chief Inspector Gently tapped and entered the office. ‘Good Lord!’ he exclaimed. ‘I was just wondering whether we should get on to you. What in the world are you doing down here?’

Gently chose the broader of two chairs and sat down. ‘I’m on holiday,’ he said laconically.

‘On holiday? I didn’t think you fellows at the Central Office ever had a holiday.’

Gently smiled quietly. ‘I like to fish,’ he said. ‘I like to sit and watch a float and smoke. I like to have a pint in the local and tell them about the one that got away. They don’t let me do it very often, but I’m trying to do it right now.’

‘Then you’re not interested in a little job we’ve got down here?’

Gently brought out the battered bag which had contained his peppermint creams and looked into it sadly. ‘They’ll send you Carruthers if you ask them,’ he said.

‘But I don’t want Carruthers. I want you.’

‘Carruthers is a good man.’

Superintendent Walker beat the top of his desk with an ink-stained finger. ‘I don’t like Carruthers – I don’t get on with him. We had a difference of opinion over that Hickman business.’

‘He was right, wasn’t he?’

‘Of course he was right! I’ve never been able to get on with him since. But look here, Gently, this case looks like being complicated. I’ve got implicit faith in my own boys, but they don’t claim to be homicide experts. And you are. So what about it?’

Gently took out the last of his peppermint creams, screwed up the bag and laid it carefully on the superintendent’s desk. The superintendent whisked it impatiently into his waste-paper basket. ‘It’s this Huysmann affair, is it?’ Gently asked.

‘Yes. You’ve seen the papers?’

‘Only the stop-press.’

‘I’ve just got a report in from Hansom. He’s down there now with the medico and the photographer. Huysmann was stabbed in the back in front of his safe and according to the yard manager there’s about forty thousand pounds missing.’

Gently pursed his lips in a soundless whistle. ‘That’s a lot of money to keep in a safe.’

‘But from what we know of Huysmann, it’s probably true. He was a naturalized Dutchman who settled down here a good fifty years ago. He’s been a big noise in the local timber industry for longer than I can remember and he had an odd sort of reputation. Nothing wrong, you know, just a bit eccentric. He lived a secluded life in a big old house down by the river, near his timber yard, and never mixed with anybody except some of the Dutch skippers who came up with his wood. He married a daughter belonging to one of them, a nice girl called Zetta, but she died in childbirth a few years afterwards. He’s got two children, a daughter who lives in the house and is very rarely seen out of it, and a son called Peter, from whom he was estranged. Peter’s known to us, by the by – he was the mate of a lorry-driver who got pulled for losing a load of cigarettes. He gave up lorry-driving after that and got a job with a travelling show.’

‘He’s a Wall of Death rider,’ said Gently, almost to himself.

Superintendent Walker’s eyebrows rose a few pegs. ‘How do you know that?’ he enquired.

‘Things just sort of pop up on me,’ said Gently. ‘That’s why they stuck me in the Central Office. But don’t let it worry you. Keep on with the story.’

The superintendent eyed him suspiciously for a moment, then he leant forward and continued. ‘Between you and me, I think Peter is the man we’re after. He’s here in town with the fair on the cattle market and according to the maid he was at his father’s house this afternoon and there was a quarrel. That was just before 4 p.m. and the body was found by the housekeeper at 5 p.m. At least, he was the last person to see Huysmann alive.’

‘As far as you know,’ added Gently mildly.

‘As far as we know,’ the superintendent corrected himself. ‘The weapon used was one of a pair of Indian throwing knives which hung on the wall. He was stabbed under the left shoulder-blade, the knife penetrating well into the heart. Hansom thinks he was kneeling at the safe at the time and the murderer had to push the body aside to get the money. The money was principally in five-pound and smaller notes.’

‘Are any of the numbers known?’ enquired Gently.

‘We’ve got a list of numbers from the bank for one hundred of the five-pound notes, but that’s all.’

‘Who was in the house at the time of the murder?’

‘Only the maid, as far as we can make out. The housekeeper had the day off till tea-time: she was out from 11 a.m. till just before five. Gretchen, the daughter, went to the pictures at half-past two and didn’t get back till well after five. There’s a chauffeur, but he went off duty at midday. The only other person with normal access to the house was the yard manager, who was watching the football match at Railway Road.’

Gently pondered a moment. ‘I like alibis,’ he said, ‘they’re such fun, especially when you can’t disprove them. But this maid, how was it she didn’t hear Huysmann being killed? People who’re being knifed don’t usually keep quiet about it.’

The superintendent twisted his report over and frowned. ‘Hansom hasn’t said anything about that. He got this report off in a hurry. But I dare say he’ll have something to say about it when he’s through questioning. The main thing is, are you going to help us out?’

Gently placed four thick fingers and two thick thumbs together and appeared to admire the three-dimensional effect he achieved. ‘Did you say the house was by the river?’ he enquired absently.

‘I did. But what the hell’s that got to do with it?’

Gently smiled, slowly, sadly. ‘I shall be able to look at it, even if I can’t fish in it,’ he said.

Queen Street, in which stood the house of Nicholas Huysmann, was probably the oldest street in the city. Incredibly long and gangling, it stretched from the foot of the cattle market hill right out into the residential suburbs, taking in its course breweries, coal-yards, timber-yards, machine-shops and innumerable ancient, rubbishy houses. South of it the land rose steeply to Burgh Street, reached by a network of alleys, an ugly cliff-land of mean rows and wretched yards; northwards lay the river, giving the street a maritime air, making its mark in such nomenclatures as ‘Mariner’s Lane’ and ‘Steam Packet Yard’.

The Huysmann house was the solitary residence with any pretension in Queen Street. Amongst the riff-raff of ancient wretchedness and modern rawness it raised its distinguished front with the detached air of an impoverished aristocrat in an alien and repugnant world. At the front it had two gable-ends, a greater and a lesser, connected by a short run of steep roof, beneath which ran a magnificent range of mullioned windows, projecting over the street below. Directly under these, steps rose to the main entrance, a heavily studded black door recessed behind an ogee arch.

Gently paused on the pavement opposite to take it in. A uniformed man stood squarely in the doorway and two of the three cars pulled up there were police cars. The third was a sports car of an expensive make. Gently crossed over and made to climb the steps, but his way was blocked by the policeman.

‘No entrance here, sir,’ he said.

Gently surveyed him mildly. ‘You’re new,’ he said, ‘but you look intelligent. Whose car is ZYX 169?’

The policeman stared at him, baffled. On the one hand Gently looked like an easy-going commercial traveller, on the other there was just enough assurance in his tone to make itself felt. ‘I’m afraid I can’t answer questions,’ he compromised warily.

Gently brought out a virgin, freshly purchased packet of peppermint creams. ‘Here,’ he said, ‘have one of these. They’re non-alcoholic. You can eat them on duty. They’re very good for sore feet.’ And placing a peppermint cream firmly in the constable’s hand, he slid neatly past him and through the door.

He found himself in a wide hall with panelled walls and a polished floor. Opposite the door was a finely carved central stairway mounting to a landing, where a narrow window provided the hall with its scanty lighting. There were doors in the far wall on each side of the stairway, two more to the left and one to the right. At the end where he entered stood a hall table and stand, and to the right of the stairway a massive antique chest. There was no other furniture.

As he stood noting his surroundings the door on his right opened and a second constable emerged, followed by a thin, scrawny individual carrying a camera and a folded tripod.

‘Hullo, Mayhew,’ said Gently to the latter, ‘how are crimes with you?’

The scrawny individual pulled up so sharply that the tripod nearly went on without him. ‘Inspector Gently!’ he exclaimed, ‘but you can’t have got here already! Why, he isn’t properly cold!’

Gently favoured him with a slow smile. ‘It’s part of a speed-up programme,’ he said. ‘They’re cutting down the time spent on homicide by thirty per cent. Where’s Hansom?’

‘He – he’s in the study, sir – through this door and to the left.’

‘Have they moved the body?’

‘No, sir. But they’re expecting an ambulance.’

Gently brooded a moment. ‘Whose is that red sports car parked outside?’ he asked.

‘It belongs to Mr Leaming, sir,’ answered the second constable.

‘Who is Mr Leaming?’

‘He’s Mr Huysmann’s manager, sir.’

‘Well, find him up and tell him I want to see him, will you? I’ll be in the study with Hansom.’

The constable saluted smartly and Gently pressed on through the door on the right. It led into a long, dimly lit passage ending in a cul-de-sac, with opposite doors about halfway down. Two transom lights above the doors were all that saved the passage from complete darkness. A heavy, carved chest-of-drawers stood towards the end, on the right. Gently came to a standstill between the two doors and ate a peppermint cream thoughtfully. Then he pulled out a handkerchief and turned the handle of the right-hand door.

The room was a large, well-furnished lounge or sitting-room, with a handsome open fireplace furnished with an iron fire-basket. A tiny window pierced in the outer wall looked out on the street. There was a vase of tulips standing in it. At the end of the room was a very large window with an arched top, but this was glazed with frosted glass. Gently looked down at the well-brushed carpet which covered almost the entire floor, then stooped for a closer inspection. There were two small square marks near the outer edge of the carpet, just by the door, very clearly defined and about thirteen inches apart. He glanced absently round at the furniture, shrugged and closed the door carefully again.

There were five men in the study, plus a sheeted figure that a few hours previously had also been a man. Three of them looked round as Gently entered. The eyes of Inspector Hansom opened wide. He said: ‘Heavens – they’ve got the Yard in already! When the hell are we going to get some homicide on our own?’

Gently shook his head reprovingly. ‘I’m only here to gain experience,’ he said. ‘The super heard I was in town, and he thought it would help me to study your method.’

Hansom made a face. ‘Just wait till I’m super,’ he said disgustedly, ‘you’ll be able to cross Norchester right off your operations map.’

Gently smiled and helped himself from a packet of cigarettes that lay at the Inspector’s elbow. ‘Who did it?’ he enquired naïvely.

Hansom grunted. ‘I thought you were here to tell me that.’

‘Oh, I like to take local advice. It’s one of our first principles. What’s your impression of the case?’

Hansom seized his cigarettes bitterly, extracted one and returned the packet ostentatiously to his pocket. He lit up and blew a cloud of smoke into the already saturated atmosphere. ‘It’s too simple,’ he said, ‘you wouldn’t appreciate it. We yokels can only see a thing that sticks out a mile. We aren’t as subtle as you blokes in the Central Office.’

‘I suppose he was murdered?’ enquired Gently with child-like innocence.

For a moment Hansom’s eyes blazed at him, then he jerked his thumb at the sheeted figure. ‘If you can tell me how an old geezer like that can stab himself where I can’t even scratch fleas, I’ll give up trying to be a detective and sell spinach for a living.’

Gently moved over to the oak settle on which the figure lay and turned back the sheet. Huysmann’s body lay on its back, stripped, looking tiny and inhuman. The jaw was dropped and the pointed face with its wisp of silver beard seemed to be snarling in unutterable rage. Impassively he turned it over. At the spot described so picturesquely by Hansom was a neat, small wound, with a vertical bruise extending about an inch in either direction. Gently covered up the body again.

‘Where’s the weapon?’ he asked.

‘We haven’t found it yet.’

Gently quizzed him in mild surprise. ‘You described it in your report,’ he said.

Hansom threw out his hands. ‘I thought we’d got it when I made the report, but apparently we hadn’t. I didn’t know there was a pair. The daughter told me that afterwards.’

‘Where’s the one you have got?’

Hansom made a sign to the uniformed man standing by. He delved into an attaché case and brought out an object wrapped in cotton cloth. Gently unwrapped it. It was a beautifully ornamented throwing knife with a damascened blade and a serpent carved round the handle. It had a guard of a size and shape to have caused the bruise on Huysmann’s back.

‘Does it match the wound?’ Gently asked.

‘Ask the doc,’ returned Hansom.

The heavily jowled man who sat scribbling at a table turned his head. ‘I’ve only probed the wound so far,’ he said, ‘but as far as I can see it’s commensurate with having been caused by this or an identical weapon buried to the full extent of the blade.’

‘What do you make the time of death?’

The heavily jowled man bit his knuckle. ‘Not much later than four o’clock, I’d say.’

‘And that’s just after your Peter Huysmann was heard quarrelling with his papa,’ put in Hansom, with a note of triumph in his voice.

Gently shrugged and walked over to the wall. The room was of the same size as the sitting-room opposite, but differed in having a small outer door at the far side. Gently opened it and looked out. It gave access to a little walled garden with a tiny summer-house. There was another door in the garden wall.

‘That goes to the timber-yard next door,’ said Hansom, who had come over beside him. ‘We’ve been over the garden and the summer-house with a fine-tooth comb and it isn’t there. I’ll have some men in the timber-yard tomorrow.’

‘Is there a lock to that door in the wall?’

‘Nope.’

‘How about this door?’

‘Locked up at night.’

Gently came back in and looked along the wall. There was an ornamental bracket at a height of six feet. ‘Is that where you found the knife?’ he enquired, and on receiving an affirmative, reached up and slid the knife into the bracket. Then he stood there, his hand on the hilt, his eyes wandering dreamily over the room and furnishings. Near at hand, on his right, stood the open safe, a chalked outline slightly towards him representing the position of the body as found. Across the room was the inner door with its transom light. A pierced trefoil window on his left showed part of the summer-house.

He withdrew the knife and handed it back to the constable.

‘What has the mastermind deduced?’ asked Hansom, with a slight sneer.

Gently fumbled for a peppermint cream. ‘Which way did Peter Huysmann leave the house?’ he countered mildly.

‘Through the garden and the timber-yard.’

‘What makes you think that?’

‘If he’d gone out through the front door the maid would have known – the old man had a warning bell fitted to it. It sounds in here and in the kitchen.’

‘An unusual step,’ mused Gently. He turned to the constable. ‘I want you to go to the kitchen,’ he said. ‘I want you to ask the maid if she heard any unusual noise whatever after the quarrel between Peter and his father this afternoon. And please shut all the doors after you. Oh, and Constable – there’s an old chest standing by the stairs in the hall. On your way back you might lift the lid and see what they keep in it.’

The constable saluted and went off on his errand.

‘We’re doing the regular questioning tomorrow,’ said Hansom tartly. Gently didn’t seem to notice. He stood quite still, with a far-away expression in his eyes, his lips moving in a noiseless chant. Then suddenly his mouth opened wide and the silence was split by such a spine-tingling scream that Hansom jumped nearly a foot and the police doctor jerked his notebook on to the floor.

‘What the devil do you think you’re doing!’ exclaimed Hansom wrathfully.

Gently smiled at him complacently. ‘I was being killed,’ he said.

‘Killed!’

‘Stabbed in the back. I think that’s how I’d scream, if I were being stabbed in the back . . .’

Hansom glared at him. ‘You might warn us when you’re going to do that sort of thing!’ he snapped.

‘Forgive me,’ said Gently apologetically.

‘Perhaps you break out that way at the Yard, but in the provinces we’re not used to it.’

Gently shrugged and moved over to watch the two finger-print men at work on the safe. Just then the constable burst in.

‘Ah!’ said Gently. ‘Did the maid hear anything?’

The constable shook his head.

‘How about you – did you hear anything just now?’

‘No sir, but—!’

‘Good. And did you remember to look in the old chest by the stairs?’

The impatient constable lifted to the common gaze something he held shrouded holily in a handkerchief. ‘That’s it, sir!’ he exploded. ‘It was there – right there in the chest!’

And he revealed the bloodied twin of the knife which had hung on the wall.

‘My God!’ exclaimed Hansom.

Gently raised his shoulders modestly. ‘I’m just lucky,’ he murmured, ‘things happen to me. That’s why they put me in the Central Office, to keep me out of mischief . . .’

THE TABLEAU IN the study – constable and knife rampant, inspector passive, corpse couchant – was interrupted by the ringing of a concealed bell, followed by the entry of Superintendent Walker. ‘We’ve lost young Huysmann,’ he said. ‘I’m afraid he’s made a break. I should have had him pulled in for questioning right away.’

Hansom gave the cry of a police inspector who sees his prey reft from him. ‘He can’t be far – he’s probably still in the city.’

‘He went back to the fair after he’d been here,’ continued the superintendent. ‘He had tea with his wife in his caravan and did his stunt at 6.15. He was due to do it again at 6.45. I had men there at 6.35, but he’d disappeared. The last person to see him was the mechanic who looks after the machines.’

‘He was going to face it out,’ struck in Hansom.

‘It looks rather like it, but either his nerve went just then or it went when he saw my men. In either case we’ve lost him for the moment.’

‘His nerve went when he saw the paper,’ said Gently through a peppermint cream.

The superintendent glanced at him sharply. ‘How do you know that?’ he asked.

Gently swallowed and licked his lips. ‘I saw it. I saw him do his stunt. His nerve was certainly intact when he did that.’

‘Then for heaven’s sake why didn’t you grab him?’ snapped Hansom.

Gently smiled at him distantly. ‘If I’d known you wanted him I might have done, though once he got going he was moving faster than I shall ever move again.’

Hansom snarled disgustedly. The superintendent brooded for a moment. ‘I don’t think there’s much doubt left that he’s our man,’ he said. ‘It looks as though we shan’t be needing you after all, Gently. I think we shall be able to pin something on young Huysmann and make it stick.’

‘Gently doesn’t think so,’ broke in Hansom.

‘You’ve come to a different conclusion?’ asked the superintendent.

Gently shrugged and shook his head woodenly from side to side. ‘I don’t know anything yet. I haven’t had time.’

‘He found the knife for us, sir,’ put in the constable defiantly, thrusting it under Walker’s nose. The superintendent took it from him and weighed it in his hand. ‘Obviously a throwing knife,’ he said. ‘We’ve just found out that young Huysmann used to be in a knife-throwing act before he went into the Wall of Death.’

‘That’s one for the book!’ exclaimed Hansom delightedly.

‘All in all, I think we’ve got the makings of a pretty sound case. I’m much obliged to you, Gently, for consenting to help out, but the case has resolved itself pretty simply. I don’t suppose you’ll be sorry to get back to your fishing.’

Gently poised a peppermint cream on the end of his thumb and inspected it sadly. ‘Who was watching Huysmann from the room across the passage this afternoon?’ he enquired, revolving his thumb through a half-circle.

The superintendent stared.

‘You might print the door handle and the back of the chair that stands just inside,’ continued Gently, ‘and photograph the marks left on the carpet. Then again,’ he turned his thumb back with slow care, ‘you might wonder to yourself how the knife came to be in the chest in the hall. I can’t help you in the slightest. I’m still wondering myself . . .’

‘Well, I’m not!’ barked Hansom. ‘It’s where young Huysmann hid it.’

‘Why?’ murmured Gently, ‘why did he remove the knife at all? Why should he bother when the knife couldn’t be traced to him in any way? And if he did, why did he take it into the hall to hide it? Why didn’t he take it away with him?’

Hansom gaped at him with his mouth open. The superintendent chipped in: ‘Those are interesting points, Gently, and since you’ve made them we shall certainly follow them up. But I don’t think they affect the main issue very materially. We need not complicate a matter when a simple answer is to hand. As it rests, there is no suspicion except in one direction and the suspicion there is very strong. It is our duty to show how strong and to produce young Huysmann to answer it. I do not think it is our duty, or yours, to hunt out side issues that may weaken or confuse our case.’

Gently made the suspicion of a bow and flipped the peppermint cream from his thumb to his mouth. Hansom sneered. The superintendent turned to the constable. ‘Fetch the men in with the stretcher,’ he said, and when the constable had departed, ‘Trencham is going to meet me at the fairground with a search warrant. You’d better come along, Hansom. I’m going to search young Huysmann’s caravan.’

Gently said: ‘I’m still interested in this case.’

The superintendent paused. He was not too sure of his position. While the matter was doubtful, the sudden appearance of Gently on the scene had seemed providential and he had gratefully enlisted the Chief Inspector’s aid, but now that things were straightening out he began to regret it. There seemed to be nothing here that his own men couldn’t handle. It was only a matter of time before young Huysmann was picked up: the superintendent was positive in his own mind that he was the man. And the honour and glory of securing a murder conviction was not to be lightly tossed away.

At the same time, he had brought Gently into it, and though the official channels had not been used, he was not sure if he had the power to dismiss him out of hand. Neither was he sure if it was policy.

‘Stop in if you like,’ he said, ‘it’s up to you.’

Gently nodded. ‘It’s unofficial. I won’t claim pay for it.’

‘Will you come along with us to the fairground?’

Gently pursed his lips. ‘No,’ he said, ‘it’s Saturday night. I feel tired. I may even go to the pictures . . .’

The constable left in charge was the constable who had found the knife. Gently, who had lingered to see his finger-printing done, called him aside. ‘You were present at the preliminary questioning?’ he asked.

‘Yes, sir. I came down with Inspector Hansom, sir.’

‘Which cinema did Miss Huysmann go to?’

‘To the Carlton, sir.’

‘Ah,’ said Gently.

The constable regarded him with shining eyes. ‘You’ll excuse me, sir, but I would like to know how you knew where the knife was,’ he said.

Gently smiled at him comfortably. ‘I just guessed, that’s all.’

‘But you guessed right, sir, first go.’

‘That was just my luck. We have to be lucky, to be detectives.’

‘Then it wasn’t done by – deduction, sir?’

Gently’s smile broadened and he felt for his bag of peppermint creams. ‘Have one,’ he said. ‘What’s your name?’

‘Thank you, sir. It’s Letts.’

‘Well, Letts, my first guess was that there’d been some post-mortem monkeying because the knife was missing and there was no reason why it should have been. My second guess was that the party who was watching from the other room this afternoon was the party concerned.’

‘How did you know the

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...